‘How do you know Australia exists? I mean, how do you really know it is real? On what basis do you believe in Australia?’

Several of my high school rugby coaches tended towards insanity, but one particular coach was clearly over that blurry cognitive line. Mr Wolhuter liked to keep us on edge.

In his defence, we were a tricky mob to manage. Floppy-haired privileged ‘English’ boys at the leafy old red brick school in the shadow of the rump of Table Mountain, convinced Mandela’s freedom would change everything, oversexed, undercooked, and wild as hairy itchy baboons.

Mr Wolhuter taught woodworking, too. Make a mistake in measuring your cut and you would find yourself in a small chalked circle on the floor, the other boys watching, as Mr Wolhuter practiced his lofted cover drive with the bat he had nicknamed ‘Gerrie Germishuys’ and gave you the good news: ‘If you can stay in the circle, I’ll stop hitting you, hey.’

We soon learned it was better to score sixty or seventy percent on a test than ninety-nine, because Mr. Wolhuter’s brain became incensed by such a narrow brush with perfection.

‘Into the circle, man,’ he would say to the boy who missed just one question. ‘I need to practice my midwicket drive.’

He never scored a half-century, but Mr Wolhuter sported a decent batting average, probably about 23.8 runs.

His absurd interrogation about the existence of Australia stuck with me forever. Why did I believe in Australia?

My parents had friends who claimed they had gone, but so few ever returned, and the stories they told, and the images they explained, as we watched a slide show on the lime-wash brick of the living room wall defied easy comprehension.

The flight schedule boggled the mind: a time travel plot. Even the animals made no sense.

Mark Twain wrote: ‘Australian history does not read like history, but like the most beautiful lies.’ D.H. Lawrence seems to have concurred: ‘You just walk out of the world and into Australia.’

Indeed, if a fictional country were to exist, Australia was a fine candidate: so far away, with so many odd creatures and the Bee Gees, too. The anomalies of Australia’s animal kingdom puzzled Charles Darwin so much he wondered if there had been two creators, a traditional deity for the northern, orderly hemisphere, and some other god who thought up marsupials and Australia.

Rugby observers from the north still wonder this when they behold the wonders of Pooper, and question the evolution of the game from its origin to this new and strange species of football.

Beauden Barrett of the All Blacks is tackled by Michael Hooper of the Wallabies (Photo by Matt King/Getty Images)

Even using the excremental name ‘Pooper’ on serious sport shows or articles reminds us Australians are among the most irreverent of peoples. Travel writer Paul Theroux put it this way: ‘The Australian Book of Etiquette is a very slim volume.’

Aussies seem to say what they mean, in the way they bloody feel. Take the timeless lyric of Bon Scott, for example: ‘What I want, I stash. What I don’t, I smash.’

Wallaby coach Michael Cheika would say ‘A–f—ing–men’ to Theroux and AC/DC. He has never seen tradition as a value to be preserved. During the 2015 Rugby World Cup, he noted: ‘We’re not all guys who are camped out by the billabong with a cork hat.’

Once more, there is a strange reference for non-Aussies. Hats with swinging corks were reputedly worn by jolly swagmen in the Outback to ward off pesky flying insects. Perhaps this is the ultimate rugby philosophy of Cheika: maybe a cork hat is a fullback who kicks or a swagman by the billabong is a Number 8 who links, and he has a newer dream.

Australia is seen as a new place, a young and fair nation, a place of last resort, a practice ground for apocalypses. The founding myth is of rejection, being outcasts. Risks can be taken. Bill Bryson wrote: ‘Australians are the biggest gamblers on the planet: … the country has less than one percent of the world’s population but more than twenty percent of its slot machines.’

Fellow former British colonists, the Americans, may beg to differ with Mr Bryson, but aren’t Australians better at being American than Americans are, nowadays? Rupert Murdoch basically redesigned blind American patriotism for the masses, and set the stage for the MAGA creed.

Hell, Baywatch was filmed in Sydney for a few seasons, in The Matrix, Sydney pretended to be Chicago. Now that I write this, I think: maybe when we talk of ‘Australia’ we are really speaking of Sydney. We go back to Twain. When he came to Sydney in the late 1800s, the American humourist fell in love with Sydney Harbour, but when he expressed his admiration to a local dockworker, he was told: ‘God made the Harbour, but Satan made Sydney.’

Of course, Queenslanders may agree with that dockworker, and sometimes it seems from outside the Sydney metro area that certain Waratahs are the priests in Cheika’s new rugby religion, but team selection and theology are always thorny subjects. I did not know all of that, back then, as I tried to answer my rugby coach’s rhetorical question.

Michael Cheika calls on a higher power (Photo by Hannah Peters/Getty Images)

The muscular Mr Wolhuter made me captain of the Under 16A team, despite (or because of) putting me in his chalk circle more than any other student, and as we ‘discussed’ an opponent and our game plan for the Saturday morning match, he asked me how I knew Australia existed.

