A common, reoccurring fascination with Don Bradman is how much he would or wouldn’t have averaged were he playing today.

Given that this question has come up frequently over the near 40 years I have been following the international game, it is now not so much a question of were he playing today but rather had he played in any subsequent era post his own.

For example, his average had he played in the 1960s, while likely different to his actual average in his actual era, may well also be different to what his average might have been had he played in the 1970s and ’80s or after the turn of the 21st century.

An idea for a new angle dawned on me. Rather than merely regurgitate the familiar and pertinent premises about stronger bowling attacks and pitches less conducive for productive batting, a light bulb suddenly went off in my head along the lines of the average length of time Bradman actually spent at the crease and the different amount of balls he would have faced had he played in different eras of different every day over rates?

It was in the Bradman albums, which I acquired nearly 30 years ago, where I read that he scored at an average rate of 50 runs per hour in all first-class cricket, which spanned 338 innings, 28,067 runs at an average of 95.14 with 117 centuries.

His Test component consisted of 80 innings, 6996 runs at an average of 99.94 with 29 centuries. Based on over rates of the day – approximately 120 balls bowled per hour – studies have been done to accurately estimate his strike rate at around 70 runs per 100 balls faced in all first-class cricket, and around 61-62 in Test cricket.

Based on these things, if Bradman scored at 50 runs per hour in all first-class cricket, and averaged 95.14, then this means that the average length of a Bradman first-class innings was about 115 minutes. During this time, based on 120 balls bowled per hour – whether 20 six-ball overs in England or 15 eight-ball overs in Australia – then 230 balls would be bowled, of which Bradman would face approximately 136 of them.

This amounts to 59 per cent of the strike. I am going to make the assumption that he commanded the same percentage of strike, on average, over the course of his Test innings.

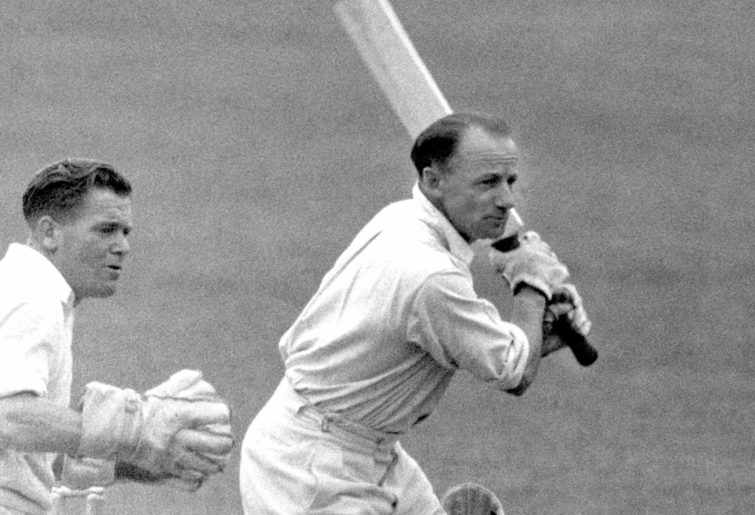

(PA Images via Getty Images)

Striking at somewhere between 61 and 62 runs per 100 balls faced in Test cricket with his 99.94 average sees him facing around 162 balls per Test innings. That’s about 275 balls bowled by the opposition on average over the course of a Bradman Test innings.

With over rates remaining the same, then this means that Bradman on average spent 2.29 hours at the crease per Test innings, which amounts to 137 minutes and 30 seconds. Now, I am going to assume that this level of concentration would remain the same no matter what era he would have played in, in anyone’s alternative fantasy. I am basing this assumption on two things.

1. The ferocious West Indian pace attacks from the late 1970s until the early to mid-1990s were not only grounded in unrelenting pace, but also in slowing the game down by bowling considerably fewer overs per hour. This method had particular benefits on the rare days when conditions for batting were so good that even these ferocious attacks found wickets hard to come by.

For example, on a flat pitch, if the opposition managed to score three runs per over – a very good rate in the 1980s – and pass 200 with only three wickets down by bowling only 12 overs an hour rather than the expected 15, then come stumps on Day 1, their opposition would only have reached 3-216, rather than 3-270.

This tactic put an opposition batting line-up behind the clock and made a day of potential rare domination against these attacks a grind. Then, the bowlers could come out fresh the next day and bundle them out for under 300, rather than see them push on beyond 400, and this was a form of mental disintegration.

I don’t want to get too long winded, but my point is that there is only so long, time wise, that a human being can maintain concentration levels, and Bradman would not have been an exception to this.

