Luke Beveridge is on borrowed time - he's an inconsistent coach who gets inconsistent results

Bevo loves playing VFL players in the AFL and in many ways, he is this era's Kevin Sheedy, except a poor man’s version of him.

It was not only the football contest between bitter rivals a hundred years ago that made this grand final legendary

In recent times the AFL has been no stranger to scandal with the Essendon saga dominating the headlines of all major news outlets around the country.

But there have been numerous controversial episodes during the turbulent history of the VFL/AFL. The first major scandal in the sport erupted more than a century ago.

In September 1910, with Carlton poised to win its fourth premiership in five years, the Blues’ popular captain-coach, Fred ‘Pompey’ Elliott, was given unsettling information. Long afterwards he told one of his grand-daughters the little-known story of what happened.

The information came from Carlton officials, who had been quietly investigating some perturbing rumours. They told Elliott to go to a certain restaurant at a certain time. If he hid behind a particular Chinese screen, they said, he would hear things. Elliott went, and he did hear things – very disturbing things.

The upshot the following Saturday was sensational. Three players were mysteriously withdrawn from the Carlton side just before a crucial final. The reason that explosively emerged was that they had been bribed to play dead.

These allegations transformed the mood at Carlton. Confident cohesion gave way to acrimony and upheaval. Elliott found it impossible to keep his players united and focused.

The Blues still managed to reach the grand final, but for some of them it was an opportunity to release bottled-up frustrations and show they were genuine.

In the premiership decider they were up against another VFL powerhouse, Collingwood. As representatives of a proud and successful club, Collingwood’s players were no shrinking violets, and ready to respond with interest to whatever the Blues threw at them.

A series of unsavoury incidents marred the match. The longer it went the more blatant they became. During the final quarter, with the Woods ahead and the game slipping away from Carlton, a wild brawl erupted.

With players exchanging haymakers, teammates from both sides rushed to get involved. Several belligerents were felled. Officials joined the fray, and enraged supporters jumped the fence to participate. Police entered the arena as well.

The umpire, Jack Elder, who officiated at 295 VFL matches, later declared that this was the worst fight he ever saw on a football field. Newspapers described the savagery as unprecedented. The two clubs had been relatively friendly (the presumption that they have always been enemies is a common misconception), but not anymore. The 1910 grand final ushered in more than a century of fierce animosity.

Clashes between them during the ensuing seasons were always spirited and customarily close. When George Challis, a brilliant recruit from Tasmania, joined Carlton in 1912, his fourth match was against Collingwood, and the Blues lost by a point.

In 1913 there was another thrilling clash, and Challis was on the losing side again when Carlton ended up a goal short. In 1914 the growing rivalry produced a draw, and there was a ferocious contest in the return match: two of Challis’ teammates played on despite severe early injuries – one had three broken bones in a kicked hand – and Carlton prevailed by just seven points.

The trend continued in 1915. Collingwood secured top spot by losing only two matches before the finals, but it was Carlton who inflicted both defeats – the first by two points on Queen’s Birthday, and the second by an even smaller margin.

The Queen’s Birthday clash, especially, was a classic. Jack Worrall, the Essendon coach who doubled as an authoritative football journalist, eulogised the “exceptionally high quality” on display: “it was as even and as brilliant a contest as could possibly be seen.”

This match was long remembered for a mesmerising performance from the Pies’ famous spearhead, Dick Lee, who kicked nine of his team’s 10 goals and hit the post twice. George Challis was also acclaimed for a sublime display against his usual Collingwood opponent, talented wingman Jim Jackson.

The return encounter in August, when Carlton snatched a one-point victory with a late goal, was another epic. The Football Record described it as a thrilling spectacle that gave the large crowd “two hours of glorious forgetfulness of war and its horrors.”

Gallipoli was casting a growing shadow. As supporters made their way to the game, the battle of Lone Pine was raging, and Australian lighthorsemen had just charged at the Nek with disastrous results.

