They have money by the bucketloads, without any pinpricks of conscience to stop them spending it. At least, that’s one popular view of the English and French clubs looking from the other side of the fence.

In the Southern Hemisphere, they are frequently seen as greedy self-aggrandisers, ruthlessly picking off the best talent from Australia, New Zealand and South Africa without a thought for the state of the game in those countries. They do it because they can.

Such a view is not entirely fair, but more importantly, it is no longer accurate either. In an excellent series of articles in the UK’s Guardian last week, Paul Rees and David Conn outlined the very real financial problems facing the professional clubs in England.

In their core piece, Rees and Conn published a short-hand version of the latest Premiership financial report (for 2016-17).

Of the 12 clubs, only Exeter Chiefs are in the black. Losses for the others for the financial year range from anything between £0.81m (Sale Sharks) to a colossal £8m (Worcester Warriors).

Wage bills are very high by Southern Hemisphere standards, ranging from the lowest (Sale at £6.5m) to the whopping £17m paid out by Wasps. Wages average out at more than 60 per cent of total turnover at the clubs, and, in the case of Worcester, actually exceeded turnover for the year at 101 per cent!

Combined losses were £28.5m and are predicted by insiders to rise by a further 20 per cent in next year’s accounting. All of the increases in turnover are being eaten by higher wages. Even though Leicester own their ground and have increased the capacity at Welford Road to a maximum of 26,000, they are still making a loss of just under £1m per annum.

As Tigers’ chief executive Simon Cohen says, “Clubs are no better off than when the Premiership started 20 years ago and that is a real shame. The percentage of extra revenue over the years that has gone to players has put clubs in a position where it has been difficult to invest in other areas of the game. You want to spend more on infrastructure and the match-day experience for fans but you are less able to do it because of the amount going on wages.”

In other words, the clubs still have to borrow money in order to improve their essential facilities, despite everyone (bar Sale) now owning the stadiums at which they play. Without the backing of wealthy benefactors willing to write off debt, they would simply be unable to function.

By far the richest institution in the English professional game is the RFU, and their revenue is built around international matches. In 2016-17, the RFU harvested revenue of £184.9m (more than all the Premiership clubs combined), 20 per cent more than the previous year with World Cup impacts adjusted.

(AAP Image/Dave Hunt)

£93.6m was profit used for reinvestment in the game, another £3.9m was profit retained. Ticketing and merchandising were both significantly up, and the RFU now enjoys net assets worth more than £215m, with cash reserves of £18.5m.

The club game in England urgently needs even more financial support from its own Union, but still cannot bring itself to ask for it. Further help would probably mean ceding meaningful control of player contracts to the RFU, the kind that the WRU and IRFU already enjoy in Wales and Ireland; the kind that should have been in place right from the beginning when rugby turned professional back in 1996.

Contractual control of their assets is the very last thing the clubs want to give away, so the situation has reached a stalemate. An uneasy partnership in which the elephant in the room is neither seen nor heard.

For the international rugby star from Australia, New Zealand and South Africa, the clear message is, ‘Enjoy the good times while you can’ – because they are unlikely to last for much longer, at least in their current form.

The relationship between the English and French clubs who run their own competitions and the unions who administer the international game is becoming a farce.

The latest episode requires Tatafu Polota-Nau and Matt Toomua to fly halfway across the globe to appear for the Wallabies in the first two rounds of the Rugby Championship, then fly all the way back again for a single club match in Exeter, before returning to Australia for a game the following week against South Africa.

Both players may have to rinse and repeat at least two or three times more, in destinations as far afield as Japan and Argentina, before the end-of-year tours commence.

(Photo by Cameron Spencer/Getty Images)

The addition of the Bristol Bears to the English Premiership has upped the stakes further at a time when the rest of the Premiership is getting used to life underneath a ‘flat cap’ – a fixed salary cap until the end of the 2019-20 season. Billionaire owner Steve Lansdown is keen to make his mark and has created rugby’s first £1m per annum player in the shape of All Black Charles Piutau. It is an uncomfortable precedent in times of austerity.

The Bears have a Samoan coach in Pat Lam and their team is based around a core drawn from the Pacific islands, New Zealand and Australia – John Afoa, Chris Vui, George Smith, Stephen Luatua and Jack Lam up front, Nic Stirzaker, Alapati Leuia, Luke Morahan and the Piutau brothers behind.

On a rousing Friday evening in front of 27,000 people, Bristol overcame West Country neighbours Bath by 17 points to 10 to win their first match back in England’s top club tier – with Luatua (on defence) and Morahan (on attack) showing what southern quality money can buy.

