The Roar's A-League Men tips and predictions: Round 26 - the jostle for finals positions is on in earnest

Here is the way the Roar expert panel sees all the action unfolding across the final weekend of play prior to the semi-finals.

Opinion

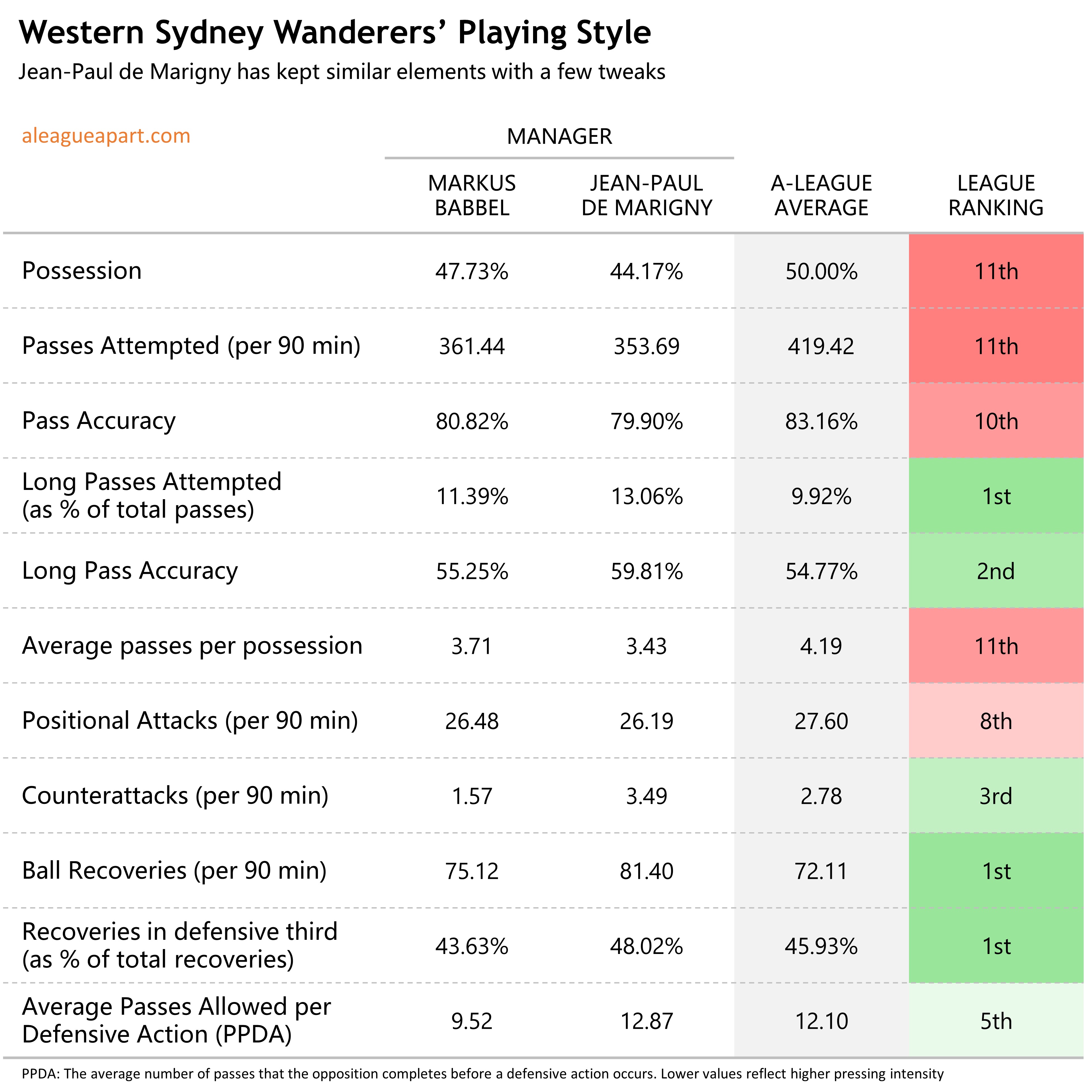

The Western Sydney Wanderers and Markus Babbel struggled in the 2019-20 season, and by the end of Round 15, Babbel was sacked, with his assistant Jean-Paul de Marigny taking charge.