At first, the question seemed preposterous. Why would I bear the burden of proof of something so universally accepted? I mean, there was an actual miniseries about the colonial era in Australia on fledgling South African television in the late Seventies: Against the Wind. How could this elaborate history be invented and confirmed by so many?

In the series, Mary Mulvane, a redheaded Irish girl, is sent to New South Wales for seven years for trying to take the family milk cow back from the British who seized it for failure to tithe a proctor. Every week, I watched her journey across the sea, her hardships, her romance with a taverner and fellow convict, and their long fight with corrupt military rulers.

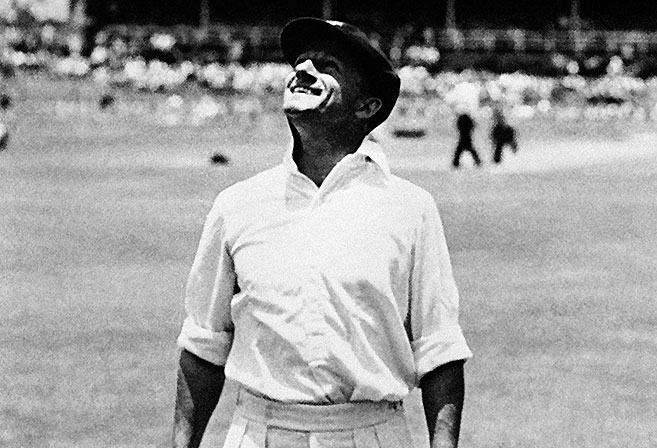

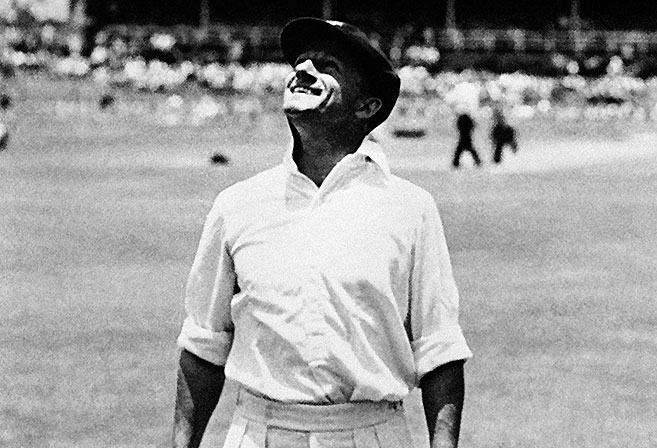

There must be an Australia, I reckoned. It’s on the bloody map, Uncle Oscar went there on holidays, I can see detailed lists of Don Bradman’s batting performances, which would require so many South Africans to be complicit and defeatist collaborators in decades of lies, and then there was this show, Against the Wind.

Of course Australia existed – what about Bradman? (AP Photo, File).

But then I realised my mad coach’s method: a team or an idea is built on trust. Belief.

Each argument I made for Australia was a small but vital statement of belief in a person or a thing or an institution; the very goodness of family and love. We convince ourselves something exists because we trust: a song, the news, a book, a story, a map, a friend, or a family member.

A team — the 2018 Springboks or the 2018 Wallabies — which is short on belief in the plan, doubts the plan for the breakdown, does not trust the next man in the set piece as jumpers are flung high in the sky or hookers are compressed into dark scrums without pity. This team cannot win consistently, nor challenge for titles and cups.

I told my coach, the borderline Mr Wolhuter, I believed Australia exists because I did not believe a conspiracy of that size could succeed for a hundred years. But I knew the only real way to believe in Australia’s existence was to go to Australia, and even then, I would have to determine if I was real, if time and space were real, and if reality itself was something I could rely on.

I am still almost sure Australia exists. The Roar is one of those elements of evidence which suggest Australia is real. But I decided to go see for myself, next week, en route to a place I already know is true: New Zealand.

I circled the Test in Wellington as a game I wanted to attend, before the ‘deBokle’ in Mendoza. The bonus will be finally proving to me and old Mr Wolhuter that Australia exists.

Why is New Zealand not also a place in need of rugby proof? Well, the rugby rivalry between the All Blacks and the Springboks is accepted a priori, independent of experience; by mere deductive reasoning, as in pure logic. Would there even be a Bok without an All Black, or vice versa? There are mists of memory surrounding each contest, mythic giants in fields of wonder.

The Wallaby-Bok rivalry is actually far more of an even contest, but requires empirical evidence for fans to believe in it. These two highly dysfunctional national unions go to battle this weekend in Brisbane: green-and-gold versus gold-and-green.

South Africa and Australia, formerly cousins of the British colonies, are essentially tied in won-loss after readmission, and on recent form, identical twins.

In 2017, the teams played a little over 160 minutes without even one point of separation. Sisters were kissed in Perth and Bloemfontein (although this is actually just a normal weekend activity in the latter town). In Australia, a rushed Elton Jantjies drop goal attempt missed the mark, and in South Africa, another miss by Jantjies gave the visiting Aussies the Mandela Challenge plate.

