WATCH; IPL bowler fuming after getting robbed of near-certain wicket by... Spider-Cam

Harshal Patel was not a happy man!

“Whenever I get married, it will be a Bengali wedding. If I won’t have a Bengali wedding, my mother won’t come. She has warned me. So, I am going to have a Bengali wedding for sure.” – Bipasha Basu.

The invitation was irresistible. Would we like to attend the wedding of Judy’s niece in Kolkata to a Bengali man she met and fell in love with when they were studying at Oxford University?

The wedding ceremony would be held over four days at a special resort designed to cater for Bengali weddings.

Would we ever.

More cricket:

» Paine and Hastings in my Australian World T20 squad

» BBL Weekly: The crystal ball edition

» A completely biased and subjective T20 World Cup squad

» Has the commercialisation of sport gone too far?

» Steve Smith’s Border-esque rebuild

There was a family aspect about the wedding, with the Australian family members able to get together again with those members of the extended family who lived in the UK.

And there was, for want of a better phrase, the ‘Marigold Hotel’ expectation for those of us of a certain age. We were eager to indulge in several days of frantic buying of special garments to be worn at the different events.

Many of the women were expected to wear the sari or a Bengali salwar khamiz with its convenient, given the amount of food expected to be consumed, drawstring pants.

There was the promise, too, of high intensity music, ululating and dancing for hours on end.

Among the colourful ceremonies set out for the wedding were rituals such as the mock forced-feeding of the bride by her putative mother-in-law, a “bou bhat” reception involving around 300 to 400 people bringing presents and blessing for the couple.

Also, the “Ashir-bad” where the bride’s relatives (us) bless the bride, a “Gail holud” ceremony as tumeric is placed on the bride and groom’s face for good health, a “tatoo”, gift-giving from the groom’s side to the bride’s side, and “bashi-biye” when the process is reversed.

And finally, after four days into the wedding reception, there was going to be an evening play organised by some of the groom’s relatives.

There is a growing discussion in India about the significance of the wedding ceremonies and what the changes to them mean as a sign for a new, improved and less hidebound India.

The Times of India ran an article before Christmas by Santosh Desai headed: “The choreography of excess”.

The principle idea in the article is that weddings in India have changed from family affairs with “set conventions” involving couples who did not understand was was happening. Now the couple rather than the family runs the show. And the couple get to “invent” their meaning of the wedding as a “private fantasy”.

“The wedding is now an event to be conceived and managed as a piece of entertainment … will it photograph well and outshine other efforts mounted by peers.”

I must say this was true of our Bengali wedding. The couple organised the occasion and paid for most of it.

When I read this article and its intricate and well-organised argument I thought immediately that this is what the Indians have done with cricket. They have taken an ancient and timeless game and jazzed it up into a show with their IPL tournament.

IPL cricket has become a sporting Bollywood. Cricket and weddings in India, as Desai argues, become “a public screening of private fantasy, with every element amplified … with our biggest fear being to lead a life that does not need to be obsessively photographed”.

For me, too, in coming to India to experience a Bengali wedding there was the additional chance to indulge myself, as someone brought up as a young reader on the Rudyard Kipling stories, to immerse myself in Indian life, its newspapers, its culture in Delhi and Kolkata and how this all tied up with the Indian love and practice of cricket, a interest of mine since I was a youngster.

This passion started when I saw photos of Don Bradman pushing an innocuous, round-arm delivery from the Indian skipper Lala Armanath in an Australia-India Test and racing towards the bowler’s end like a greyhound from the traps to complete his 100th century in first-class cricket.

I admired a methodical opening bat and cunning left-arm slow bowler in that same 1946-47 Indian side in Australia, Vinoo Mankad. I based my nascent cricket talents on emulating Mankad, as a putative opening batsman and spin bowler.

Much later in my career I tried to ‘Mankad’ an opposing batsman out, reveling in imitation being the sincerest form of flattery.

During this time, too, the great John Reid told me and a group of other youngsters about his experiences in playing cricket in India: the massive Eden Garden’s complex, the intense heat and difficulties of avoiding Delhi belly and the virtual magical skills, batting and bowling, of the Indian greats.

