WATCH: Freddy Flintoff's son dominates County 2nds game batting exactly like his dad

Check out some of the short-arm pull shots from Rocky Flintoff!

On a warm summer’s day in England in 1993, one of the best players of spin in the English team, Mike Gatting, would leave an innocuous looking delivery pitched outside his leg stump, to glance back with disbelief a moment later and see his off stump dislodged by the prodigiously spinning ball from Shane Warne.

The delivery, which would go into cricketing lore as the ‘Ball of the Century’, would not only seal Warne’s reputation as a master of his craft, but once again make the art of leg spin bowling fashionable in an age when it had started to lose its allure among the youth in the earliest homes of the sport, England and Australia.

While Warne might justifiably be credited with making it mainstream again, the wiles of leggies and their variations have fascinated cricket fans for more than 150 years, from the time that overarm bowling with the straightened arm came into being.

Bernard James Tindal Bosanquet was an Etonian who started his career as a batsman and a fast bowler at the turn of the twentieth century who, perchance, invented the googly from an experiment while still a teenager.

While the carpet on the billiard table at home was being relaid, and the boys could not get a game, 14-year old Bosanquet joined his brothers in spinning a tennis ball across the slats. This set him experimenting to see whether it was possible to spin a ball in such a way that it appeared to be going one way but actually went the other.

A few years later, when bemused batsmen were returning in droves to the pavilion, shaking their heads at a leg-break delivery that should have spun away to the offside but had instead knocked over either their stumps or hit the pads before them, the Wisden Cricketer’s Almanack was to remark: “How he manages to bowl his off-break with a leg break action, one cannot pretend to say.”

In his 1801 book, ‘Rules and Instructions for Playing the Game of Cricket, as practised by the most Eminent Players’ – the first book of instructions written on the art of cricket, Tom Boxall, generally acknowledged to be the first man to bowl underarm leg breaks, had said: “Although the ball is tossed straight to a mark, yet it must not roll straight, if it does not it will not twist after it hits the ground: when the ball goes out of a bowler’s hand he must endeavour to make it twist a little across, then after it hits the ground it will twist the same way as it rolls when it goes from the hand.”

A hundred years after Boxall, with straight elbowed over-arm bowling now the only legitimate form, Bosanquet went a step beyond Boxall’s principle. He invented the googly, where the ball after hitting the ground, twisted or spun in the opposite direction after it left the hand. Leg spin bowling would never be the same again.

Bowling the googly was not however as easy as someone like Bosanquet could make it look, and even the most eminent bowlers of the time found that if they wanted to be injury free and have longer careers, it was sometimes prudent to stick to the traditional leg break.

Charles Marriott, the brilliant Kent leg spinner who was to become a legend in his own time in County Cricket, described what happened to him while playing for his school in Ireland;

“One day at a net I had an astonishing spell, when I struck a perfect length and had everyone completely tied up including our professional, who took a turn with the bat for the last minute or two. It went to my head. When it was time to pack up, I shouted ‘one more’ and ran up determined to bowl the googly to end all googlies. What actually happened was a horrible stab of pain in my right elbow, and I found myself out of the XI for the next three matches.”

Marriott rarely bowled googlies after that in his career, sometimes just slipping in one in his fourth or fifth over to keep the batsmen on their toes. He perceived that the threat was enough for his leg breaks to be effective, and remarked that he “never felt it was worth the effort” to bowl it regularly.

Despite his undeniable talent, Marriott played just one Test against the West Indies in 1933 at the age of 37. He took 11 wickets for 96 runs including a six-wicket haul, all with an average of 8.72. In another of those bizarre twists of fate, he was never picked for England again and is the only ‘One Test Wonder’ to have taken more than seven wickets.

