It is a given that national unions strive to improve and maintain the ranking of their Test sides, because they (rightly) assume that fans want World Cup success, and teams that play competitive, attractive rugby in the years in between. This demands the retention and availability of the best players, and that the pull of increasingly elevated pay packets in the northern hemisphere is countered, via focus and funding for the elite tier of the game, primarily through the protection and enhancement of broadcasting rights revenue.

At the other end of the spectrum are hard-working rugby people who have become frustrated by the neglect of schools and club rugby, a lack of appreciation for their efforts and the failure of national bodies to direct sufficient resources to ensure the attraction and retention of children to the game and to maintain the fabric of club rugby.

So frustrated that some of them would prefer to see the elite, professional administration of the game collapse, no matter the consequences.

Brett Papworth (r) has grown tired of SANZAAR.

Ex-Wallaby Brett Papworth is one of these, last year imploring the ARU (now Rugby Australia) to “Tell SANZAAR that it’s over, and if it costs us money to get out, then who cares, because it is currently being wasted on the wrong things anyway.”

“The simple fact is that we, the rugby public, don’t care anymore.”

Meanwhile the ‘sensible centre’ wonders why rugby administrators – national, state and club – struggle to find a happy medium where the primary objective is to simultaneously ensure the health of elite, professional rugby and grassroots rugby, and to ensure that free interaction and engagement between the two occurs seamlessly.

The situation faced by cash-strapped rugby administrators in any country that isn’t England or France is far more nuanced and difficult than many fans care to credit them. But should that excuse an inability to identify the issues that matter most to people who play and support the game, and to communicate with them in a way that informs and engages them, rather than antagonises?

The following excerpts from the book speak to this discordance:

Unsurprisingly, it is money that is at the heart of the change. Amateur rugby was an equalizer. Some from outside of England and Australia might see this as ironic because of rugby’s reputation as a private school pursuit, but the reality is that rugby has been predominantly classless. Where every participant, from club president down to a lowly fifth-grade player, from masseur to the mothers, wives and girlfriends cooking meals in the kitchen in exchange for a mention in the captain’s speech, did what they did for no recompense. Whether a club was the hub of a small country town, or located in a major city, the structure, operation and way of being was essentially the same. All of it manned by, and reliant upon, volunteers.

As we’ve heard from David Humphreys and others from that era, the early days of professional rugby amounted to little more than players receiving money for doing what they did when they were amateur. Train, play and drink in high rotation. For the average club member and fan of the game, this aligned with their notion of what professional rugby meant; a bit of cash for the players but no fundamental change to the game itself and the way they engaged with it.

In the two decades since the advent of professionalism that notion has been well and truly blown out the water. One key aspect was determining which parts of the game were professional and which were amateur; how far the money trickled down if you like. National unions were immediately required to act and operate as commercial enterprises as they transitioned from amateur governance structures, often having to work through and around people who had given years of service but who lacked the skills or experience

for this new commercial world. Provincial unions mostly followed the same path, often with difficulty, their boards full of club delegates, amateur in every sense of the word. Below them, clubs struggled to determine where they fitted in, many discovering that the notion of raising money to pass it straight on to players was pointless, given that for their better players, there was always a club in the next suburb, town or valley willing and able to pay more. Other clubs decided that local bragging rights justified stumping up cash to keep the best players within their fold.

The early days of professional rugby amounted to little more than players receiving money for doing what they did when they were amateur. Train, play and drink in high rotation.

The profit-and-loss account of a typical amateur rugby club, presented to the AGM once a year by the honorary treasurer, was something easily understood by club stalwarts. Revenue came from player subscriptions, perhaps a local sponsorship or two (although these were more usually for services in kind as opposed to cash), raffles and bar takings. A home win in a big match often meant the difference between a new set of jerseys for a junior team, or squeezing another year out of the old ones. New or renovated clubhouses were built by volunteer labour, often funded by the issue of debentures, honoured by bricks in the foyer bearing the names of proud contributors.

The impact of professional rugby on these clubs’ financial accounts came mostly on the cost side; match payments to keep leading players at the club, and a full-time manager to run the club were the start but not the end of it, as clubs hesitantly looked to each other for a benchmark in how to operate. Where things fell down was the scale of the cost increases, which weren’t matched on the revenue side. Clubs found that the captive market for meat raffles was finite and that the scope for this type of fund-raiser was now insufficient to make an impact on rapidly rising expense lines. Further, as more rigid drink-drive law enforcement, and better TV coverage began to entice people to stay at home more, and player numbers began to shrink, particularly in the regions, clubs struggled to maintain their revenue bases let alone grow them.

