Stoinis clubs stunning IPL ton, makes tough chase look a cinch with clutch final-over barrage

Marcus Stoinis produced his first IPL century and it was a beauty. He went 6, 4, 4, 4 to finish off the Lucknow Super…

Recently I saw ‘The Underarm’, a two-act play about two brothers, one Australian-born, one New Zealand, opening an old wound: their incompatible views on the underarm trundled on a hot and bothered afternoon at the MCG in February 1981, at Australian captain Greg Chappell’s instruction.

For anybody unfamiliar with that surreal, needlessly demeaning episode in Australian sports, know that it excited tremors of vengeful vibes and excoriating jibes from across the Tasman.

Even today, the odd chirpily unforgiving Kiwi insists it’s the perfect sum-up of Australian sporting principles: in Australia, Chappell was forgiven quickly enough (by most), but perhaps exonerating himself took a lot longer.

‘The Underarm’ (penned, for the record, by Kiwi Chris Brougham) got me thinking not so much about summer 1980-81, but ’81-82, Duck Summer: the summer Greg Chappell’s confidence didn’t so much leave him as sever all ties and deny all prior association.

It wasn’t a question of when he’d get it back, or how, but if. It was that bad. Each duck hatched a demon. Each demon hatched a duck. Watching him face up was briefly a national blood sport.

All sorts of guile laced the bowling that summer – with Imran Khan, Sarfraz Nawaz, Michael Holding and Colin Croft in town, the ducks could’ve happened to anybody. But they didn’t. They happened to Greg Chappell.

His memoir offered a simple explanation – he wasn’t watching the ball out of the bowler’s hand as closely as he once had. But the root of this distraction, the discomposure, the demon if you will, may have been his discomfiture at the previous summer’s ‘incident’: a demon delayed a year, all the more zealous for its wait.

As a kid, it annoyed and puzzled me to overhear some adults enjoying his mortification. Their sense of hardiness and fair play and patriotic pride still smarted, and they felt he had it coming. Maybe he did. But their satisfaction may also have had something to do with Chappell having always seemed a bit formal, a bit princely even, too immaculately groomed; a bit singular.

Whatever, the drama made for drollery and raillery. At the MCG somebody smuggled in a duck and let it loose on the grass right behind GS Chappell as he made his solemn entrance. A harmless prank, to be sure, but we could be a harsh lot, back then, if someone was really going through it (Lindy Chamberlain was tried that year (not that their woes equate) and we know how much mercy Joe Public gave her). The trespassing duck, for the record, looked only very briefly stumped, then thoroughly chuffed, like it had always suspected fame was in its stars.

Chappell hadn’t always known dishonour and discredit: far from it.

Walking home from ‘The Underarm’ in unseasonably balmy night air, I found myself picturing him in the ’70s, around the time of World Series Cricket, when he was golden.

Let me adjust the dials in my Tardis here.

When I was seven, if Chappell failed, my mood fell through a trapdoor. If Bruce Laird failed, so be it. If blonde Rick Darling ran himself out, way it goes. And Ian, Greg’s ruggedly charismatic elder, looked as if he could tolerate a technical glitch.

Greg departed shamefaced and roiling with suppressed upheaval – unsure if his talent had mistreated him or if he’d mistreated it. This bottled-up pain and chagrin did me no good.

An early memory of TV is along those very lines: a sparsely attended Super Test, a first-baller jumping at Greg’s throat, causing him to jerk the bat handle and arc a catch. Suddenly, the screen was a Calypso jamboree. Suddenly he was walking the wrong way across the screen undoing his gloves. The day was ruined.

Channel Nine weren’t so savagely greedy with the ads yet – the camera followed him to the gate, to the eerie echo of one person’s awkward clapping. Feeling a wicked injustice at work, I withdrew to the garden to pat the cat.

His shots expressed something.

Stroking off the back foot through cover the blade was part calligraphy brush. When he cut Joel Garner or hooked Andy Roberts, there was no real violence: a parry here, a willowy swivel there. Walking out to face the West Indies’ wit, agility and ferocity, he had the self-possession and solemnity of Alec Guinness’ Ben Kenobi: he knew the danger, knew he might be struck down.

Equally, oppositions knew if he was in long, his currents would course.

For many Australians now in our forties, he was an early star and symbol. We gravitated to his upright figure – he was familiar somehow, outwardly not much different than say, a friend’s dad, or dad’s friend. And still, he had a touch of mystery.

Balanced, harmonious and handsome, it was near-impossible but endless fun mimicking him in that illimitable realm of the suburban Australian imagination: the garden.

Two individual shots stick in mind.

One I saw on TV, an extra cover drive off wrist-spinner Abdul Qadir, making room Chappell met a respectably effervescing ball in suave two-step, stroking with frictionless flourish that made the blade look an inborn extension of his body.

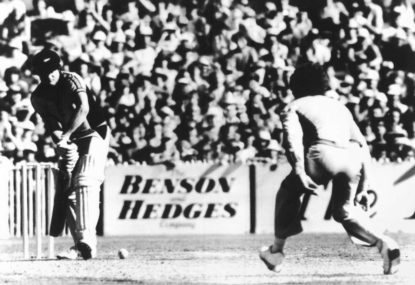

The other I saw at the MCG, deep in Duck Summer. He was like a man who hadn’t spoken for a year, required to deliver a revealing speech in front of 47,000. His five near-phobic runs that day included one stiff but technically correct push – really, and no more – past Joel Garner, for two.

Holding soon sent him packing with a ball so swift my nine-year-old eyes missed it: just a reddish blur and an edge offered in listless, lugubrious obedience.

From the moment he’d come to the middle, his body language said he believed he was done for. Said my dad to his old friend Alan Suitor, as Chappell started the long walk the other way: “Alan, I wouldn’t be surprised if this year’s his last, he’s just not good enough anymore, I’m afraid.”

The next season’s opening Ashes day in Perth, Chappell hit a match-winning century. Torqueing and rolling his wrists he pulled and hooked the quicks. He cut the spinner right out of the keeper’s gloves, and swept velvet-smooth.

He used the crease, used his feet like a dancer. Greg Chappell used The Force.