As the Wallabies and All Blacks prepare for their first encounter of 2017, let us look back at some of the great matches between these two rugby nations.

There is no shortage of memorable Bledisloe Cup encounters – hardly surprising given that 86 years have passed since the famous trophy was first awarded. But it is fitting to start with a match considered to be one of the finest played in international rugby history, one that merited a truly memorable description…

Bledisloe Cup sex

In 2000, the Wallabies and the All Blacks played one of the greatest Tests in the history of rugby. In front of over 100,000 people crammed into the Olympic Stadium, in a festival of brilliant performances, comebacks from defeat by both teams and a climactic finish, the All Blacks, through a last-minute try scored by the iconic Jonah Lomu, won 39-35.

This remains the most points scored in a Test between Australia and New Zealand. The match so enthralled the general public that the journalist Jane Fraser revealed to her readers that eastern suburbs matrons had taken to calling great love-making the equivalent of “Bledisloe Cup sex.”

Should Lord Bledisloe have his name on the cup?

There is an irony in the iconic name given to the trophy played for by Australia and New Zealand in Test rugby.

There is no evidence that Lord Bledisloe, the Governor-General of New Zealand between 1929 and 1935 and alleged donor of the Bledisloe Cup, knew one end of a rugby ball from the other or cared in any way at all about the Tests played under his nomenclature.

Who was this Lord Bledisloe who has such an undeserved sporting immortality?

When I worked at the Sydney Morning Herald, in the days when it had a remarkable library holding documents going back to 1842, I discovered in this archive a typewritten biography of Lord Bledisloe, The English Statesman, that was sent out to newspaper offices throughout the British Empire by the Whitehall press office in London, dated October 1929, to mark his New Zealand appointment:

“Charles Bathurst, barrister, politician, agriculturalist and First Baron BLEDISLOE, was born Sept. 1867, and educated at Sherborne, Eton and University College, Oxford. After leaving Oxford, he was called to the bar in 1894 and practised as a Chancery barrister and conveyancer for 16 years. In 1910 he was elected Conservative MP for S. Wilts and made a member of the Duchy of Lancaster …”

This biography was updated in March 1934 when Lord Bledisloe was coming to the end of his term as Governor-General:

“In November 1929, Lord Bledisloe was appointed Governor-General of New Zealand… His knowledge of and interest in agriculture made him the most popular Governor of the Dominion in many years. He did everything in his power to strengthen the Empire bond in New Zealand. The fact that every article he wore was made there from Dominion materials gave great satisfaction… In May, 1932, he and Lady Bledisloe presented to the people of New Zealand one of the country’s most precious relics… a house built by James Busby… at the Bay of Islands, outside which the Treaty of Waitangi was signed in 1840…”

There is no evidence that Lord Bledisloe, the alleged donor of the Bledisloe Cup, knew one end of a rugby ball from the other.

There was no reference in this official retrospective of Lord Bledisloe’s term of office in New Zealand of the famous trophy he was supposed to have donated for competition between the national rugby teams of New Zealand and Australia.

Enter now into this strange story Bruce Hewitt, a New Zealand-born journalist and rugby fanatic, who worked for the New Zealand Press Association in New Zealand and Australia during a distinguished career in the media.

An article Hewitt wrote for the Sun-Herald in 1988 gave an entirely different perspective on the so-called “most popular Governor.” Hewitt remembered Lord Bledisloe as a man, often at odds with journalists, “who had little interest in football, and his outdoor activities were limited to farming and long-winded speech-making at country shows.”

Lord Bledisloe was once photographed, Hewitt recalled, at the Canterbury Show at Christchurch. The next day the photograph of a beaming Lord Bledisloe was run in the Christchurch Times. The caption underneath the photograph described Lord Bledisloe “as the prize-winning ram at the Canterbury Show.”

Lord Bledisloe insisted that the sub who wrote the caption be dismissed.

This incident, wrote Hewitt, triggered Lord Bledisloe’s “long-running differences with the New Zealand press… To a generation of reporters he became ‘Chattering Charlie,’ and there were harsher names when his complaints led inevitably to sackings in those bleak, jobless, and depression days.”

An official of Lord Bledisloe’s stature who is offside with the national press is in clear need of a public relations gesture, or gestures, it seems to me, to persuade the public that he is a man of compassion and devotion to the New Zealand people.

The gift of Waitangi House, mentioned in the 1934 Whitehall press release, fitted this need. And so too did giving his name to a Test match competition between the rugby teams of Australia and New Zealand.

An observant reader will notice that the inference in the last sentence is that Lord Bledisloe did not actually donate the Bledisloe Cup, as popular memory indicates.

But he did allow his name to be used with the trophy, which is an important difference.

The fact is that there was no acknowledgement by Lord Bledisloe of any deep involvement or even interest in the trophy. There is no evidence, either, that Lord Bledisloe instigated the creation of the trophy.

There was no mention, as I have noted, in the official biography issued to the media at the end of his term of office in New Zealand about the Bledisloe Cup, either.