Since then, their form has improved, with three wins, three draws and one loss. This article takes a closer look at the playing style of Western Sydney Wanderers under Jean-Paul de Marigny.

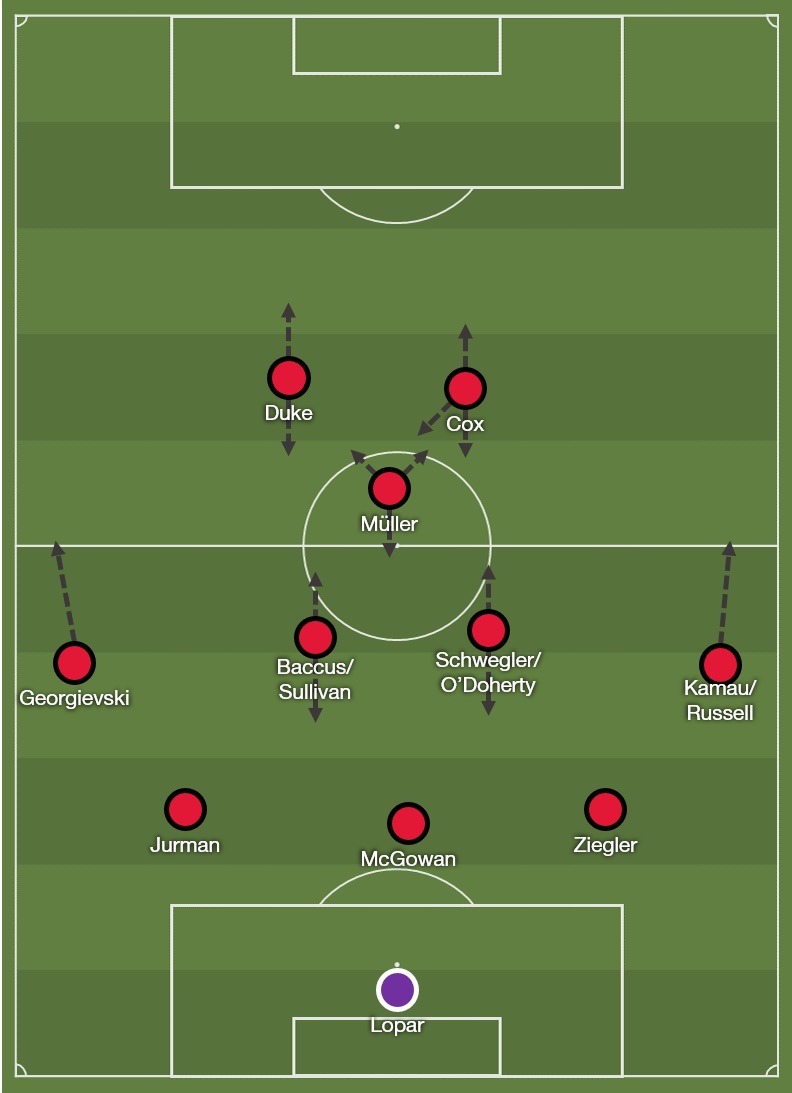

Western Sydney Wanderers’ formation and movements

New manager, same ideas?

The most obvious change that de Marigny has implemented is a switch in formation from a 4-2-3-1 to a defensive and counter-attacking 3-4-1-2. Where possible, he’s been quite consistent with his line-ups, with a few rotations (some which were forced) in midfield and with his wing backs.

That’s not to say that there’s been a huge change in playing style – actually, they’ve been pretty consistent with their previous ideas, and in some cases taken them further, while changing other aspects of their game. Under de Marigny, they’ve conceded more possession and relied on more on a passive defence, and slightly tweaked their short versus long passing mix. They’ve also increased the directness of their attacks and started using more counter attacks.