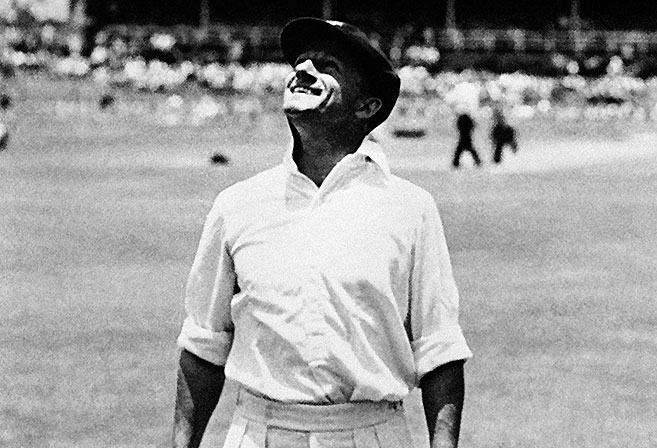

And then there was Clarrie Grimmett. Making his debut for Australia at the age of 33, Grimmett was to become an indispensable part of the Australian attack for the best part of a decade and would make the googly his own like no one had done before and none would afterwards.

As importantly, he would invent the flipper. This delivery, delivered with a more round-arm action, had backspin rather than topspin, so floated on to a fuller length before skidding into the right-hander.

These two would, in fact, be such a significant weapon in his armoury that in the latter part of his career, he would have a bitter run-in with Don Bradman, who would accuse him of having forgotten to bowl the leg break in his eagerness to bowl the googly and the flipper.

In his angst, so the story goes, Grimmett would bowl the Don with a leg break in The Grimmett-Richardson Testimonial match and give him an audible verbal farewell, pointing out the obvious about the ball which had dismissed him.

(AP Photo, File).

Not only would he cause himself and Richardson considerable financial loss from Bradman’s early dismissal – which was guaranteed to keep away the crowds – but Grimmett would never play for Australia again despite having taken 44 wickets at 14.59 in his last series in South Africa, 1935-36, and 25 at 26.72 in his last Ashes in 1934.

Over his career, Grimmett would play 248 first class matches, from 1911 to 1941 and take 1424 wickets at an average of 22.38. He would take five or more wickets in an innings 127 times and match hauls of ten wickets or more on 33 occasions. He would also play 37 Tests between 1924 and 1936, taking 216 wickets at 24.21 runs a wicket.

He also remains to this day the only bowler to have taken 200 Test wickets in less than 40 Tests.

But the bowler who would truly inherit Bosanquet’s mantle of being a mystery bowler would be an ex-Australian serviceman, Jack Iverson.

Unlike most cricketers who made the game their careers having taken up cricket at a young age, Iverson would get to the age of 30 without ever having played any serious cricket.

Having returned to Melbourne from the Second World War, Iverson rejoined his father’s Real Estate Brokerage business, got married and had a daughter. Iverson would be inspired by a game of Blind Cricket and the attitude and enthusiasm of those playing it, which he happened to witness while taking a walk with his wife next to the Melbourne Cricket Ground.

He would try out for the Third Division District team to see if his long admired unusual ability to spin a table tennis and tennis ball could translate into success in the real game, which he had played less than seriously in his service days in Papua New Guinea.

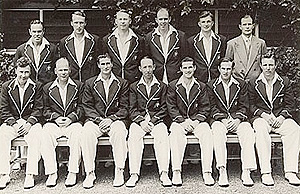

Earning the unfortunate nickname of ‘The Freak‘, for his unplayable bowling, wherein he had variations even more difficult to pick up than the standard googly, Iverson would go from turning out for his first Third Division District match at the age of 31 to representing Victoria in the Sheffield Shield and then Australia, all within two seasons.

Comparing Grimmett and Iverson, Gideon Haigh in his magnificent biography of Iverson: ‘Mystery Spinner‘, would say: “Jack Iverson belongs more truly to a deviant strain of bowlers, also liberated by the googly, but related primarily by intent.”

So unusual was his bowling, that when Iverson was picked for his first Test in 1949 ahead of all of Australia’s frontline spinners, Ashley Mallet, opined: “Bosanquet, the creator of the ‘Bosey’ or ‘googly’ ball put his complete trust in something tangible, something which could be developed and improved upon, but I think the Iverson invention will die with the genial creator. I am not condemning the Australian selectors for choosing Iverson in preference to McCool, Ring, Benaud or Fred Johnston, but I suggest that it is dangerous to place all your confidence in a machine for which you can’t buy spare parts.”

