If there has been one positive effect of the COVID-19 pandemic, it is the opportunity to press the reset button in nearly every area of life. In sport, in the economy, even in our everyday attitudes to the people around us.

For rugby, it has been something of a double whammy. The end of every four-year World Cup cycle usually heralds a review of the game’s governance and law-making processes, and that has been reinforced by the coronavirus pause. There has been more time to take stock of the direction in which the game is moving worldwide.

A widespread recognition already exists of need for the introduction of a global season, and a proper alignment between the playing schedules in the north and the south over a 12-month period.

The inhibiting factors are twofold: the professional clubs in England and France tend to work off their own agenda and want to eat space reserved for the international game, while the conservatism of the Six Nations committee blocks any attempt to move its crown jewel from the traditional February/March slot. With the Six Nations controlling 18 of the 26 votes needed to legislate change through World Rugby, the problem is obvious.

In contrast, on-field law changes are typically driven by the southern hemisphere, and particularly by New Zealand and Australia. With most of the money sitting with the English and French clubs up north, it becomes more important for the likes of the All Blacks and Wallabies to shape the international version of the game and sustain successful Test-match brands.

(Matt King/Getty Images)

The start of a new World Cup cycle is therefore often accompanied by a raft of law experiments – often for the general good of the sport, but always designed to bring it closer to the game New Zealand or Australia want to play.

The lifeblood of New Zealand rugby lies in its use of turnover ball and counter-attack, so it is no surprise that the latest batch of law changes in Super Rugby Aotearoa are designed to revive a game in which there are quicker rucks and more turnovers of possession.

Were the laws to advance from local experiment to global acceptance, it would undoubtedly take the further game away from teams featuring a ball-control attack (Ireland) or a high line-speed defence (South Africa) who proved to be the All Blacks’ toughest opponents during the last World Cup cycle.

The main areas of emphasis for the referee have become the policing of the breakdown and the offside line. The new rules require the ball-carrier to place the ball immediately after a tackle (no double moves or adjustments in body position), and support players to enter through the gate leaving their feet (no side entries or sealing off).

Defensively, contestants must be on their feet and directly on the ball at all times, while tacklers now have to roll out towards the sideline.

The experimental laws produced a glut of penalties in the two weekend matches between the Chiefs and Highlanders, and the Hurricanes and Blues:

|

Offside |

Attacking breakdown pens |

Defensive breakdown pens |

Other pens |

| Chiefs-Highlanders |

8 |

3 |

16 |

3 |

| Blues-Hurricanes |

6 |

15 |

8 |

4 |

| Total |

14 |

18 |

24 |

7 |

That’s 63 penalties over two games at a colossal average of 31.5 per game, two-thirds of which occurred at the breakdown. Only 11 per cent of the penalties occurred in situations outside defensive offside and the ruck.

Moreover, there was very little consistency in the refereeing of the ruck between the two games, with Paul Williams hammering the attacking side with a 5:1 penalty ratio, and Mike Fraser reversing the trend by pinging the defensive side twice as often as the attack.

If the aim was to create more turnovers at the tackle, then it was most certainly accomplished in the first game of the weekend in Dunedin:

|

| Rucks built |

Rucks lost to turnover/penalty |

Retention rate |

| Highlanders |

67 |

13 |

80.5% |

| Chiefs |

80 |

10 |

88.9% |

| Total |

147 |

23 |

84.3% |

To put those stats in some kind of perspective, Ireland averaged 118 rucks per game in their four outings against New Zealand over the last World Cup cycle, at a 96.8 per cent retention rate. To watch that rate drop to 84 per cent would be unmanageable for the coach of a ball-control attack.

Now let’s take a look at what this means in practice. The range of movement allowed to the ball-carrier before he places the ball is vital to the continuity of attacking play as the laws stand.

England’s opening attack against the All Blacks in the World Cup semi-final lasted for one minute, and contained six rucks and 15 passes. The phase prior to the key break down the right looked like this:

England number 6 Tom Curry takes the ball up to the line, and when he feels pressure coming from Ardie Savea above the ball, he inserts an extra roll to offset the New Zealand flanker and move the point of attack across the advantage line:

Now Sam Whitelock, Kieran Read and Joe Moody all have to retire behind the new offside line and space for Elliott Daly and Anthony Watson opens up on the following phase.