Mankad had scored the then fastest double century in Test cricket against New Zealand. And Subhas Gupte, a leg-spinner in the Clarrie Grimmett mould, Reid told us had two different wrong’uns, one you could pick and one you couldn’t pick. For me this was the cricketing equivalent of the Indian rope trick.

To give a context to my learning about Indian cricket and what made it work and not work I brought with me on the wedding trip one of the finest books ever written about cricket, “A Corner of a Foreign Field: The Indian History of a British Sport” which was written by Ramachandra Guha.

The book, which is scholarly and engrossing, is described by Guha as “not so much a history of Indian cricket as a history of India told through cricket and cricketers”.

The first great Indian cricketer, according to Guha’s account, was a left-arm spinner Palwankar Baloo, an Untouchable.

A description of Baloo bowling at his prime reads like an account of Bishan Bedi’s meticulous, fluid and lethal bowling style: “Baloo was a fine left-hand bowler who possesses marvellous stamina. Breaks from both sides. Has the easiest of deliveries. Seldom tires. Can bowl all day long. Keeps an excellent length. Never sends down a loose delivery.”

On a tour of England in 1911 when an Indian side played the major county sides, Baloo took 114 wickets at 19 runs a wicket, a statistic that would have been much more impressive if ‘support in the field’ had been of the same standard as the bowling.

According to Guha there are several fissures (potential and actual in differing times) in the facade of India cricket.

The first involves caste. Baloo was never given the captaincy of any of the sides he played for because of his caste, according to Gupa. There have been few, if any, other Untouchables have been selected to play for Indian sides. Later in his life Baloo went into politics and became an ally of Matahma Gandhi to win some rights for the Untouchables.

One of the struggles that has often convulsed India cricket, aside from caste considerations, has been how to accommodate the diversity and antagonism of the various racial groups in India. Between 1971 and 1983, according to Gupa, this internal diversity in India sides was made easier by the success of these teams.

The 1971 side had Hindus and Muslims as well as a Parsi and a Sikh. In 1983, in a side that won the World Cup, there was no Parsi in the side but the three other faiths were represented, and there was a Christian as well.

The accomodation between Hindus and Muslims in cricket, though, has become frayed because of the Kashmir Dispute. With this dispute, the relationship between India and Pakistan has collapsed. There are repercussions for Indian cricket involved in all of this.

Gupa sums up this situation: “In a political beauty contest between India and Pakistan, India would win hands down .. But the gap between theory and practice is growing, especially when the Bharitiya Janata Party (BJP) is in power, India sometimes can look like a mirror image of Pakistan. There is increasing hostility to minority communities, especially the Muslims.”

That was written in 2003. Since then the hostility has intensified, with the increase of terrorist attacks within India.

One of the impressive aspects of Indian politics is the robust discussion of it in the major Indian newspapers. So I was interested in Gupa’s article in The Times of India while I was there (December, 2015) about the “fading magic” of the Nehru-Gandhi control of the Congress Party and the BJP’s attacks on Rahul Gandhi as the “spoilt child” of Indian politics who could “ruin” the party and the nation if he is allowed to stay in control of the party.

The presumption of the article is that the Hindu-first BJP will benefit from the dysfunctionality inside the Congress Party. Gupa has described the BJP as as a “brain-dead” party. And carrying this argument further, he argued this shallowness of thinking within the BJP could lead to a further alienation of Muslims in Indian life and, even more likely, to an intensification of the corruption of the already squalid world of Indian politics and cricket.

An example of this corruption in politics seeping through into the world of cricket is a dispute that is raging over the funding and kick-backs concerning a new cricket stadium in Delhi.

The federal finance minister, Arun Jaitley, a BJP heavyweight, was the president of the Delhi and District Cricket Assocation (DDCA) between 2004 and 2013 when the stadium was being funded and built.

No public expenditure was spent on the stadium’s construction. The political row is over the way private funds were raised to achieve this. Where did the huge sum of money needed for the construction come from? Who benefited from the way the money was raised?

According to the opposition there was massive graft paid out to the BJP over the deal.

