I’m heading south on a date with sports history. As we cross the Sydney Harbour Bridge, most of my fellow bus passengers look up from their mobile phones to take in the vista that has opened up. Even if I’ve seen it a million times, I can’t help staring at the harbour; the water a steel grey in the early morning light.

The dark foliage of the Royal Botanic Garden frames Farm Cove, where warships on the Royal Navy’s Australia Station, such as HMS Rosario, used to moor in the nineteenth century. Between the Bridge and Fort Denison, I count four ferries on the harbour. One of them arcs past the Opera House headed towards Sydney Cove, on the same trajectory as a convict transport 200 years ago.

As we come off the bridge into the CBD proper, there’s an enormous cruise ship alongside the Overseas Passenger Terminal. Its passengers disembark at almost the same spot where convicts of the First Fleet, accompanied by their red-coated guards, stepped ashore in 1788.

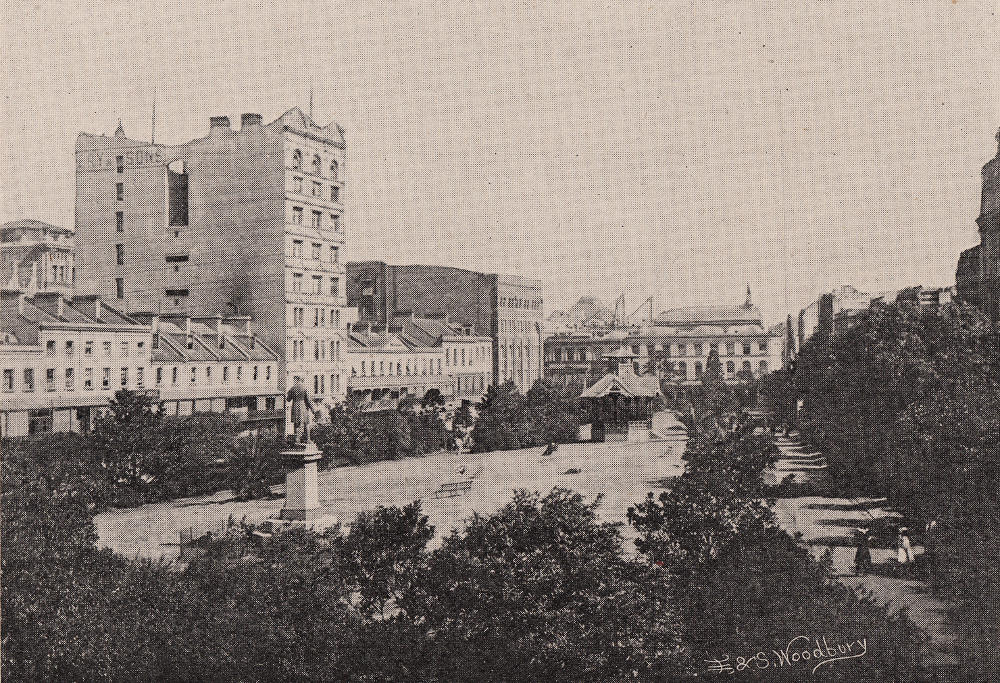

Wynyard Square circa 1897. (Image: State Library of NSW, CC BY-NC 2.0)

The bus stops at Wynyard Park. It’s a rare thing in Sydney, this green space. Unlike the commuters scurrying off to the steel and glass office buildings nearby, this is my destination. Because if sport is your religion, and you worship any of the codes of football played in Australia, this park is holy ground!

Last year, I wrote a piece on the beginnings of rugby league in Australia – ‛All Blacks, All Blues, All Golds: The birth of Australian Rugby League’.

It got me thinking about the origins of the other codes of football in this country. Where could I find the roots to Australian football, rugby union and association football? What was there before these sports existed? If I wanted to know more, how far back would I have to go?

The only solution was to start at the very beginning of European settlement in 1788 and trace forwards.

This is not meant to be an academic treatise, merely the musings of a sports lover using newspaper archives, with a few diversions thrown in, in an attempt chronicle the origins of Australia’s football codes. So I would encourage you to join me on the journey and maybe we can even have some fun along the way.