Because of their tendency to cede possession to their opponents (44 per cent average possession over the past seven matches), it makes sense to start with the Wanderers’ defence.

Defending from the front – blocking passing lanes

The three forwards don’t necessarily press high, but keep a tight block in the centre of the pitch, aiming to direct play wide rather than through the middle. The player who finds themselves in the attacking midfielder position will usually cover the deepest midfielder to make it difficult to progress the ball through the centre, while the two forwards will close down the centre backs – not necessarily to win the ball back directly, but rather to pressure them and force them to move the ball quicker and potentially causing errors.

In certain games, they may flip the first defensive shape to a 2-1, with only one player pressing the back line, and two slotting into the midfield. They did this against Sydney in Round 19, which made it difficult to find Sydney’s midfielders and attacking midfielders in the centre of the pitch.

Because the front three are fairly narrow, when the ball gets shifted over wide, the responsibility falls to the wing backs. The wing backs generally have a lower starting position, but will come forward as the ball is being shifted over to their side. They don’t press aggressively, but will close down quickly, and when the ball is played away from their flank, they will drop back into the defensive line.

Midfield zones – covering and tracking runners

The two central midfielders generally do not follow the press initiated by the forwards. They cover the zones in the middle of the pitch, tracking players as they enter these zones and protecting space in front of the back line. Here they close down opponents aggressively, and prevent players from receiving in space and turning on the ball.

They also track midfield runners into wider areas, helping their wing backs deal with wide overlaps. The midfielders are mobile, but Pirmin Schwegler prefers to play positionally or zonally, and can struggle with tracking runs from midfielders. When one midfielder is dragged wide, the other midfield will come over accordingly, covering the centre of the pitch. However, with only two players tasked with covering the whole midfield across the entire width of the pitch, the areas in front of the defensive line can be overloaded by their opponents, especially by dragging them wide, and then attacking the space created centrally.

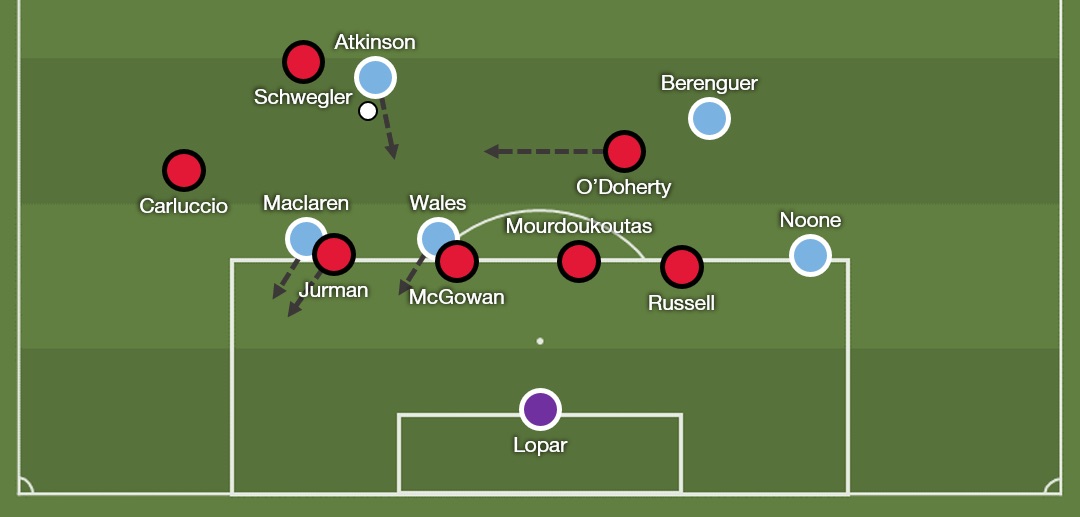

Adelaide’s movement works to disrupt the Western Sydney Wanderers’ defensive coverage, drawing out defenders, isolating a one-versus-one and attacking through the space created.

