In the turbulent wake of the ball tampering scandal, I started re-examining my relationship with the sport I cherish.

Cricket’s values

I’ve posted articles already on the spirit of cricket, ball tampering and sledging.

I stand by my thoughts on how cricket – Australian cricket, in particular – might improve its street cred. But as the Test Series against Pakistan begins, I have found that I retain my passion for Test Cricket.

Now I turn to the happier task of exploring Cricket’s core values. In doing so, embark upon my journey towards exploring whether Cricket has its own spirit; distinct from other sports.

Fighting to the death

It’s March 1984 and I’m 15 years old.

For a mid-Autumnal morning, it’s unusually chilly at my boyhood home in Dural and I’m curled up in bed with my new blue doona tucked beneath my chin. Even with the aid of the doona, I’m still shivering.

It remains dark outside and I don’t have to get out of bed, to go to school, for another couple of hours. But I’m wide awake and my transistor radio is on. I can hear the comforting voice of Jim Maxwell all the way from Port-of-Spain in Trinidad.

It’s the last day of the Second Test against the West Indies and Australia has no hope of winning. The Windies bowling attack is fearsome – including Malcolm Marshall at his fastest and most frightening, Joel Gardner galloping in off his long run and veteran and Wayne Daniel, older than he once was but as fast as ever.

Australia started the day with seven wickets in hand. Kepler Wessels, Wayne Phillips and Greg Ritchie were despatched the previous evening. Australia still requires a daunting 160 runs to cause the West Indians the inconvenience of having to bat a second time. The Aussie’s position is precarious – lose some early wickets and an innings defeat looks a strong possibility.

Things proceed okay for a while as Captain, Kim Hughes, and nightwatchman, Tom Hogan, accumulate another 60 runs and, suddenly, the Aussies look more comfortable. If they can just find a way to eke out another 100 runs they can start building a lead and then runs begin to equal time.

But every cricket innings hangs from a slender thread.

In scenes typical of the era, Hughes and Hogan are dismissed back-to-back and Hookes and Jones follow shortly afterwards.

Now the Aussies are seven wickets down and still 50 runs behind. My optimism – which is a naturally re-occurring substance within my boyish soul – is battling with my perception of reality. Surely defeat is now inevitable.

But my boyhood hero, Allan Border, is at the crease. After scoring 98 not out in the first innings, he’s in pleasing form. Australia can’t win, but the match can still be saved. If only we can hang on.

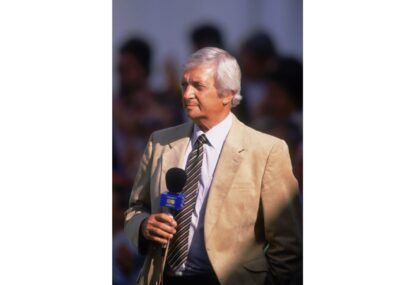

Allan Border in his XXXX jacket. (Photo: Archives New Zealand. – Flickr)

Border and Lawson put on 30 runs and Border and Hogg put on another 42. Now Australia enjoys a precious 25 run lead.

But sneaking out to the crease is Terry Alderman, one of the least accomplished and most poorly equipped ‘batsman’ in my cricketing life.

There’s still two hours of play remaining in the match. Take Alderman’s easy wicket, and the Windies will knock off the 25-run lead before you can say `Isaac Vivian Alexander Richards’.

Lying in my bed in Dural, listing to the ABC commentary on the radio, I’m wide awake and transfixed. Every ball carries with it all my hopes and dreams.

If Alderman gets out, all is lost. With every ball survived, I exhale with temporary relief and condensation starts gathering on my blue doona. I will my heroes to hang on.

Australia can’t possibly win this Test, but that doesn’t mean they are going to lose.

Ball after ball, over and over and ten-minute block after ten-minute block, Border and Alderman defy the West Indian bowlers. I’m counting every ball and every run. Slowly those runs start accumulating and slowly, ever so slowly, the lead builds.

Runs equal minutes, now, because every run scored translates to more time required by the Windies to chase them down.

By the time I am compelled to prepare for school, Border and Alderman have somehow constructed a lead exceeding 60 runs and there is no longer sufficient time for those runs to be scored – even if either batsman gets out.

Border scores his hundredth run in his epic innings and Viv Richards shakes his hand. The match is declared a draw.

Vivian Richards batting (Photo: S&G/PA Images via Getty Images)

On the way to school, I can’t stop telling my father and brothers about the drama. Though the match ended in a draw, it was akin to an Australian victory.

On the way home, that evening, I buy a copy of the evening paper which rightly compared Border and Alderman’s heroic exploits to those of Slasher Mackay and Lindsay Kline, who stubbornly defied the West Indian bowlers in Adelaide for two hours to draw the 4th Test during the famous 60/61 tour; probably the most famous drawn Test in cricket history.

Honour in a lost cause

Cricket is the only sport where your team can be thoroughly, completely and hopelessly outplayed for five days but not lose.

A draw is not the same as a tie.

A tie is possible in any number of sports – from soccer to rugby league to cricket itself – where the competing teams end the match on the same number of points.

To win a Test Match, however, (barring declarations) you have to take 20 opposition wickets whilst scoring more runs. You might accumulate three or four times as many runs as the opposing team; but unless you take that 20th crucial opposition wicket, the match is drawn.

The closest equivalent is a stalemate in chess.

A unique feature of Test Cricket is that your team might be thoroughly and comprehensively outplayed on the scoreboard, but not defeated.

There is honour to be found in that special brand of defiance. To find that deep resolve – even though the Test cannot be won – to maintain the fight to avoid losing.

The Test I have described in Port-of-Spain in 1984 is one of my favourite memories of listening to the Cricket on the radio. Even though the chances of Australia winning the Test were long gone, I held my frigid breath for every ball. And it meant so much to me that the Aussies battled hard and avoided defeat.

There are other examples.

Mike Whitney batting out the last over against a rampant Richard Hadlee – at the height of his extraordinary powers – to save a Test against the Kiwis in Melbourne in 1988.

Ricky Ponting resisting the Poms at Old Trafford in 2005, only to lose his wicket with an epic (and valuable) draw within his sights. Thankfully for Ponting, Glen McGrath saved the day.

And as recently as 2017, Peter Handscomb and Sean Marsh defying India in Ranchi to keep the series alive.

Not to give the impression that only the Australians have battled hard to secure a draw. Which Australian can forget the anguish of Mark Greatbatch’s long vigil in Perth in 1989 or Faf Du Plessis batting out the day in Adelaide in 2012?

South Africa’s Faf du Plessis. (AP Photo/Mark Baker)

Test Cricket is unique in that it offers the outplayed team the opportunity to launch a noble and defiant struggle to avoid defeat.

Most sports would count ‘defiance’ as a core value. But only Test Cricket truly rewards stubborn and heroic defiance in a lost cause.