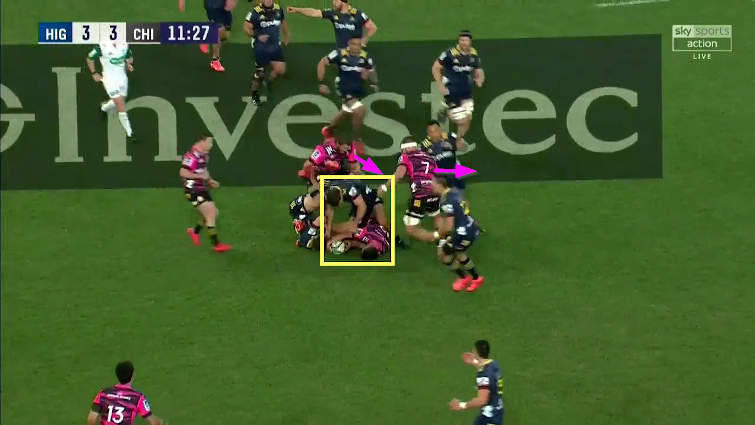

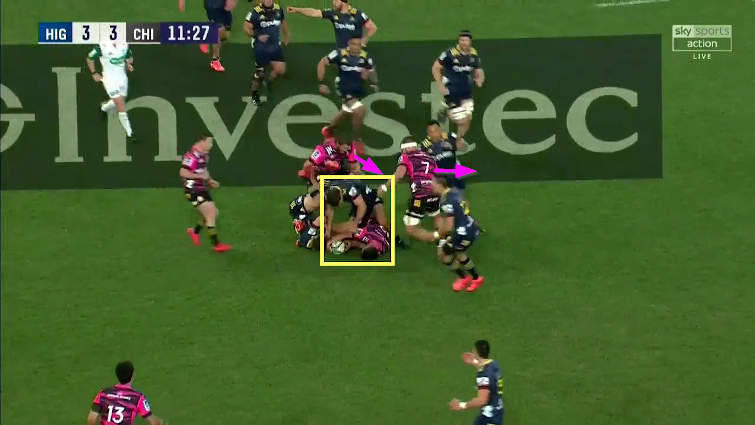

Let’s compare that with a similar instance from the Chiefs-Highlanders game:

Chiefs centre Anton Lienert-Brown rides over the top and falls forward in the first tackle, but because he has to place the ball immediately, it allows Highlanders number 7 Dillon Hunt in on the ball.

The support lines of both of the two main cleanout players indicate they are clearly expecting Lienert-Brown to make the extra ‘Curry roll’:

Does it not seem counter-intuitive for the defender to be rewarded in a scenario where the attacker has won the collision?

Whenever the ball-carrier did attempt to make a double move on the ground, he was ruthlessly punished by Paul Williams:

These are promising situations for the attack deep within the opposition 22, but both are lost to turnover penalties even though no defensive hands are visible on the ball after the tackle is made.

One of the central issues which emerged in the course of the Dunedin encounter was the lack of time afforded to the cleanout.

This should be a routine ruck win for the Highlanders, with two support players close to hand and facing a single defender. However the cleanout is given a window of just over two seconds in which to remove him before the whistle blows for another penalty.

In these circumstances, even defenders like diminutive Chiefs fullback Damian McKenzie can look like a world-beater at the tackle area!

McKenzie is knocked down swiftly by the cleanout – he is off his feet within one and a half seconds – but is still judged to have stayed above the ball for long enough to justify the turnover penalty. Another counter-intuitive outcome.

When similar scenarios occurred in the Blues-Hurricanes match, the boot was on the other foot and the refereeing interpretations were completely different:

All three sequences occurred in just the first ten minutes of the match. In all three examples, it impossible to know what the defenders could have done differently, either to win turnover or avoid a penalty against them.

In the first instance, Blues number 7 Blake Gibson survives above the ball for at least two seconds and there is no evidence of immediate release by ball-carrier Ngani Laumape, but Gibson does not receive the reward he surely would have from Paul Williams.

The second scenario is one where the tackler, Blues number 12 TJ Faiane, is required to roll out of the tackle area towards the sideline. He appears to be doing everything within his power to achieve it, despite being pinned down by TJ Perenara. The penalty goes to the TJ in yellow though, not the one in blue!

In the third example, James Parsons competes on-ball and shows a clear release as soon as he leaves his feet, but he hears the shrill blast of Fraser’s whistle anyway.

Summary

Thirty and more penalties per game is not the product that the experimental rules were aiming to showcase. The penalty counts dominated both games and forefronted the referee in a very un-Kiwi like manner.

The fact that 67 per cent of the penalties occurred at the ruck is also a matter of concern, and so is the lack of consistency between the two officials. Where Paul Williams refereed the attacking side out of the game, Mike Fraser had his patch very much over the other eye.

The new rules demand extreme accuracy from all of the ball-carriers, tacklers and support players involved at the breakdown on either side. They have to be very precise in their timing of release, angles of entry, and body positions over the ball, and they have to make their decisions and perform their actions within a narrow two-second window.

(Joe Allison/Photosport via AP)

It is just the first weekend of Super Rugby Aotearoa, and things will improve. But right now, it would be an impossible task to convince either coaches or referees in the northern hemisphere of the need for change in the laws, especially at ruck time.

There is far more likelihood of an agreement between the hemispheres on a global season structure, especially if a new home-and-away version of the Six Nations comes to pass at the end of the year. If you can do it once, you are more likely to do it again. That would be the most important change of all.