Lord Bledisloe at the end of his tenure in New Zealand. (Archives New Zealand/Flickr CC BY-SA 2.0)

With the Bledisloe Cup Tests already being played and the large trophy on display at these matches while Lord Bledisloe was still in office, you would have thought that the trophy’s creation would have been listed as one of his achievements in New Zealand.

Years later, too, when Lord Bledisloe, now in his anecdotage and sounding like PG Wodehouse’s Lord Emsworth with his passion for pigs, toured New Zealand and Australia in the 1950s, there is no mention in the numerous press articles of the time of his connection with the rugby trophy named after him.

The official version of his close involvement is given in Keith Quinn’s The Encyclopedia of World Rugby:

“The Bledisloe Cup was presented in 1931 by Lord Bledisloe, then Governor-General of New Zealand, as a trophy to be played between the Test teams of Australia and New Zealand… The first game for the trophy was played at Eden Park in Auckland in 1931, New Zealand winning by 20-13. The game, played in front of Lord Bledisloe, was notable for the small crowd that turned out (nearly 15,000) and for the scoring of 14 points by the New Zealand fullback, Ron Bush of Otago…”

But did Lord Bledisloe watch the match at Eden Park? The evidence is strong that he did not.

Gordon Slater in his monumental history, On the Ball: The Centennial Book of New Zealand Rugby, is adamant that Lord Bledisloe was not even in Auckland at the time: “He was in Wellington to attend the commercial travellers’ smoke concert, at which he told them that the world was topsy-turvy, particularly in the sphere of industry and commerce.”

The 1931 match at Eden Park involved the first Australian side in 18 years to play a Test (according to the NZRU) in New Zealand. Public interest in the tour was lukewarm. The side had won three matches, lost four and drawn one in the lead-up to the Test.

We go back now to Gordon Slater:

“On the day before the game, it was announced from Wellington that the Governor-General had presented a cup for competition between New Zealand and Australian Rugby teams and that the first match for the trophy would be the Test at Auckland the following day. Mr S.S.M. Deans, president of the New Zealand Rugby Union, and T.C. Davis, manager of the Australian team, expressed appreciation of the offer. The design of the cup was to be decided upon later, but it would be symbolic of the two countries.”

Notice that the announcement was made from Wellington, not Auckland. This is another indicator that Lord Bledisloe remained in Wellington, despite the fact that New Zealand were playing Australia for a trophy that bore his name the next day in Auckland.

The four Tests against the British and Irish Lions in 1930 drew crowds of 27,000 at Dunedin, 30,000 at Christchurch, 40,000 at Eden Park in Auckland and 40,000 at Wellington. The problem for the NZRU was that Lions tours, like the successful Springboks tour of 1921, were once in a decade money-making events.

Sir Charles Bathurst Bledisloe, whose name adorns the Bledisloe Cup. (Public domain image)

The Wallabies, now that the QRU had been re-established in 1929 after closing down during World War I, would be touring New Zealand every couple of years. But on the evidence of the poor crowds for the first tour of the Wallabies since before World War I, the NZRU decided that something had to be done to make the New Zealand-Australia rugby contests more popular.

My hunch is that the NZRU decided to enhance the Tests by giving them a sort of Ranfurly Shield makeover.

In 1901, the Governor of New Zealand, Lord Ranfurly, offered a challenge trophy to the NZRU to be competed for between NZ unions, on a one-off basis, with the holder playing at home unless deciding to take the shield on tour.

By the 1930s, and even today, the Ranfurly Shield, the storied ‘Log of Wood,’ had created an aura and a passion about it that meant that big crowds invariably attended shield challenges.

An equivalent of a Ranfurly Shield for New Zealand – Australian Test competition was put in place by the NZRU to create interest in the trans-Tasman rugby rivalry.

Getting old ‘Chattering Charlie’ to agree to the concept, though, was easier than getting him to actually attend the first Bledisloe Cup Test.

“We’ve beaten the bastards! You beauty!”

Headlines in the sports section of the New Zealand Free Lance of 7 September 1949 summed up the anguish and shock of the New Zealand rugby community:

“AN ALL BLACK DAY IN RUGBY: TWO TEST DEFEATS. Penalties Give Springboks Win For Second Time, Australia Too Good For Uninspired Home Side”

On the same day, separated by thousands of miles and a few hours in time, the All Blacks lost two Tests. Bad (and in New Zealand eyes, biased) refereeing was behind a loss by a touring New Zealand side to South Africa 9-3 (three penalty goals to one try). Incompetent administration and hubris was to blame for a 11-6 defeat of another New Zealand side at Wellington by a touring Australian side.

With 30 of the nation’s best players touring South Africa, the NZRU was careless about the prestige of the All Blacks, and condescending of Australian rugby, in agreeing to a two-match Test series for the Bledisloe Cup.

There was an excuse, perhaps, for the carelessness. From 1931 up to 1949, 14 Bledisloe Cup Tests had been played. The Wallabies had won one and drawn one in 1934 to win their first home Bledisloe Cup series. In all, the Wallabies had lost 12 Tests, including all four played in New Zealand in the two-match series in 1936 and 1946.