The story begins with those infamous red-coated soldiers.

The first mention I could find of the word ‘football’ in an Australian newspaper was in a poem published in the Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser on August 24, 1816:

“Now for my part, I think the thing needs no dispute

That’s as hard to defend as it is to refute,

That’s uncertain as foot-ball which side shall obtain,

While the wreath to the victor requites not his pain;”

The use of the term ‘football’ (or ‘foot-ball’) as a metaphor for something being kicked, bounced around or as an uncertain outcome becomes more common in succeeding years. It shows that football as a pastime must have been familiar to the earliest European settlers.

But what about people actually playing the game? The first mention is in the Australian newspaper on 24 July, 1829. It describes football being played by the red-coated soldiers:

“The privates and others of the garrison have lately been amusing themselves more than usual in the ordinary practice with football, in the Barrack-square, and a healthful exercise is foot-ball.”

The wording “more than usual” suggests football might have been played by soldiers in the past. But was there something special about this game? It appears so, because it was covered by all three of Sydney’s newspapers within a day of each other.

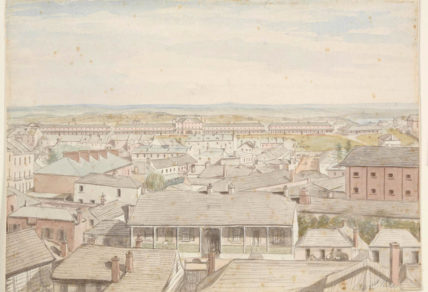

George St, Barracks, 1842. Picture by John Rae. Credit: Dixson Galleries, State Library of New South Wales

The Sydney Monitor described the event thusly:

“The privates in the barracks are in the habit of amusing themselves with the game of foot-ball; the ball may be daily descried repeatedly mounting higher or lower, according to the skill and energy of the military kickers thereof.”

What type of football were they playing? The description suggests a kicking (as opposed to running) game, and the “higher or lower, according to the skill” could be a reference to punt kicking.

And just who were these soldier-footballers? The Sydney Gazette noted that “The 57th and the 39th are Irish regiments.”

Irish? I was drawn to an article published by the Belfast Media Group in 2013 on research carried out by John Lynch, an Irish historian. Lynch said that “Between 1830-1878 on average the Irish made up 28 per cent of the [British] army.”

The incentive for an Irishman to enlist was a basic one – they “were given clothes and three meals a day.” What’s more, the Irish soldiers never served in Ireland but were sent away to colonies in the West Indies, and no doubt, New South Wales.

The 57th and 39th regiments served in Ireland for six years prior to being despatched to New South Wales – enough time to recruit a fair percentage of Irish privates. The Hobart Town Gazette in 1826 informed its readers that “The remainder of the 39th has marched to Cork, for the purpose of embarking in transports for New South Wales.”

Our pioneering 1829 football article in the Sydney Gazette mentioned these soldiers were playing their “native game.” The native game of Ireland? Were these soldiers playing a form of Gaelic football?

In 1832, an indignant church-goer wrote a letter to the Sydney Herald:

“Last Sunday, during Divine Service, a large batch of youngsters were eagerly engaged in playing at foot-ball in Hyde Park. Have they [the police] no power to prevent the disgraceful pitched battles that take place weekly in the neighbourhood;”

It sounds like those early games were rough. And Sydney was a rough place. In 1820, almost 40 per cent of the white population were convicts and the colony was still receiving convicts until 1840.

I wonder what those convict-era footballers were thinking when they fronted up to Mrs Hordern’s store in King Street in December 1838. Mrs Hordern was the first retailer to advertise foot-balls for sale and even suggested they would make good Christmas gifts.

Perhaps using one of Mrs Hordern’s foot-balls, a group of Irishmen were recorded playing football in Hyde Park in 1840. The game was just as rough as it had ever been. The occasion was the Queen’s Birthday holiday and it was described in the Sydney Herald:

“A number of Irishmen assembled in Hyde Park to give the Colonists a specimen of the game of hurling, which as usual, terminated in a row. There was also a game of football attempted which also gave rise to sundry scuffles and broken shins to boot.”

