On 24 Jun 1899, an Australian rugby team played for the first time as a national combination against England at the Sydney Cricket Ground.

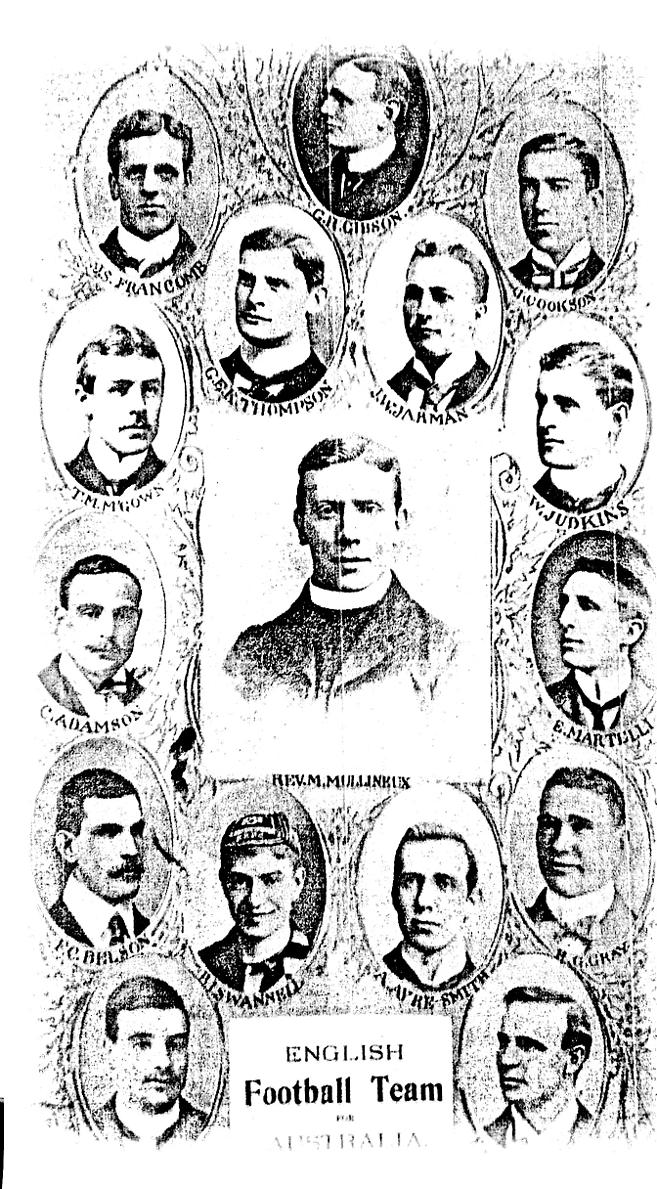

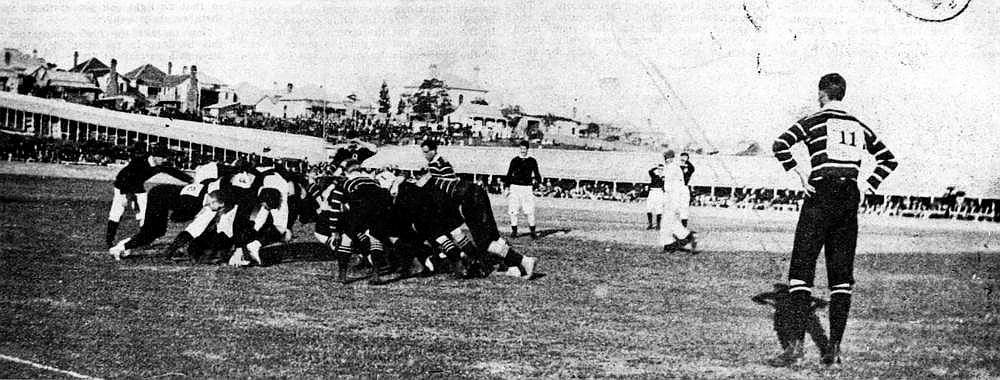

There were players from the other home rugby unions in the visiting side, but at the time it was deemed by the management and the newspapers to be an English team, playing in England’s colours. A publicity photograph of the ‘English Football Team for Australia’, for instance, showed the faces of the players with their manager and sometime halfback, the Rev. MM Mullineux, staring out from the centre spot in the montage. Another photograph taken during the SCG Test is an image of a visiting player kicking a conversion attempt. The caption under the photograph reads: ‘Adamson kicks for goal for England’.

A cryptic cable

At 12.25 in the afternoon of 15 February 1899, the Reverend Matthew Mullineux, a teaching fellow at St John’s College, Cambridge University, received a cryptic reply-paid cablegram from Sydney, Australia: ‘Newspapers here report your Abarataron Tamsomente all aerofobo Widerhakerr sebacica Marzauilla have a team aboloris desabozar. Rand.’

This cablegram was followed a few days later with a letter delivered by the British Post Office giving a full transcript of the cablegram. The use of an elaborate code was clearly intended to prevent the urgent message in the cablegram being passed onto other sports organisations in Australia. A well-informed person about sport in Sydney, for example, might have guessed that ‘Rand’ was AW Rand, the masterful secretary of the New South Wales Rugby Union. But what could ‘Newspapers here report your…’ possibly mean?

