Since the City Football Group takeover, Melbourne City have been on a steadily upwards trajectory. The progress has sometimes been slow, but it has always been constant. The playing squad has been gradually overhauled, with an influx of genuine top-class talent combined with far greater strength in depth.

There have been off-field changes, too, with the construction of the highly impressive City Football Academy, investment in backroom staff and clear improvements in the many other components of a football club, such as social media and marketing.

The other constant besides change amidst all this upheaval has been the first team coach, John van’t Schip. This is his second stint at the club, having been the original coach in their first incarnation as Melbourne Heart. Returning in December 2013 – just a month before the City takeover – following the sacking of John Aloisi, he was handed a new contract by the contemporary ownership who were keen to maintain stability on the training pitch.

In his time in the A-League, Van’t Schip has been one of the A-League’s most fascinating managers. In his first tenure, he regularly switched between back three and back four systems, often adapting in accordance to how many attackers the opposition fielded.

He was part of the exciting period where modern tactics began to take a foothold in the league, thanks to the likes of Ange Postecoglou at Brisbane Roar and Vítězslav Lavička at Sydney FC. There became a greater emphasis on clear tactical structures and flexibility. Van’t Schip embodies the latter. He frequently changes systems to get the best out of his players.

For example, when he returned to Melbourne Heart after Aloisi’s departure, he immediately instigated a shift from a boxy, rigid 4-2-3-1 formation to a very fluid 4-4-2 diamond, where Mate Dugandzic was asked to play as a right winger without the ball, and as a forward with it, in order to accommodate Harry Kewell in a free role.

That is just the tip of Van’t Schip’s flexible iceberg. In the past two years alone, he has used a 5-2-2-1, 3-5-2, 3-4-1-2, 4-4-2 diamond and his favourite, 4-3-3. This was the formation City started last season with, using Aaron Mooy and Robert Koren ahead of Erik Paartalu.