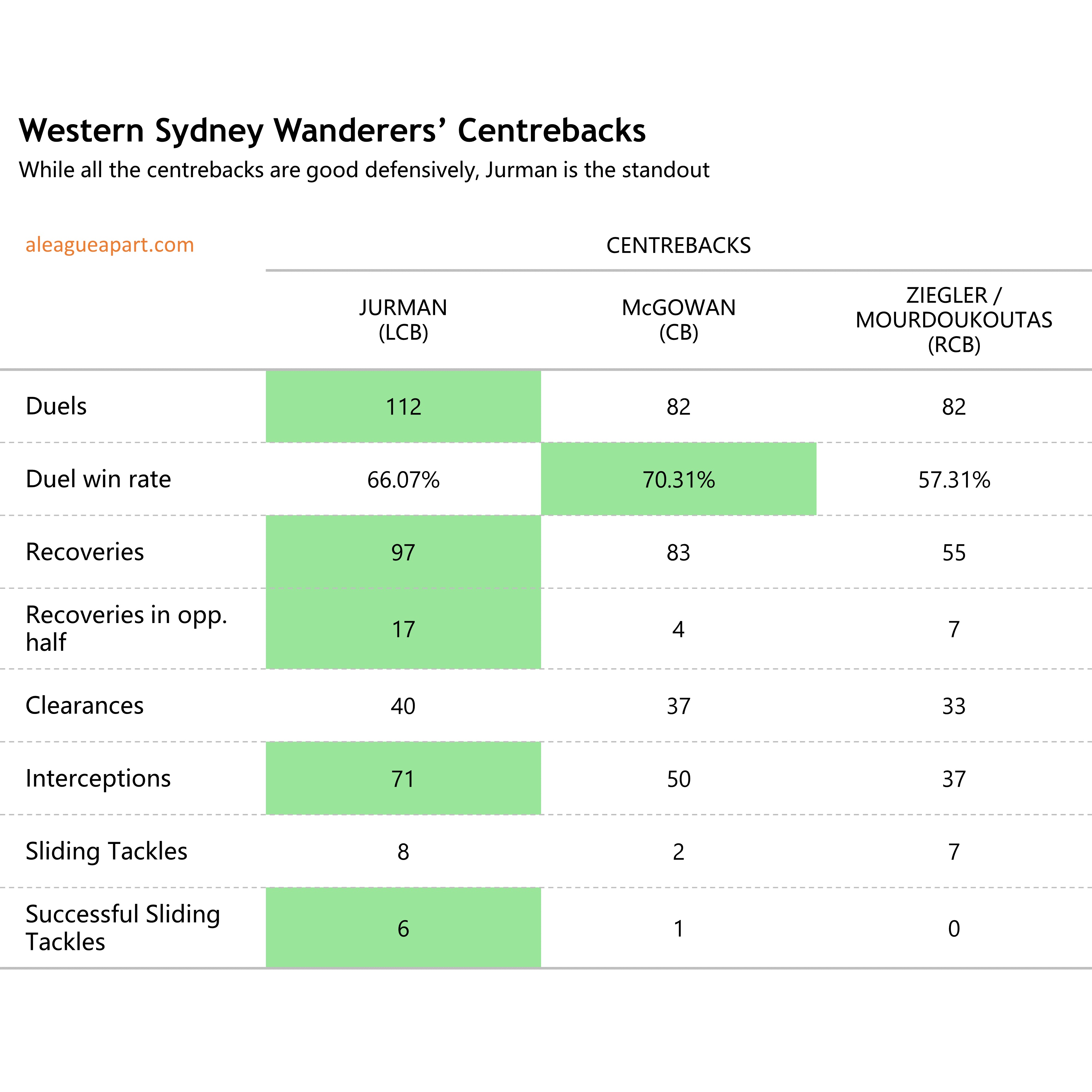

Centre backs closing down aggressively

With space able to be created in front of the defensive line, the centre backs are proactive and aggressive with their positioning. When the ball is played beyond the midfield, the centre backs are ready to jump out to challenge, either winning the ball, making it difficult for the player receiving the ball to turn, or closing down if the player manages to turn and drive. The outside centre backs also have a more active role in the defence, as they also have a role of covering runs into the channels, especially when the wing backs have pushed high up the pitch.

