It’s a quiet time of the year for tennis. The dust has settled from the Australian Open fanfare and most news has revolved around Andy Murray’s family affairs rather than the various ATP 250 level events going on around the globe.

Those four pillars that have been at the apex of the game for much of a decade now: Roger Federer, Rafael Nadal, Novak Djokovic and Andy Murray. These men are the headline acts in a show that requires 128.

It’s been a familiar story with few surprises; these four greedy victors have burrowed through draws like a mole in a foam pit to leave little silverware or spotlight for other hapless grinders. Some would argue of late that Stan Wawrinka is an honourary member, but the focus of this article lies on another player overlooked even more.

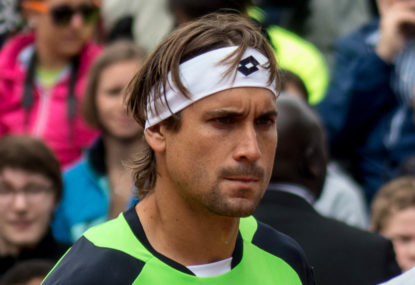

David Ferrer is used to getting the short end of the stick. Indeed, so much of his career has been at the right-hand of others that he wouldn’t mind getting this article on the slow weeks of the tour either.

Born in Alicante, Spain, Ferrer was a dime-a-dozen in an era of tennis saturated with Spanish talent. At five feet nine inches, he was the runt of the litter that came through in the mid-noughties among Feliciano Lopez, Fernando Verdasco, Nadal, Nicholas Almagro, Juan Carlos Ferrero and Tommy Robredo.

Even their names sound stronger, more authentic in their quest to ignite and steer their Spanish temper to victory. Yet Ferrer has steadily outshone all of them bar the great Nadal.

It’s not a booming forehand or serve, nor silky hands and talent that have made Ferrer so good, yet not quite good enough. At first viewing the game looks hard work for him. A top-spun clay version of Lleyton Hewitt springs to mind when trying to evoke a comparison, the very man he beat to end his career at this year’s Australian Open.

It’s a real blue-collar set up when you watch him play. There’s little nonsense in his technique, ‘modern day vanilla’ almost describes it, a tennis racquet on legs isn’t far off either. Yet there is admirable strain and fight seen in every corner of his face during his shots, you know he’s making bloody hard work of it.

As a teenager under the paternal eye of his longtime coach, Javier Piles, Ferrer was molded into the typical grinding European clay style. A lack of effort in training once led Javier to lock Ferrer in a tiny ball closet for hours with only a piece of bread and some water.

This incident was the last straw for Ferrer, and he quit tennis to work on a construction site in a career that lasted all of a week.

The experience of a blue-collar job didn’t quite have the same appeal to Ferrer as training hard, and he returned to Piles humbly asking if he could play tennis again. And the rest, they say, is history. Javier coached Ferrer from those tender teenage years right up until 2013, an unusually long stint given the short tenure of your average professional coach.

Ferrer first cracked the top five of the ATP rankings late in 2007 after a semi-final run at Flushing Meadows and a final appearance at the Tennis Masters Cup. The view of the summit was brief, however, as he slipped back into teen-ranked obscurity again until late in 2010.

The rise of Ferrer’s peak years would coincide with one of the most talent-saturated eras in tennis. Federer, Nadal, Djokovic and Murray were all at, or near, the peak of their powers, and their appetite for victory left little remains even for players of Ferrer’s ilk.

You see, despite his diminutive stature, vanilla strokes and lack of flair, Ferrer is one hell of a modern day player. He is the definition of a hardened tour professional, his thick veiny legs ornaments of a life spent chasing millions of tennis balls. It’s a job. Side to side to side, point after point, breath after breath after lung-busting breath.

This grinding method of his is particularly effective, the few players who seem to beat him with regularity are the freaks, the otherworldly players that we watch with our chins flush to the ground in disbelief.

He’s really fast, not as fast as Djokovic, but he’s right on his shoulder. He has a great forehand, not like Federer’s liquid whip, but the tour talks about it. He is an amazing competitor, perhaps only the tireless Nadal can out-work the tour workman. He’s pretty darn complete, perhaps not quite as polished as Murray, but gosh it’s damn close.

And so it is, that for all his incredible attributes, he has always been just shy of that level we salivate over. The bar for greatness hovers tantalisingly above him, daring him to fall over the line in a tournament pitted against the greats.

Since 2011 much of his time in the rankings has seen him as the doorman to the super elite. To rub shoulders with Federer et al, you better be good enough to dust this Spanish bouncer off with regularity.

I’m sure he lies down at night and wonders what the heck does a mortal have to do to just once be the last man standing in a Grand Slam. He knows he’s David against four Goliaths, I’m sure he was at peace with that fact long ago, but surely with four slams a year, across a whole career, the narrative must play in his favour?

Just once?

Life is not that fair, and Ferrer is probably at peace with that too. He’s made a heck of a chip stack with the cards life dealt him, and he’s a shining example to all aspiring professionals of maximising one’s gifts.

Whenever he decides to hang up the boots, the tour won’t remember him for having the greatest forehand, the greatest serve or the greatest talent.

Perhaps instead, he will be remembered as the greatest that never won a slam, a testament to him and the era he played in.