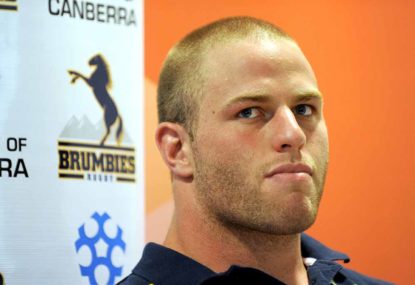

For the princely sum of a long black coffee, I spent an hour late last week talking scrums with former Waratahs and Brumbies prop, and one-Test Wallaby, Dan Palmer.

And it was exactly the sort of chat I was hoping for, complete with a couple of forks packing down against a couple of knives incapable of packing straight.

Now retired from playing – very happily so, as it happens – Palmer balances full-time study with the scrum coaching role at the Brumbies. For the NRC, this has expanded to include the Uni of Canberra Vikings lineout set piece and maul. On current evidence, he’s making a very smooth transition into coaching.

More Rugby World Cup:

» LORD: No surprises in Wallabies team

» Rugby World Cup fixtures

» Rugby World Cup results

» Rugby World Cup highlights

» Rugby World Cup news and opinion

It’s not often you get this sort of time and access to talk technicalities with professional coaches, and certainly not to bust things down to such an elementary level. But ‘Palms’ was happy to talk, and I was happy to listen; though my sideline vantage point has certainly allowed me to see and understand more about what goes on scrums these days, it’s an inescapable fact that I never packed down in a rugby scrum.

I wanted to start with a really obvious question, but kind of knew there wouldn’t be one simple answer.

Why do scrums typically collapse?

“Well, you can collapse a scrum for all kind of reasons,” Palmer begins the lesson. “It could be technical deficiency; someone’s technically not good enough. It could be a strength deficiency; they’re not strong enough. It could be tactical; there are times where it might be beneficial to collapse a scrum. We (the Brumbies and Vikings) don’t do that, obviously,” he says, with a grin.

“I guess there’s any number of reasons, but it all comes down to force and force transfer, and whether you’re in the right position technically to transfer and absorb the force, whether you’re strong enough to transfer and absorb force, and tactically, whether you’re willing to; you might want to collapse a scrum.

“There’s a whole range of reasons why scrums collapse, and there’s no simple answer. It’s never as clear cut as one of those things, and it could be a combination of any number of things. It might just be the fact that the timing of things is just not quite right for that particular scrum.

“And it might just be that we like packing scrums and want to pack more of them!”

So then, tell me about that moment in the middle of a scrum, when you have everything right, and the timing’s perfect, and you win the initial hit, and then you get pinged even though the opposition went down?

“That’s incredibly frustrating, and it’s something that’s always going to be a constant battle, because you can never truly know with the ref standing there, and I get that. But if you’re going to get penalised for being dominant, then there is no point trying to get your scrum better and to become dominant and to get that advantage, because you might as well be the weaker scrum and get all the penalties.

“Which has been a frustration this year – not in the NRC – because I’ve felt like we’ve earned dominance, but we’ve penalised off the park for it on occasion. It’s bizarre to me because getting scrum dominance is a f—ing hard thing to do, and it’s something that you work really hard at in the pre-season and during the season; you spend a lot of time on it. And to then earn that dominance and then get penalised for it is very, very frustrating.

“I understand it’s a really difficult area to police, but we definitely do have to upskill everyone involved, including the refs.”

So then, how knowledgeable is your average Australian referee, let alone Super Rugby referee, let alone Rugby World Cup referee?

“How many referees look like ex-tightheads to you? This is a fundamental problem; the people who go into refereeing are generally… well, the closest they’ve got to a scrum is standing next to it occasionally. And that’s perfectly fine; it doesn’t bother me at all, but I think we should be putting measures in place to upskill. And that is beginning to happen, but it’s a long process. To learn how to [pack scrums] is a long process, so to look at it externally, having never done it, and to try and work it out is going to take time.”

“I might be over-simplifying it, but in a way, I think the French have it right. They will not look at technical things too much, and they will just reward dominance. So if you’re dominant, it’s probably going to go in your favour. You might be dominant for slightly illegal reasons, but who cares, that’s the art, and you’ve got to get better at that.

“They’ve depowered the hit, so what you want to do is get from your set-up position to your engage position as efficiently as possible. But completely dominating that space – and we’re only talking about maybe six inches – is probably going to work against you in that they’re becoming more and more likely to issue a free kick for pushing off the mark, or instability at the point of contact.

“So I think the really good scrums now are getting really efficient at getting from their set-up position to their engage position in a really controlled manner. So they really control that space at the point of contact and they have a big emphasis on the timing of the shove after that, and to try and generate momentum without the big hit.

“And after that, my thought is you have to side with dominance. Because if you’re protecting the weaker team, then what’s the point? What’s the point of being dominant? What’s the point of spending time to get a good scrum and putting in the hours analysing your game and their game to get better? There’s no point. Why not just be the weaker scrum and get all the penalties?”

