Craig McDermott, Chris Cairns, Adam Hollioake, Wally Hammond, Brian Statham and Tony Lock.

It would be an extremely difficult question for the best quiz buff to answer, if asked for a common thread that links these cricketers of yore.

For the answer is to be found well beyond the 22 yards and indeed the 90-yard boundary lines at the MCG or the Eden Gardens. The common thread that exists here is that all of the above fell into severe, and in certain cases, debilitating and life-threatening financial difficulties once their playing days were over.

The days of IPL, Big Bash and lucrative cricket contracts from Cricket Australia, ECB and BCCI were in the distant future. The likes of Dennis Lillee leading the fight for better pay with the ACB via Kerry Packer’s WSC were years away when Wally Hammond, Brian Statham and Tony Lock hung up their proverbial boots.

Brian Statham was one of England’s great fast bowlers, and formed a fearsome partnership with Fred Trueman. Statham lived in poverty for much of the last 20 years of his life and died of Leukaemia in 2000.

Trueman got him some relief in the 1980s by organising a couple of benefit dinners. Tony Lock, the great English spinner lived in Australia after retirement. Twice accused of sexual abuse, and cleared both times, Lock lost all his savings in legal fees, lost his wife to stress and finally died in Perth aged 65. He was a broken man, spiritually and financially.

Wally Hammond lived a life of extravagance in his playing days, but moving to South Africa after retirement, and two marriages and three children later, died financially broke in 1965. The cricketing world led by Don Bradman raised a memorial fund for him.

The next generation of cricketers fared a little better, but had their share of financial woes. Adam Hollioake and Craig McDermott both went into the property business post retirement in Australia and both had their respective companies going bankrupt post the property meltdown caused by the Global Financial Crisis of 2008.

They have since taken different roads to recovery. Hollioake took up Mixed Martial Arts to earn his living, and McDermott took up a job as a bowling coach at the Centre for Excellence and eventually coached Australia’s bowlers.

Chris Cairns’ story is even more remarkable. In 2010, he was working as a diamond merchant in Dubai, post retirement. In 2012, he won a lot of money in libel claims against the ex Chairman of IPL, Lalit Modi. However it all went downhill thereafter. He was accused of match fixing in 2013, then charged with perjury in England in 2014, and by the time he was acquitted by a court in 2015, he was cleaning bus shelters to make ends meet.

However, it’s not only Cricket that has these stories. Remarkably, in the arena of American sports, which are by far the best paying sports in the world, as per Sports Illustrated, 78 per cent of National Football League (NFL) and 60 per cent of National Basketball Association (NBA) players go bankrupt or are under financial stress in just two years and five years, respectively, after their retirement.

Football players don’t fare much better either despite the exorbitant pay packets at the world’s various leagues, and neither do boxers or tennis players.

Antoine Walker earned US$108 million during his NBA career, and filed for bankruptcy in 2010, two years after retirement. Michael Vick signed a $130 million contract with the Atlanta Falcons for ten years and was one of the highest paid players in 2004, but by 2008 had declared bankruptcy.

Kenny Anderson made US$63 million in his career, but filed for bankruptcy in 2005. Keith Gillespie, the former Manchester United player declared bankruptcy in 2010, admitting he had squandered almost US$11 million.

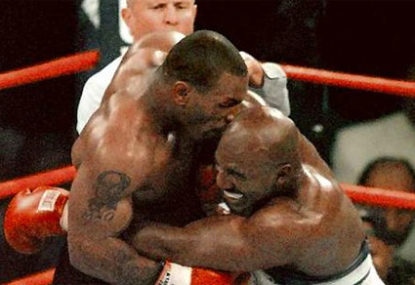

Bjorn Borg won 11 Grand Slam titles, was one of the most successful tennis players ever and tottered on the brink of bankruptcy. Most famous of them all was Mike Tyson. With earnings of over US$400 million in his career, Tyson filed for bankruptcy in 2003.

So is there a common thread running through these stories? What causes otherwise hugely successful men in their respective fields, to fall apart financially once they leave the sport? Is it greed, is it lack of awareness, is it a lack of exposure to the world outside sport, or is it something else altogether?