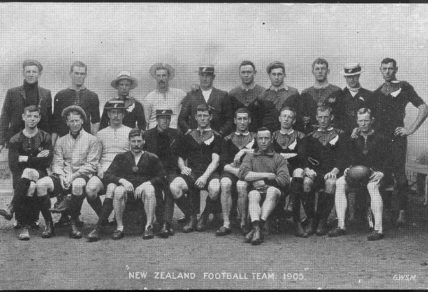

The precedent, too, for playing a third-string side had been set in 1905 when New Zealand defeated Australia 14-3 at Dunedin while the famous 1905-06 All Blacks had already left the country on their epic tour of Britain and France.

The 1905-06 touring side (shown above) led to a weaker All Blacks team being played against the Wallabies. (Public Domain Image)

The task of the third-string All Blacks in 1949 was made much harder by the fact the team for the first Test at Wellington was selected only the day before it ran on to the field. No coach was provided, either.

The All Blacks were outplayed by the Wallabies, who tailored their tactics to suit a chilly, blustery day. Trevor Allan, the Australian captain, won the toss and played with the wind. By half-time, the Wallabies were leading 11-0 after kicking for position when they had the ball.

The All Blacks’ possession was spoilt, particularly at the lineout, by the ‘impetuous’ Wallaby flanker David Brockhoff and the greyhound-fast Col Windon launching themselves at the New Zealand number ten, legally, when the half-back was set to pass to him.

This relentless attack on the New Zealand pivot destroyed any cohesion the All Blacks might have mustered.

Years later, the inimitable Brockhoff, who attracted calls of “Off-Side Brockhoff!” throughout the tour, summed up the havoc he and Windon had caused this way: “We missiled them all day, never gave them a sniff.”

The mayhem of the Brockhoff-Windon double act continued during the second Test at Eden Park, won comfortably by the Wallabies 16-9.

The victory secured Australia’s first Bledisloe Cup series win in New Zealand.

“Brockhoff’s spoiling and scavenging were reminiscent of Cliff Porter and Dave Gallaher at their best,” RH Chester and NAC McMillan noted in their monumental history of All Blacks rugby Men in Black.

The Wallabies were able to dominate the lineouts, a rare achievement in this era, with Nick Shehadie, later Lord Mayor of Sydney and knighted for his civic achievements, and a brash young Rex Mossop applying the needed energy and grunt.

“Hi Dad, hi Mum, hi Kirk! We’ve beaten the bastards! You beauty!”

At the end of the Test, an elated Mossop gave some indication of the uninhibited sports broadcaster he was to become after his distinguished rugby and rugby league career ended when he was asked by a radio reporter to send a cheerio call back to Australia. Without any hesitation, he grabbed the microphone and yelled out: “Hi Dad, hi Mum, hi Kirk! We’ve beaten the bastards! You beauty!”

There was one further humiliation in store for New Zealand rugby in a year when the All Blacks lost four Tests to the Springboks, and two more and the Bledisloe Cup to the Wallabies.

Peter Jenkins, in his magisterial history Wallaby Gold, tells the story of how the tour manager of the 1949 Wallabies, Bill Cerutti, rubbed salt into New Zealand rugby’s wounds:

“The All Blacks heading home from South Africa docked in Sydney en route to New Zealand. When they arrived, Cerutti was down at the wharf, brandishing the Bledisloe Cup. It was the first time Australia had won the silverware in 15 years. ‘Here it is,’ he shouted to the New Zealanders. ‘We’ve got it now.’”

The Bledisloe Cup goes missing on duty in Melbourne

Two years later, the Bledisloe Cup was taken back by the All Blacks in a three-Test series played in Australia with the All Blacks, determined on revenge, winning all three Tests.

From 1951 to 1978, the All Blacks won 26 Bledisloe Cup Tests and all 12 series. The Wallabies won only five Tests and two were drawn.

The effect of this one-sided contest was the interest in the trophy itself diminished.

The All Blacks’ tradition, for instance, of filling the huge trophy to the brim with 26 jugs of beer and skulling the lot after a winning series was forgotten, only to be revived decades later in the professional era.

The real clincher in how unimportant the Bledisloe Cup had become in the memory of the rugby community is that it actually disappeared for a number of years. Apparently no-one, either in New Zealand or Australia, was aware of this disappearance, nor was anyone concerned about it.

Bruce Hewitt was given the job of finding the Cup as part of his NZPA duties in Australia. After an intensive investigation, he was able to report back with good news:

“The Bledisloe Cup has turned up eventually unharmed under a great deal of dusty cardboard cut-outs of Maori huts and Mount Cooks in the back storerooms of the old New Zealand Government Tourist Bureau in Temple Court, Melbourne, where it had evidently been taken for display purposes and forgotten.”

The great ‘Brock’ restores the magic of the Bledisloe Cup

The first rugby article I wrote for the Sydney Morning Herald in the early 1980s gave a detailed analysis between the New Zealand obsession with dominating the advantage line compared with the Australian obsession with back play.

