Stoinis clubs stunning IPL ton, makes tough chase look a cinch with clutch final-over barrage

Marcus Stoinis produced his first IPL century and it was a beauty. He went 6, 4, 4, 4 to finish off the Lucknow Super…

Born in Panama of a mother from Jamaica and a father from Barbados who was involved in the building of the Panama Canal, and early schooled in Cuba, George Headley would never have become a cricketer if he hadn’t picked up Spanish.

When his parents moved to Cuba with 5-year-old George in tow, they fully expected to stay on there as a family. But five years on, when they found their son conversing only in Spanish, the decision was taken to put George in a school in Jamaica, where a tearful mother left him to the care of relatives and returned to Cuba.

That move to Jamaica would be a game changer for at Kingston, cricket found him.

In 1925, at the age of 16 he scored his first century, batting at number three for Raetown against Clovelly. On leaving school, Headley was appointed as a temporary clerk in a magistrate’s court; this enabled him to play competitive cricket for the St Andrew’s Police side in 1926. He missed a chance to play against Lord Tennyson’s 1927 visiting side despite having gained the attention of the Jamaica team for his batting talent, as his job would not allow him leave at the time.

But it was against Lord Tennyson’s 1929 side that George Headley would finally make his first-class debut and again this would be the result of serendipity at work. Headley was to move to the United States to study Dentistry but a delay in the processing of the work permit allowed him to play the match.

In that series Headley was to score 409 runs at an average of almost 82. The rest, as they say, is history, dentistry’s loss being cricket’s gain.

[latest_videos_strip category=”cricket” name=”Cricket”]

George Headley makes his Test debut

In 1930 when the MCC team toured West Indies for what would be the first ever Test series in the Caribbeans, George Headley was among the early choices, and one of the first black players in the team. He would be among only two players in that series to play all four Tests, the other being Trinidadian Clifford Roach.

In the first Test at Barbados, a rattled 21-year-old Headley, upset by the crowd’s barracking (they were convinced he had taken the place of a local Barbadian favourite in the team) would get out for 21, but showing enormous character, he would score a magnificent 176 in the second innings, becoming the first West Indian centurion on debut and the second from the island nations to reach the three-figure mark.

Despite his heroics, West Indies would only manage to draw the Test.

In the second Test at Trinidad, Headley found himself for the first time playing on a matting wicket instead of the grass that he was used to. His scores of eight and 39 added to the misery of seeing his side lose the Test.

By the time the two teams came to British Guyana for the third Test, Headley and Roach were determined to take on both the English attack as well as the responsibility of reversing the result of the previous Test on their young shoulders.

February 26th 1930 – West Indies v England, Georgetown

From the first ball Clifford Roach decided to take on the attack led by Bill Voce and Wilfred Rhodes, two of England’s most famous pre Second World War bowlers. When Headley walked in, the scoreboard read 144 for 1.

The two young men put on a master class of batting, and when Roach departed for 209, the first double century by a West Indian, Headley was going strong with his exquisite offside strokes. He would finally be run out for 114 and West Indies would register a first innings total of 471.

The English batsmen would wilt against the pace of Learie Constantine and George Francis and be dismissed for a paltry 145. In the second innings while the other West Indians faltered, Headley would bat as if he was carrying on from the first innings to notch up 114, marking his second century of the match.

Given a target of 617 to win the Test, England would fold up for 327 and West Indies would have the first Test victory on their home soil. Despite the double century from Roach and the wickets from Constantine, it would be George Headley’s twin centuries that would get much of the credit for this victory which meant so much to the West Indies.

In the final timeless Test at Jamaica, Headley would register scores of 10 and 223. With his double century in the second innings, he would wipe Roach’s name off the record books after a single Test match. West Indies were 408 for 5, chasing 836 for win at Jamaica, when the match was drawn by mutual agreement. Headley ended the series with 703 runs at 87.87.

The Black Bradman

In 1930-31 when West Indies toured Australia, Headley’s fame spread. After watching his 131 against Victoria at Melbourne where West Indies lost by an innings, Hugh Trumble said that it was the best innings he had ever seen in his 50-years of watching cricket. Given Headley’s growing reputation on the offside, the wily Clarrie Grimmett adopted a leg side line to him in the Tests.

By the end of the tour, Grimmett certified him as the best player through the on-side, notwithstanding the fact that the leggie had spent much of his career bowling to Jack Hobbs and Don Bradman.

When Headley toured England for the first time in 1933 and struck 169 not out in the Manchester Test, A. Ratcliffe, writing in the 1933-34 Cricketer’s Annual, remarked: “His cuts off slow bowling were a strange sight. I had only seen such strokes once when [Frank] Woolley cut Roy Kilner repeatedly to the boundary.”