When you read Iverson’s instructions about how he bowled, it becomes clearer how unusual he was as a bowler: “Place the ball between the thumb and third finger. Then bend back the middle finger into the palm of the hand so that the first knuckle joint of that finger rests behind the seam of the ball. When the bent back finger is straightened quickly, it acts as a spring and propels the ball over the top of the thumb in the direction it is intended to break. The index finger plays little or no part in the action.”

As Haigh continues in his biography of Iverson, “From this grip, Jack was able to produce three different deliveries: a googly, spinning clockwise, a top spinner, rotating forwards, and a leg break, running anti-clockwise. There was no twist of the wrist; all that altered was the positioning of the arm, with the unifying principle that the ball spun whichever way the thumb pointed: for the googly, it pointed to leg; for the toppie, it pointed straight at the batsman; for the leg break, it pointed to off.”

Needless to add, no normal leg-spinner before or since has been able to follow his instructions and replicate his mystery.

Unfortunately, that was the only Test series Iverson was to ever play. As his 75 wickets at an average of seven runs each on the tour to New Zealand that preceded the Test series against England showed, batsmen at the highest level failed to read him.

The English batsmen were no exception and he ended up bagging 21 wickets in the Tests that he played at an average just above 15, with a best of 6-27 in the third Test.

During the fourth Test at Adelaide, he suffered an ankle injury when he trod on the ball. He played in only one game in each of the next two seasons and then gave up cricket altogether, fading away from public memory for 60 years until Gideon Haigh, with his outstandingly researched biography, reinstated him in his rightful place on the pages of cricket history.

When Iverson made his debut, he did so ahead of another tall, well-built 19-year old leggie by the name of Richie Benaud, a man that Shane Warne later referred to as the “Guru of leg-spin bowling“.

The compliment was well deserved, for, as Amol Rajan said in Benaud’s obituary in The Independent, “his true legacy came in passing on such wisdom as he gleaned to future generations, seeing himself as a mere steward of the noblest calling in cricket, which is the art of leg-spin.”

Benaud took on the mantle of leg spin bowling from Grimmett and Bill O’Reilly and made the art his own. He developed a flipper that was different from Grimmett’s for Benaud knew that he was not a huge turner of the ball.

He varied the angle at which he released the ball, which made his flipper very difficult to play.

Since he didn’t spin the ball much but achieved significant bounce, “he made a virtue of the extra bounce by using a leg-slip long before it was fashionable, bowling from a wide angle over the crease on a line of middle and leg stump.

He was also among the best exploiters of a silly mid-off position, encouraging batsmen to drive leg-breaks, then slipping them the top-spinner and watching with glee as the extra bounce meant they got to the shot early and looped the ball straight to the fielder“, as Rajan aptly describes it.

The 1960’s and 70’s into the 80’s was a period when cricket was beginning to be truly an international sport, and leg spinners were emerging from countries other than their bastions in England and Australia.

Not surprisingly, the aura of mystery that surrounded the art also got transferred to these new homes.

Bhagwat Chandrasekhar emerged in India from scarcely more believable circumstances than Jack Iverson had done.

An attack of polio in childhood left his right arm withered, but Chandra turned his handicap into an advantage. His initial decision was to be a fast bowler, but having long been an ardent admirer of Richie Benaud, Chandra, as he was popularly known, decided to become a leg spinner, albeit an unusual one.

Batsmen didn’t know quite what to expect from him and sometimes neither did Chandra himself, as he once admitted. After a long, bouncing run-up, he delivered sharp googlies, unplayable top spinners and leg breaks at or near medium-pace from the back of his hand with a whipping action.

In a wonderful spell of leg spin bowling at The Oval in 1971, Chandra single-handedly dismissed England with a spell of 6 for 38 and secured India its first Test victory in the country.

The performance was later to be voted India’s bowling performance of the century. His pace, spin and variety, ensured that both batsmen and umpires were kept on their toes.