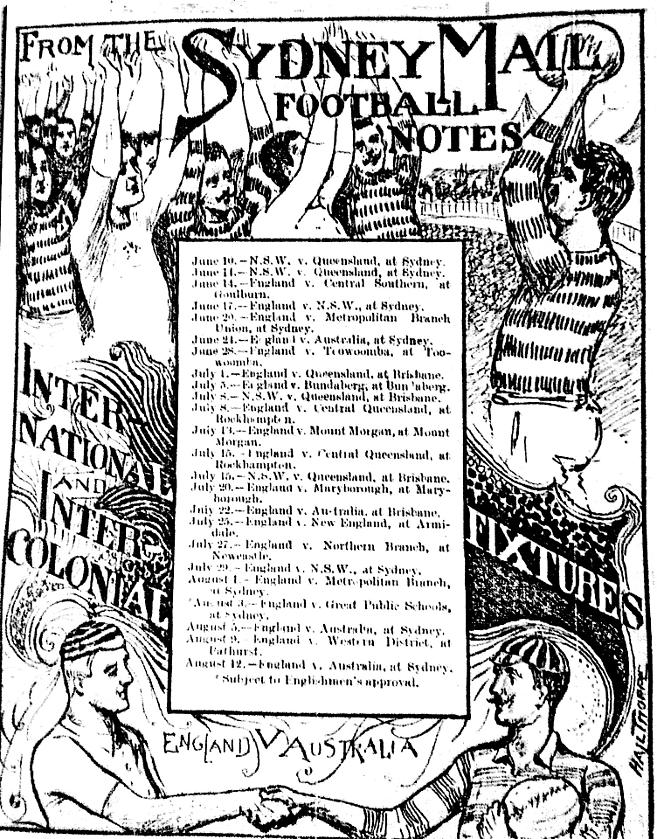

Our well-informed person about sport in Sydney, if he had a special interest in rugby, might remember the small items in recent issues of The Sydney Mail and The Sydney Morning Herald noting that difficulties had cropped up over a proposed rugby tour of an English team to be led and organised by the Rev. Mullineux.

Whether these difficulties were widely known must remain moot. But the fact that the tour was in doubt was the centre of a discussion at a council meeting of the NSWRU held at its room in 109 Pitt Street, in the heart of Sydney’s central business district, on Tuesday 14 February 1899. The motion for discussion was what the NSWRU should do about press reports that ‘the English Team’s visit has been abandoned’.

It was decided after a vigorous debate that a cablegram be sent to England asking the Rev Mullineux if the ‘question of terms’ was the problem. The meeting agreed, too, that the Rev. Mullineux needed to know that the NSWRU ‘must have’ the team and that it would be a ‘serious detriment’ to rugby in the colonies if the tour were cancelled.

The England Rugby Team as depicted in the paper

Mullineux’s offer

The inspiration for the proposed tour came from a letter to the NSWRU, out of the blue, from the Rev. Mullineux. The letter, which exhibited a mixture of boldness and optimistic misinformation, was dated August 1897:

“I should be glad to know if a visit of British footballers to Australia would be welcomed next year. The South African tour last year was a great success and there is a desire among prominent footballers to visit Australia next year. If you think such a visit would be a success, I would be glad to get together a strong team to leave England next year.

“The team would be drawn largely from my own University and that of Oxford and from the Internationals from outside the Universities. We would leave in June and play some 16 to 20 matches before leaving the land again. The financial aspect of the visit we can consider if you decide to send me the invitation to get the team together. Kindly let me know soon. I am sending a similar letter to Melbourne in case Sydney is not one of the centres of rugby union.”

But this is only a whisper

Some time later, on 4 May 1898, The Referee newspaper explained to its readers why the rugby tour had been called off at least until 1899:

“The reason, Mr AW Rand, hon.sec. of the New South Wales rugby union, tells us, is that the gentleman manipulating the strings at the antipodean end could not quite fix things up as he desired in team to reach Australia in time for this football season.”

Specifically what was holding matters up was the Rev. Mullineux’s shrewd and less-than-honest attempts to keep the NSWRU on hold while he tried to organise a follow-up tour to the successful South African tour he had organised in 1896.

The dark clouds of the gathering storm of the Boer War, however, made it obvious that a rugby tour of South Africa by a team of British players – while troops around the Empire were being sent out to that country to put the Boers in their place – was not possible. The Australian tour, therefore, was rushed back into preparation. The gossip writer for The Referee went on to note that “someone whispers that Mr Molyneux (sic), of Cambridge, paused in his organising efforts, and pondered deeply over the fate of his brother sportsmen who play cricket. Then, rather than come along to take the kangaroo down a peg at rugby with a team a doubtful strength, he discreetly postponed the venture. But this is only a whisper.”

The gentleman manipulating the strings at the antipodean end could not quite fix things up as he desired in team to reach Australia in time for this football season

Mullineux’s men

The whisper, in reality, faded away like smoke from a fire. The cryptic message from Rand prompted the Rev. Mullineux into putting his formidable organising abilities into play. He set aside his South African hopes. The tour of Australia was now on. On 20 May 1899, The Sydney Mail, in its sports section, printed a note from a correspondent, ‘Fullback,’ who listed the team that had finally been put together by the Rev. Mullineux: “It adds much interest to the team to know that it contains the best men hailing from England, Scotland, Ireland and Wales.”

