'I've just won a stage of the Tour de France, mate!': Hindley grabs yellow jersey as Aussie blows Tour apart

Australia's Jai Hindley has said he is "lost for words" after a shock stage victory at the Tour de France earned him the leader's…

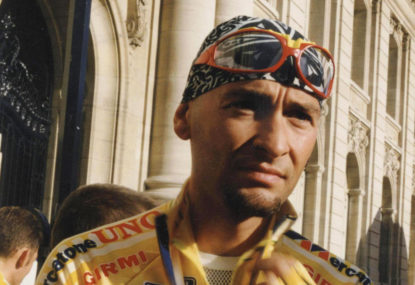

For the last five years of his tragically short life, Marco Pantani maintained that his blood samples had been manipulated during the 1999 Giro d’Italia, leading to him being expelled from a race he was leading by over five minutes with just two stages to go.

Now, more than 12 years after the cycling legend was found dead in a hotel room, aged 34, having overdosed on cocaine, Italian police say they believe Pantani was right – his blood was tampered with.

More specifically, the Naples Mafia are thought to have threatened and bribed the medical staff hired by the UCI, so as to ensure ‘Il Pirata’ didn’t win the race and cost them millions in betting payouts.

Augusto La Torre, one of the heads of a Naples crime syndicate, was quoted in Gazzetta dello Sport as saying the following in a police report:

“I spoke to several other bosses and they told me there was a risk of going bankrupt and losing several million if Pantani won the Giro, just as happened with Maradona and the Napoli football team in the eighties.

“I can say that the clan contacted the people who did the control and corrupted them. I absolutely exclude that they were threatened, it was just corruption.”

» Check out World War Cycling, Joe’s in-depth series on doping in the peloton

The medical staff who tested Pantani’s blood after the Madonna di Campiglio stage are believed to have used a technique called deplasmation to alter Pantani’s results.

Pantani was booted from the race after his blood returned a haematocrit (percentage of red blood-cells) level of 52.

At the time, with no test available for the banned performance-enhancer synthetic EPO, riders whose haematocrit exceeded 50 were expelled from races.

Officially, this ban was for the rider’s health, as such a high level of red blood-cells can be dangerous, but the implication was that the cyclist in question was using EPO to artificially boost their blood. Thus, without making a defamatory claim about an athlete, you could cast massive aspersions over their legitimacy.

Pantani – who had won the 1998 Giro and Tour de France, the last person in history to do the double in the same year – took it as the ultimate insult, and sunk into a deep depression.

While he made cameo appearances at races in the coming years, one can pinpoint the end of both his career and entire life as beginning with that failed test.

Of course, a 2013 French Senate inquiry into the ’98 Tour used retroactive testing to find Pantani had won the world’s most famous bike race while using EPO, so it’s likely that Pantani was using the drug during the ’99 Giro (I’d go so far as to say he definitely was, because that was the only way to win a Grand Tour at the time).

But Pantani worked with some of the world’s best doctors and sports scientists. Whoever was instructing him on EPO use would have taught him that an injection of the stuff with just two real stages of racing left (the final day tends to be a ceremonial ride with no real changes in the overall classification) is a ridiculous idea.

With a five-minute lead over his nearest rival, all the finest climber of his generation needed to do was sit on second-placed Paolo Savoldelli’s wheel for three days, and the race was his.

It must have been the most frustrating part for Pantani – he likely had hard evidence that he hadn’t cheated on that stage, but that would have been by showing evidence he had instead cheated on another day.

And that’s likely how the Mafia managed to do what they did. It’s not impossible to manipulate the levels of a clean rider, but it’s certainly a lot easier to get away with doing it to a rider who is using.

So it can be difficult to find too much sympathy for Pantani, but while he was rightly expelled from the race, it was for the wrong reason. And where his contemporaries such as Lance Armstrong, Jan Ullrich and Bjarne Riis ultimately got caught too, they had long, successful careers first, and even though they’ve done it tough since being found out, at least they’re still alive.

Perhaps the ultimate tragedy is that though the police have announced their findings, the statute of limitations on the case has expired, meaning it’s unlikely anyone will ever pay a price for the incident which ended up costing Marco Pantani his life.