‘Tis the season, it seems, for naming all-time greatest themed cricket teams, which makes it a perfect time to finally settle the question of what is best: a beanpole or a bean sprout?

Put another way: if you pitted the greatest tall cricketers against the greatest short ones, who comes out on top? This week we begin the process of finding out by naming the definitive all-time greatest tall cricketers XI.

Now, first, some notes on selection. This is a team of the greatest tall cricketers, not simply a team of the tallest cricketers. Some particularly elongated players miss out because, although they tower over all physically, their performances were far more diminutive. You have to be unusually tall to get into this team, but you also have to be good. There’s a balance to be achieved here though: a tall champion might give way to a slightly less accomplished player, if the latter outdoes him in terms of looking like a bit of a freak.

Now, as to the definition of tall, it is of course all relative. Two-metre fast bowlers litter the annals of history, whereas skyscraping top-order batsmen are much less common, and lanky wicketkeepers even rarer. So the threshold for entry is a little lower for the top seven compared to the bottom four, and where there are no real giants to fill a position, a man of simply above-average height may have to be drafted in.

As to the definition of tall itself, there is no strict mathematical formula being used here: the only requirement is that a member of this team must be tall enough so that when a reasonable person looks at him, they may well say, “Goodness that’s a tall fellow” or words to that effect.

All that said, here is your beanpole XI – a team of frightening bowling strike power, and some aggressive if not entirely reliable batsmanship.

1. Ravi Shastri

At 1.91 metres, Shastri is not quite a colossus, but he’s well above the mean, especially when it comes to the opening position, which is traditionally the province of those able to duck under bouncers with ease. His long career with India saw him notch many vital innings – most memorable to Australians will be his 206 in Sydney when he used his long reach to good effect to grind chubby debutant Shane Warne into the dust. A genuine all-rounder, his more-than-useful left-arm tweakers will also add value to the side.

2. Peter Fulton

Difficult to go past a man whose nickname was “Two-Metre Peter”, even if it was slightly inaccurate: Fulton actually clocks in at just 1.98 metres. The cloud-butting Kiwi’s career did not quite fulfil its potential, but at his best – as in his twin hundreds against England in Auckland – he was a batsman of considerable skill, able to play with calm patience or attacking flair as the situation demanded.

3. George Bonnor

Representing the early days of Test cricket, George Bonnor’s statistics are less than impressive – 512 Test runs at just 17. However, one does need to take into account that he played in the 1880s, an era of dreadful pitches and smaller balls, when bowlers ruled the roost to average 25 was near-miraculous. It was also an era when humans in general were smaller than they are now, so Bonnor’s 1.98-metre frame would’ve made him a mighty intimidating sight – especially on occasions such as the fourth Test of the 1885 Ashes, when Bonnor pulverised the English attack to the tune of 128 in under two hours. The bearded titan crashed 14 fours and three sixes, back when to hit a six meant not just clearing the fence, but hitting the ball out of the ground entirely.