It’s at this point I recall my cricket playing days (not that long ago, thank you), and how the top umpires – or the ones who wanted to improve – would drop into a training session, and just umpire in the nets. It was as good for the umpires as it was for players, and I know some Test umpires still do it now. How many rugby referees would benefit from coming to a scrum session and doing the same?

“It doesn’t happen too much, though some of them do go out of their way to come in and work with us a bit,” Palmer said. “I think that could be part of their learning process, I wouldn’t have any problem with that. They could most certainly come in to one of our sessions.”

From here, we went into the really technical parts of the fascinating conversation, with the good-guy Forks aligning straight and getting their timing perfect on the ‘set’ call, only to encounter the dastardly Knives pack, who were well versed on the dark arts.

I suspect the explanations were coming direct from the Brumbies and Vikings manual for young props, too, because all the explanations were very clear and very reasoned, and very much off the record. “Don’t write this” became as commonplace in the conversation as the arrows indicating where the force was going in each demonstration, as the Forks tried to get themselves into the scrum contest and achieve parity.

One of the big lessons I took out of all this was the positioning of both prop’s feet on the set-up, and how on the point of contact, the hips follow the feet. The loosehead and tighthead will lead with different feet, so as to direct the force on the right angle. The same applies to the locks and flankers behind each prop.

As the Forks got better during the lesson, they were able to get their timing right, and by packing dead square as a concerted pack, were able to shear off the Knives’ loosehead, and effectively create a dominant eight-on-four situation. That, Palmer said, is always the goal; to win the contact, and spilt the opposition scrum with your dominance.

It’s been really interesting to watch scrums over the weekend, and to now have a better understanding of why some teams are getting towelled up in the scrums, and even how some international props don’t use this relatively obvious technique at set-up.

Palmer told me what changes he brought into the Brumbies pack when he first arrived and essentially became the playing scrum coach in 2012, including who leads the initial engagement, who makes the call on when to prepare for and when to unleash the second shove, and indeed, what the call is. From what I’ve read and understand about the Argentinean ‘Bajada’, Palmer’s method is similar but different.

Eventually, the Forks did become dominant, and learned to deal with most things the Knives threw at them. Unfortunately though, the Knives loosehead was taken away with the empty coffee cups, and we had to go uncontested. Turns out the Knives were in clear breach of Law 3.5, with no suitably trained replacements appearing.

Once back on the record, I was interested to hear Palmer’s thoughts on the Wallabies’ scrum improvements under Mario Ledesma.

“The Wallabies scrum has been a s**tfight for a long time now, that’s no secret. From what I can see, Ledesma is making really good inroads. I’ve not spoken with him directly about this stuff yet, but everything he’s focussing on makes perfect sense. I think we can see the Wallabies trending in the right direction.

“We’re certainly nowhere near the finished product, but we’re trending in the right direction and I think he’s doing an outstanding job.

“We saw the Waratahs under him improve significantly this season, and he’s a very well respected hooker from a very well respected club in Europe (Clermont Auvergne), and an Argentinean hooker who went to four World Cups.”

We discussed my views from this time last year, where I observed that despite the front row getting all the criticism, the back-five scrum engagement was essentially counter-productive. There were anything but a concerted pack.

“At the most basic level, you just want eight people doing the same thing at the same time; that’s what scrummaging is,” Palmer said. “It’s about getting everyone on the same page, and that’s how you get results. We just haven’t had the right focuses around the scrum for a long time now, and I think Mario’s refocussing the view onto what’s important.”

Of the Rugby World Cup teams, Palmer said that both Wales and England would present challenges at scrum time, though I’d love to have timed our chat for after when the England pack was often in hasty retreat against Fiji.

“Georgia will have a strong scrum, as always. They’ll upset a lot of scrums. A lot of those guys play in France, and they’re really established scrummagers who nobody here really knows about, but as scrummagers, they’ve got pretty big names over there.

“New Zealand are interesting. They’ve always had an efficient scrum that gets the job done, but they were never a team that you’d have to worry about really hammering it home at scrum time. They’re not going to just walk scrums up the field or take you for penalties, and that’s not to take anything away from their pack; it’s just not the way they play.

“They’ve got an extremely good forward pack, they’re all good scrummagers, and they’re very efficient, but it’s not in their game plan to take it to you there. They won’t be as big a danger to us as some of the northern hemisphere teams will be, and the Argentineans as well.

“I think we saw it in the Bledisloes, that we’ve improved to the point that I can’t really see the Kiwis bothering us in that area,” he said.

Perceptions of said improvements, however, are not as quickly fixed. “One good game is never going to be enough. To change a perception of the Wallabies pack is going to take a consistent effort over a long period of time, and so it should. It’s going to take longer than a year, but if we keep tracking the way we are, then we’re well on the way to doing that.”

What about any international scrums that are perhaps a bit overrated?

“I’m sure there are… I’ll give you an answer to that after the World Cup.”

And that’s another coffee I’m already looking forward to.