Carlton and Collingwood were clearly the two best teams in 1915. The grand final that eventuated between them was anticipated with relish. It was to be their first clash in any final – let alone a grand final – since the violent premiership decider that had launched the bitter rivalry five years earlier.

Players from both clubs had enlisted for that other faraway conflict. Challis had volunteered in 1914, but had been rejected as medically unfit because one of his toes curled up over its neighbour. The defective digit stayed there permanently, as it had all his life.

This had neither perturbed him nor prevented him from becoming one of the fastest and most brilliant footballers in the nation. The idea that such a swift and skilful footballer could be deemed unfit generated widespread amazement and amusement – a “regiment of Challises would be a great asset for the Australian army,” the Record remarked.

The appalling casualty toll at Gallipoli prompted the medical authorities to review their attitude. Challis volunteered again, and this time he was accepted. His usual Collingwood opponent, Jim Jackson, also enlisted – remarkably, on the same day as Challis, 16 July 1915.

Another to enlist that month was 22-year-old Alf Baud, Carlton’s acting captain. Baud was talented, versatile, tactically sharp and an emerging champion.

Two of Jackson’s Collingwood teammates had enlisted together two days before him. Paddy Rowan and Mal “Doc” Seddon were the closest of mates on and off the field. Rowan, an intriguing character, was playing for the Magpies under a false name – as Seddon and others knew, he was really Percy Rowe.

He volunteered for the army under his real name, and he and Seddon were posted to the military training camp at Seymour.

This was not Rowe’s only significant enlistment. He was getting married to Louisa (Louie) Newby. Louie had been close to Seddon ever since their childhood together in the same Collingwood street. Everyone assumed that Doc and Louie would end up together, but Doc was shy and not one to rush things.

Percy, Doc’s dashing teammate from the country, was altogether different. After Percy met Louie – it was in fact Doc who introduced them – the attraction was mutual, and Louie became pregnant. Their marriage was hastily arranged. Doc was best man for his best mate. Rowe and Seddon had to obtain leave from their camp for the ceremony – and for Collingwood’s semi-final afterwards.

This was not necessarily straightforward. A fortnight earlier there had been consternation in the Woods’ rooms before the game when Rowe and Seddon failed to arrive. Leave at Seymour had been cancelled due to a meningitis outbreak.

With this in mind, Jack Worrall remarked in his column that if any difficulty happened to arise on grand final day about getting military leave for such pivotal players as Rowe, Seddon and Jim Jackson, Collingwood could not win the premiership.

This declaration might have given someone food for thought.

Jackson was in fact out injured anyway, but Rowe and Seddon were fit and eager to excel in the grand final.

However, they became involved in another pre-match controversy when they were again denied leave. Moreover, they found themselves ordered to participate in a 12-mile march on the morning of the match.

The Collingwood secretary drove hastily to the camp. He managed to sort out the imbroglio over leave, and rushed the key duo back to Melbourne. They reached the MCG in time, but the strenuous march had left Rowe and Seddon jaded and aggrieved.

Collingwood partisans suspected skulduggery. Carlton had plenty of adherents, and they could crop up in all kinds of inconvenient places. The umbrage has endured. Eddie McGuire and other present-day Pies fans familiar with the episode remain resentful.