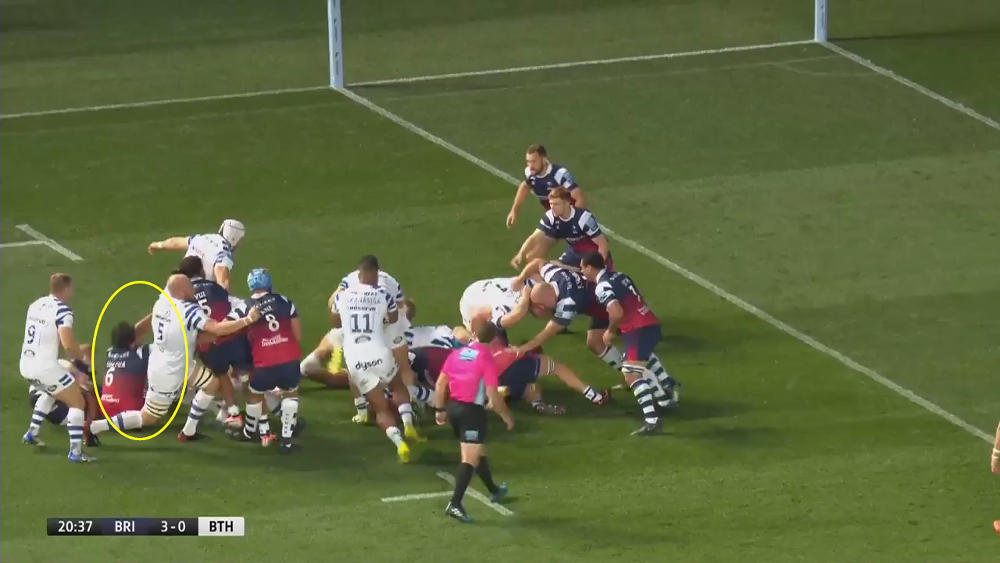

In the light of last week’s article on Lukhan Tui, Steven Luatua’s performance illustrated what superior work-rate and quick reloading times for a number 6 can mean in terms of real impact on the game. With Bristol struggling to keep a foothold in the first quarter, it was Luatua who produced four turnovers in that period to right the ship.

He led the defence opposite first receiver (the most physical of all spots) and even found time to call the lineouts:

That is a straightforward example of Luatua’s power in the tackle. His multiple involvements were even more impressive:

Luatua first forces Bath number 8 Taulupe Faletau to pass to his winger in an unfavourable situation, then slingshots around him to tackle Semesa Rokoduguni and dislodge the ball, then re-rucks over the turnover – three important involvements in the space of six seconds which enable Nic Stirzaker to relieve the pressure with a long kick.

Here Luatua makes the tackle at the start of the sequence, and within two phases and seven seconds he is back on his feet to set the line-speed and make another, pressuring the Bath receiver into a forward pass.

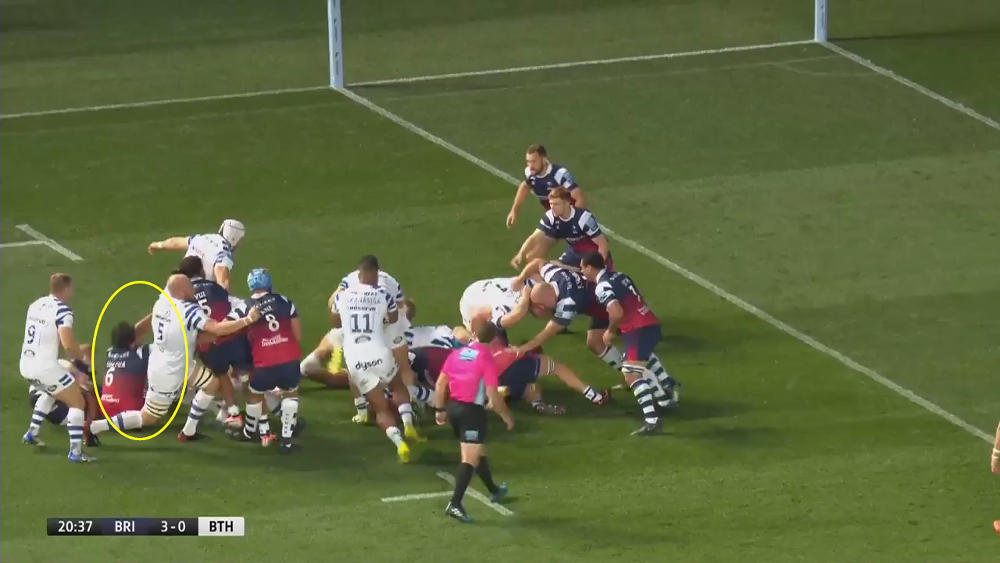

The final example comes from a Bath lineout drive close to the Bristol goal-line. Luatua’s first task is to disrupt the maul by taking on Bath’s two biggest blockers, Dave Attwood and Matt Garvey:

A few seconds later he is up on his feet and reloading into position opposite the first receiver, cheating up on the offside line to take an interception and neutralize the danger:

Luke Morahan meanwhile was clearly the most potent outside back on view from either side. The last of his three clean breaks resulted in the score which decided the match in Bristol’s favour:

At 6’2 and tipping the scales at around 100 kilos, Morahan has the size and speed associated with the best Australian back-three players. He has the workrate and understanding (wrapping around the ball-carrier in the second example), the fend and offload (in the final scoring play). He can play winger or fullback with equal efficacy, and he played outstandingly well for the Wallabies on the only occasion he was selected to start a game (against France back in 2016). What’s not to like?

Summary

The ashes Australian supporters are heaping on their heads after the first two rounds of The Rugby Championship may still be glowing embers, but misery is by no means confined to the Southern Hemisphere.

The player drain from the south to the north is on a timeline, and there is little sign that English clubs will be able to balance their books in the near future – if ever. Perhaps the only question is when the current balloon of spiralling wage bills will finally burst.

Unless the spirit of co-operation between the richest organization in professional rugby (the RFU) and the Premiership clubs extends to include national or dual contracts for the players, in which the Union has first call on their services, there is little prospect of improvement.

There is little likelihood of that happening – but only then will the international and club games truly reunite.

Players like Steven Luatua and Luke Morahan go north primarily to achieve financial security for their families in the second half of their careers, but both are still in their playing prime.

If he was still in Australia, I have no doubt Morahan would be challenging for a starting place in the current Wallaby line-up ahead of Marika Koroibete, and Nic White would be the back-up 9; Tatafu Polota-Nau and Matt Toomua would not be on a comical shuttle tour between Australia, Argentina, Japan and the UK.

It’s time for rugby to heal itself worldwide, but in order for that healing to occur, private ownership might have to take a back seat, and realize that the grass on its side of the fence is never going to grow quite as lush and green as it wants.