The concept of the volunteer didn’t easily co-exist with professionalism. Club members on the end of a broom or a paintbrush, or doing their shift behind the bar, did so willingly, for the love of the club, when all of them were in the same boat. But putting in the same volunteer shift, alongside someone doing exactly the same thing, but who was on a salary? Well that didn’t make a lot of sense to most people.

For the majority of rugby clubs there was no template or expert consultant provided to help them work through the transition phase; essentially they were left to sink or swim. The only realistic solution, which some figured out faster than others, was to stay amateur. Rugby might have become professional, but not all rugby could be so. New Zealand Herald journalist Dylan Cleaver, in his excellent online series The Book of Rugby, quoted Greg McGee – among many things Richie McCaw’s biographer — who said, “Professional rugby has galloped away from grassroots and is more or less part of the entertainment matrix now. Again, rugby is reflecting what is going on in New Zealand. To me, it’s never been a leader. In some respects rugby clubs remain the glue that binds communities but it has never been a leader of societal change.”

You can’t run a rugby club on sausage sizzle revenue anymore.

The formal establishment of a professional tier, a level of competition for elite players in all major countries, below international level became the basic line of demarcation. That sounds like a clean and tidy natural evolution—save for those bankrupted or distressed clubs who simply ran out of members, or too late discovered they were too small to act big in a world not meant for them. Accordingly the framework for what is professional and what is amateur rugby has mostly become known and understood. That there are some clubs still today with identity issues or tip-toeing through an amateur/professional minefield speaks to the blind determination of some club administrators to deny the inevitable and, also perhaps, feed off a victim mentality.

One of those pockets exists in Sydney club rugby, where proud clubs that have been ‘top dog’ for over 140 years fought bitterly against the idea of being afforded a comparatively lowly, amateur status. Instead, they have chosen to maintain a semi-professional competition that many members believe represents the rightful development tier for Australian rugby when compared to the manufactured model of the NRC. Theirs is effectively affirmation of the English model, where clubs assume precedence over provinces and regions, but without sufficient numbers of solvent, competitive clubs, without a large enough audience or any television rights revenue, and with the leading players contracted centrally through the ARU, they remain impossibly wedged.

Interestingly, Sydney’s premier club rugby competition, the Shute Shield, has been shown on commercial free-to-air television (one match per week) since 2015, although this comes at a cost; the Sydney Rugby Union (SRU) guaranteeing the broadcaster, Network Seven, A$300,000 for 2015 and A$500,000 for 2016, as opposed to receiving payment for the content. To make matters worse, while it was the SRU who negotiated the television arrangement—effectively owning it as their deal—they discovered that they did not have the means to pay for it, and the ARU was asked to bail them out. At the same time, a number of those same clubs were actively conspiring to sabotage the ARU’s fledgling NRC competition – yet another bewildering example of how, when the lines between professional and amateur rugby administration become blurred, nothing good comes of it.„

Australia’s current rugby angst is not dissimilar to that experienced by Wales, a rugby nation that struggled to adapt to professionalism and has paid a heavy price ever since. None of this should have come as a surprise, given that the template provided by British football, a game professional for 110 years longer, is now being mirrored by professional rugby, albeit on a smaller scale.

In their excellent account of the demise of the once mighty Welsh valleys rugby club Pontypool, The Good, the Bad and the Ugly: the rise and fall of Pontypool RFC, authors Nick Bishop and Alun Carter outlined myriad factors contributing to the ‘Poolers’’ descent into relative obscurity. But, above all of the stubborn club personalities refusing to adapt to a changing world, the Welsh Rugby Union (WRU) adopting a regional strategy at the expense of traditional clubs, the Newport rugby club refusing to embrace other clubs and redrafting the boundary of the Gwent region to a small circle of land straddling the M4, the single factor that most contributed to, and indeed ensured, Pontypool’s demise was the economic devastation which occurred to towns and mining communities in the valleys. The economic haemorrhaging of the southern valley towns in the late 1970s and 80s affected families at every level, and resulted in a diminishing of local manufacturing and community pride, and de-population to an extent that many of the towns and villages, their high streets and their rugby clubs, can never again be what they were.