2. Anyone unconvinced by the previous part, allow me to perform a comparison between Bradman and Viv Richards. The Master Blaster averaged 50 in Test cricket at a strike rate of 67, which means he faced on average only 75 balls per innings (compared with Bradman’s aforementioned 162).

If we apply the 59 per cent of the strike as a standard average for all legitimate stroke players, this sees only 127 balls bowled by the opposition during an average Richards innings. King Viv played in an era where 90 overs a day was the expected norm, and only his own team really took the mickey out of this in the manner described in the previous part.

The teams the West Indies faced at least had regular spinners, so deliberately slowing the game down was somewhat more difficult. If we conservatively estimate that the Windies’ opposition teams averaged 14 overs per hour during the 1970s and 80s, then this means that an average Richards innings spanned approximately 90 minutes and 40 seconds – almost 48 minutes (or more than 50 per cent) less than Bradman’s average innings time wise.

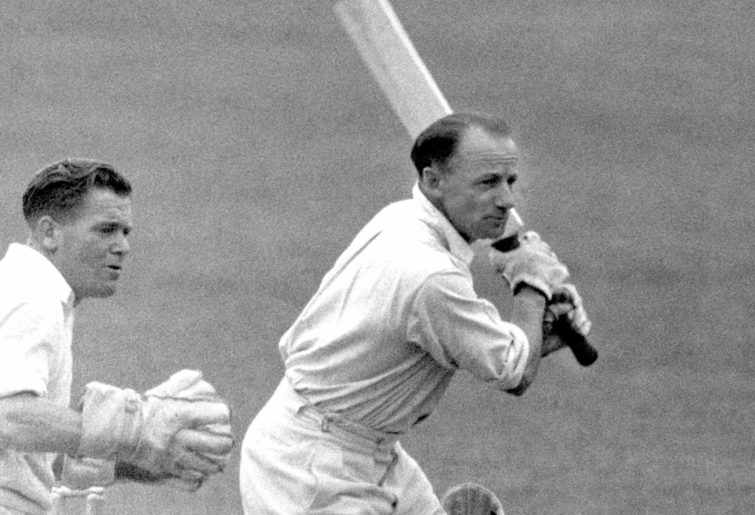

(S&G/PA Images via Getty Images)

This last sentence is less a reflection of over rates across different eras, but more the concentration powers, time wise, of different batsmen. My mathematical premises still leave plenty of room for Bradman to sharpen his skills by hitting a golf ball against a circular tank for hours and hours on end in order to achieve superiority over all other batsmen.

Now to cut to the chase. If Bradman had played in the 1970s and ’80s, then over rates of the time might give him a base average in Test cricket of around 70 or 71. Bear in mind, only three batsman averaged more than 50 during the 1970s and they were Viv Richards, Greg Chappell and Sunil Gavaskar.

What may well take Bradman’s average slightly down on this estimate is the higher number of world-class bowlers across a bigger variety of opponents compared to his own era, as well as some somewhat more bowler-friendly pitches served up during this particular era.

Also, I wonder given his health problems in the mid-1930s how Bradman would have handled tours to India and Pakistan at a time when practically no Australian players wanted to go to those countries?

Playing from say the early or mid 1980s to the end of the 1990s would have seen the same constant with a high percentage of world-class bowlers in the opposition teams, although pitches were on the improve, slowly but surely, and administrators were gradually getting stricter with over rates.

However, the strictness came not with magically ensuring that teams bowled their mandatory 90 overs in six hours, but rather were made to stay out there beyond the six hours until they had done so. Therefore, Bradman’s average innings time wise stays at around 137 minutes.

However, during the 1990s, conditions greatly improved in terms of player comfort when touring the arduous sub-continent. I’ll stick with the base 70-ish average and assume less of a drop taking into account the various factors outlined.

In either case, he would have faced off in a sizeable percentage of his Tests against those aforementioned ferocious West Indian attacks, who also tended to stretch gamesmanship to its absolute limits through diabolically slow over rates before administrators wised up.

Fast forward to the most recent decade up to the present time and we have seen a shift from 90-over days that stretch beyond seven hours to a maximum of six and a half. However, over rates today put even those four-pronged West Indian attacks in the shade.

A standard day of Test cricket these days sees about 80 overs bowled in the standard scheduled six hours of play, and perhaps a further six in the maximum extra half hour. This equates to barely 13 overs per hour, so based on Bradman’s average length of stay at the crease, time wise, through no fault of his own, I can’t see Bradman averaging more than about 66 or 67.