The next day, my phone rang.

“Brock speaking,” the voice at the other end of the line announced.

This was my introduction to John David ‘Brock’ Brockhoff. It is safe to say that no-one anywhere or at any time loved rugby – every aspect about rugby – more than Brock. No one gave so much back to the game as a player, coach, and supporter than he did. He even went to the airport in his later years to farewell and greet every Waratahs and Wallabies side leaving Sydney for a match somewhere in Australia or anywhere else in the world.

He talked about rugby with a passion and intensity unequalled by anyone I have ever come across.

On that first phone call, for instance, Brock quickly worked out that I was steeped in the New Zealand rugby tradition, developed by the Cavanaghs, father and son in Dunedin, of keeping the ball over the advantage line at all times, of quick rucks, low body height going into rucks and mauls, of driving hard through the middle of the field with a big inside centre and then playing the side of the ruck where the opposition had the fewer players. The Cavanagh system, too, called for relentless pressure on defence.

Brock immediately invited me to talk with a group of influential good old boys, including Sir Nicholas Shehadie, who would regularly sit at a long table at a Mosman pub where we would discuss our thoughts on the latest issues facing rugby, on and off the field.

David Lord, who knew Brock well, wrote a splendid tribute to the great man on The Roar marking his death: “Vale John David Brockhoff, one of rugby union’s finest”.

David Brockhoff regularly greeted the Wallabies at Sydney Airport after his playing and coaching days. (AAP Image/Sergio Dionisio)

He pointed out that when Brock took over as coach of the Wallabies in 1974, the national rugby side had lost 26 of their last 33 Tests, with two drawn.

The renaissance of the ‘Woeful Wallabies’ started with the Brockhoff side winning their two-Test series against England.

“The Wallabies were no longer in the international wilderness, and it was ‘Brock’ who led the way out of the tunnel into the light,” wrote Lord.

There was intense criticism of the ‘get-your-retaliation-in-first’ methods used by the Wallabies in these Tests from the British rugby media.

We can get a sense of the way Brock went about encouraging his players from this comment on The Roar from ‘cookie’ in response to David Lord’s tribute:

“My first memory of ‘Brock’ was when I was a school at Scots and he came to help coach some sessions. He had his trademark towel around his neck and being the first time I’d ever seen I thought, ‘Who the hell is this?’ His passion rubbed off on every lad but especially the forwards. I clearly remember his obsession with body height around the rucks and mauls, barking out order that reverberated around the ground.”

Brock was not for turning in his belief that the Wallabies could only compete successfully in Test rugby, especially against the All Blacks, if they contested and won the rucks and were as physical in attack and defence as the New Zealanders were during every minute of every game.

He was dropped as the coach of the Wallabies in 1976 but was brought back, controversially, for a one-off Bledisloe Cup Test to be played at Sydney in 1979.

Brock made further controversy by selecting a small but fiery flanker, Andy Stewart, to disrupt every attempt by the All Black backs to initiate passing movements. Stewart, quite literally with his low, diving tackles, put his body on the line at the rucks.

Tony Melrose, a gifted 19-year-old number ten with a shrewd and often prodigious punting game, was selected, like Stewart, to play his first Test against the battle-hardened All Blacks.

We don’t know what Brock told his Wallabies before they ran out on to the SCG for the Test. But it surely went something like this impassioned rant delivered to a Sydney University club side and remembered by a young Nick Farr-Jones:

No one gave so much back to the game as a player, coach, and supporter than Brockhoff did.

“You have to be everywhere breakaways. Everywhere! No excuses… Cause havoc at the breakdown like sharks in a school of mullets… And when you’re through the other side we’re like crows through the Opera House window. Get in, loot the joint and get out…”

In one period of the Test, won by the Wallabies 12-6, the home side inflicted the unprecedented humiliation on the All Blacks of winning 11 rucks and mauls in succession.

Sharks in a school of mullets could not have caused more havoc than Andy Stewart during this onslaught. Mark Loane made powerful, bullocking runs to unsettle the All Blacks at the edge of the rucks. Tony Melrose, playing with the coolness and accuracy of an old-timer, banged the ball inside the New Zealand 22 from all parts of the field to keep the All Blacks under constant pressure to get out of their red zone.

Andy Haden, the streetwise All Blacks second-rower, came up to Brock immediately after the Test and told him he’d “never been so tired in a match as in this one.”

“No Australian pack has taken so much ball in my memory off the All Blacks.”

Then Haden stripped off his jersey and handed it across to Brock in a tribute to a Wallaby coach who had successfully imposed the All Blacks pattern on New Zealand’s own national side.

With tears of joy in his eyes (“my cup was running over because we’d finally played a forward game at the Sydney Cricket Ground the way I wanted it played”), Brock joined the jubilant Wallaby team as it was carrying the massive Bledisloe Cup sedately around the ground.

Suddenly, on an impulse generated by a lifetime quest for the Holy Grail of a perfect Bledisloe Cup victory that had been fulfilled, he grabbed the trophy and raced like a Dervish around the SCG, followed by his players.