When England visited the West Indies in early 1935, by his standards Headley had sub par scores of 44, 0, 25, 93 and 53. With the series tied 1-1, the teams came to Jamaica for the final match. George Headley batted for eight-and-a-quarter hours for his unbeaten 270, and then Learie Constantine and Manny Martindale scuttled England out twice with hostile spells of fast bowling. West Indies had won their first ever Test series, and it was Headley who had perpetrated the climax.

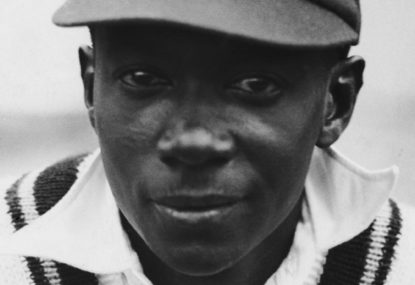

The ‘black Bradman’ in action. (Photo by Central Press/Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

In 1939, in the final Test before the Second World War, with West Indies 1-0 down in the series, George Headley reminded the world of the kind of batsman he was by scoring a century in each innings for the second time in his career, this time at Lord’s. His feat at Lord’s would not be repeated for over 50-years. The tour could not be completed because of the impending war and the team departed for Canada immediately after the Test and landed there the day England declared war on Germany.

Like for a generation of his fellow cricketers, it looked like the Second World War had brought an end to Headley’s career.

In the meantime as Arunabha Sengupta writing in Cricket Country was to remark: “All through the decade, Headley had been a symbol of hope for the black populace of the Caribbean islands.

Jamaican Prime Minister Michael Manley described him as “black excellence personified in a white world and a white sport”. Headley himself was conscious about his African roots in the proudest possible way. When he had entered Australia for the 1930-31 tour, he had put in ‘African’ on the immigration. The dreams of the black communities rose with his soaring deeds.”

It was therefore little surprise that Headley came to be known as the Black Bradman. It remains the opinion of many until this day that with his career Test average of 60.83 and his brilliant batting, he should be reckoned with virtually in the same breath as Sir Don. Others differ citing that the quality of bowling Headley faced in comparison to some others was of inferior quality. It is one of those disagreements that will never have an agreeable conclusion.

A black captain? Gentlemen you must be joking!

One doubts that these armchair expert led discussions about whether he was in the same league as Bradman or not would have ever mattered to Headley. What did matter to him and his fellow cricketers of African descent was however the fact that despite being the best player in the team, the management of the sport in the West Indies would not deign to make him the captain because of the colour of his skin.

Sengupta again: “Without any shred of doubt Headley was the best person to lead West Indies in terms of cricketing skills and acumen. All the West Indian captains during that period had, with their collective effort, managed to equal Headley’s number of half-centuries, but none of them had reached three figures. Yet, Headley and Constantine had to play under these white men of questionable cricketing pretensions.”

After the war was over, George Headley, much to everyone’s surprise was still playing some excellent cricket domestically. It looked like he would get a second chance at what he and his fellow West Indians had dreamt of. And then it happened.

Noel Nethersole, deputy leader of Jamaica’s People’s National Party, applied pressure on the West Indies Cricket Board to appoint Headley as the captain.

George Headley strode out to toss with England’s stand-in skipper Ken Cranston at Barbados in January 1948, in what would be a landmark moment in the history of the black people of the West Indies.

But, that single Test was all that Headley would ever play as the appointed leader of his side. A perplexed Wally Hammond was led to remark, “Headley is by far the most outstanding player as well as the most experienced cricketer… and I do not see why he is not given unqualified control of the team for the whole series.”

It would take another eleven years before a certain Frank Worrell would become the first full time black captain of the West Indies.

The legacy of George Headley

George Headley’s career lasted a remarkable 24-years from 1930 to 1954 when he played his final Test match in his home town of Kingston. This made his career a touch longer than Sachin Tendulkar’s. Where Tendulkar played 200 Test matches in that period, Headley managed only 22. But he packed some serious punch into that career.

His rate of scoring centuries, of one in every four innings, is bettered only by Don Bradman. Tendulkar in comparison scored one every 6.45 innings. Headley scored 29 per cent of his country’s runs in the Tests that he played, Bradman’s number was 27 per cent.

But the importance of George Headley lies not in the number of Tests or how often he scored centuries but in the impact that he had on the cricket and the psyche of a loosely knit bunch of islands with independent political geographic and national identities, joining hands to play their favourite sport as one sporting nation.

Manley and Symmonds in their treatise on West Indian cricket summed it up when they wrote that “Headley became the focus for the longing of an entire people for proof – proof of their own self-worth and their own capacity. He was black excellence personified in a white world and in a white sport”

At a time when cricket was still ruled by Britannia even if the waves had repelled their claim, a black man, descendant of slaves, in a nation governed by white men, stood tall and not only drew comparison with the greatest cricketer who ever walked the earth, but walked out on equal terms for the toss in a Test match as a leader of his nation’s greatest sporting team.

In cricket as in life, there could not have been a greater legacy George Headley could have left behind.