All three centre backs are good at pushing forward to defend, although Matt Jurman is the standout. He’s often the most aggressive with his positioning and his challenges, which reflects on the stats. Often he’s the furthest forward of the three centre backs, acting as a stopper in front of the other two, who shift over slightly in response to his positioning. Dylan McGowan mainly acts as a covering centre back, staying central and in the defensive line where possible, covering based on the defenders’ positions and sweeping up behind them.

The centre backs can be exploited by opponents by isolating them one on one. If the centre back who comes out of the defence is beaten, then the opposition is able to run directly into space or at the defensive line. Jurman with his aggressive positioning can be pulled out of the back line, leaving the other centre backs to have to deal with the direct threat.

Driving directly at the defensive line can also be dangerous, especially when a striker pins the centre backs by making a run, making it difficult for them to jump forward to close the player without opening up space for a run from the striker. This happened against Melbourne City, where Nathaniel Atkinson was able to shoot unopposed, which eventually resulted in a penalty being conceded.

Having beaten Schwegler, Atkinson can drive forward unopposed. Runs from his teammates pin the centre backs, while Jordan O’Doherty (marking Florin Berenguer on the other side) has to cover ground to reach him.

Towards the final stages of opposition attacks, the Wanderers’ structure is very compact with the three tall central defenders packing the box and the midfielders tracking opposing players’ runs into the box. Daniel Lopar is good in crossing situations, able to come off his line quickly to claim crosses.

In order to reduce the amount of space the opposition has on the edge of the box, it’s important that the forwards come back to support the defence, covering space both centrally (in front of the penalty area) and slightly wider (helping with wide overloads from fullbacks coming up). The forwards all generally have good defensive workrates and generally at least two will come back to help, but they can be slow to get back, especially after they’ve committed themselves forwards.

Defensive transitions

In defensive transitions, most of the time the Wanderers find themselves still in a decent shape, as they usually have their defensive midfielders in good spaces to counter press, as well as having three centre backs behind the ball. With the defensive line lacking in pace, they can still struggle against direct balls in behind or through direct dribbling. As such, one of the keys to their play in the defensive transition is the aggression again – either winning the ball to quickly stamp out any threat, or committing tactical fouls. Indeed, they have the highest number of fouls per 90 minutes in the league.

(AAP Image/Joel Carrett)

The wing backs generally find themselves high up the pitch on offence, and as a result, can be slow in returning back into defence, and again, the forwards can be slow to get back to help.

Attacking transition

Because of their tendency to be defending, and also because their forwards track back quite a lot, the attacking transition becomes a key for the Wanderers’ attacking game plan. Either through being instructed not to track back or just being slow to return to defence, often at least one forward is lurking slightly higher up the pitch and so upon winning the ball, the goal is to play the ball forwards quickly, with the other forwards and wing backs rushing up the pitch in support. The kind of ball that is played into the forward depends on who is the receiver – Mitch Duke is like a battering ram in the air while Simon Cox is also good in the air so an aerial ball can be played directly to them, while Nicolai Muller is better receiving the ball to feet.

Since the rest of the team is usually further back defending, the three forwards can often find themselves isolated from the rest of the team, and at times, it can look like two separate units – seven players defending and three players attacking. In order to keep possession from direct balls, the forwards must be able to find each other in support, and they generally have a good understanding with each other, combining well with interplay, receiving the ball, laying it off, and making supporting runs.

Attacking in possession

At goal kicks, the Wanderers have three options.

1. Play short to the centre backs. The centre backs will circulate the ball between them, hoping to create passing angles centrally or distributing to the wing backs. If the opposition sets up a high press, they will not play goal kicks short.