“Now I can live in peace”

The significance of the Brockhoff-coached, one-off Bledisloe Cup victory at the SCG in 1979 was that it was the first time the Wallabies had regained the trophy in Australia since 1934. It was also only the second win by the side in Australia against the All Blacks since 1932.

With that rugby Everest conquered, the next challenge was to win back the Bledisloe Cup in New Zealand, a feat only accomplished once, and against a third-string All Blacks side, in 1949.

Cometh the hour, cometh the man.

Alan Jones was a school teacher with academic qualifications from Oxford University, a highly-rated tennis player as a youngster, and later a speech writer for Prime Minister Malcolm Fraser (credited with giving his boss the line from GB Shaw’s Man and Superman that “Life is not meant to be easy …”). Later, he coached the Manly club side to a premiership victory over a dominant Randwick club team in 1983.

The next year, he was appointed the coach of the Wallabies, taking over from Bob Dwyer.

His team won 23 Tests out of 30, and four of the losses were by a single point, with three of these tight defeats coming against the All Blacks.

In 1986, with a singular Grand Slam in 1984 to his credit, Jones took the Wallabies to New Zealand with a single-minded determination to win back the Bledisloe Cup.

Alan Jones could be both charming and vitriolic. (Photo by S&G/PA Images via Getty Images)

Possessed of a strident opinion on virtually every matter that he was involved with, Jones could be charming (“the most approachable and articulated rugby person to visit Britain in the last 40 years as the coach of the Grand Slam 1984 Wallabies”) and vitriolic (“Campese played a horror of a game”) when the urge to either ingratiate or offend seized him.

The splenetic urge often seized him when things had not gone well with the Wallabies.

After the second Bledisloe Cup Test in 1984, when the Wallabies squandered a 12-0 lead at Ballymore to finally lose 19-15, I wrote an article for the Sydney Morning Herald arguing that his safety-first tactics were “paradoxically, a high risk way of winning the Test.”

I pointed out that the All Blacks had never come from being 12 points to nil behind in a Test and gone on to win. The Wallabies should have, I argued, tried to score more points when they were on top rather than play safety-first rugby by kicking the ball to the All Blacks, forcing them to make all the play.

The morning my article appeared in the Herald, the newspaper’s rugby writer, Jim Webster, came into the editorial writers’ room, placed his tape recorder on my desk and, with a smile on his face, pressed a button.

“Mate, you should listen to this.”

The tape recording started off with the opening moments of the press conference held by Jones to discuss the previous Test and the coming Test at the weekend. A journalist nervously asked Jones what he thought about the rugby article in the Sydney Morning Herald.

There was a moment’s silence on the tape. Then came Jones’ reply.

“That fellow with a name like a Russian wrestler? We take no notice of people like him.”

By the time the Wallabies started their tour of New Zealand in 1986, Jones had created a persona for himself and his Wallabies based on this style of highly personalised attacking rants against anyone or anything (the quality of the hotels the Wallabies were offered, for instance).

“That fellow with a name like a Russian wrestler? We take no notice of people like him.”

In turn, this Jones method created an atmosphere of fear and loathing for himself and his team.

Greg Growden, who was reporting on the tour for the Sydney Morning Herald, was hit by the persistence of the anti-Australia jokes on New Zealand radio talkback programs. It was as if the Wallabies coach had somehow poisoned the Australian-New Zealand rugby communities.

A certain loathing was directed even at Growden because he was in some way connected with the Wallabies, and, anyway, because he was an Australian.

On one occasion in a small New Zealand town, he approached a female bank teller.

“You an Australian?”

Growden replied: “That’s right.”

“I’m not serving you,” she replied. “I’m going to take my lunch now.”

The first Test at Athletic Park in Wellington was won by the Wallabies 13-12.

The second Test at Carisbrook Park, Dunedin, was lost controversially after a wrong decision by the Welsh referee, Derek Bevan, 13-12 by the Wallabies.

The third Test at Eden Park was game on for the series. The furore of speculation and angst in the New Zealand and Australian media was spectacular. Strangely, the main cause of the furore, Alan Jones, was the calmest person in New Zealand.

Greg Growden interviewed the Wallabies coach on the eve of the Test. He was reading David Stockman’s The Triumph of Politics and was confident of victory.

“There is a measure of arrogance in the team now,” he told Growden.

“There is a deep resentment and they felt denied after the second Test. It haunts them and this has to be purged. Still, they are relaxed about it. We have spoken so often.

“There is nothing left to do but win.”

The coaching instructions Alan Jones gave his Wallabies was to expect an opening onslaught and, when that was endured, to establish field position and strike with their faster outside backs from inside the New Zealand 22.

This game plan almost came unstuck when the ferocious opening All Blacks’ attack saw the powerful hooker Hika Reid storming towards the Wallabies try line. But before he could crash across for a try, he was confronted by the massive Topo Rodriquez. Smashing his shoulder into Reid’s ribcage, Rodriquez stopped Reid dead in his tracks and then drove him down into the turf like a pile-driver smashing in a post.