In The Australian (January 2, 2016), Gideon Haigh has a devastating article on accusations of corruption in the workings of the Board of Control for Cricket in India, “the de facto seat of power in world cricket”. A current matter under investigation, according to Haigh, concerns allegations of corruption within the Indian Premier League franchises, the Chennai Super Kings and the Rajasthan Royals.

Haigh notes that the BCCI’s “ambitious, young” secretary is Anurag Thakur, the “scion of a BJP dynasty”.

Haigh further notes that the investigation is centering on the DDCA and its president from 1999 to 2013, the BJP powerbroker, Arun Jaitley: “For much of this period, the DDCA was a byword for corruption and nepotism, colloquially known as the ‘Delhi Daddies and Crooks Assocation,’ deflecting multiple efforts at reform …

“Jaitley moved onward and forward: as BJP’s leader Narendra Modi’s finance minister, he is regarded by some as the second most powerful man in India. The DDCA has since more or less collapsed, mysteriously denuded of funds. India’s recent Delhi Test was overseen by a retired judge, Mukul Mudgal … It earned a profit for the first time since he early 1980s. Just fancy that!”

Haigh’s point is telling. India’s endemic political corruption that was created by the Congress Party and now is being maintained and extended by the ruling BJP throughout Indian cricket.

This is at the time when India bankrolls world cricket. The challenge to this political/cricket corruption has massive implications throughout the cricket world, Haigh argues: “A system (the corrupt Indian system) that has enriched so many will not pass without a struggle: for many the current system works just fine. But aware of it or not, cricket around the world has a great deal invested in the outcome.”

The success of Mukul Mudgal in running a profitable and enjoyable Test in Delhi was not lost on political analysts during the time I was in India.

Here is Pradeep Magazine, a professional cricket writer (with a great name for a writer) giving the big picture: “The Delhi Test was a revelation and it had to do with the numbers at the ground. The stadium, an ugly mass of concrete, was brought to life by a throbbing, lively crowd … tickets were easily available and sold at much cheaper rates than the organisers have in the past … Justice Mudgal has set a new template for how to get crowds into Test matches.”

This success comes at a time when Indian cricket is facing its biggest challenge from another sport since independence when the BJP tried to ban cricket as the “English game” and wanted to promote hockey as an authentic Indian sport.

Cricket easily beat off hockey as the national sport. But now more than 60 years after independence, cricket is being challenged by football, an authentic world sport.

An article that took my eye on this matter was in The Hindustan Times, a supportive Delhi daily newspaper of the BJP: “From monopoly to jostling for space” by Sanijeeve K Samyal.

The article started with a question: who has bagged the most lucrative advertising deal among sportspersons in India?

Answer: Lionel Messi.

This signing by Tata Motors is a “big shift”. It signifies world football challenging the primacy of cricket in India.

“Mumbai, the biggest hub of Indian cricket,” the article points out, “is feeling the shift with college coach Sharad Rumde says from 60 to 70 players coming for selection, the number of down to 17-18.”

Rahul Dravid, in his MAK Pataudi Memorial Lecture, noted: “The generation when you could say that every Indian baby is born with a cricket bat in his hand is well behind us … cricket is not our first game anymore.”

The article points out that a leading equipment manufacturer revealed that in the last four to five years the sales of cricket equipment has gone down compared to footballs.

A major cause for this falling off of sales (but not of interest just yet) is that the Indian middle class has become disillusioned with the corruption within Indian cricket. “The scandals have taken the sheen off the sport.”

I must say that in my three weeks in India I did not see many kids playing cricket on vacant lots or on the streets. But I did see the kids playing football, with all sorts of objects as the ball.