The team was: E. Martelli (Dublin University), C.E.K. Thompson (Lancashire), E.Gwyn Nicholls (Cardiff), A.B.Timms (Edinburgh University, G.P.Doran (Lansdowne), A.M.Bucher (Edinburgh Academicals), E.T. Nicholson (Birkenhead Park), Rev M.Mullineux (Blackheath: captain and manager), G.Cookson (Manchester), C.Y.Adamson (Durham), F.M.Stout (Gloucester), J.W.Jarman (Bristol), H.G.S.Gray (Scottish Trials), G.R.Gibson (Northern), W.Judkins (Coventry), F.C.Belson (Bath), J.S.Francombe (Manchester), B.I.Swannell (Northampton), E.V.Evans (Moseley), T.M.McGown (North of Ireland), A.Ayres-Smith (Guy’s Hospital).

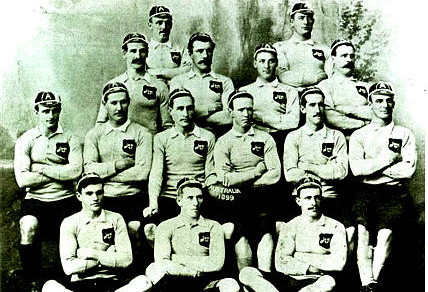

The British tourists of 1899

Eight of the players were internationals at the time (Nicholls, Timms, Doran, Bucher, Nicholson, Stout, Gibson and McGown). JW Jarman later represented England. BJ Swannell – described by Jack Pollard in his magisterial rugby history Australian Rugby: The Game And The Players as “a tough, courageous English-born forward with outspoken opinions” – represented Australia on its first tour of New Zealand in 1905.

The liniment of history might have relaxed opinions, but rugby writers decades later insisted that the Rev Mullineux’s pioneering side was one of the best ever to tour Australia. The team’s record – played 21, won 18, lost 3: points for 333, against 90 – is impressive.

A bit dickey

Before the Rev. Mullineux’s team had even played a match, the Truth newspaper expressed the fear that the colonials could not match the British mother race on the sports field. Truth cast its worried eyes over the Rev. Mullineux team and then made a defeatist prophecy:

“Truth can safely say the safety of the honours of Australian footer look a bit dickey. And it is more than likely they will be carted to England for a longish period of time.”

The first sighting of the Rev. Mullineux’s team in Sydney confirmed that they were “a fine, athletic-looking lot of men.” Reporters, though, were struck by their lack of heft and bulk: “The visitors do not strike Australians as being especially big men.” The feeling was that the weights given for the forwards, who were claimed to be an average 13 stone, were greatly exaggerated. But while the English players were not as beefy as their publicity suggested, “they are all big-limbed and powerful as is natural when it is reflected that to secure county, university and international honours, each man is the pick of a host of athletes.”

But how should the first Australian rugby side be selected? That was the tricky question, give the intensity of inter-state rivalries at the time, the New South Wales Rugby Union had to answer.

NSWRU, the host union for the tour, answered this question by following the precedents set by the cricket authorities. These authorities developed a strategy of loading the selection panel with locals depending on where the cricket Test was played. The Commonwealth of Australia did not exist until Federation in 1901.

The States did exist.

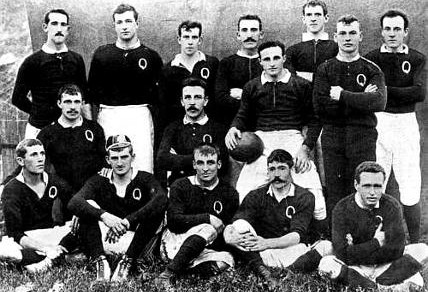

The 1899 Australian rugby team

It made sense in a new venture like creating a national rugby team for this political and social reality to be acknowledged. So a reasonable compromise was created – the first rugby Test side played in NSW blue because the match was played in Sydney. The second Test side in the series saw the Australian side wearing the maroon of Queensland for its Brisbane match.

The selection panel of one Queenslander and two NSW officials announced their team for the first Test on the Monday before the kick-off, which was on the following Saturday afternoon at the SCG. There were nine players from NSW and six from Queensland in the team:

Fullback: R. McCowan (Queensland)

Three-quarters: AS Spragg (NSW), F. Row (NSW, captain), C. White (NSW)

Five-eighths: P. Ward (NSW), WT Evans (Q)

Half: A Gralton (Q)

Forwards: J. Carson (NSW), WH Tanner (Q),W. Davis (NSW), H. Marks (NSW), P. Carew (Q), A. Colton (Q), A. Kelly (NSW), C. Ellis (NSW).

The Australian forward lined out as they were named, in a 2-3-3 scrum formation, with ‘Jum’ (short for Jumbo) Carson and ‘Doey’ Tanner being the hookers. Australian had learnt about scrum positions from New Zealand. Over there, the scrum formation was 2-3-2, with one forward standing off, the ‘wing forward’, protecting his own halfback and harassing the opposition halfback. It was not until the 1920s that English teams had settled scrum positions.

The first forward to arrive formed up in the front row. As the game progressed, as the bigger forwards tired, the English front row positions were taken by the smaller, loose forwards. This is what happened to England during the first Test at the SCG.

The Australian team trained at the Sydney Cricket Ground around 3.30 on the afternoons leading up to the Test under the supervision of W. Warbrick, one of the great men of New Zealand and later Australian rugby. There was no suggestion at the time, as there was when another New Zealander, Robbie Deans, coached Australia, that Warbrick was somehow a ‘stalking horse’ for New Zealand rugby.

There was, in fact, nothing but praise for the team and its preparation.