Pontypool were a Welsh powerhouse in their heyday, as seen here in a 1984 clash with the Wallabies. (Photo: Allsport UK/Allsport)

The painful irony is that it was the exact opposite that laid the foundation for what was perhaps Wales’ greatest golden era, in the early 1970s. In his rugby history, Huw Richards described the social change in post-war Wales and how Barry John, Gareth Edwards and Gerald Davies, legends all of them; “…were born into mining families in south-west Wales between 1945 and 1947, grew up in the new dawn of publicly-owned pits and free healthcare and fulfilled parental dreams of escaping the pit via the classic Welsh working-class route into teaching.” What the earth giveth, the earth taketh away.

Whatever one’s opinion of Baroness Thatcher, neither she or her government, or macro-economic forces alone, can wear all of the blame for the decline of Welsh rugby, at least not in every club’s case. By its very definition, professional sport implies the generation and distribution of money; derived from the sport, for the sport and because of the sport, and it is self-evident that where there are more people there is more economic activity and a bigger market, at every level; club, provincial, national and within the sport itself. What follows is the greater likelihood of financial success, and following from that, success on the field. In places where economic activity surges, communities spring up and infrastructure, including new sports clubs, follows. When boom turns to bust, often as suddenly as it arrived, the dissolution of those sports clubs and the role they play in the social fabric of those communities is inevitability more drawn out and painful. A rugby club with ample manpower for two teams finds itself at the start of next season with barely thirty players — then twenty the next. Then, with a few injuries and another couple of transfers out of the region, it begins to default matches, unable to field a side, despite long retired club stalwarts pledging to come out of retirement to save the club. To imagine that professional sport can be successfully undertaken and managed in such a declining environment is fanciful.

Whatever one’s opinion of Baroness Thatcher, neither she or her government, or macro-economic forces alone, can wear all of the blame for the decline of Welsh rugby.

To that end, Goldblatt’s tour of the UK, while not at all surprising, is drenched in misery. Vivid images abound of small football grounds, once the pulsing heart of towns and cities all across the UK, now decrepit, closed due to health and safety concerns, or else host only to a few meagre hard-core fans and family members, watching their loved ones slog it out in a lowly semi-professional league.

Rugby’s version of the same is beautifully captured in a pictorial essay by Tom Jenkins, with words by Donald McCrae, published in the Guardian in 2013, documenting the leaching of the spirit from the Welsh game, as a direct outcome of economic flight and societal changes which no longer provide enough able-bodied and/or enthusiastic players and supporters to sustain healthy local rugby clubs. It is as if the saying ‘a picture tells a thousand words’ was invented for Jenkins’ portrait of Maesteg rugby coach Richard Webster, captured alone in a cold, dank changing room, in equal measures steely determination and despair, wondering how and where he would be able to find enough players to field a team for Maesteg’s next fixture.

Founded in 1877, with a history typical of many other similarly-proud Welsh provincial clubs, Maesteg barely limped through the advent of professional rugby and the imposition of regional teams by the WRU and, aside from a brief sojourn into the Welsh Premier Divison in 2005, oscillated around the nether regions of WRU Division One West Central. As if things weren’t difficult enough, a modest clubhouse refurbishment was destroyed in an arson attack in 2013, along with precious club memorabilia. Then in 2016 the club lost an unfair dismissal claim after a barmaid accused of stealing money was found by a work tribunal to have been “deeply violated” by the actions of the club’s bar manager, calling her a “ho” and a “thieving bitch” on Facebook. The club was lumped with a £6600 fine, plus payment for loss of wages; money it could ill afford to lose. Nothing if not resilient, the club forged on, the senior squad enjoying a winning season in 2016/17, and fielding teams at under 16 and under 14 level; providing at least some glimmer of hope for continuity into the future.

Courtesy of its geographic location, a little to the east of Swansea and Neath, Maesteg today serves as a ‘feeder club’ to its regional Pro 12 club, the Ospreys, although with the advent of player pathways through youth academies coupled with overseas signings, the chance that a player ripping it to shreds for Maesteg one week might be parachuted into the Ospreys the next is nil. Simultaneously this represents the necessary gulf between amateur club and professional rugby, and the disconnect between the heartland clubs and the regions that were imposed upon them; issues that, thirteen years later, are still suffocating Welsh rugby.