2. Medium length to the wing backs. If the opposition presses high, the wing backs will push up to midfield, often unmarked at goal kicks. Daniel Georgievski is better in the air, but Tate Russell can also challenge. If he is able to bring the ball down, he provides a quick and direct attacking option.

3. Long balls to the forwards. Duke is the main target here, but Cox is also good in the air. Aerial balls will be played slightly wider than central, allowing the wing backs, midfielders and other forwards to challenge for second balls.

The preference is to play the ball shorter. The three centre backs will look to play simple passes, finding the midfielders or forwards if the passing lanes are free in the centre, and if not, they will cycle the ball to the wing backs on the flanks. From here, the defensive coverage must shift over, and often the angles are left open for the wing backs to play the ball into the centre, or play one-twos to advance. If the midfielders are able to get on the ball in space, they can play good, penetrating passes direct, or cycle the ball out wide. They can also pop up on the flanks to help release the wing backs in behind through overloads and one-two combinations.

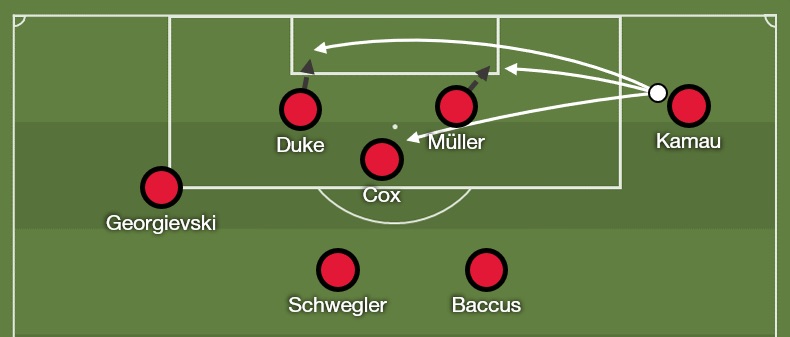

The aim is to find one of the forwards dropping into space in between the lines, with all three comfortable dropping in to receive. From here, the ball is either switched to the opposite flank, or the forwards will combine quickly to break through the defence. Muller is the most dangerous on the ball and when receiving the ball in space, dribbles directly from deep and plays penetrating passes through the defence.

While they can sometimes manage to work the ball forwards quickly to attack, their attacks will often make use of the wing backs. One of Duke’s signature moves is to receive the ball, take a touch backwards into space, before switching the play using a long ball out to the opposite flank into the wing back, and then turning to head into the box for the cross. The wing backs then drive into spaces on the flanks and look to cross the ball.

The Western Sydney Wanderers’ attack is heavily dependent on the wing backs, who are often involved in play via big switches of play. All clips are from one game against Sydney, aside from the last, which results in a goal against Melbourne City.

The Wanderers attack the box with the three forwards, with the wing backs supplementing from wide. While they attack with five players, it’s a different set-up to the Brisbane Roar’s, mainly due to the rapid and more direct nature of their attacks – they get forward from deep, rather than contributing to attacks from the front line. The wing backs will generally perch on the opposite edge of the box, ready for missed crosses or clearances. The midfielders are prepared around the edge of the box, ready for deflections or clearances, and also providing an option to circulate the ball to the opposite flank. With strong aerial options and targets in the box, partly due to the shift in formation to have three attackers, the Wanderers have options for crossing, and they make use of it. Their crossing accuracy is the highest in the A-League this season (37.89 per cent under de Marigny compared to 33.03 per cent being the A-League average).

A typical crossing situation is attacked with numbers.

Attack

1. Transition quickly to forwards who attack in a group of three

2. Combination play in the centre to retain possession or penetrate

3. Switch the play to allow wing backs to attack space wide

4. Attack the box with crosses

Defence

1. Protect the centre, block passing lanes and do not allow players to receive and turn with the ball in the middle

2. Aggression through closing down and defensive challenges

3. Defend deep with numbers – forwards come back to help

4. Pack the penalty area and dominate the box