Bob McCowan at fullback was regarded as the “finest produced” in Queensland. Stocky and dynamic, he was “fast, very clever in handling, kicking and passing the ball, and tackles well.” In an era when the fullback was regarded as a custodian, McCowan was modern in his concept of what the position required: “Indeed, he possessed in a high degree the essentials of a crack three-quarter.”

The team’s real crack three-quarter, the winger Lonnie Spragg, was a prototype of the brilliant outside back that has been one of the enduring glories of Australian rugby, from Dally Messenger, Cyril Towers, Charlie Eastes, Trevor Allen, through to the moderns like David Campese (the greatest of all, in my opinion), Tim Horan, Ben Tune, Dan Herbert, Stirling Mortlock and now Israel Folau.

The first sighting of the Rev Mullineux’s team in Sydney confirmed that they were “a fine, athletic-looking lot of men.”

Spragg was a natural. He did not start playing rugby until he was 17. Two years later he was a Test player. As a youngster bursting into senior rugby, Spragg was described as “possessing rare gifts, denoting a special aptitude for the game… He is as fast, if not actually faster than S. Wickham, dodges like the old Wallaroo winger, yet unlike him, too, he dodges both ways. Spragg is a splendid kick, either place or drop, and is eager and capable on defence.”

Holding the pack together was the formidable front rower James ‘Jum’ Carson and the back rower Charlie Ellis. Carson was regarded as “the best all-round forward in Australia… In the pack, in the loose and on the lineout, he is equally good.” The highest praise that was lavished on Carson was the acknowledgement from New Zealanders that he was as good as any forward in that country.

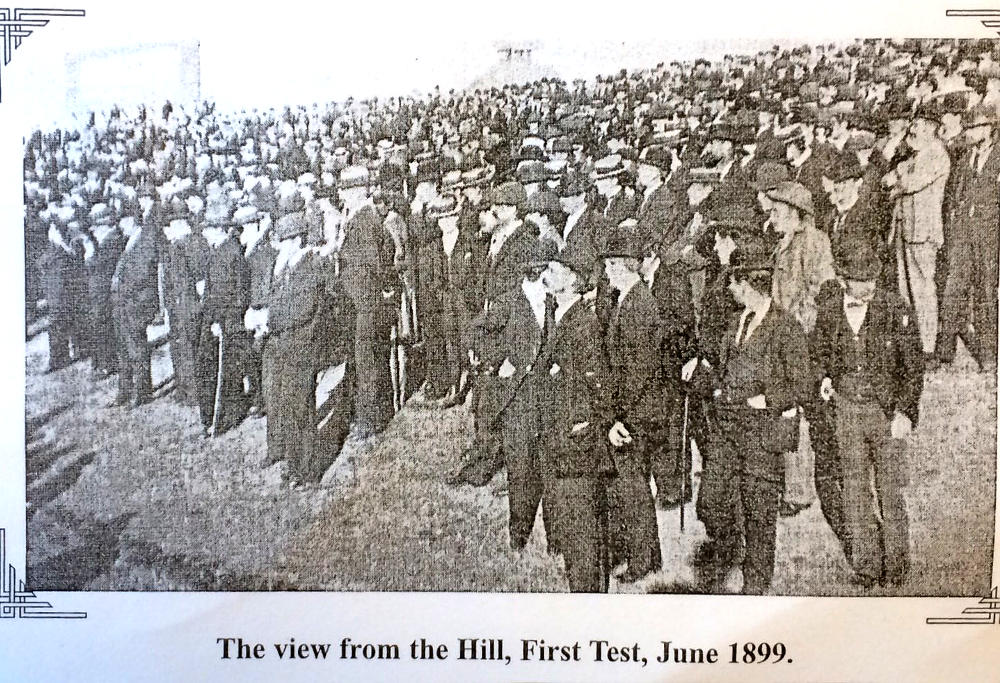

The Sydney Mail on 1 July 1899 carried a series of photographs that give a certain resonance to the great occasion of Australia’s first rugby Test. There is a team photo of the local side, with the players in their Test caps, taken shortly before the game. The shin pads on A. Colton are exposed. P. Ward marks his debut by wearing a colourful sash around his waist to hold his shorts up. Is the sash a present from a girlfriend or a memento from his loving parents? The captain, F. Row, is grim-faced and is sitting in the middle of the middle rank with a fat leather ball resting on his knees. Seven of the players, most of them the more experienced members in the team, wear military-style moustaches that infer they are officer material. The younger members of the side, Spragg and Colton, have a baby-faced toughness about them.

The referee, Christchurch-based WG Garrard, is in the middle of the back row, moustached and wearing the standard white outfit. Garrard was so determined to be impartial throughout the game that he sometimes fed the scrum himself instead of the appropriate halfback.

A controversial first try

Australia won their first Test 13–3. The early part of the Test featured ‘dashing’ play by England. The visitors “returned to the attack with vim”, a journalist reported. A break by G. Cookson was followed with another “brilliant run that reached almost to the Australian line.” England were playing with the panache that was later adopted by British and Irish Lions side in the amateur days of rugby. The game “became extraordinarily fast and things for a moment looked bad for the Australians.” Then came an historic moment in Australian rugby history: the first try in a Test by an Australian side.