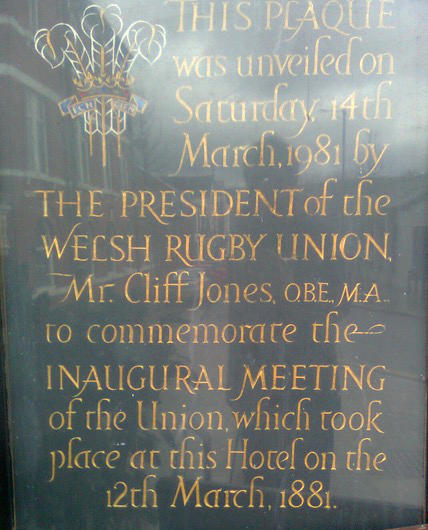

Neath is where I find Bishop; a lanky, laconic Anglo-Welshman with a foot in both camps, a rugby analyst and writer widely-regarded as one of the sharpest intellects in the game; a strategic playmaker trapped in a lock’s body. We walk to the Castle Hotel, a historic site where the inaugural meeting of the Welsh Rugby Union took place on the 12th March 1881. Our nod to history doesn’t extend to the bar however; Nick orders a flat white and I an Italian beer; both unlikely to have been on the menu back then. Settling in for the afternoon, he points to clear differences between Wales and England and France which are at the heart of Welsh rugby’s woes.

The historic plaque outside the Castle Hotel. (Image: Nick Bishop)

“Post-professionalism, in Wales they started by trying to walk upside down, where they had benefactors in the game, who have since left, leaving behind a black hole in terms of finance. As a result, the only person or institution left in the game in Wales who can afford to spend significant money or buy leading players is the Welsh union itself. By comparison, in England and most definitely in France, those benefactors are still there. So there is this very strong co-dependency between the Welsh regions and the union; where if the union was to withdraw its prop, the regions would collapse.

“Welsh rugby is still recovering from that situation, where it put the national side first and club rugby a very definite and distant second. It put all of its marbles into one basket, very similar to what Australia did. Both countries have really depended on international success, Wales in the Six Nations and Australia in the Bledisloe Cup and World Cups, and tried to be successful first in those arenas to bring in the money; Wales mostly so it can pay off the debt for the National Stadium. Unfortunately, not a lot of that money has got recycled back into the layers below the international game. That’s why in Wales a lot of the traditional clubs have gone to the wall, or got to the point

where they can only field one side on a Saturday instead of where they used to have nine or ten sides.”

Bishop is clearly perplexed by a situation where, given the dearth of money throughout the game in Wales, much of what there is goes to waste; “In Wales there is still no clear boundary between the professional game and amateur rugby. You get cases of clubs three and four divisions down where players expect to be paid, and often are; in some cases, lots of money. There are clubs in the championship, like Merthyr, who were taken over by Sir Stan Thomas (brother of Cardiff Blues owner, Peter Thomas), where he immediately started treating it like a professional institution. Sure, it might have been nice for the locals to be promoted up a division but, at the end of the day, what does that really achieve? You’re not going to get benefactors for every town or little village in Wales and you’re certainly not going to get the Welsh Rugby Union to support semi-professionalism for clubs at that level. For countries like Wales and Australia, who have limited funds, it surely has to be the aim to clearly separate professionalism and amateurism and not to mix the two.

“The EPL and the rest of football has proven that you can really only have one elite, professional level, which attracts sponsorship, media revenue and wealthy owners, and a base amateur level.”

“The EPL and the rest of football has proven that you can really only have one elite, professional level, which attracts sponsorship, media revenue and wealthy owners, and a base amateur level. Where you try to run a professional model somewhere in between, the result is that clubs go to the wall and communities are devastated as a result; because someone else will always have more money and therefore either better players, or else they will force you to buy better players that you can’t really afford.

“The USA figured this out long ago; almost all of their sports have non-existent, or at least a very thin, professional tier below the top level. But rugby, in Wales, Australia and the lower divisions in France, has yet to figure this out; possibly because professionalism in rugby is still in its infancy.”

Hindsight has shown how, even if the ham-fisted manner in which the WRU forced the regions onto the clubs is set aside, regionalism works best where there is an existing provincial structure that stakeholders are already familiar with, such as in New Zealand and Ireland. This was vividly captured in Ronan Cassidy’s excellent 2011 documentary Munster Rugby; A Limerick Love Affair, a testament to the power of regionalism where it is founded in history and authenticity. But when regionalism is imposed from upon high, with disregard for historic affiliations and traditions, the effect is to disenfranchise the grassroots; the volunteer club workers and small-town club supporters. Mick Dawson, CEO of Leinster concurs.