Generally, a lovely soft spoken man, his sharp wit was in ample evidence when he was riled.

His encounter with a Kiwi umpire has become a part of cricketing folklore. On the 1976 tour of New Zealand, with every one of his LBW appeals having been turned down by rank bad umpiring decisions, Chandra famously bowled his man with a googly and appealed vociferously to the umpire. Seeing the puzzled look on the umpire’s face, Chandra quipped: “I know he is bowled, but is he out?”

While Chandra was weaving his magic in India, across the border in Pakistan, a wily leg break bowler in the more classical mould, Abdul Qadir, was making his mark as a young prodigy.

As Scyld Berry said in Qadir’s Cricinfo profile. “Cricket has Abdul Qadir to thank for keeping wrist-spin alive through the darkest years of the late 1970s and ‘80s.”

Berry goes on to say: “Qadir’s action was a wonderfully extravagant routine, and he admitted more than once that it was contrived as a spectacle to distract batsmen. Variety was the key; it was said he had six different deliveries per over. Like the Andy Roberts bouncer, Qadir was said to have two different googlies. The flipper was often equally lethal though much often depended not on his ability but on mood.”

Berry, however, dabbles dangerously in hyperbole when he describes Qadir’s bowling thus: “It is impossible to believe that wrist-spin has ever been bowled better than Qadir did in his home city of Lahore in 1987-88, when he took 9 for 56 against England. Graham Gooch, who faced him that day, said Qadir was even finer than Shane Warne.”

The effusiveness is certainly overdone for a record that shows 236 wickets from 67 Tests at over 32 runs per wicket.

It is however not debatable that Qadir was indeed a wonderful leg spinner to watch and equally difficult to play, and with his mystery deliveries and combative personality, was a fitting descendant of a long line of unusual leggies cricket has been blessed with.

Hyperbole, on the other hand, would perfectly be in order when one speaks about the man who inherited the mantle from Qadir from the other side of the border, India’s Anil Kumble.

Kumble was a leg spinner of a kind as different from Abdul Qadir as possible.

It was the tall and fast leggies of the past, Bill O’Reilly, Richie Benaud, Jack Iverson and Bhagwat Chandrasekhar that Kumble modelled himself on.

Rahul Bhattacharya described it well on Cricinfo when he said this about the bowler who was to win more matches for India single-handedly than anyone before him: “Kumble traded the legspinner’s proverbial yo-yo for a spear, as the ball hacked through the air rather than hanging in it and came off the pitch with a kick rather than a kink.”

As if 619 wickets from 132 Tests was not astonishing enough, against Pakistan in Delhi in 1999, on an unforgettable winter afternoon, Kumble bowled unchanged for over three hours and picked up all ten wickets to give India her first Test victory in 20 years over their traditional rivals.

It was only the second time in Test cricket history, since Jim Laker performed this feat in 1956 against Australia, that a bowler had taken all ten wickets in an innings, and the first time anyone had achieved it in a single spell.

As Kumble was scything through batsmen with his fast leg spinners flippers and googlies around the world, there appeared down under, the true descendant of the best of the craft practised by the long line of Aussie leggies led by Grimmett, Mallet and Benaud.

(AAP Photo/Jenny Evans)

Shane Warne arrived on the scene in 1992, without much fanfare, picking up just one wicket for 150 runs from 45 overs against India on his debut at Sydney, giving no hints of the wonders the future should expect from this blonde Victorian.

708 wickets from 145 Test matches and 15 years later, having bedazzled the world with his guile and destructive ability, when Warne rode into the sunset, he would leave a vacuum in world cricket that the bare stables of leg break bowling from England to India and Australia have not been able to fill for a decade.

Will those oversized shoes ever be filled?

Indubitably so.

But which nation will produce the next Grimmett, the next Iverson, the new Kumble, the new Warne?

Whichever corner of the world he emerges from, it is safe to say that the flame of the candle of leg breaks and mystery deliveries, which flickers today, will once again brightly shine in the none too distant future. The world will embrace with undisguised relief the arrival of the new messiah from the land of leg breaks.