Through the 1840s, football in Sydney was played on festival days or notable public holidays. For instance, on the Queen’s Birthday in 1846, celebrations among the military included a blindfold wheelbarrow race and a game of football between the grenadier and light companies.

On Boxing Day, 1849, there was a sports day at Penrith Racecourse. According to Bell’s Life in Sydney and Sporting Reviewer, the day featured horse racing, a cricket match, and “a match at football between ten crack players.”

On the verge of the gold rush era, football seemed to take a hiatus in Sydney. It is worthwhile then, turning our attention to other parts of Australia.

Close up of an illustration of a festival day at Balmoral, Sydney, 1870, showing people playing football. From the Illustrated Sydney News. (Credit: Trove, National Library of Australia)

European settlement in Tasmania began in 1803-04 with the establishment of convict settlements at Hobart and on the Tamar River near modern-day Launceston.

In 1836, the government considered selling the public land in Hobart known as the Government Domain. The Hobart Town Courier railed against the sale:

“Where else are our young men to breathe fresh air and recreate from the indoor toil of a long day? Do you interdict cricket, foot ball, golf, and all other outdoor and national amusements?”

So there is a suggestion that football was played in the Government Domain in Hobart. But are there more concrete examples?

An article from the Cornwall Chronicle in 1840 looks promising:

“Thomas Marshall, who without doubt thought himself a humorous customer, was charged with killing time in the pleasing recreation of football, using the ribs and trucks of Henry Boyle, for that purpose, who grievously complained of the sensation he experienced.”

Ouch! That’s not quite the reference I was after – although I’m pleased to report Tom Marshall was fined five shillings for his red card worthy offence.

Like in Sydney, football was played on holidays and days of celebration. The Courier, in early 1848, noted that the patrons at the Tee-Totallers annual festival “danced on the green to the music of the band; while the more masculine engaged in playing at foot-ball and other old English sports.”

At the Catholic Tee-Total society gathering on Boxing Day 1848, the Hobarton Guardian reported the amusements included “dancing, hurling, foot-ball,” and, just in case that didn’t catch your fancy, “running for a pig.”

By 1866, football in Tasmania had become more organised when the first clubs were formed: New Town FC and Hobart Town FC in the south, Launceston FC in the north. The first match played between club sides was on the 26 July 1866 when G. Wright kicked New Town’s only goal in a 1-0 victory over Hobart Town.

The match was played on the Government Domain, which had not been sold off after all.

Football came to South Australia just a few years after Europeans arrived in 1836. A newspaper report in the South Australian Register in 1843 referred to Irish colonists celebrating St Patrick’s Day:

“Yesterday, being St Patrick’s Day, the natives of the Emerald Isle kept their usual anniversary by a game of football in the neighbourhood of the City Market, Thebarton, after which an ox was roasted whole.”

I’m not sure how the night ended up, but the Register went on to say that “they regaled themselves and their families in genuine Irish style.”

A football club was formed in 1860, only a year after the first club in Melbourne. Known as the Adelaide Football Club, the members met on the North Adelaide Park Lands and formed sides according to whether they lived north or south of the River Torrens.

The matches continued throughout the 1860s with increasing patronage. Soon the teams had developed uniforms of sorts: North playing in blue caps and South in pink. Blue and pink flags were hung from the goalposts. Large crowds turned up and it was a place to be seen. Among the spectators were the cream of Adelaide society, including such dignitaries as William Younghusband, the Governor of South Australia.

Football had a carnival-like atmosphere and games were often accompanied by music. The South Australian Register in 1860 stated that “during the afternoon, Schraeder’s brass band played some enlivening airs and contributed to the gayness of the scene.”

The Port Adelaide Football Club was formed in 1870 and still exists as an AFL (and SANFL) club. The need for a standard set of rules led to the establishment of the South Australian Football Association in 1877. The rules adopted were those of the Victorian football clubs. And it is to Victoria we now turn.