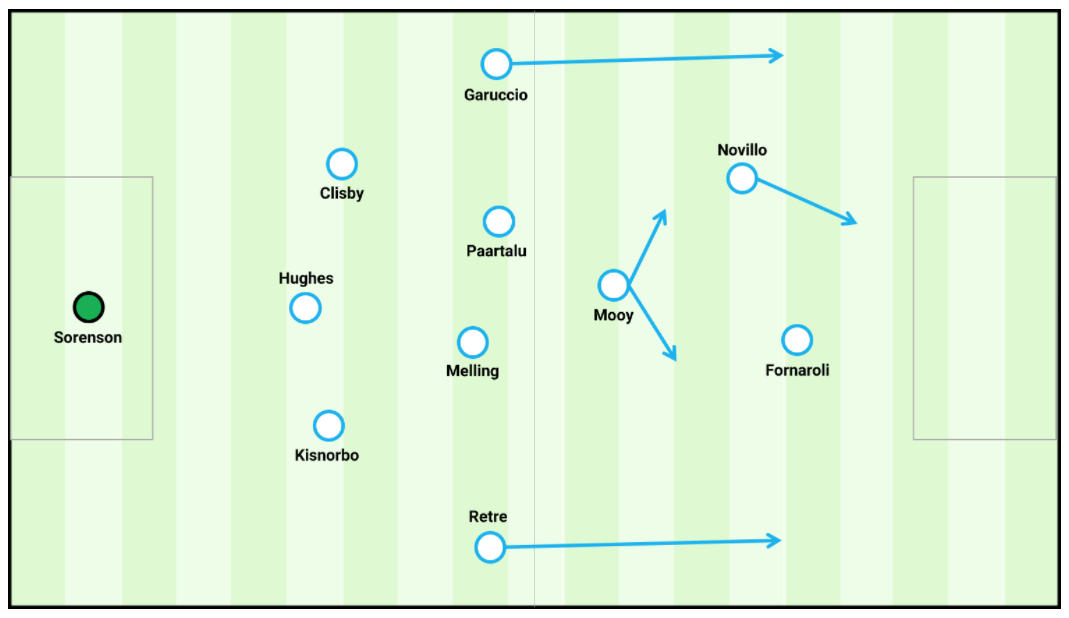

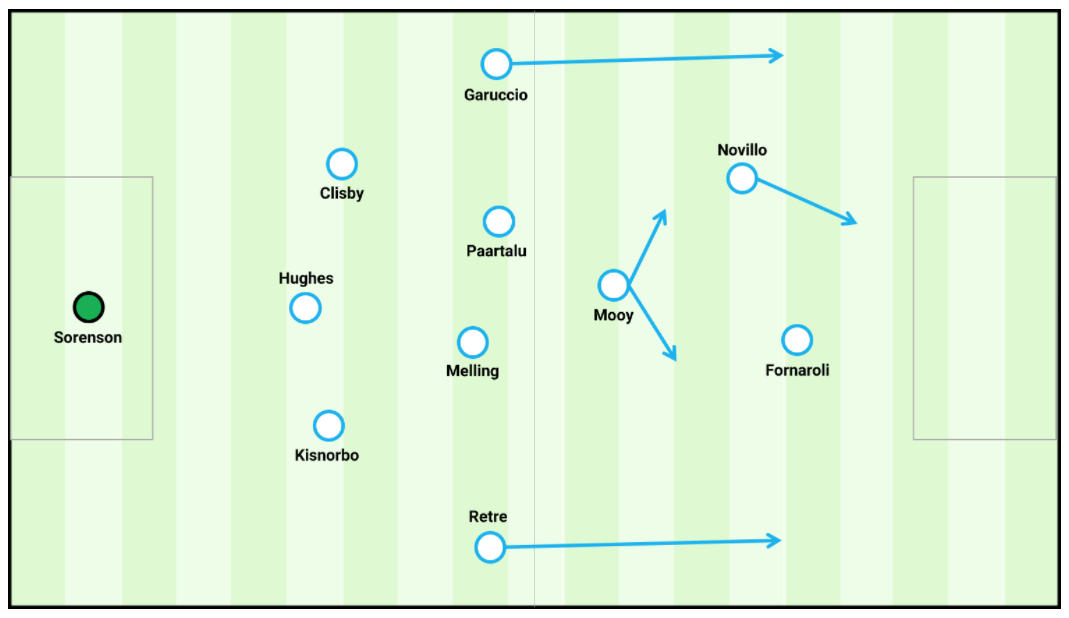

As Bruno Fornaroli and Harry Novillo quickly became the stars of the show, however, Van’t Schip saw fit to adjust in order to maximise their attacking potential. With Aaron Mooy comfortable in a roaming midfield role, City ended the season in a 3-5-2, with Novillo and Fornaroli paired together up front.

This gave both the freedom to work across the width and depth of the attacking third, with the added bonus of a partner to occupy opposition centre-backs, creating more space for the other.

Additionally, by being positioned higher up the pitch when possession was won, they were able to combine quickly on the counter-attack. Together, the dynamic duo dominated in the final third, finishing the season with a combined 35 goals.

However, while Van’t Schip’s tinkering undoubtedly got the best out of his star trio (including Mooy), there were question marks defensively. City never seemed comfortable defending in wide areas in the 3-5-2, as it asked the wing-backs to cover a significant amount of ground.

Additionally, the likes of Patrick Kisnorbo and Aaron Hughes did not seem to have the mobility required as centre-backs in a back three, causing problems when opposition teams matched up man-for-man in attack.

The overall feeling was that City were succeeding because they could overwhelm teams in attack, rather than because of a balanced tactical strategy. With talent like Novillo, Fornaroli and Mooy upfront, that approach could be justified.