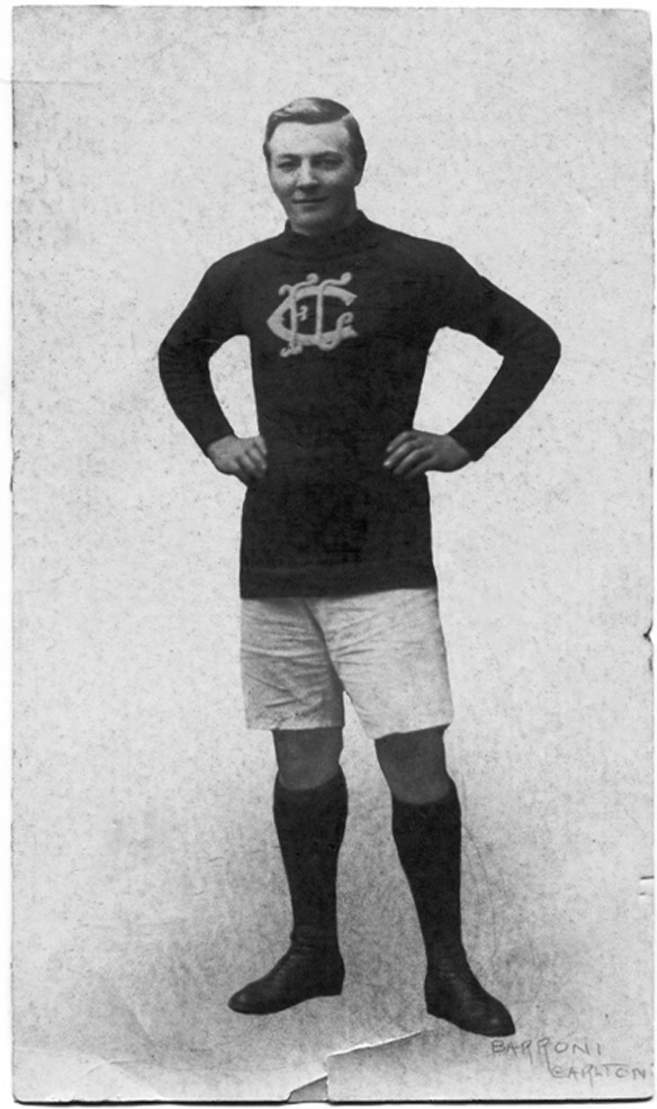

George Challis in his Carlton Football Club uniform. (Image: supplied)

George Challis in his Carlton Football Club uniform. (Image: supplied)

Baud won the toss, and gave Carlton the initial benefit of a useful breeze. The Blues started well, but kicked inaccurately. At quarter-time they had quadrupled their opponents’ scoring shots but were less than two goals ahead.

A highlight for Collingwood had been a splendid chain of possession – including a pass from Seddon to Rowe – that culminated in a goal scored by Dick Lee.

The Pies redoubled their efforts in the second term, but could not reduce the margin. They kept in touch, though when Seddon goaled just before half-time, the margin was 16 points. But when spectators paused to review and predict during the long interval, few could discern grounds for Collingwood optimism.

However, a transformation ensued, as dramatic as it was unexpected. The Blues found themselves defending desperately to withstand a Collingwood surge. The Magpies kept pressing fervently; their opponents kept resisting tenaciously. It was an intense contest of the highest quality, and the large crowd was captivated.

Worrall described it as “an exceptionally brilliant and thrilling encounter”; enthralled onlookers were following the “glorious spectacular struggle” with “wild excitement.” Melbourne Punch described it as a “brilliant display of football” that was “often faster than it seemed possible to play.”

The Pies had taken control, but did not get full scoreboard value from their pressure and possession. When Carlton’s full-back made an error – in that era he was also surnamed Jamieson (Ernie, not Michael) – Dick Lee dispossessed him and snapped accurately. The Collingwood fans roared with such thunderous fervour that it “simply beggared belief,” Jack Worrall wrote.

When they realised that the boundary umpire had ruled that the ball was out of bounds before Lee gathered it, their chagrin was no less intense.

Undaunted, the Pies kept coming, urged on by their centreman and captain-coach Jim McHale (who was becoming increasingly known as ‘Jock’). When Lee goaled midway through the last quarter, another tremendous roar confirmed that the Pies now had the lead as well as the momentum.

Carlton responded with an attacking thrust towards Herb Burleigh, the Blues’ leading goalkicker that year. He flew for the ball and failed to hold it, but the umpire paid a mark – “a shocking decision,” Worrall asserted. It was the crucial moment. Burleigh goaled, and the Pies’ morale plummeted.

Rowe and Seddon were exhausted. They were “not quite themselves,” The Age thought. The Leader felt they “appear to have slowed up since they enlisted.”