The Melbourne Cricket Ground in 1878, photographed by Charles Nettleton. (Public domain image)

In 1803, an attempt was made to start a convict settlement near modern day Melbourne. It was not a success. Some of the convicts, including one William Buckley, escaped. The settlement was moved to Tasmania instead.

When the first permanent European settlers arrived back in the Melbourne area in 1835, they were met by a large group of Indigenous Australians. In the group was a shaggy-haired white man. It was none other than William Buckley, a man who no-one had given a chance to still be alive after 32 years.

No-one would have given Melbourne ‘Buckley’s chance’ of having a population of half a million and its very own football code just 25 years later.

The first account of a football match I came across was advertised in the Melbourne Daily News on 29 March, 1850. It was a day that promised a “Grand foot-ball match for a silver watch.” If football wasn’t your thing you could witness Australia’s only German-born conjurer, Monsieur Festot, perform his “celebrated trick of hatching eggs in a bag.”

In November 1850, Melbournians were in party mode. The occasion was the passing of a bill in British Parliament creating the new colony of Victoria, which until that stage had been part of New South Wales. Four days were given over to Separation celebrations.

The climax to this celebration of Victorian-ness was a game of football – washed down with “a supply of beer for the million on the ground.”

In the night, houses all over Melbourne were illuminated; “even the most dirty hovels in the most dirty of all the dirty lanes in the city” according to the Age. There were bonfires, fireworks and rockets, tar barrels were set on fire in open spaces, and from all over the city ‘reports of firearms resounded for some hours.’

A gymnastics day was held on the last day of festivities. There was a programme of old English sports, which included climbing a greasy pole to reach a top hat with a prize of £1 in it, and chasing a pig with a greasy tail, where the prize was the pig. The last event of the day was a 12-a-side game of foot-ball, won easily by a team led by a Mr Barry.

It is noteworthy that the climax to this celebration of Victorian-ness was a game of football – washed down with “a supply of beer for the million on the ground.”

Just a year after the separation festivities, Melbourne had become one of the world’s biggest boomtowns. The discovery of gold near Ballarat and Bendigo triggered a gold rush that increased the population of Victoria from 80,000 to 540,000 in just ten years.

After the easily won alluvial gold began to run out, many of the new arrivals drifted back to Melbourne.

In 1857, an event in the world of literature had a far-reaching impact on the popularity of football. It was the publication of Tom Brown’s School Days by Thomas Hughes. The book, about a boy from the prestigious Rugby School in England, was a best-seller throughout the English-speaking world. With depictions of football as played at Rugby School, and its emphasis on manly, physical sports, it would have struck a chord with young men across Australia, including Melbourne, bursting at the seams with young men back from the goldfields.

When describing the appeal of football to its readers, the Argus newspaper said, “Let those who fancy there is little in the game, read the account of one of the rugby matches which is detailed in that most readable work, ‘Tom Brown’s School Days,’ and they will speedily alter their opinion.”

No doubt Tom Wills from Melbourne would have read it. Wills, a football enthusiast and a more than handy cricketer, had attended Rugby School as a youngster. At one stage he captained the school’s cricket team.

In 1858, when Tom Brown’s School Days was running off bookshelves across the country, Wills composed a letter to a newspaper.

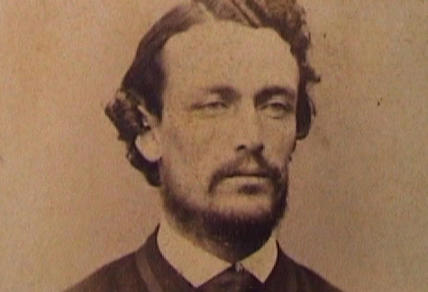

Tom Wills c. 1863. (Public domain image)

It says something about our culture that two of the most famous letters of Australian literature are from an outlaw (Ned Kelly’s ‘Jerilderie Letter’,) and another urging Australians to take up a sport.