Yet recent A-League history suggests the successful teams are those with a solid, stable gameplan. Postecoglou’s Roar were built on a clear philosophy of dominating possession; Graham Arnold’s Central Coast Mariners were the epitome of defensive organisation; Tony Popovic’s Wanderers and Kevin Muscat’s Melbourne Victory were masters of collective pressing.

These teams all had their stars, but the organisation of the side ensured success both when these players were excelling – and when they were not. Importantly, the tactics also ensured defensive balance was maintained. It is telling that the last seven premierships have been won by the team that has conceded the least goals in the regular season.

So, if City have been a steady upwards trajectory, the next step after last season’s semi-final appearance is success in the form of a premiership and/or Championship.

For that to occur, history suggests they need to find that magic formula of defensive solidity, collaborative attacking and star power. They do not lack for the latter, but the former two have been tricky to find despite Van’t Schip’s latest tactical tinkering.

This season’s experiments have been particularly fascinating. With the ball, City play something akin to an asymmetrical 3-1-2-4. With the left-back slightly higher than the right-back, and Michael Jakobsen playing a left-of-centre-back role, space is created for the goalkeeper to move forward in the build up, sometimes playing almost as a right centre-back.

This allows for Neil Kilkenny or Osama Malik to play higher, between the lines, in a #6 role. Ahead of him are two midfielders, typically Luke Brattan and one of Tim Cahill, Anthony Caceres or Paolo Retre. Then, there is a front four stretched across the pitch. The two wingers stay very wide, dragging out opposition full-backs and creating space for the likes of Fornaroli, Cahill and Fernando Brandan in the middle.

The intent is to dominate possession and territory and without a doubt, City have been one of the most imposing sides tactically this season, always pushing opposition teams very deep with their control of the ball and desire to play in the opposition half.

Dotted lines indicate movements without the ball

Without the ball, City shape shift. The #6 drops back into the defence, creating a back four, with the wingers tucking in alongside the two central midfielders. This creates an orthodox 4-4-2 shape. It is complex stuff. It is designed to get the best out of Kilkenny, while also suiting the dribbling ability of Bruce Kamau, Brandan and Nicolas Colazo in wide areas. Importantly, it frees up Fornaroli and Cahill to play together upfront in their preferred positions.

The bigger question amidst all this tactical hijinkery, though, is whether it gets the best out of Melbourne City as a team. Going forward, questions are beginning to rise about whether they can play to the strengths of Fornaroli (who thrives off balls to feet, where he can roll off defenders with his back to goal or simply whip in fantastic curled shots if they stand off him) and Cahill when the two play together.

Cahill, of course, is a prolific header of the ball, and thrives best on early deliveries into the box towards the back post. City are finding it difficult to mesh the two approaches in attack, even with the 3-1-2-4.

Then, without the ball, there are even bigger problems. They have been attempting to play with a high line, but this combined with the complex positional adjustments required when the ball is lost means they are vulnerable to counter-attacks. Additionally, the high defensive line has not always been cohesive, with Kerem Bulut’s wrongly disallowed goal from the draw with the Wanderers a telling example of this.

City conceded late in that game because they tried to kill the tempo with long periods of steady possession – they kept the ball for the sake of it rather than trying to penetrate. It worked initially, but when they turned it over, they then sat very deep, inviting waves of pressure that eventually resulted in Kilkenny’s own goal.

That, in itself, hinted at another issue, that for all of Kilkenny’s strengths, he is not a natural defender. It is hard to imagine Matt Jurman or Alex Wilkinson, central to the league’s best defence at Sydney FC, being positioned as awkwardly for the cross where it was only possible for Kilkenny to clear it in one direction, towards goal.

Overall, while City have been tactically fascinating and entertaining in attack, there is the nagging feeling that they are not the sum of their parts, but rather, the sum of the parts of the stars. While that alone can take you far, A-League history shows that the greatest teams are exactly that – teams.

Melbourne City may succeed in spite of Van’t Schip, but it does not feel like they will succeed because of him.