Here is the eye-witness account of what happened, written by a rugby writer for The Sydney Morning Herald:

Back again the ball was worked, until in front of the goal Gralton secured and passed back to Evans, who took a flying shot for goal. The ball went high, failed to score, dropped in front of Martelli, who allowed it to bounce, and Kelly and Colton came with a rush. The former jostled the English fullback, secured the ball, and scored a try. Several of the Englishmen appealed for two reasons – for offside and for illegal interference – but the referee allowed the try.

From the press table, in the balcony of the members’ pavilion, the interference appeared to be a simple jostle, but it seemed hard to come to any other conclusion than that Kelly and Colton were offside. There was great excitement among the spectators. Spragg took the kick, but failed to add the extra points.

Peter Jenkins, in his authoritative history of the first 100 years of rugby Tests by Australia Wallaby Gold, summarised 13–3 result this way:

There were just three points in the first half, a try to Australia, but even that came hotly disputed. William ‘Poley’ Evans, playing in the midfield with Ward – the Australians opting for two five-eighths close to the pack and three three-quarters out wide as opposed to the British side’s two centres and two wingers option – attempted a drop goal, only for the kick to land short.

As the British fullback E. Martelli allowed the ball to bounce, two Australian forwards, Ginger Colton and Alexander Kelly, raced through offside. Colton jostled Martelli, gathered the ball and scored. Despite the protests of Mullineux’s men, the try was awarded. Winger Stephen Alonzo ‘Lonnie’ Spragg missed the conversion. The tourists levelled 14 minutes after half-time with a dazzling passing rush, finished in the corner by Gwyn Nicholls. But tries to Evans and Spragg in the closing minutes, as the British fell away in condition, signed off with a flourish the opening page in Australia’s Test match history.

The Reverend’s sermon

The Australian Field published a controversial interview with the Rev. Mullineux at the end of the tour in which he was quoted as objecting to the incipient professionalism he observed throughout the rugby community in Australia. Although Mullineux claimed he has been misquoted, the quotations were so extensive it is unlikely they could they have been invented.

Amateurism was for the Rev. Mullineux, and others of his class in England, God’s work. Rugby, it was argued, could not grow as a recreation if the game was corrupted by professionalism.

Rugby was a game. It was not a trade.

These principles were put under a test while the tour was being put in place. There was news that the famous James brothers, the inventors of the halfback formation, had defected from Welsh rugby and had “gone over to the Northern League and professionalism.”

The behaviour of such ‘professionals’ was seen as an offence against the proper order of society. The only response to this type of attack on amateur rugby and good order in society, therefore, was to contain an outbreak of this plague with total isolation. One of the touring conditions for the players in the Rev Mullineux’s team was that “they must be amateur.”

Rugby was a game. It was not a trade.

When he observed a sort of professionalism being practised in Australian rugby, the Rev. Mullineux was appalled.

What he could not comprehend was that the egalitarianism of ordinary life in Australia meant that there was also an egalitarianism in the way rugby was organised. Because the game appealed across the community, from lawyers, doctors and students through to men who worked with their hands – when they could get a job – there was no objection to talented players getting a small financial reward for their skills.

A rugby player, like everyone else in the working community, was worthy of his hire. That was the belief among rugby administrators in Australia. Being good at rugby was a skill that deserved a monetary consideration as much as being able to read a commercial document.

This belief was sustained by the influx of New Zealanders to NSW and Queensland. New Zealanders had from the beginning of rugby in that country in 1870 accepted that the game should provide some financial rewards to the players. There was a depression in New Zealand throughout the 1890s and many players and former players looked to Australia and rugby as a way of earning their keep until better times arrived.

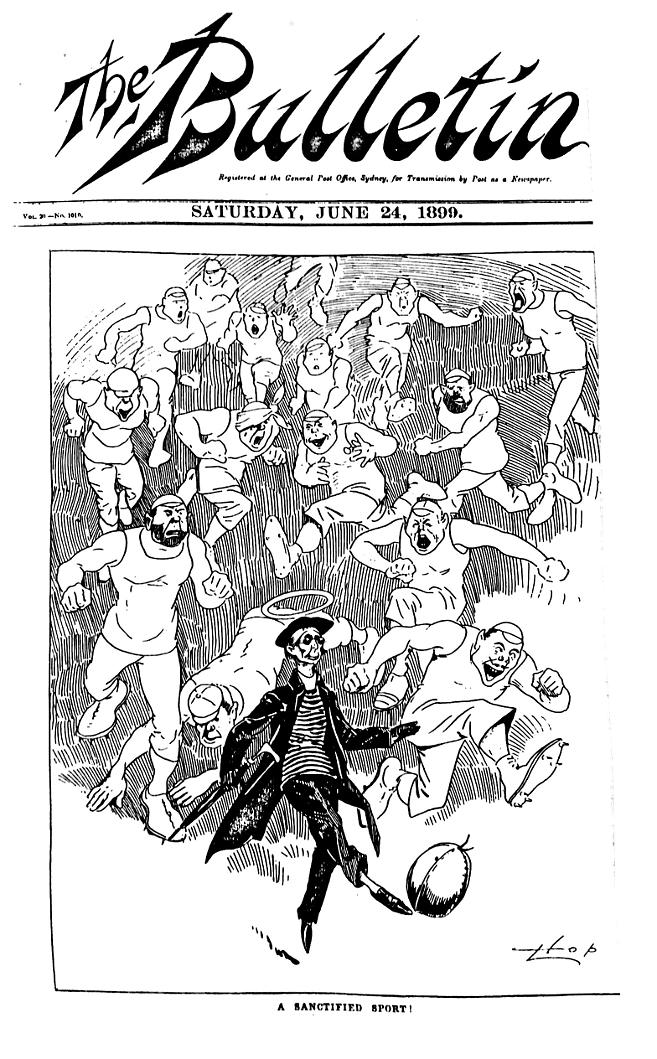

The cover of the Bulletin

The Rockhampton Bulletin in 1892 was moved to issue this warning: “One has only to note the many famous players who have migrated to Charters Towers during the past 12 months to see if professionalism does not exist there, appearances are exceedingly deceptive.”