Wills’ letter exhorting Victorian cricketers to form a football club was published in Bells Life in Victoria and Sporting Chronicle, on 10 July 1858, under the heading ‘Winter Practice’. It was an attempt to help Victoria’s cricketers keep trim in the winter months. Wills didn’t hold back with the language. He decried the cricketers who were “inclined to become stout and having their joints encased in superabundant flesh.”

To be honest, Tom Wills’ exhortations were almost half-hearted. He even gave the cricketers a choice. If they weren’t interested in football, Wills suggested they should at least form a rifle club. This had the added advantage of preparing cricketers in case “they may be some day called upon to aid their adopted land against a tyrant’s band.”

Wills signed off by saying that he hoped the cricketers “formed either of the above clubs,” and for good measure, “or, at any rate, some athletic games. I remain, yours truly, T.W. WILLS.”

But the cricketers chose footballs over rifles and preparations were made for the playing of some games, the first of which was a series of three matches between the students of Melbourne Grammar and Scotch College. They were played in the Richmond Paddock, with Tom Wills one of the referees.

The next year, 1859, the Melbourne Football Club became the first football club to be formed in Australia and a set of rules was drawn up. Tom Wills was instrumental in all these early developments. The new sport of Australian football had been born, and the rest, as they say, is history.

According to historian Tony Collins in his book, The Oval World: A Global History of Rugby, Australian football was ‘the first type of football to become a mass spectator sport anywhere in the world.’

The excitement created by football in Victoria spread to other parts of Australia. Even Sydney’s lethargic footballers were getting itchy feet.

When Sydney’s winter sportsmen awoke from their slumber in 1865, much had changed in the football landscape. Tom Brown’s School Days had been released, the sport of Australian football had been established, and in England, a schism had occurred that led to the creation of the Football Association in London. The first rules of association football, or soccer, were published in 1863.

The members of Sydney’s first football clubs now had a choice between three rule sets. The first club, the Sydney Football Club, was formed at a meeting in a sports store called Lawrence’s Cricket Depot on 30 May, 1865. It is thought that the rules they chose were the ‘Laws of Football as played at Rugby’ which had appeared in the 1863 yearbook of the Albert Cricket Club, a club to which many of the Sydney players belonged.

Also in 1865, the Australian Cricket Club formed a football team and the two sides began playing games in Hyde Park. These are regarded as being the first club rugby matches played in Australia.

Later in 1865, Sydney FC played a new opponent – Sydney University. This was the first newspaper mention of University playing the game. And this is where things get murky. On the badge of a Sydney University jersey, it says 1863, yet contemporary articles clearly state that the Sydney Football Club of 1865 was the first football club in Sydney. Perhaps no-one will ever know the true story.

In the following year, the Sydney Football Club announced they were going to play under Victorian rules. They played matches against the Australian Club, which often ended acrimoniously. University was the sole torchbearer for rugby until 1870, when Wallaroo, a club with a strong rugby ethos, was formed.

In 1865, the Australian Cricket Club formed a football team and the two sides began playing games in Hyde Park. These are regarded as being the first club rugby matches played in Australia.

Sydney’s dalliance with the Victorian game was not over. And it was a desire to see an intercolonial football contest that nearly tipped the balance against rugby.

Redfern Oval, just a long punt kick from the city of Sydney proper, is synonymous with the sport of rugby league. Many still regard it as the spiritual home of the NRL’s South Sydney Rabbitohs.

But 140 years ago, the place went by a different name: the Albert Ground. During the winter of 1877, it was the scene of two of the more intriguing games in Australia’s football history.

The first match, on 23 June 1877, was a game of rugby featuring the Waratah club from Sydney. Nothing unusual about that. Their opponent, however, was the Carlton Football Club from Melbourne.

The following week the two teams met under the rules of Victorian football. Not surprisingly, Waratah won the rugby match and Carlton won the Victorian rules match.

The games were well attended and demonstrated that not only had Sydney’s sporting public and players enjoyed an inter-colonial contest, but they had developed a taste for the Victorian game.

These games directly led to the formation of the New South Wales Football Association (playing Victorian rules) in 1880, and the loyalty of Sydney’s sports fans hung in the balance.