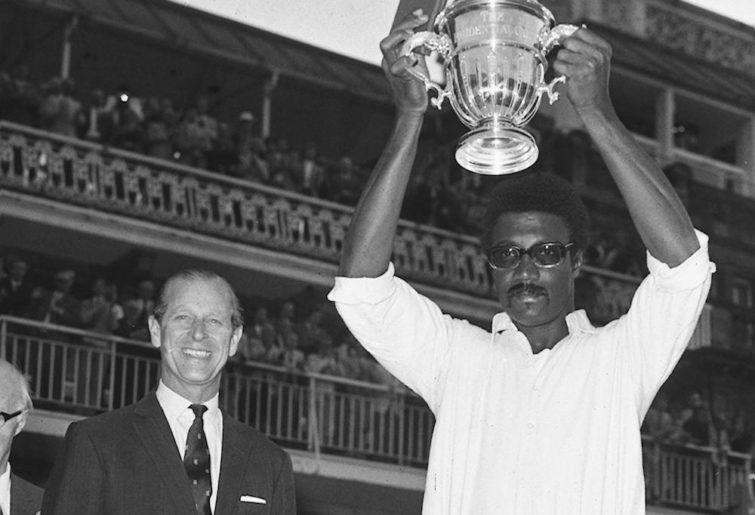

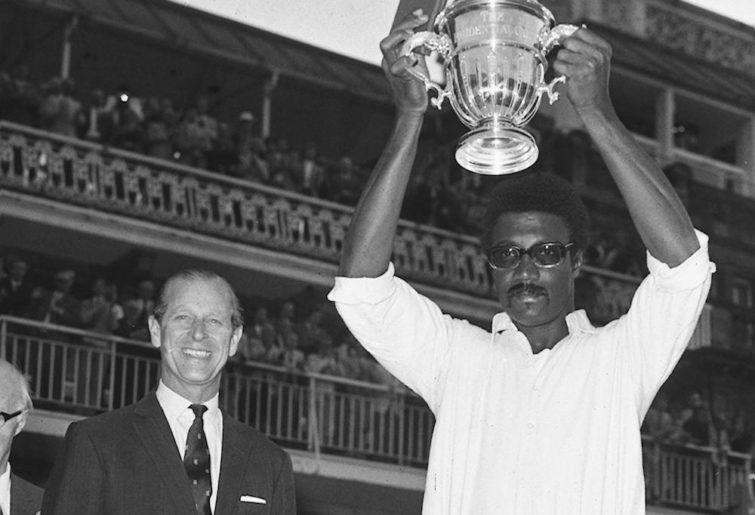

4. Clive Lloyd

In this company, Lloyd’s 1.93 metres wouldn’t make him stand out as much as he did for the best part of two decades in a succession of champion West Indian teams. The latter half of his career saw him captaining the side in a stint that, from 1980 to 1985, resembled nothing so much as Genghis Khan’s sweep across central Asia. A ruthless leader, Lloyd was also a batsman of thunderous brutality who could put opposing bowlers in as much physical danger as opposing batsmen were from his battery of pacemen. His tornado of a knock in the 1975 World Cup final marked the first burgeoning of a superpower, and a generation of batsmen from Gordon Greenidge to Viv Richards to Richie Richardson followed his lead.

(Photo by PA Images via Getty Images)

5. Tony Greig

The man unfairly neglected when talk turns to England’s greatest all-rounders, who came from South Africa during that country’s isolation to seek opportunity in Blighty, and ended up captaining them. Greig was good enough to average 40 with the bat and 32 with the ball, figures that compare quite favourably with the likes of Ian Botham and Andrew Flintoff, and if he lacked those men’s explosiveness in either discipline, he more than made for it with skill, courage, dependability, and an unquenchable competitive drive. He cut an extraordinary figure on the field, particularly when batting with tiny ally Alan Knott, and his 1.98 metres were not always an asset when Jeff Thomson speared it at his sandshoes. But nobody who played against him was ever in doubt that they were in a contest.

6. Tom Moody

Had Long Tom risen just five years earlier – or 15 years later – he’d have surely been a permanent fixture in Australia’s Test side. As it was, the glut of batting skill in the early 90s combined with selectorial sabotage – Moody was forced into the unsuitable role of opener on the 1992 tour of Sri Lanka to depressing effect – to unjustly abbreviate his Test career. He still managed a couple of Test hundreds, though, and his one-day career was far more fruitful: a member of World Cup-winning squads in 1987 and 1999, his frugal medium pace and ability to hit a ball quite unfeasible distances stood him in good stead. Coming in at just one centimetre under two metres, he was the epitome of “long levers”.

7. Adam Gilchrist

At just 1.86 metres, Gilchrist might as well be a member of the Lollipop Guild when placed in this team. But the fact is that wicketkeepers tend to be built close to the ground, so as to make a life spent crouching that much more comfortable. No truly huge wicketkeepers have succeeded at the highest level, and the only realistic competitor for Gilchrist’s place was Clyde Walcott, who had a couple of centimetres on Gilly but gave up the gloves early in his career to focus on his batting. Gilchrist, therefore, though only fairly tall for a human being, is a positive giraffe in keeping ranks, and kudos to his back and knees for holding out so long. His stunningly ferocious batting, of course, fits right into this side.

(Photo by Hamish Blair/Getty Images)

8. Jason Holder

With the plethora of lofty quicks available, it would be unseemly to allow anyone under two metres into the fold here, and the current West Indian skipper qualifies handsomely. Holder is a great leader of men, as evidenced by his efforts in bringing the Windies back to competitiveness in the Test arena. He’s also a fairly handy cricketer himself, as evidenced by his six wickets in the first innings of the recent victory over England, not to mention a safe pair of hands in the slips and batting chops good enough to boast a Test double hundred.

9. Joel Garner

They didn’t call him Big Bird because he was yellow and friendly. In fact, apart from height there are few similarities between the beloved resident of Sesame Street and the human siege engine who terrorised hapless batsmen by the dozens in the 1980s. Standing 2.03 metres and making sightscreens the world over seem inadequate for the task, Garner specialised in balls that alternately reared at your throat and speared at your toes. His yorker was a nightmare to negotiate, and though not as rapid as his great compadres Malcolm Marshall and Michael Holding, he was just as likely to inflict damage: the Australian touring party of 1984-85 can testify to Garner’s willingness to bruise and batter.