There is an item in the minutes of the NSWRU of 30 April 1897 that appears to confirm this suspicion: “It was decided that the railway fares of Roberts (the New Zealand player) to Queensland be borne by this union, and that the New Zealand Union be informed.”

Some years earlier, in 1888, the Rugby Football Union held a hastily-convened meeting at the Queen’s Hotel in Leeds, England, which laid down the amateur law to the team of players tentatively selected to tour Australia. The Daily Telegraph in its report of what were supposed to be “strictly private” discussions about the belief that GP Clowes was a professional player, was able to establish that the delegates formed “the very strong opinion that others composing the Australian team have also infringed on these laws.”

When the players finally returned from the Rev. Mullineux’s tour they were required to sign an affidavit that they had received no ‘pecuniary benefit’ from the tour.

By 1899 the professional ethic had become ingrained in Australian rugby. Players were being paid to go from their country (New Zealanders, in most cases, but some British players migrated with their rugby boots also) to Australia, from one state to another and from club to club. Clubs were being paid, as well, to hire professional trainers. Costs incurred by injured players were being covered by the NSWRU.

The minutes of the NSWRU’s meeting of 6 February 1899, when the details of the tour by the Rev. Mullineux’s team were being finalised, carried this item under Correspondence: “Letter from Kelly – re Medical Expenses amounting to 2 pounds, 11 shillings and 6 pence incurred through being injured while playing football. Mr Henderson moved and seconded by Mr Lane that account be paid.”

The Truth reported accurately, therefore, in May 1899: “By slow degree the old order of things has changed, and in the new regime, controlled and managed by young men with up-to-date ideas, every senior club is entitled to a grant of 10 pounds for the purpose of defraying the costs of a trainer. This to old hands sounds suspiciously like professionalism, but it is nothing like what will come… Clubs have the permission of the Union to arrange matches among themselves, the gate takings of which they divide equally. It must be obvious that contests played under these conditions are not for sport but for monetary gain – that those engaging in it are doing so not for the love of it but for what they can get out of it. In other words, the real issue of the game is not so much the object of achievement as that the club coffers will respond to the ring of shekels.”

The article went on to criticise the fact that the players playing inter-State matches were ‘paid’ by their local union at the substantial amount of five shillings a day. This allowance was “ostensibly a wine bill expense.” But, as the Truth fearlessly pointed out, the wine bill expense was exclusive of travelling expenses. It was paid to players whether they drank wine or water. One player with private means refused his expenses but was told that if he did not accept them, someone else would. He took the money.

The Truth then articulated the arguments against this virus of professionalism that the Rev Mullineux made so emphatically throughout England’s tour:

“To those who know anything about Rugby football in the old countryland, the acceptance of this money constitutes a distinct breach of the rules, and any player who is proved to have done so is regarded as a professional… Once let it get its hold of NSW football and the game will become not one of pleasure but one of business. And we in Australia know by past experience that when a sport becomes a matter of business the results in the main are decided by pounds, shillings and pence.”

The Queensland rugby team of 1899

The Rev. Mullineux’s constant attacks on the growing professionalism of Australian rugby had their desired effect. Administrators changed direction. The amateur ethic became settled policy. Professionalism was abolished. Rugby administrators in Australia (unlike their counterparts in New Zealand) made a conscious attempt to create an exclusive game for the middle and upper classes. The consequences of this elitist policy were dire for the growth of the game. A row over injury payments broke out in Sydney in 1907. The NSWRU, following the amateurism edict of the Rev. Mullineux, refused to make any payment to players who had been injured in a rugby match.

This break with the practice before 1899 was especially hurtful to men in labouring jobs. They could not do these jobs with broken legs or arms. Injuries like this in rugby, moreover, were so rife that the Bulletin referred to rugby in this period as “the undertaker’s friend”. Players who had clerical jobs could continue with their work, despite their injuries.

The outcome of the NSWRU’s lack of care for its injured players was a players’ revolt against the rugby establishment. Rugby became divided by The Great Split of 1907. The rugby league code within a year was on the way to becoming the dominant winter sport in Sydney and Newcastle, and later in Queensland. With this split, too, came the end of any possibility of Australia becoming the dominant rugby nation in world rugby.

The great rugby league clubs of Sydney, stretching from Manly to Penrith, to Newcastle in the far north and Wollongong in the far south should have been the Australian rugby equivalent of the 20 or so provinces that have given New Zealand rugby its enduring heartland strength. But this was all lost to the curse of the Rev. Mullineux’s amateur obsession.

Oh rugby’s lost: Messenger, Churchill, Gasnier, Irvine, Fulton, Kenny, Lewis, Langer, Daley, Meninga, Johns, Fittler, Inglis, Thurston and Slater…

This circle of dissident rugby players embracing a professional game, rugby league, while the traditional rugby game continued to be administered with a restrictive amateurism was finally completed in May 1995 when the NSWRU issued an historic statement headed: Rugby is no longer amateur. The statement was issued before a similar ruling was handed down by the IRB/World Rugby. It made the obvious point that “the rugby world has been remunerating players and coaches in various ways for a very long time… Amateurism as a concept is out-moded and should be dispensed with in the modern game.”