It wasn’t until 1882, when New South Wales began playing inter-colonial rugby matches against Queensland, that rugby established its preeminence among the football codes of New South Wales.

On 20 January 1849, a challenge in the form of an advertisement in the Moreton Bay Courier was issued to “The Sporting Blades of Brisbane” from “The Lads of Kangaroo Point.” They let it be known they would “challenge all-comers to a game of Foot Ball.” I couldn’t determine if any blades took up the lads’ challenge but it does show that football in Brisbane goes back a long way.

For a state so historically strong in the rugby codes, it comes as a surprise that Queensland was originally an Australian football state. The Brisbane Football Club was founded in 1866 using the Victorian rules that were widely published at the time. The dominance of Australian football was first challenged in 1876 when the Rangers club was established under rugby rules.

Adding to the confusion, in the same year, the Petrie Terrace Football Club was formed under association football rules – making it probably the earliest association football club in Australia. Petrie Terrace FC proved short-lived, though. It changed its name to Bonnet Rouge and switched to rugby.

Rugby struggled to gain a foothold and the clubs switched back to Australian football before playing both it and rugby in the same season. But in 1883, another footballing challenge was issued in Queensland. This time it was the rugby players of New South Wales who accepted. The first inter-colonial game of rugby held in Queensland was played at Eagle Farm racecourse and was a 12-11 win for the home side.

Buoyed by the success of the inter-colonial match, a rugby association known as the Northern Rugby Union was established, eventually becoming the Queensland Rugby Union in 1893.

Where does the sport of association football fit into this story? It is commonly held that the first game of association football in Australia was between the Wanderers club of Sydney and a team from The King’s School, Parramatta. It was played at the school on 14 August 1880 and won 5-0 by the Wanderers. But association football-like games were played earlier than this.

In 1879, the Cricketer’s Club of Hobart was formed as an association football club. In the Cornwall Chronicle, Captain Boddam even took a swipe at the Victorian game “which was not football but more the handball played by girls at school.”

When football clubs with different rules played against each other, the accepted practice was for the home club’s rules to apply. So it was that on 6 June 1879, the first match under association football rules in Tasmania took place when Cricketer’s FC hosted New Town FC and played out a 0-0 draw.

When football clubs with different rules played against each other, the accepted practice was for the home club’s rules to apply.

An association football match of sorts was played in Brisbane in 1875 between Brisbane FC and the inmates and wardens of the Woogaroo Asylum. Notably, the rules were altered so that “the ball should not be handled nor carried.” It was a kicking-only game of football but still rough as hell; several players were “denuded of their upper garments.”

In the remarkable football season in South Australia in 1873, the clubs originally agreed to play by the rules of the English Football Association. The first game under these rules was between Port Adelaide and Kensington, on 5 July 1873.

Kensington won the match 1-0; the goal was a free kick by F. Perry, which controversially deflected off the crossbar (which wouldn’t have counted under the old rules). Port Adelaide are not only one of the oldest Australian Football clubs in the country but could have a claim on being one of the oldest association football clubs as well.

On 5 June 1869, the Newcastle Chronicle announced that a football match would be played: “This is, we believe, the first football match that has ever taken place in Newcastle.”

The game was played by a team of 11 against a team of eight; far less than the 15 to 20-a-side games of football played elsewhere. Another game – this one a ten-a-side version – was reported the following week. What code was it? It is hard to be certain from the reports. A potential match winning goal was disallowed for going ‘over’ the goal.

In 1869, when Sydney University was left with no local teams to play, the students played two football matches against the crew of HMS Rosario, freshly back from intercepting a blackbirding shipment of Pacific Islanders bound for the Queensland cane fields. The games were played in the Domain, not far from the Botanic Gardens, and within sight of the ship moored in Farm Cove.

A football game in Victoria c.1890 featuring goals with what looks to be a crossbar. (Credit: State Library of Victoria)

Big crowds turned out, including women watching from the balconies of the fashionable houses in Macquarie Street. According to Bell’s Life and Sporting Chronicle, in the first match, the Rosario players’ understanding of the rules “directly opposed many of the rules under which the University usually play, the latter adhering closely to the rugby code.”

