Early in the Geelong-Gold Coast match, Tom J. Lynch was the recipient of a generous free kick after Tom Lonergan indulged in the once-prized art of punching the ball away from his opponent. He scored a goal.

Minutes later, one of his teammates received a similar free when Harry Taylor did what most students of the game would call “spoil”. In the same quarter, Lynch received another free in front of goal after Lonergan impeded his run in a way imperceptible to anyone not equipped with a Hubble telescope and the ability to slow down time. He goaled again.

This is pretty unremarkable stuff. Many have commented on the hyper-technical application of the “chopping the arms” rule. Many have noted the broad interpretation of the rule that has at times produced unpredictable results. Some have pondered how many goals Lockett and Dunstall may have kicked if the rule had existed in their era.* And the two free kicks received by Lynch had scant influence on the outcome of the game.

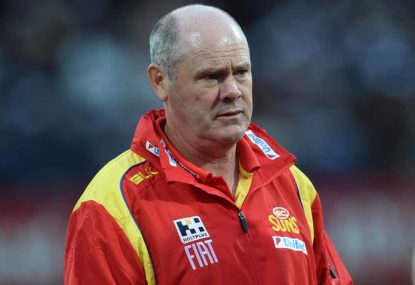

What is notable is that the decisions came after Suns coach Rodney Eade griped that Lynch had received short thrift from the umpires in Gold Coast’s loss to North Melbourne the week previous.

Lynch had one free kick in that match, in which the ball entered the Suns’ forward line 49 times. In the Geelong match, the Gold Coast went into the forward 50 a mere 34 times, with Lynch receiving two borderline frees in front of goal. Statistically it’s not earth-shattering stuff, but Eade’s intervention raises an interesting point.

He’s not the first coach to fire a shot across the umpires’ bow after a match. Indeed, other coaches have approached umpires at quarter and half-time breaks to raise issues and ask questions.

The extent to which this altered and alters the outcome of subsequent umpiring decisions is difficult to quantify – but it’s human nature than when a point has been raised with you, it will play some role in your considerations later – even on an unconscious level.

AFL umpiring operates like a mixture of statute-based law and common law. There are written rules which umpires, like judges, interpret and apply to the facts before them.

For the judges it is somewhat easier though less straightforward: they have a prolonged period to study the facts, to weigh the letter of the law, and the ability to consider previous decisions recorded in writing for comparison. This last factor is particularly important – following precedents in interpreting the law guides judges, and umpires, towards consistency.

Fans – and no doubt players – can learn to live with rules changes they dislike. Inconsistency, however, is intolerably unfair. The rules of the game should be reliable and applied (as) equally (as possible).

In the strictly statue-based legal systems based on the Napoleonic Code, the law is eminently predictable. It is also infuriatingly rigid, leading judges to throw out cases rather than strictly apply a narrowly defined law that will produced a manifestly absurd outcome in a particular situation.

AFL rules are more like the common law, which allows judges far more leeway in interpretation and application. However, the umpires are even more autonomous than judges – they are free to defy precedent, even precedents set by decisions they themselves have made in that very match.

Politicians and other public figures will comment, and complain, about court decisions. Some degree of political pressure can be placed on the court system if there is sustained scrutiny and criticism.

However, judges can easily defy this sort of pressure by holding up the letter of the law and the precedents on which their decisions are based. Umpires can point to the rules, but that’s where it ends. Their interpretations are less easy to justify in a tangible, methodical way, and as such they’re more vulnerable to influence. They are, after all, only human.

Coaches commenting on or questioning umpiring decisions during or after a match will plant a seed in the minds of umpires – and the umpiring officialdom. This input can be a healthy thing if the umpires are getting things wrong, but when considered with deeper complexity becomes problematic.

Which umpires are influenced? For how long? How much? Will they only consider the point raised when it comes to the team of the coach who spoke out? Are the words of some coaches given more weight than others? Would comments made by a coach to umpires at half time cause a different application of a rule in that very game?

When the League introduces a rule, or changes the definitions within a rule, there’s a degree of training or re-education involved for umpires. When this is done badly, it produces bad (or inconsistent) outcomes. The ability of coaches to raise these issues forms a bulwark against bad policy.

Club officials and coaches can question umpiring, within limits. When Sydney Swans chairman Richard Colless described the umpiring in a match against Brisbane in 2004 as “disgraceful… incompetent… a joke”, the Club was fined $5000. That same season St Kilda and Collingwood received the same penalty for comments made by Grant Thomas and Mick Malthouse. Thomas copped a huge fine the following season for letting rip. Malthouse ran into this sort of trouble on a regular basis.

The comments that draw fines are usually spur of the moment and motivated by frustration, naturally producing a bit of intemperate language. But coaches, and club officials, know how to raise questions – and plant seeds of doubt, if not change – without paying thousands for the privilege.

A complete ban would be totalitarian and profoundly unhelpful to the development of the game, but fans and League officials alike should be vigilant to ensure some critics and their clubs do not throw more weight around than others.

*No one could chop Lockett’s arms anyway, so maybe that’s a hyper-hypothetical.