This was the moment the Test turned. The ferocious initial onslaught petered out. The All Blacks dug in sullenly and worked hard to keep the margin of their loss to 22-9.

I was at a rugby lunch some years later when Alan Jones peered into the dimmed lighting of the dining room from his speaker’s podium and said: “Stand up Enrique… He’s somewhere here today.”

And when the still burly, smiling Rodriquez stood up and raised his arms in triumph to the applause of the audience, Jones called out: “The man who made the tackle that saved the Bledisloe Cup for the All Blacks.”

In his biography, written with Jim Webster, For Love Not Money, Simon Poidevin described how sweet this particular victory was for the Wallabies:

“The dressing room was packed with people, there were television lights and photographic flashes, Jonesy was running around shouting hoarsely (who ever thought he’d be hoarse) that this was ‘bigger than Quo Vadis,’ we had our arms around each other, singing and congratulating ourselves, and every now and again you’d be passed the massive Bledisloe Cup, take a swig of champers from it, and pass it on… I remember Greg Growden from the Sydney Morning Herald asking me that afternoon in the Eden Park dressing-room what winning that 1986 series meant. I replied: ‘Now I can live in peace.’ It meant that much to me.”

There was a strange incident later that evening.

Players said they felt like collapsing at half-time, so frenetic had the pace of the game been. One revealed he began retching after a few lineouts.

The Wallabies were at an Auckland club indulging in a happy-hour before the official dinner. Then it was time to move the huge Bledisloe Cup into the dining room.

One of the players looked at the cup and said to Growden, who was busy taking notes for his article the next day in the Sun-Herald: “After that game you’ve got to be kidding. I wouldn’t be able to lift it.”

Other players told Growden how they felt like collapsing at half-time, so frenetic had the pace of the game been. One revealed he began retching after a few lineouts.

A reserve, Greg Burrows, took the wooden base of the Bledisloe Cup, another player took the silver top and, as Growden later reported, “since there was no one left, I had to carry the Cup. It was an eerie moment… walking through the club, cheered by hundreds of New Zealanders, when the Cup came into view, shaking it above my head, with everyone wondering who this unknown prima donna was in spectacles and a speckled suit. I wasn’t about to admit anything, relishing the moment while it lasted.”

There is a golden link between the wins by the Brockhoff Wallabies in 1979 at Sydney and the Jones Wallabies in 1986 at Auckland. In 1979, a run of 45 years of losses to the All Blacks in Australia was broken. In 1986, the Wallabies won a Bledisloe Cup series, the first time such a victory had been achieved in New Zealand in 39 years.

Never again could an Australian team go into a Bledisloe Cup Test and, despite the previous history of losses, not believe they could win.

George Gregan and his famous tackle

George Gregan, coming from nowhere, knocked the ball out of the hands of the All Black winger, Jeff Wilson, just as he was going to score the try that would have won the one-off Bledisloe Cup Test for New Zealand at the Sydney Football Stadium in 1994.

As in 1979, the Test was an Australian ambush that allowed the Wallabies to take back the Bledisloe Cup by winning a single match against the All Blacks with a 20-16 scoreline.

The handful of seconds embracing Wilson’s weaving run and Gregan’s thunderous hit on his diving body was the single most dramatic event in the entire sequence of Bledisloe Cup Tests.

Jeff Wilson, who was nicknamed ‘Goldie’ by his teammates for his prodigious sporting talents and his demeanour as a winner whatever the sporting occasion, beat four players in his run to the tryline. The failed defenders lay behind him as defeated as fallen trees. Wilson prudently switched the ball from his left hand to his right to plant it over the tryline. Then he launched himself into a triumphant dive.

And then came George Gregan and his famous tackle.

The tiny halfback smashed all his weight into Wilson’s back just as the try was being scored.

A series of photographs published in the Sydney Morning Herald the next morning showed All Black Shane Howarth’s yell of triumph turn into a rictus grin of disbelief and despair as the ball spilt clear of Wilson’s grasp.

George Gregan during the 1994 Bledisloe Test. (Photo by David Rogers/Getty Images)

Another photo reveals the blobs of the boots of Wallaby flanker David Wilson lying prone on the ground, one of the defenders Wilson had beaten with his swerves and sidesteps to the tryline.

Gregan’s arms are shown next in the photo sequence, encircling the waist of the All Blacks winger. The ball is pictured slipping out of Wilson’s grasp. The fingers on his right hand are spread out, as if grasping, searching for that elusive prize, the ball.

And the ball is floating away… floating away, along with the marvellous tackle, into the collective memory of the thousands of people watching the Test live and the hundreds of thousands, probably millions, of people watching the Test on television around the world.

For every person involved – players, spectators and viewers – this moment frozen in hundreds of black and white dots in the newspaper photographs will always be the infinity of Gregan’s Tackle.

There was still time, though, for the Wallabies to lose the game. With the clock almost up, the All Blacks, like Napoleon’s Old Guard at Waterloo, mounted a last charge.