This does not mean that I consider Steve Smith to be as good a batsman as Bradman, or even the second best after him in Test history because my estimate for Bradman’s average playing today is a finishing career average, whereas Smith’s (average) will almost certainly start to decline within another year or two at the latest.

By the same token, there is no reason whatsoever, given normal career trends for great batsmen, why Smith’s average should not still be well and truly above 50 at career’s end. I do not necessarily consider Smith to be a superior batsman to Ricky Ponting or Greg Chappell, but only a fool would deny he is certainly just as good.

(Mike Egerton/PA Images via Getty Images)

Back tracking to the 1950s and ’60s, these two decades would see Bradman averaging closer to his near 100 average than any subsequent decade or era simply because of standards. There were minnows aplenty who were still a long way off being genuine forces, such as India, Pakistan and New Zealand.

There were also less world-class bowlers per team even among the genuine powers, such as England and by now the West Indies, although there were certainly some genuine world-class bowlers about, such as Fred Trueman and Wes Hall.

I don’t know what over rates were like in the 1950s and 60s but I would assume they were not quite as good as in the 1930s, but more than likely still better than the 1970s and beyond. This would perhaps see Bradman averaging somewhere in the vicinity of 80-85 in Test cricket, if I take a wild guess that maybe the equivalent of 100 six-ball overs were regularly bowled in a strictly adhered-to six-hour day of playing time?

But what about one-day cricket? I am going to imagine that Bradman would have struck at around 80 runs per 100 balls faced playing between the end of World Series Cricket and the turn of the new century, and possibly as high as 99.94 runs per 100 balls faced playing today.

In the period 1979-2000, 80 was an exceptionally high strike rate in one-day cricket, which very few players achieved, whereas today, I am certain Bradman would be every bit as expert as AB de Villiers in adapting his game to take in the 360 degrees offered by the playing area in order to manipulate the field.

In the contemporary era, compared to the 1980s and ’90s, playing conditions in one-day cricket are also far more lopsided in favour of batsmen, not least of which is the consistently flatter and truer pitches.

It gets back to the powers of concentration. Making the same assumption that Bradman’s would last for, on average, 137 and a half minutes per innings, which equates to 65.5 per cent of a team’s available 50 overs in the format where over rates have always been far more strictly controlled by administrators.

This amounts to 32.4 overs, or 196 deliveries, of which based on the earlier notion of 59 per cent of the strike, Bradman would face 116 of them. I suppose there is also room for argument that strike might well be more evenly shared between batsmen at the crease in one-day cricket, though I have no reliable statistical analysis to either support or disprove such an assertion.

For the sake of argument, let’s imagine that Bradman, in theory, gets to face on average 100 balls per one-day innings.

(Photo by S&G/PA Images via Getty Images)

There is, however, one other very important definite variable in one-day cricket to consider and that is the compulsory closure after 50 overs. The thing is this: Bradman played in an era where all first-class games in Australia for the large majority of his career were timeless.

Even today, with five-day Tests, a batsman only has a one in four chance of going into bat with less time remaining than their average powers of concentration – in Bradman’s case 137 and a half minutes – remaining before time is called.

In one-day cricket, in principle, Bradman would have to be in no later than 17.2 overs into Australia’s innings to be afforded the opportunity to bat for his average time at the crease, irrespective of whether Australia is batting first or second.

There would be times he would be in well within this time frame, for sure, but in eras providing good opening combinations there would also be days when he would not be required to appear in the middle until well after the 30th over in the wake of an outstanding opening partnership of 150-plus.

Let’s imagine the first wicket fell at 33.2 overs, leaving precisely 100 balls remaining of which Bradman would face on average 59 of them, or perhaps only 50 (of the remaining deliveries in Australia’s innings). What would he do with those 50-odd deliveries he got to face?

Would he just plod along for an unbeaten run-a-ball half century while big hitters exploded all around him – with the Don perhaps feeding them the strike – or would he lift the tempo himself and perish for 70-odd in the 49th over?

It’s a tough one, and not easily reconciled. However, with my estimated 1980s and 1990s strike rate of 80 in one-day cricket he would also have a maximum average of around 80, whereas his near run-a-ball strike rate in this more recent time might see him average a maximum of around 99.94.

Whether either would be realistic in the abbreviated form of the game in is certainly debatable, given the overall nature of one-day cricket as a whole, and his average in either or both eras may well end up at least slightly downsized if for no other reason than the aforementioned variable unique to limited-overs cricket.

However, I none the less feel certain that Bradman would have been an absolute pyjama Picasso.