This historic statement, which was inspired by News Ltd’s raid on rugby league to set up Super League, which in turn threatened to cannibalise rugby union of its players, was the breakthrough that led to the News Ltd deal to finance rugby into buying the television rights for rugby in South Africa, New Zealand and Australia. This SANZAR deal forced the hand of the IRB/World Rugby. It was agreed 100 years after the Northern League split that rugby could not remain an amateur game. Rugby from now on was to become an ‘open’ game, professional to whatever level the administrators wanted to make their payments.

The famous Sydney club system is created

On the Monday before the first Test in 1899, The Sydney Morning Herald editorialised on the joy of rugby: “The strenuous struggles of the opposing parties, the quickness and readiness of the players, the breeziness of the atmosphere in which all games are played – all stimulates the interest of the onlookers.” The Rev Mullineux was complimented for bringing a team to Australia that was “utterly indifferent” to gate takings: “They have come here for the love of the game, and some of them … are really losing money on the tour.”

But as Dr Thomas V. Hickie points out in his history of suburban club rugby in Sydney, The Game For The Game Itself, the tour provided a tremendous fillip for rugby throughout Australia:

“Crowds for Brisbane and Sydney premiership matches leapt to hitherto unknown levels, with 15,000 for needle matches not uncommon.”

The NSWRU pushed ahead with its restructuring of the Sydney club system, which had been discussed throughout the 1890s and held back by the England tour. In 1900 the inaugural district premiership competition was launched. This competition is still in place, and remains one of the jewels in the crown of Australian rugby.

Playing for a nation that doesn’t exist

The ‘Australian’ rugby team that contested its first Test against England did so at a time, 1899, when Australia as a constitutional entity did not actually exist. There was no Australian flag and no Australian anthem in 1899. The concept of a distinct Australian citizenship with Australian passports rather than British passports did not come into force until Australia Day 1949. Australia as a national construct, at least until Federation in 1901, only existed when a national rugby side or cricket side, literally, became Australia’s team.

It was in sport, essentially, that the sense of being something other than British developed in Australia. Sport released the national identity. General William Booth, the founder of the Salvation Army, reported after his visit to Australia in 1892: “The hilarity and vigour of youth leads to a love of excitement, with all its consequent dangers. One manifestation of this is to be found in the terrible hold which gambling has on Australia… Another manifestation of the same thing is the tremendous passion for outdoor sports.”

It is a truism of sociology that sport and culture are like Siamese twins. But, as Chris Laidlaw, an All Black and Rhodes Scholar points out, these twins are often in denial with each other. Cultural groups in Australia looked to England at the end of the 19th century in a sort of cultural cringe: sport looked within Australia. The national identity, therefore, was forged by the national sporting teams.

The first rugby Test between Australia and England actually coincided with the vote on Federation: 107,274 people in NSW voted for the Federation Bill: 82,707 voted against. The majority of 24,573 was regarded as a handsome one by the political class. Did the prospect of 30,000 people at the Sydney Cricket Ground cheering on a national rugby team and the patriotic excitement that a victory over the tourists from ‘the old country’ convince many of them to vote for the future of a new, united but federated nation?

The opening sentence of the editorial in The Maitland Daily Mercury which celebrated the Federation Bill victory was quoted in the Sydney Morning Herald directly beside that newspaper’s report of Australia’s victory in the first rugby Test. That sentence could have represented both results: “The cause of Australian union has triumphed gloriously in New South Wales.”

The joy of rugby

As Australia moved into nationhood, rugby and the joy that the game provides for players and supporters grew in popularity. The catalyst for the rugby side of this equation was the tour of the Rev. Mullineux’s team. Unlike England sides of later generations, this side played exhilarating rugby. Their passing game based around strong-running three-quarters became the traditional Wallaby style. The science of rugby, too, was exposed by England as a winning way in their 3–1 series win. Australians had previously seen rugby merely as a battle of brawn.

Young players flocked to grounds to play the game. Huge crowds gathered to watch significant games. Jack Pollard put the 1899 tour in this context:

The visit excited great public interest, and gave rugby a clear advantage over its rival codes. For almost a decade, public support for international and interstate games made rugby the pre-eminent winter game in NSW and Queensland. From the turn of the century, the influence of the GPS schools spread to Catholic colleges, associated schools and public high schools.

Thousands of young men started playing the game, at first with no thought of playing for their State or for Australia. A lot of them played the game for fun after they left school, believing in the concepts of amateurism and sportsmanlike behaviour they had learnt at school.

This last comment raises an important issue. The England team was scheduled to go to New Zealand. The NSWRU refused to pay for the cost of the journey across the Tasman Sea, however. This intransigence proved to be a godsend for New Zealand rugby. Without the sermonising of the Rev. Mullineux, New Zealand rugby officials allowed their game to remain quasi-professional.