In the return match, “a capital kick by one of the seamen sent the ball straight between the University goal posts, but just above the bar.” Later in the game, “the ball was twice kicked between the Rosario’s goal posts, but above the bar. The game eventually concluded without either side obtaining a goal.”

In this second match, a score had to be made under the bar; definitely not the standard rugby practice of kicking over the bar.

Even as far back as 1859 in Melbourne, on the eve of the formation of the Melbourne Football club, rules of games were still murky. In the first match of the season, Bell’s Life in Victoria and Sporting Chronicle reported that “some of the parties engaged following out the practice of catching and holding the ball, while others strenuously objected to it, contending that the ball should never be lifted from the ground otherwise than by foot.”

So it seems that predominantly kicking games have been around since even before Mrs Hordern started selling footballs for Christmas.

There is much common language in the reports of early football in Australia. Scoring was always by means of kicking the ball through goal posts, with or without a crossbar. Even in rugby, scoring was by a goal kicked from the field or a ‘try for goal’ after a touch-down (think modern day conversion).

Teams usually changed ends after a score and matches were almost always low scoring. Some degree of handling was common; even the first rules of association football in 1863 allowed for a ‘fair catch’ or mark, but you could not handle a ball on the ground.

When reading these accounts, it is never completely clear what type of football is being played. Is it rugby, Australian football or association football that the reporter is describing? Perhaps a game could have elements of all three. It is hardly surprising that there were frequent disputes over the rules.

For casual spectators in those days, all football matches probably looked the same with their ‘goals’, ‘scrimmages’, and everybody’s favourite, ‘spills.’ Pinning down precisely when one code begins is difficult. The origins of Australia’s football codes are murky indeed.

Wynyard Park in Sydney’s CBD. The birthplace of Australia’s football codes? (Image: Paul Nicholls)

It’s been some journey. From chasing squealing pigs to shimmying up greasy poles for a hatful of cash. From a letter fat-shaming Melbourne’s cricketers into taking up football to poor Henry Boyle getting the shit kicked out of him in a back lane of Old Hobart Town. We’ve heard Schraeder’s brass band entertaining patrons in Adelaide and watched in trepidation as Brisbane’s footballers took on the half naked inmates of Woogaroo Asylum. We’ve had rowdy footballers in Hyde Park disturbing churchgoers, and, finally, to red-coated soldiers playing a sport perhaps resembling Gaelic football, in the military barracks in Sydney.

Which brings me to the reason I’m here at Wynyard Park. Walking south for another block yields a clue. You come to a street running east-west that intersects George Street not far from Martin Place. This is Barrack Street – named for the huge military compound that once stood here.

A thick wall, ten feet high, enclosed the area bounded by Barrack, George, Margaret and Clarence Streets. The wall, built with convict labour in Governor Macquarie’s time, was at once a means of fortification and a psychological barrier isolating the military from the civilian population. Macquarie had good reason to be wary of soldiers involving themselves in civilian affairs. It was from this very barracks that Australia’s one and only military coup was launched in 1808, overthrowing the governor, William Bligh.

The open space at Wynyard Park is essentially a remnant of the parade ground of the old military barracks. It is a space shared in spirit by all of Australia’s football codes. If I was to build an altar to football here, where would I put it? There’s a statue of politician John Dunmore Lang in a likely spot.

Perhaps it was near here that privates from the barracks were first observed playing at foot-ball by reporters from three Sydney newspapers on a winter’s day in 1829. It seems as good a place as any.

Considering the murky origins of Australia’s football codes, it’s only fitting that JD Lang has a pigeon on his head.

Written by Paul Nicholls.

Paul is a Sydney-based writer with a particular interest in the history and culture of sport. He originally wrote a number of long essays on The Roar under the pen name, 70s Mo. You can follow him on Twitter @70s_Mo.

Editing and layout by Daniel Jeffrey

Lead image and image of Richmond Paddock are both credit State Library of Victoria.

Wide images of Carlton vs Waratah football match and Balmoral festival are both credit Trove, National Library of Australia.