“The IRFU just polished a provincial system that was already there. The provinces aren’t abstract or constructs, they have hundreds of years of history of being divided along those same lines. What Wales did was create winners and losers, and pitch clubs together who weren’t necessarily a natural fit. Scotland is somewhere in between; not the animosity and despair of Wales, but they were slower to understand and adapt to professionalism than Ireland.”„

So what of New Zealand, rugby’s undeniable benchmark for elite professional performance? Have they struck the right balance between professional and grassroots rugby?

Certainly it is no wonder that they played a very firm hand in demanding that South Africa and Australia reduce their Super Rugby franchises, in order to shore up the value of broadcast rights heading into the next round of negotiations, which are likely to begin later this year.

With SANZAAR’s ability to fund New Zealand rugby into the future uncertain, NZ Rugby has sensibly sought to cement commercial relationships with global brands such as Adidas, Tudor, Vodaphone, AIG and Amazon, in order to be as self-sufficient as possible. There are dangers, however.

A Weekend Herald editorial, in June 2017, similarly warned “Provincial rugby, meanwhile, depends increasingly on grants that come from the top, earned by the All Blacks. NZ Rugby has become an extremely monolithic enterprise, owning even the regional Super Rugby franchises in this country. The dangers are obvious. The future of the game depends entirely on the wisdom of a few such as (Steve) Tew. There are no competing centres of decision-making as there would be if the Super Rugby franchises were independent companies.”

All Blacks sponsorship revenue may be more important to New Zealand rugby than we realise.

Rob Nichol has a different slant, seeing the All Blacks’ sponsorships and intellectual property as divorced from the grassroots of rugby. “They say the All Blacks fund it (rugby in New Zealand). They don’t. It’s the people who fund it: it’s the people who choose to buy the sponsors’ products, who choose to buy a broadcast subscription, who choose to go along to the game. The community funds the game, make no bones about that.”

Although approaching things from different perspectives, Cleaver and Nichol are essentially saying the same thing; that the future health of New Zealand rugby depends not on the success of the All Blacks nor their ability of their brand to generate money, but on how well rugby engages and connects people at the community level. Nichol again; “Our commercial future must be tied to a more community-focused pitch, which has to be about ‘what is the opportunity provided to me and my kids to be engaged with a sport that helps my personal development, provides personal growth opportunity, which teaches camaraderie and teamwork and which is good for my health and fitness?’ We need parents to be comfortable that rugby teaches characteristics and values that they want their kids to be involved with. If we can get better at teaching kids at age 14 and 15 that these are the reasons to stay engaged with rugby – not just because you might make the All Blacks and be famous and make lots of money — then their expectations will be set right, and they’ll be far more likely to stay engaged into adulthood. But if we keep sending messages that are dominated by the All Blacks and professional rugby, then we risk teaching kids that it’s only worth engaging with rugby at that level, and that’s where we potentially lose what underpins the game as a whole.

“We need to have a massive rethink about our commercial strategy and ask ourselves ‘what is the real vision about what drives the commercial side of the game’, and it must be the willingness of the community to engage with the game. If we lose that then we’ll be out the back door.”„

To ensure the long-term health of rugby in the four SANZAAR nations, it is crucial that a far stronger connection between the professional and amateur games is forged.

But reports a few weeks ago that Beauden Barrett has been offered NZ$3.4m per year to play for a French club demonstrate how the ‘pull forces’ from the north are not going to abate any time soon, and illustrate how difficult it is for senior administrators to get the balance right.

In a global marketplace, any romantic ideal that these external pressures can simply be waved away, and grassroots rugby embraced at all costs, is fanciful.

The truth is, whether a club stalwart, parent, professional player, Rugby Australia executive, broadcaster or casual fan, we are all in this together.

Professional rugby needs grassroots rugby just as the grassroots needs a healthy, financially viable professional game. As much as the chequebooks of English and French clubs, it is parochialism and self-interest (and in Australia, muddying of the waters between national and state responsibilities), that is the enemy; all of which must be overcome if the future health of the game is to be secured.

Written by Geoff Parkes

Geoff Parkes is a Melbourne-based sports fanatic and writer who started contributing to The Roar in 2012, originally under the pen name Allanthus. His first book, A World in Conflict; the Global Battle For Rugby Supremacy was released in December 2017 to critical acclaim. Meanwhile, his twin goals of achieving a single figure golf handicap and owning a fast racehorse remain tantalisingly out of reach.

Editing, design and layout by Daniel Jeffrey and Stirling Coates

Image credit: All images are copyright Getty Images unless otherwise stated.