'I've just won a stage of the Tour de France, mate!': Hindley grabs yellow jersey as Aussie blows Tour apart

Australia's Jai Hindley has said he is "lost for words" after a shock stage victory at the Tour de France earned him the leader's…

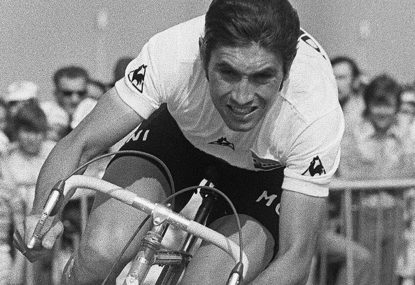

While Lance Armstrong’s seven Tour victories was a feat unparalleled until he had them stripped, the Texan was never really in the discussion as the greatest cyclist of all time, with that particular title belonging to Belgian Eddy Merckx.

Merckx’s 525 career victories included one Vuelta a Espana, five Giro d’Italia and five Tour de France titles, as well as dozens of victories in the one-day classics, and three world championships.

Simply put, Merckx has the greatest palmares in cycling’s history, a list of achievements perhaps best compared to Sir Don Bradman’s – freakish to the point of being regarded as untouchable.

Catch up on the rest of World War Cycling

PART 1: The Prologue

PART 2: The United States of America

PART 3: Italy

PART 4: Doping learnings of America for make benefit glorious nation of Kazakhstan

PART 5: Spain

PART 6: Germany and Denmark

PART 7: France

Cadel Evans re-tweeted this post last week, giving an idea of how far ahead of the competition ‘The Cannibal’ truly is:

1 Merckx = 14 wielerkampioenen http://t.co/2lS8hYhcw3 @MarkCavendish @simongerrans @CadelOfficial @Bartolimichi pic.twitter.com/RLn7av8Yp8

— sporza (@sporza) June 17, 2015

What could possibly stain a career as dominant as this? How about testing positive for doping on three occasions over eight years.

Doping controls were first introduced by the UCI in 1966. While this may seem insane considering the Tour had a history of over 60 years at this point, the UCI were in fact one of the first sporting organisations, along with FIFA, to introduce controls.

Merckx was the defending champion at the 1969 Giro d’Italia and leading the race, when on June 2 the race director came to the Belgian’s hotel room with a camera crew in tow to tell him he had tested positive to a performance enhancer.

He was evicted from the Giro – the first leader to be dumped from a Grand Tour for doping – and given a one-month suspension, which meant he would also miss the 1969 Tour.

It was a disaster, not only for Merckx but for France. The young Belgian was the most exciting and marketable cyclist in the world and had been due to make his Tour debut. Why should their race be punished?

Furthermore, why should Merckx be punished? He had wept when told he was being evicted from the race, and been absolute about his innocence. Surely such a nice young man wouldn’t dope and then lie about it?

With WADA still 45 years away from coming into existence, it was up to the UCI to broker an agreement. They reached the conclusion Merckx had tested positive, and was right to be booted from the Giro, but he probably hadn’t meant to dope, so his one-month suspension was overturned and he was free to ride the Tour.

For the record, he not only won the ’69 Tour, he walked home with the green sprinters’ jersey, the polka dot King of the Mountains jersey, and at age 24 he would also have won the white jersey for best young rider had it existed at the time.

Merckx’s next brush with doping controls came at the 1973 Giro di Lombardia, where he had his first place stripped after testing positive to norephedrine. This time his team doctor put his hand up, saying he had prescribed Merckx with a cough medicine which contained the substance. Merckx was given a fine and a month-long ban.

The final incident came at Fleche Wallonne in 1977, as Merckx and two other Belgian riders tested positive for pemoline – the test for which had only been developed that year. His eighth place was stripped, and again he received a fine and a one-month ban.

While each incident came with a series of explanations and excuses from Merckx – he maintains someone spiked his water bottle at the ’69 Giro – three failed tests paints a pattern. Perhaps not of systematic doping, but certainly of being familiar with what Merckx described to the New York Post in 2011 as “products that made you a little less tired”.

In that same interview, Merckx blamed the epidemic of doping on, “the doctors; they make money”.

Yet one doctor who obviously made plenty of money from cycling is Michele Ferrari, whom Merckx played an integral role in thrusting to the forefront of the sport.

While Ferrari announced himself to the cycling world with his famous comparison of EPO to orange juice, it was his relationship with Lance Armstrong that made him the most sought-after sports scientist in the peloton.

So how did Ferrari meet Lance? In an interview the Italian gave to Cyclingnews in 2003 he said, “I met Lance at the end of 1995; Eddy Merckx introduced us”.

At the time, Ferrari was working with Merckx’s son Axel, who was an accomplished cyclist in his own right, winning bronze in the road race at the 2004 Olympics, as well as coming 10th at the 1998 Tour de France.

However Axel’s place at the ’98 Tour has since come under scrutiny, as he was one of the cyclists listed as having values deemed “suspicious” in a French Senate report into EPO use at that year’s edition.

While one shouldn’t expect a father to know exactly what his adult son is doing at all times, the Merckx family show that cycling’s war began long before Lance Armstrong, or even the advent of EPO.

Futhermore, according to Daniel Friebe, author of Eddy Merckx: The Cannibal, the root of the doping problem remains the same now as it was in Merckx’s day:

In fairness, it was hard to take doping seriously when the authorities clearly did not, at least if the sanctions were any gauge. A meagre time penalty of 10 or 15 minutes, a one-month ban or sometimes just disqualification were the judicial equivalent of a slap on the wrist.

… the tests were too little, too late to uproot a culture of indifference and complicity which far pre-dated Merckx and would persist when his career ended.

Regardless of failed tests, Merckx is still a hero in his home nation. There is a metro station named after him in Brussels, and in 1996 King Albert II of Belgium gave Eddy the title of Baron. As such his family are officially a part of the Belgian nobility, with his son now known as Jonkheer Axel Merckx – an honorific essentially meaning ‘the honourable’.

Next week, the final chapter of the war: Australia, our part in the Festina affair and Lance Armstrong’s rise and fall, and how an eighth place can become first.