Carlton goaled again, and resistance crumbled. The Blues, relieved and elated, piled on more goals in quick succession, including another two from Burleigh. The margin at the end, 33 points, in no way reflected the pervasive tension not long before.

An award for best player in the grand final was decades away, but if a Norm Smith Medal had been up for grabs in 1915 George Challis would have been a contender. His proficiency and creativity were acclaimed, and his outstanding disposal was, as usual, conspicuous.

Within a month Challis sailed away to war as a sergeant in the infantry. In Egypt his battalion was for a time based at the AIF training camp at Tel-el-Kebir, which became a venue for VFL reunions.

Challis caught up with Alf Baud there, as well as the Collingwood trio he had played against in big matches – Jackson, Rowe and Seddon. Rowe was a combatant in the best-known boxing bout at Tel-el-Kebir; he was in hospital with ‘concussion’ afterwards for weeks.

The fickle “fortunes of war” were hardly fortunate for a number of those who had played in the 1915 grand final. Challis was killed by a big shell at Fromelles in July 1916. Admirers of the battalion favourite could not find much of him to bury.

In December 1916 Percy Rowe was fatally wounded near Gueudecourt. He never saw his child – Louie had given birth to a son earlier that year. She named him Percy.

A shell fragment fractured Alf Baud’s skull in 1917. He was reported to have died; his condition was precarious, but he eventually survived. His vision was severely and permanently damaged, though, and the momentous grand final when he led the Blues to victory at the age of 22 proved to be his last VFL match.

“Baud would have been a football sensation had it not been for the war,” Roy Cazaly concluded.

Herb Burleigh, the Carlton goalkicker, was severely wounded at Polygon Wood. He made a comeback after the war, but his arm was not right, and he retired after just three more games.

In contrast, “Doc” Seddon not only survived the war but also resumed in the VFL successfully. In 1919 he secured the premiership he had missed out on four years earlier, and represented Victoria as well.

He married Louie, his childhood friend and Percy Rowe’s widow. Louie’s son, sired but never seen by Percy, ended up playing for Collingwood like his father and stepfather.

Carlton’s win in the 1915 grand final was the club’s fifth premiership in a decade. During the following two decades, however, Carlton won none.

The Blues did not meet Collingwood in a grand final again until 1938. Seddon, now the Woods’ chairman of selectors, reminisced before the match about 1915, and observed that the arduous route march – still notorious at Collingwood decades later – had been ordered by “an adjutant,” who was presumably a Carlton supporter.

The officer concerned has never been identified. Rowe and Seddon were then in the 29th Battalion. Its adjutant in September 1915 was John McArthur, a 41-year-old professional soldier who was to accumulate an outstanding record at the Western Front.

Born in Scotland, McArthur had grown up near Toowoomba, and had served in a Queensland contingent in the South African War; having joined the permanent army after his return, he was located in Queensland for the following decade.

This hardly seems the background of a fervent Carlton devotee who would be keen to thwart Collingwood.

However, he had been transferred to Melbourne in 1911. Might he have developed an allegiance to the Blues during the ensuing four years?

Whether McArthur ordered the march – and whether he had a Carlton affiliation – remains unclear. It’s an intriguing aspect of the 1915 grand final, one of the most memorable in VFL/AFL history.

Ross McMullin is an award-winning historian and biographer.

His biography of George Challis — and the story of the 1915 Grand Final — is in his latest book Farewell, Dear People: Biographies of Australia’s Lost Generation, which has been awarded the Prime Minister’s Prize for Australian History and the National Cultural Award.

His previous books include Pompey Elliott, which won awards for biography and literature, and Will Dyson: Australia’s Radical Genius, which was shortlisted for the National Biography Award.

Ross has also written the ALP centenary history The Light on the Hill, and another political history So Monstrous a Travesty: Chris Watson and the World’s First National Labour Government.

He recently delivered the 2015 Tom Brock Lecture entitled “Retrieving Ted Larkin (1880-1915): Outstanding Footballer, Acclaimed Organiser, Original Anzac”.