Something common to every case of financial trouble for sportspersons is the fact that most of them have no idea what to do outside their sports. Their minds are totally hard wired for training and practicing and being the best at what they do.

The fact that their life as they know it ends at about 35 and they have over 40 years to live thereafter, is not something they think about while they are heading to the peak of their prowess. As a result, they are grossly unprepared for what follows.

So education is very important and the NCAA in the U.S. recognises that and does what it can. Universities like Notre Dame, Duke, North Carolina and Boston College will not allow sportspersons to play, no matter how damaging it is for the University, if they haven’t met certain GPA.

Unfortunately, not all colleges even in the NCAA are this strict, for the pressure to win at any cost can be too great. For Indian cricketers and sportspersons, education has always culturally been put above sporting ability by parents and educators alike.

Rahul Dravid, Sourav Ganguly, V.V.S. Laxman all had college degrees before they played for India, and Anil Kumble and Javagal Srinath were engineers by training. Hence most Indian cricketers have been able to earn a normal living after their sporting days, even before the advent of IPL and lucrative TV commentary contracts.

But is it just about education? After all Sachin Tendulkar, Dennis Lillee, Steve Waugh and Ian Botham didn’t go to College and they have done reasonably well financially. And surely, you don’t need a college education to prevent you squandering US$400 million like Tyson did?

It clearly goes deeper than that. And there are indeed a few key reasons why it all goes south when an otherwise top performer steps back into life outside the arena.

Let’s go back to the issue of being aware of the world outside their sport. When the going is good, lawyers, agents and fair weather friends abound to feed off the cash cow, and as soon as the money is gone, they vanish into the woodwork, and the bankruptcy court takes over. Retired NBA player Danny Schayes put it very simply, “guys go broke because they surround themselves with people who help them go broke.”

If we look at the examples of sportspersons who slipped into financial trouble, bad financial advice would cover a significant proportion of the populace. Managers and advisors are appointed, not because they are good, but because they are friends.

Between 1999 and 2002, 78 NFL players lost US$42 million because they trusted money to financial advisers with questionable backgrounds. Money is invested blindly, based on advice that turns out to be poor.

As ex-Morgan Stanley VP, who runs financial boot camps for professional sportspersons, says, “chronic over allocation into real estate and bad private equity is the No.1 problem for athletes in times of financial meltdown, and I’ve never seen more people come to me about raising money for those kinds of deals than athletes.”

And as NFL agent Steven Barker explains, “Disreputable people see athletes’ money as very easy to get to”. (Quotes from a Sports Illustrated report in 2009).

Spending way over the top on property, private jets, alcohol and drugs and bad sexual and marital decisions makes up the balance of reasons. From Bjorn Borg, to Mike Tyson to Scottie Pippen to Wally Hammond and hundreds of other famous sportspersons, all fell victim to this malaise.

And unlike bad financial advice, the wrong spouse, the extravagant new private jet, the incorrect sexual decision and that first drug induced high, are all avoidable decisions that anyone can unfortunately make. Having that extra million or ten at the age of 21 is an understandably irresistible temptation.

Looking at this aspect of sports has been a fascinating journey for me. Clearly this is a topic on which one can do a much broader study. But the lessons are clear. Young, successful sportspersons are a vulnerable lot. If they go through the college system as athletes, then it’s the clear responsibility of the college authorities to ensure that they are given as much advice on financial matters and life after sports as possible.

For sports like cricket, with lucrative contracts for youngsters from the T20 leagues, and little chance to go through college in many cases, such advice should perhaps come from the mega rich Cricket Boards like the BCCI, CA and ECB in the form of compulsory “life lessons” classes.

The more money there is in sports, the younger kids will be when they turn professional, and more will be the responsibilities of those in charge of the sport to ensure that there are no more Tony Locks, Wally Hammonds, Bjorn Borgs and Kenny Andersons who throw away their hard earned money while entertaining us with their genius, and perhaps end their lives in financial ruin.

The next time you watch a 19-year old with an US$1 million IPL contract, don’t begrudge him his early financial success, but step back and hope that by the time he ends his playing days, the child within him will be an astute adult who has handled the financial responsibility that will allow him to enjoy the fruits of his labour.