A poignant moment in Australian rugby occurred on 15 August 1914 when the touring All Blacks side was playing a Metropolitan XV at the old Sydney Sports Ground. During the match, this message was placed on the scoreboard: WAR DECLARED.

It has been estimated that 5,000 Australian rugby players went on active war service between 1914 and 1918. This total represented about 98 percent of the playing numbers in the game at the time, outside of the schools.

The club championships in Sydney and Brisbane were cancelled. The Queensland Rugby Union went out of existence. It was finally revived in 1929.

Australia, the other ‘settler colonies’ of New Zealand and South Africa, and rugby’s home unions paid a high price for rugby being the Empire’s war game. In all probability, no major sport suffered as many casualties in World War I of players, former players and officials as rugby.

From its inception, there was a missionary element built into the DNA of rugby. The values of ‘muscular Christianity’, the founding doctrine of Rugby School’s famous headmaster, Dr Arnold, were spread by old boys, along with the school’s distinctive game wherever they went in the colonies.

The rugby game was also picked up by the British armed services as a splendid exercise in the manly virtues that would be useful in wars.

And not only by the armed services. Baron Pierre de Coubertin, the founder of the modern Olympics and the man responsible for rugby being an Olympic sport up to the 1920s, saw rugby as a game that could toughen up French youth in the 1890s for the inevitable battle to the death with a rampant, expanding Germany.

Rugby is a war game, it is not war itself. But it was the war game aspect of it that attracted the attention of school teachers and Empire loyalists in the colonies.

The game tested courage, resilience and attitude, all qualities useful qualities for soldiers to have in battle. It was a combative sport requiring discipline, fitness, quick thinking and a strategic element that could easily translate into battle field tactics.

The metaphors of rugby give a deep clue to its war game connotations. Players kick bombs and torpedo kicks. They fire off bullet passes. Halfbacks snipe down the flanks. The ball is killed in rucks. Teams play for position and territory. Defenders make big hits. Props are built like tanks. Swift backs launch Panzer attacks.

A strong offence is met with a passionate defence. There are forward drives and aerial attacks…

The 1916 NSWRU annual report listed 115 former players who had died in the war. At the end of the Gallipoli campaign, seven Wallabies were buried on the Dardenelles peninsula.

The Referee, a popular sporting magazine of the day, published a series of moving letters from rugby players relating their experiences at Gallipoli. The letters make haunting reading.

The players write about their yearning for the simple pleasures of home life, their loved ones, deeds of heroism and the hope that they would experience again the simple, exuberant joy of chasing a skittish rugby ball on a field a with their mates.

Here is Clarrie Wallach, a Wallaby against the All Blacks in 1913: ‘We arrived at Hellopolis about three weeks ago. We have been in pretty solid work but expect the real stuff next week.’

‘All the rugby union men are well here, from the Major down to the privates. Twit Tasker told me how Harold George died a death of death – a hero’s – never beaten until the final whistle.’

William ‘Twit’ Tasker himself died of wounds on the Western Front in France in 1918. The Major was Major James MacManamey, a leading NSW official. He died a weeks after Wallach’s letter was written. Clarrie Wallach, too, was killed at Gallipoli.

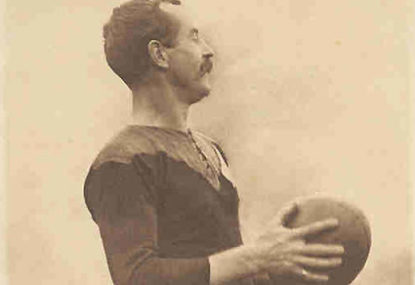

Tom Richards, one of the greatest loose forwards in the history of rugby, was a member of the 1908 Wallabies when they won Australia’s first Olympic gold medal for a team sport, rugby, at the London Olympics. He was one of the first ANZACs to land at Gallipoli and one of the last to leave.

He later served in France where he was awarded a Military Cross. He survived a gas attack and a bomb blast that damaged his back and shoulders. He never played rugby after 1918.

In June/July of this year, the Wallabies and the British and Irish Lions will play a three-Test series for the Tom Richards Cup.

In all, nine Wallabies died during World War I. Scotland lost 30 international players: England 27: France 23: New Zealand 12: Wales 11: Ireland nine: Wales three: South Africa four

David Bedell-Sivright, considered one of the greatest Scottish players of all time, was one of those killed.

Ronnie Poulton-Palmer, England’s greatest centre who scored four tries in his last Test against France, was another star who was killed, aged 26, in his rugby prime.

Dave Gallaher, the captain of the 1905 All Blacks, and the founding father of the All Blacks system and ethic of playing rugby, was killed on Western Front in 1917.

The New Zealand sports journalist Lyn McConnell has researched and written about what is, in my view, one of the most haunting of all rugby stories. It concerns Gallaher and the vice-captain of the 1905 All Blacks, Billy Stead, a Maori five-eighth who was noted for his acute rugby brain and his expertise in devising tactics.

The 1905 All Blacks are credited with inventing the modern game of rugby. They pioneered specific positions in the forwards. They had lineout drills and calls. They created backline moves on blackboards on their train between matches and then put them into practice.

The essence of their thinking was that their game should be more rugby (a ball-in-hand running game) than football (a kicking game). The team’s ensemble play was so original that British writers called the team ‘the all backs’ and the All Blacks.

After the tour, where the only match lost was a controversial defeat to Wales, Gallaher and Stead wrote a book about the tour and their their thinking of rugby, ‘The New Zealand System of Playing Rugby.’ The great Lions coach Carwyn James called it the finest book ever written about the game.

Stead was a boot-maker who lived and worked in the deep south town in New Zealand of Invercargill. In his shop, behind his working bench, he had a large photo behind glass of the 1905 All Blacks side.

In early October 1917, Stead was behind his bench. A horse carriage was driven past the shop. A stone flew up from the hoof of the horse and went through the open door and struck the photo. The splinter in the glass was on Gallaher’s heart.

Later on, Stead found out that the stone struck Gallaher’s photo in Invercargill at the same time that he was shot on the Western Front.

Lest we forget …