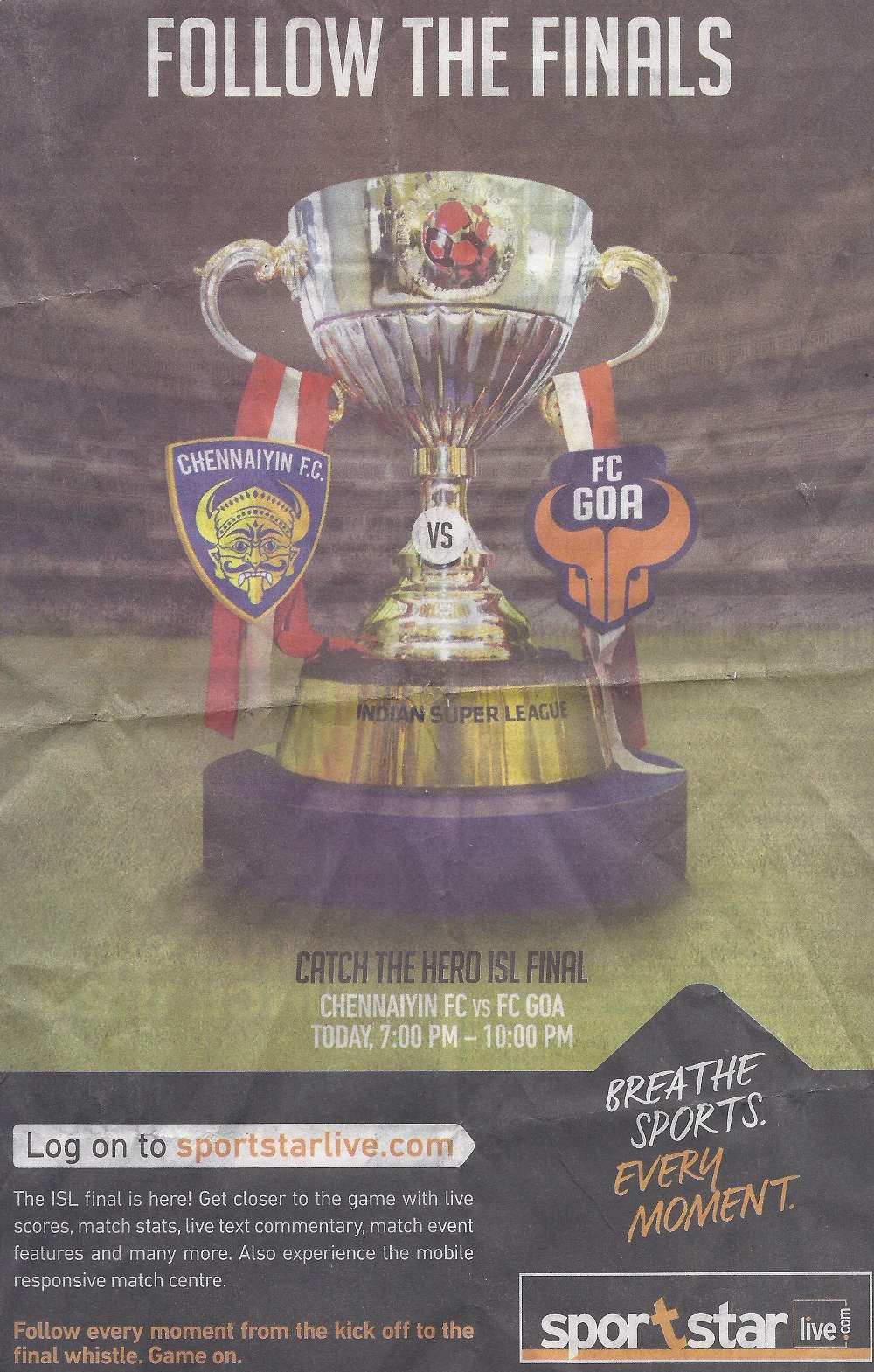

The final of the Indian Super League (ISL) football competition got massive exposure on television and in the newspapers with Chennaiyin FC defeating FC Goa in front of a full house at Fatorda.