The movement began behind their try line. It moved forward in spurts and starts towards the Wallabies’ tryline. Gaps in the defence opened up all over the field but were never large enough to allow a major breakthrough. People all around the ground were standing on their seats and screaming out “Tackle Wallabies, tackle!”

And tackle they did. Desperately and accurately. With the All Blacks only 15 metres out from the Wallabies’ tryline and right in front of the posts, the English referee Ed Morison raised his arm to the heavens and sounded a blast from his whistle for full-time.

The Wallabies had concluded their first unbeaten season of home Tests, and they had won back the Bledisloe Cup.

The night when rugby truly was the game they play in heaven

After eight minutes in the first Bledisloe Cup match of 15 July 2000 – the greatest rugby Test ever played – it looked like the lunar eclipse scheduled for the following night had arrived a day early for the Wallabies.

The Wallabies were spared a total rout by the defensive efforts (once again in a Bledisloe Cup Test) of George Gregan. It was Gregan, the smallest man on the field, who lowered Jonah Lomu while the giant winger was making a thunderous run towards the Australian tryline. If Lomu had scored, as he was threatening to do, the All Blacks would have raced away to a 30-point lead.

The All Blacks had started so brilliantly, with Christian Cullen, Tana Umaga and Lomu making devastating breaks, and the rapidity of the onslaught was something of a bonus by the Wallabies.

This time, there was no Gregan as the last line of defence to stop the winning try.

John Eales, exercising decisive and thoughtful captaincy, told his team that there was plenty of time to get back into the Test. The worst thing they could do, Eales warned, was to try and play catch-up rugby. He told his players they had to get their hands on the ball and then stick with their game plan as if the score were still 0-0.

The advice was correct. The Wallabies, spurred on by a brilliant break by Stephen Larkham, settled into a golden patch of play where they exposed as many holes in the defence of the All Blacks as the All Blacks had exposed in theirs. After 30 minutes, the scoreline, incredibly, was 24-all.

“We’re back, Toddy! We’re back!” Gregan screamed at Todd Blackadder, the All Blacks captain, when the Wallabies drew level.

Later, with only minutes remaining in the Test, the Wallabies took what seemed to be a decisive lead.

Then came a fateful mistake by the Wallabies. Andrew Walker, the replacement winger, kicked the ball downfield. He gained field position for his side but he broke coach Rod Macqueen’s principle that if you have the ball the other side can’t score.

Christian Cullen raced back into Wallabies territory with the ball. Tana Umaga continued the charge even deeper into Wallabies territory. The ball was moved out wide. Taine Randall, out in the backline, took the rush-defence tackle of Andrew Walker and threw a basketball pass to Jonah Lomu.

This time, there was no Gregan as the last line of defence to stop the winning try.

Jonah Lomu breaks through a Stephen Larkham tackle. (Photo by Ross Land/Getty Images)

On Monday, 17 July 2000, the Sydney Morning Herald published a special lift-out commemorating “The Night Heaven Came To Earth.” The main photograph showed a determined Lomu, ball held high on his chest in his left hand, his thigh muscles bulging, bursting through the despairing tackle of Stephen Larkham.

The copy underneath the photograph was ecstatic.

“Once or twice in a lifetime, a sport lives up to its promise, transcending the mere mortal. On Saturday, a world-record crowd – 109,874 people – witnessed a contest that will be talked about as long as any of us live. Put simply, it was the best Test match not just in the history of the Bledisloe Cup, but in the history of rugby union… The two best rugby teams on the planet fought out a contest so epic, so unpredictable, and so preposterous, that some people went home to watch it again on the video… This was the night when the code lived up to its self-appointed title, Heaven’s Game.”

It was also the night, as reported by Jane Fraser, that provoked the matrons of the eastern suburbs of Sydney to start comparing notes on their Bledisloe Cup sex.

The Wallabies need to revive the spirit of 1979 and 1986 to win back the Bledisloe Cup

When the All Blacks won back the Bledisloe Cup in 2003 with a decisive 50-21 victory at Sydney and a less decisive 21-17 win at Eden Park, who was to know that the Cup was to stay with the winners for 14 years, a record number of consecutive series wins by New Zealand?

We have to remember that only a month or so after the Eden Park Test, the Wallabies defeated the All Blacks in the semi-final of the 2003 Rugby World Cup in Sydney.

We should also not forget that the loss at Eden Park broke the Wallabies’ own five-series grip on the Bledisloe Cup. The Australian domination from 1998 to 2002 represents the most consecutive series wins by Australia since the Cup series was started in 1996.

A Bledisloe Cup win, no matter how unlikely, can change the course of history and set in motion a sequence of wins and losses that could not have been predicted before the first breakthrough victory was achieved.

The New Zealand media are not giving the Wallabies much chance of pulling off a series win in 2017. This is rather like the cockiness of the New Zealanders in 1979 and 1986.