(Mark Leech/Getty Images)

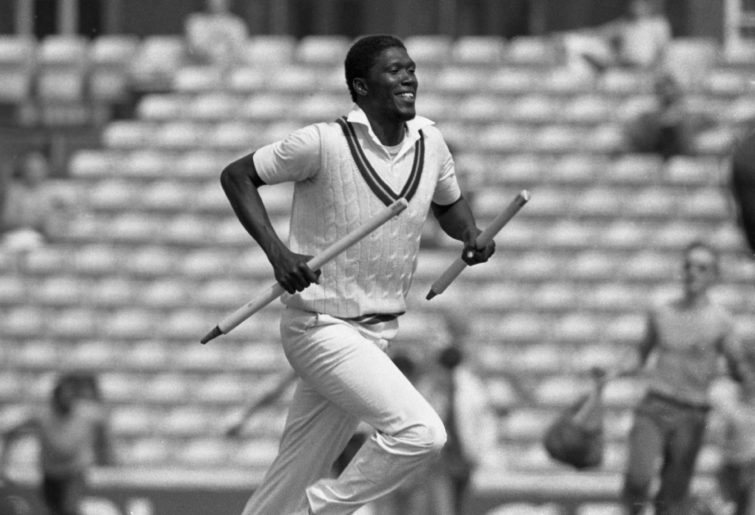

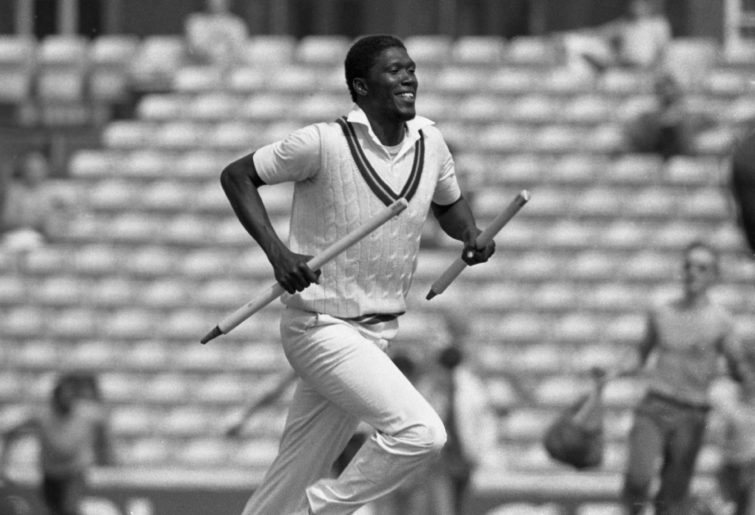

10. Curtly Ambrose

Much like Garner, only meaner. And better. Ambrose’s graceful lope to the wicket and loose-limbed delivery belied the fiendish precision of his bowling: outside Glenn McGrath, there can never have been a fast bowler less likely to give a batsman loose balls to put away. Ball after ball pounding in short of a length, cutting in at the gloves, jagging away to the slips, making the poor bugger at the other end play time and again, and every one followed up by the most ominous glare in cricket history. Occasionally Curtly would mix it up, and a ball would spit at the face or arrow in at the stumps. Myriad teams throughout the ’90s found themselves on the receiving end of an Ambrose special, when the Antiguan giant would raze a batting line-up to the ground in the twinkling of an eye. Steve Waugh made his reputation on withstanding Ambrose’s assault, because everyone in the cricket world knew just what a fearful assignment that was. Two point one metres of relentless menace, it’s remarkable what a lovely chap he is when you get to know him.

11. Bruce Reid

The image that will come to mind for many when they think “lanky fast bowler”. Also the image that will come to mind for many when they think “hilariously inept batsman”. As tall as Joel Garner, but about one third the weight – hence the nickname “Chook” to contrast with Garner’s “Big Bird” – Reid took 113 Test wickets at 24.63. These are highly creditable figures, but they could’ve been much better. Indeed, Reid could’ve – should’ve – been one of the greatest bowlers in Australia’s history, were it not for a body with all the resilience of a water cracker. In successive MCG Tests in 1990-91 and 1991-92, the sentient stringbean took 25 wickets against India and England, but he broke down more easily than Britney Spears’ marriages, and in the end chronic back injuries robbed Australia of a champion. When he could make it onto the field, though, the languid left-armer could be utterly lethal, the bounce generated from his elevated delivery combining with an enviable ability to swing it both ways. On song, he was near-unplayable, making top-class batsmen look as clueless as he always did with a bat in his hand. The fact his career encompassed just 27 Tests in seven years is a crying shame.

Next week: the All-Time Greatest Short XI.