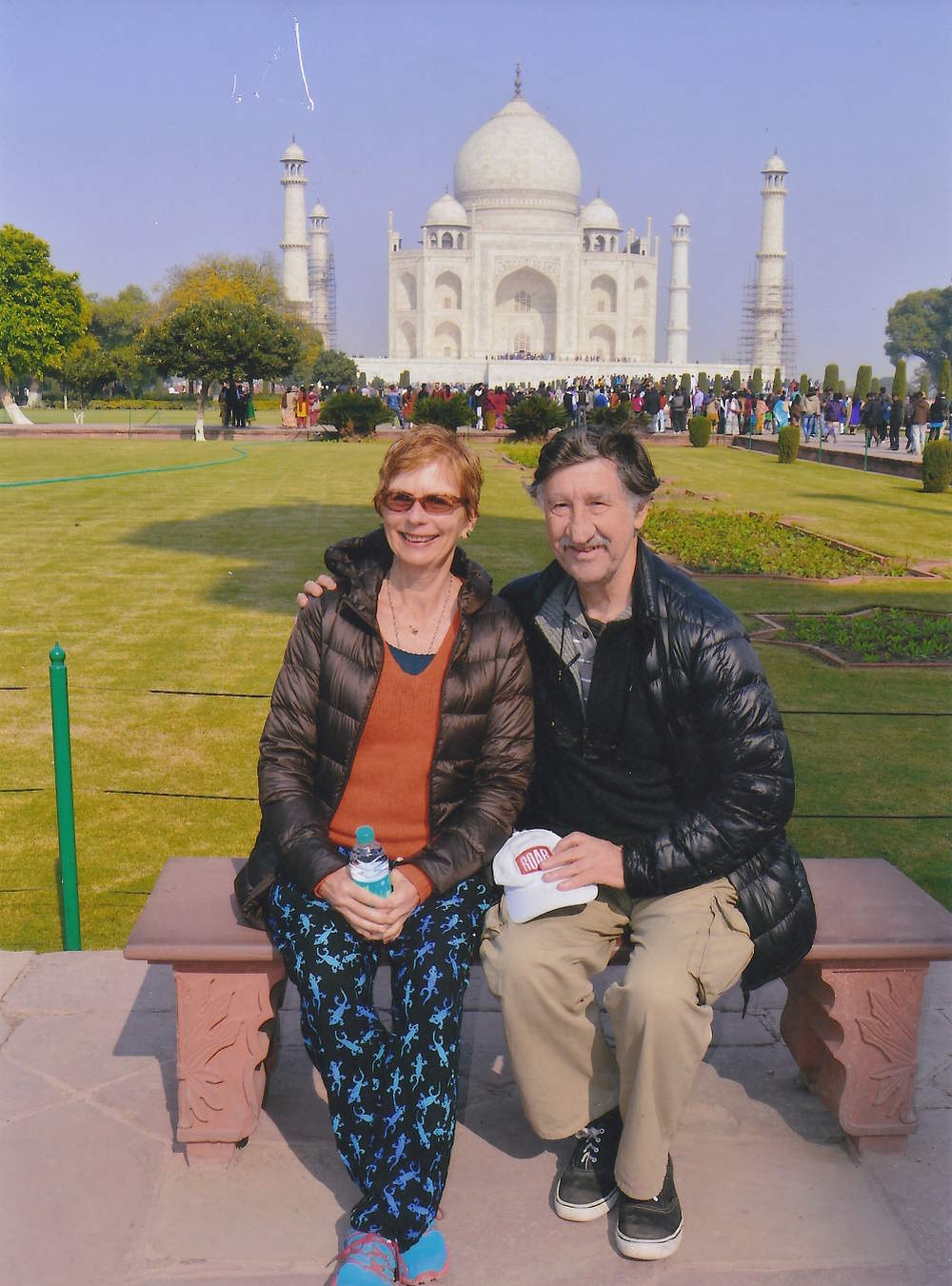

The highlight of any trip to India must be the journey to Agra to see the Taj Mahal.

We did this on a day when pollution and fog made the three to four-hour trip from Delhi a journey into an endless mist. And then, as suddenly as we were engulfed in the mist, we unexpectedly drove out of it near Agra.

It was at the Taj Mahal that I realised and hopefully began to understand something of the Muslim influence on Indian politics, life and culture, including cricket. All those Nawabs of Pataudi, for instance, were Muslims. As was our guide, a charming Mr Ahmed, who explained that the only day of the week the Taj Mahal is closed is on Fridays where an annex serves as a mosque for Friday prayers.

Mr Ahmed took us to a portal of a fort facing the Taj Mahal. He revealed a remarkable trick.

When you moved towards the portal, the Taj Mahal seemed to move away from us. But when you looked at the Taj Mahal as you backed away from the portal, the beautiful iconic structure seemed to be moving towards us.

With that image in our mind, who knows what is reality in India about anything, especially its obsession with cricket and the growing passion for football?