Here is Marc Hinton in the New Zealand Herald in a preview of Saturday’s coming Test:

“The Wallabies see weaknesses. If the Lions did it, so can they. They are fitter, faster and stronger than they have ever been. The All Blacks are on the decline. This is their time. Maybe. But highly doubtful… Back-to-back home Tests for the All Blacks without a victory? That’s the closest the All Blacks have come to a crisis since 2009’s three straight defeats to the Springboks.”

A Bledisloe Cup win, no matter how unlikely, can change the course of history and set in motion a sequence of wins and losses that could not possibly have been predicted.

The New Zealand Herald had some depressing statistics to support this New Zealand confidence that their dominance will continue:

“The Wallabies handed over the Bledisloe Cup in 2003 and haven’t touched it since. Over the drought, they’ve won the first Bledisloe Cup clash just three times but then gone on to fail to close out the series…

“The All Blacks may look somewhat vulnerable following a series draw with the British and Irish Lions, however that result looks impressive compared to Australia’s June results which included a defeat to Scotland and two average wins over Italy and Fiji …

“Saturday’s Test will be the sixth straight year that Sydney has hosted the opening Bledisloe Cup Test of the year. The All Blacks have a relatively low 58.33 per cent winning record at Stadium Australia but since losing in 2007 and 2008, the world champions have won six of the last eight.”

The history of recent losses is so dire there is little experience among the players of beating the All Blacks in a Test. Stephen Moore has won five Bledisloe Tests out of the 27 he has played in. The Wallabies’ new captain, Michael Hooper, has won one Bledisloe Cup Test (and drawn two) in the 14 he has played.

But there is some hope in the Wallabies camp with the record of Stephen Larkham as a player with ten wins out of 22 Bledisloe Cup matches.

The Wallabies assistant coach told the Sun-Herald’s Tom Decent that if his players found the right balance between running rugby and the territory game, they could win on Saturday night.

“We don’t want to be predictable to the opposition and we certainly want to be on the same page. It won’t be as simple as kicking everything out of our own half or running everything in our own half. There will be a balance.”

GB Shaw once noted that he welcomed every new book explaining the mystery at the heart of Hamlet as one book closer to someone revealing the truth about the Hamlet character.

This concept can be applied, albeit in a twisted way, to the sequences of Bledisloe Cup Test victories: every winning series brings the victorious side closer to a loss.

The Wallabies are getting closer to a Bledisloe Cup victory. They must be. (Picture: Tim Anger).

The key for the Wallabies to breaking the current 14-series record is to win the opening Bledisloe Cup Test on Saturday night.

The next Test is played at Dunedin, a week later. The NZRU has scheduled South Africa for the Eden Park Test, an (perhaps gratuitous) acknowledgement that they rate the Springboks a more dangerous threat than the Wallabies.

The final Bledisloe Cup Test for 2017 is played at Brisbane, where the Wallabies have had some success over the years against the All Blacks.

Predicting the future is like staring into a dark mirror. We know, though, as the strange history of the Bledisloe Cup reveals, that winning streaks eventually end, and often when the pundits least expect it.

The spirit and achievement of 1979 and 1986 should be the guiding light for the Wallabies to startle the All Blacks and even themselves, and win back Lord Bledisloe’s Cup in a year when few, even amongst the most diehard of supporters, give them any chance of making history.

After all, in the 2017 Super rugby tournament, the Australian sides played 26 times against New Zealand sides. The result? Twenty-six wins to the New Zealand teams.

On Saturday night, the Wallabies have to play with the arrogance Alan Jones instilled into their 1986 counterparts when they knew that “the only thing left to do was to win.”

Michael Cheika has to revive the passion to win that David Brockhoff, the only Australian to win the Bledisloe Cup as a player and a coach, instilled into his 1979 Wallabies with his inspired precepts:

“You’ll run out, you’ll line up on the other side of the halfway mark and you’ll go through them like a madman in a glass factory with a crowbar…

“Hit them like a sledgehammer through a David Jones window…

“Missile them. Don’t give them a sniff…

“Lock the bullies out of the gate at the beginning of the Test. And then for the rest of afternoon we play in the field…

“Breakaways, no excuses, cause havoc at the breakdown like sharks through a school of mullets…

“As for the tight-five, all day like wind through wheat. Not scattered rocks here and there, but like wind through wheat…

“So every lineout a dockyard brawl. Except in our 22 – a row of ministers – no easy penalties.”

Written by Spiro Zavos.

Spiro is a founding writer on The Roar, and long-time editorial writer on the Sydney Morning Herald, where he started a rugby column that ran for nearly 30 years. Spiro has written 12 books: fiction, biography, politics and histories of Australian, New Zealand, British and South African rugby. He is regarded as one of the foremost writers on rugby throughout the world.

Editing and layout by Daniel Jeffrey

Lead image image credit: Nick Wilson/Allsport

Image of Bledisloe Cup credit: Matt King/Getty Images

Image of Nick Farr-Jones and Simon Poidevin credit: Georges Gobet/AFP/Getty Images

Image of Michael Hooper credit: Cameron Spencer/Getty Images

All other images are AAP photos unless otherwise credited.