'Someone will die': Olympic legend sounds harsh warning if Enhanced Games go ahead

Olympic swimming legend and Australian Sports Commission boss Kieren Perkins has warned that "someone will die" if a multi-sport event that allows athletes to…

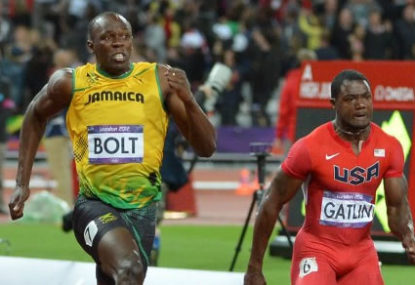

According to some BBC commentators, the recent sprint clash between Usain Bolt and Justin Gatlin at the 2015 World Athletics Championships was a case of ‘good versus evil’ as they openly expressed their preference for Bolt to win.

For example, Tom Fordyce warned that: “should Justin Gatlin be crowned world champion after two doping bans, in the highest profile of all its finals, it would encapsulate for many what has gone wrong and is still going wrong with the sport.”

Not surprisingly, after Bolt won the 100m BBC commentator Steve Cram stated that, “he may have even saved his sport”. Footage posted on Twitter showed Brendan Foster and other BBC commentators celebrating as Bolt crossed the line, and Gatlin berated the BBC for styling the showdown as a battle of good and evil.

Such biased BBC commentary is indeed over the top and makes a simplistic assumption that one is bad or good merely on the basis of having been caught taking illegal performance enhancing drugs (PEDs).

In an era where exposed dopers have never failed drug tests (including Marion Jones and Lance Armstrong), it is simplistic to make such assumptions.

What should be important with regard to the Bolt and Gatlin clashes, at least in terms of media scrutiny with regard to efforts to encourage cleaner sport, is their level of performance and what it may tell readers about the testing regimes of both Jamaica and the USA.

After all, the Jamaica Anti-Doping Commission (JADCO) and the US Anti-Doping Agency (USADA) provide prime examples of the drug testing regimes in both developed and poor nations at a time when national testing remains the most important means of producing drug free sport.

In 2014, of the 25,830 total tests conducted for the sport of athletics, only 3841 were conducted by the International Association of Athletics Federations with just 28 by the World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA). Of the total 9714 out-of-competitions tests, only 1808 were conducted by the IAAF and 16 by WADA.

With Bolt and Gatlin being the best male sprinters of Jamaica and the USA, the very nations that have dominated the 100m and 200m global championships in recent times, it is worth examining the performance of both for possible answers about the effectiveness of national drug testing programs.

For example, Gatlin, who has won three global 100m medals since his comeback from 2010 following his four-year ban for testosterone use, has clearly outperformed other men who made the 2015 100m final who have served doping bans (Tyson Gay, Mike Rodgers and Asafa Powell).

Whereas Gatlin has improved his personal bests in recent years, fellow American Gay ran 10.00 in the 2015 final (9.96 in his semi-final) after running 9.71 at the 2009 World Championships when finishing second to Bolt.

Similarly, what of Bolt? While he continues to win global gold medals, is there a story behind the much slower times he has run since his personal bests of 9.58 and 19.19 at the 2009 World Championships given his 2015 times of 9.79 ad 19.60? Or do we simply accept his lesser form because of less preparation from injuries?

By taking such factors into account, interesting questions and answers may arise which would complicate any simplistic notion of good versus evil, while possibly explaining the current state of affairs with regard to the effectiveness of drug testing.

First of all, one cannot simply guarantee that any champion is clean, not Bolt, not anyone. As one French study found, the microdosing of synthetic versions of natural hormones overnight is both highly effective and hardly traceable, thus leading to the conclusion that more testing was needed between 11pm and 6am, despite WADA “only mandating testing during those hours if specially justified”.

It has also been suggested that the use of carbon isotope ratio testing to distinguish between natural and synthetic testosterone, which has resulted in athletes being caught even when passing the T/E ratio of four to one (including Gatlin), may not be detected in urine because of low concentrations.

Given an estimate that the use of illegal PEDs can aid sprint times for men by around three per cent, it would be brave (perhaps naïve) to declare that someone could win without using illegal PEDs against competitors also using illegal PEDs where races can be decided by the barest of margins.

Second, Gatlin is one of the most tested athletes in the world, having been tested nine times by USADA alone in the first half of 2015 after 15 tests in 2014 and 14 during 2013.

So if Gatlin is cheating the system, then the possibility exists for all athletes to do the same, notwithstanding the advantage that athletes may have in nations with a much less stringent national testing regime.

While JADCO has vastly improved its testing regime, after it was revealed during 2013 that there had been a virtual absence of out-of-competition testing by JADCO for six months before the London Games, blood tests only began in Jamaica during 2015 under the guidance of the Canadian Centre for Ethics in Sport.

However, JADCO has vastly improved the extent of its testing, conducting 119 out-of-competition tests on its track and field athletes in 2014 after just 23 in 2013 and 35 in 2012.

Third, notwithstanding the continued dominance by Usain Bolt and Shelly-Ann Fraser-Pryce, who have both won five global 100m championships since 2008, other Jamaican male sprinters ran much slower when comparing results at the 2013 and 2015 World Championships.

Allowing for best times in different rounds, Nickel Ashmeade ran 20.19 for the 200m semi-final, yet 20.00 in the 2013 semi-final, while Warren Weir ran 20.24 (heat race) after running 19.79 in the 2013 final. In the 100m, Ashmeade ran 10.06 (semi-final) in 2015, yet 9.90 in the 2013 semi-final.

To conclude, wise journalists can do much more than provide a cheer squad for one athlete over another for the sake of creating heroes and villains to support a good versus evil context. Perhaps they can actually do some research, in line with the demands of national and international drug testing regimes, to try and link the pieces together in order to possibly provide a more sophisticated story.

It may be that microdosing synthetic hormones remains a real problem, which allows athletes from both rich and poor nations to cheat, at least for those in the know.

Or it may be, given tougher testing in recent years has led to some decline for Jamaica at the 2015 World Championships when compared to previous years, that perhaps the sport can be cleaner if other poor nations also adopt a tougher testing regime.

As CBS Chicago’s Dan Bernstein argued in 2012, independent minds “have a responsibility as healthy skeptics” with regard to “the dirty landscape of the Olympics and sprinting in particular”, and need to express “a clear mind” rather than “wasting words extolling the greatness of Usain Bolt”.

To describe Justin Gatlin as a villain in such a sport where many global sprint medalists have been banned for illegal PED use, and to imply that Usain Bolt is clean just because he has passed every test, borders on naïve journalism that is clearly guilty of downplaying all possibilities surrounding the realities of the drug use in sport debate.

Having said the above, I applaud both Bolt and Gatlin for being champion sprinters and putting on a great show in 2015, but let us not allow sentiment to get in the way of telling a thorough story by raising all possibilities about the battle to address drugs in sport.