Report and picture from the Sydney Mail

The irony was that when the split between the rugby codes came in Australasia in 1907, a New Zealand rugby league side was put together to tour Britain with Dally Messenger, Australian rugby’s superstar at the time, included in the side as an honorary New Zealander. There is a photograph of Messenger in the black jersey with the silver fern emblem. But while rugby league displaced rugby union as the main rugby code in NSW and Queensland, it was beaten off to marginalisation in New Zealand. New Zealand rugby was saved (as France was after World War II) by the fact that there was no real reason for the better rugby players to make the switch to league as they were already making money out of playing the rugby game.

Toasting the future in champagne

Australia won the first Test at the SCG 13–3. England won the second Test at Brisbane’s Exhibition Ground 11–0. The third Test at the SCG was won by England, 11–10. The fourth was won by England, again at the SCG, 13–0.

Played in heavy, relentless rain and stormy winds, the power play in the England forward and the skills and pace of the backs proved too much for the now embattled, out-gunned Australian side to handle. Peter Jenkins in Wallaby Gold singled out the Welsh genius Gwyn Nicholls for special praise:

“Still, the majestic Nicholls left his imprint on a two-try victory as the four three-quarters policy used by the tourists found the Australians frequently short on defence when the play moved wide. The Referee enthused: ‘Nicholls is as great a player in the rain and mud as he is on a fine day… It was remarkable how well he kept on his feet while running fast and resolutely.'”

Without the sermonising of the Rev Mullineux, New Zealand rugby officials allowed their game to remain quasi-professional.

On the evening of the last Test, the England footballers were entertained by the NSWRU at Tattersall’s Hotel in central Sydney. About 160 men were present. The evening began with a series of toasts. JJ Calvert, the president of the NSWRU, in proposing a toast to “the English team and the Rev Matthew Mullineux,” said the English players could forget the “little pinpricks” they had suffered during their tour after their splendid victory earlier in the day: “If you are unable to carry the ashes, you have to take the mud.”

The Test had been played on a wet field and this remark was greeted with laughter. The toast was concluded amid “great cheering.”

The Rev. Mullineux, a small man, was asked to stand on a chair so that he could be seen at the back of the room as he made his reply. He was not out here in Australia as a representative of English rugby football, he said, but he felt he had a duty to speak against anything that was not conducive to the game being played in a sportsmanlike manner. As a clergyman, he denounced anything in the game that was ‘unmanly’. What he said should not be seen as ‘carping’. He objected to the Australian trick of holding a man back when coming away from the scrum: “I am told that the Australian remedy is to bite the hand but we have not mastered the art of cannabilism.” Shouting to an opponent for a pass was the lowest thing he had heard of: “Please blot these things from your football, for instead of developing all that is manly they bring forth all that is unmanly. (Cheers)” The trip was now virtually over but he wished to say that it had been one of “joy and delight”, a remark that brought forward further effusions of cheers.

The toasts were honoured in Royal Maximum Champagne.

1899 and all that

The 1899 tour by the Rev. Mullineux’s team globalised Australian rugby. The money that poured into the coffers of the NSWRU was used to bring the first New Zealand national side to Australia in 1903. This was the beginning of one of the greatest rivalries in world rugby. That 1903 tour by New Zealand, in turn, provided the funds for the first tour of Britain by a national Australian side in 1908. This side, the Original Wallabies, won a gold medal for rugby at the London Olympics. This was Australia’s first Olympics gold medal for a team event.

When the Wallabies run out on to Suncorp Stadium at Brisbane on 11 June 2016 to play England in their three-Test series they will have played 589 Tests, won 303 of them, lost 269, drawn 17, recorded a winning percentage rate against 25 different opponents of 51.44 per cent, scored 12,260 points, conceded 9987, for a plus total of 2273.

There is an element of the amateurism curse of the Rev. Mullineux buried in these statistics, however. From 1899 to the end of 1995, the amateur era of world rugby, the Wallabies played 333 matches, lost 179, drew 11, for a 44.59 winning percentage. In this same period there were 19 Tests played against England, with the Wallabies winning 12 and losing seven for a 63.15 winning percentage. In the professional era, from 1996 to the end of 2015, the Wallabies have played 256 Tests, won 160, lost 90, drew 6 for a 63.67 per cent winning record. In that same period the Wallabies played England 25 times, won 13, lost 11, drew 1, for a 54 per cent winning percentage.

In summary, these statistics (from Matthew Alvarez, the honorary statistician of the ARU) suggest that the Wallabies were more successful against England when they followed the strict amateur rules espoused by the Rev. Mullineux. But after rugby became an open professional code in 1996, the Wallabies were more successful against all other teams, except England, than they had been in their amateur days.

And all the glorious rugby embedded in these statistics had its origins when a worried secretary of the NSWRU walked down Pitt Street in the central business district of Sydney to the telegraph office and sent a coded cable to a rugby-mad Anglican priest living in the cloisters of Cambridge University.

Banjo Patterson wrote a poem about the Rev. Matthew Mullineux. The first stanza serves as a memory of that priest.

I’d reckon his weight at eight stun eight,

And his height at five foot two,

With a face as plain as an eight day clock …

Plays like a gentleman out and out …

Hard to get by as a lawyer plant,

Tackles his man like a bulldog ant,

Fetches him over too,

The Rev. Mullineux.

Written by Spiro Zavos.

Spiro is a founding writer on The Roar, and long-time editorial writer on the Sydney Morning Herald, where he started a rugby column that has run for nearly 30 years. Spiro has written 12 books: fiction, biography, politics and histories of Australian, New Zealand, British and South African rugby. He is regarded as one of the foremost writers on rugby throughout the world.

Design and editing by Patrick Effeney