The clock can be cruel in any timed sport. Rugby coaches often want more time. More time to practice, more time to plan, more time to rebuild, more time before results are judged, more time to train; and at the end of Test matches, just a little more time, a minute or two, if they are behind on the scoreboard.

Rugby Australia’s boss, Raelene Castle, conveyed a message to embattled Cheika and the rugby world that there is still time, but not too much.

The next World Cup will come in the blink of an eye for Cheika and Rassie Erasmus and Japanese groundskeepers, logisticians, administrators, and security, but for disappointed players wearing green and gold, and their long-suffering fans in the Land of Oz and the Rainbow Republic, even the two weeks following a defeat can feel eternal.

Time is another one of those ‘things’ we are surprised to learn is not an absolute given. The sense of time is elastic, and not just because of the scarcity as we age, but also for scientific and cultural reasons. I remember a day which taught me much about time, and how we see time.

Not long after Mr Wolhuter’s interrogation about Australia, I cycled past a bus stop on the corner of Tokai and Steenberg Roads, just near the Pollsmoor Prison, where Nelson Mandela was imprisoned; he had recently been transferred from Robben Island.

It was early in the morning. At the bus stop, an old African woman sat, with a proud posture. I was going to school. After school, I had rugby practice. Then, I rode home in the rain. It was late in the afternoon. The same woman sat, at the same bus stop. Waiting. I was a bit worried.

‘Auntie. Do you have the schedule for the bus?’

‘Yes. It is coming soon.’

When I realised her patience with the passage of time, I was stunned.

Our personal experience of time is elastic. For me, then and especially now, waiting seven hours for a bus, patiently, would cause my brain to explode. Erasmus and Cheika may have quite a different view of time, too, at the moment, even if both wish they had a lot more of it.

Which man’s time perception is more real? That question is like asking does an Australian Dollar have more value in South African Rand or is a Rand more valuable in Dollars?

Oddly enough, the idea of a unified clock is quite recent. Time is of course not the same everywhere, physically. Time runs faster at higher altitudes; slightly. Even a few centimetres apart, a clock on the floor runs slower than one on top of a table. There is literally a different time in every point in space.

Yes, the division of days tends to correspond easily in the same region, because of rough similarities of sunrise and sunset. Hours were – for centuries – longer in the summer and shorter in the summer, because dawn and dusk were the fixed points into which twelve hours had to be sub-divided.

But calibrating time into minutes or seconds is modern. Carlo Rovelli, an Italian physicist, wrote last year in The Order of Time, that each town’s clocks in bell tower or church established a local time from the 1500s until almost 1900.

“For centuries, as long as travel was on horseback, on foot, or in carriages, there was no reason to synchronise clocks between one place and another. There was good reason for not doing so. Midday is, by definition, when the sun is at its highest. Every city and village had a sundial that registered the moment the sun was at its midpoint, allowing the clock on the bell tower to be regulated with it, for all to see. But the sun does not reach midday at the same moment in Venice, or in Florence, or in Turin, because the sun moves from east to west … for centuries the clocks in Venice were a good half hour ahead of those in Turin. Every small village had its own peculiar ‘hour.’”

Rovelli points to trains becoming more commonplace and fast in the Nineteenth Century, along with the arrival of the telegraph, as ushering in the ‘problem’ of different time.

“It is awkward,” he writes, “ to organise train timetables if each station marks times differently.” After a ‘universal’ time was rejected, a compromise was reached in 1883 to divide the world into time zones, standardising time only within each zone, with a ‘discrepancy’ limited to about 30 minutes. One of young Albert Einstein’s first jobs was to examine patents to synchronise clocks at railway stations in time-obsessed Switzerland. He soon realised it is impossible to truly synchronise clocks, because time is not the absolute we wish it were.

Rugby is just like time, in a way: a code and a game full of putative synchronicity, with rucks and lineouts and scrums and aerial contests depending on simultaneity or the belief in same. Some players seem to forever have more time and space; watch Dan Carter in his prime and see a man unbounded by clocks or touchlines.

Referees face the greatest ire when they misjudge timing. More rugby words were written in Australia about Israel Folau’s orbit into Peter O’Mahony and the gravity of CJ Stander’s lift than the actual result of the Irish series win.

Folau flies high (AAP Image/Craig Golding)

The Australian national rugby coach is running out of time, say some; others ‘give’ him more. The Springbok coach just ‘started’ his time in an even more complicated synchronisation, even, than the Wallaby job. They are on a collision course along a continuum that starts or ends in Brisbane. nd I am still a believer in Australia: the place, the land, the fabled continent of similes and magpies and larrikins, with the long roads and outlandish claims.

We will let an Aussie have the last word, and it is a verse that welcomes the skeptic, and might even form the basis of belief, at the breakdown in Brisbane or after we all break it down, after:

‘So slide over here

And give me a moment

Your moves are so raw

I got to let you know

I got to let you know

You’re one of my kind.’