How do you measure an Australian opening pair’s success, and which pair would then claim first place? This article attempts to answer both questions.

A stable pair assists its side to win matches and series. Between 1985 and 2015 the team benefitted from a series of successful combinations. Subsequent instability has put the spotlight firmly on the batsmen that have followed Chris Rogers and partnered David Warner. During the past five years alone, Australia has tried 15 different combinations.

Eighteen months ago in a drawn Ashes series Warner, Cameron Bancroft and Marcus Harris averaged 8.50 runs per partnership with a highest stand of 18. This summer in a Border-Gavaskar Trophy series loss, five different opening batsmen added more than 16 runs only twice in eight attempts. When Will Pukovski became Australia’s 460th Test cricketer he also became its 167th opening batsman, and he and Warner formed its 246th different first-wicket combination.

(Photo by Cameron Spencer – CA/Cricket Australia via Getty Images)

The game’s evolution makes comparisons challenging. Matches before the 1890s were generally low-scoring. Australia’s 104 innings before 1899 yielded just one opening stand worth 100 runs. Spin bowlers often took the new ball, with great success.

Until WWII batting orders varied according to match conditions. The existence of only three then four state teams meant that a small pool of batsmen moved up and down the order, rather than into and out of the side. While Matthew Hayden and Justin Langer batted together 113 times, Australia used 46 different combinations for its first 112 innings, and more than half of those pairings were for a single innings.

After WWII, specialists became the norm. Pitches and bowlers’ approaches were covered. New-ball attacks almost always comprised fast, swing and seam bowlers. The numbers of matches and opponents increased. The Sheffield Shield’s expansion created more competition for positions. Batsmen such as Arthur Morris and Colin McDonald either opened, or did not play.

Historically, opening batsmen have been steady rather than aggressive. Herbert Sutcliffe, Len Hutton and Geoff Boycott honoured the Yorkshire mantra of ‘no boundaries before lunch’ with scoring rates below 40 runs per 100 balls. Australians such as Alec Bannerman, Herbie Collins, Bill Woodfull and Jimmy Burke batted similarly.

Such tactics were understandable in eras of timeless Tests, high over rates and uncovered pitches. Openers’ highest priorities were to see off the new ball, tire out the faster bowlers, and wait for the pitch to lose any early life. Boycott always added two wickets to his team’s score when assessing whether it was on top.

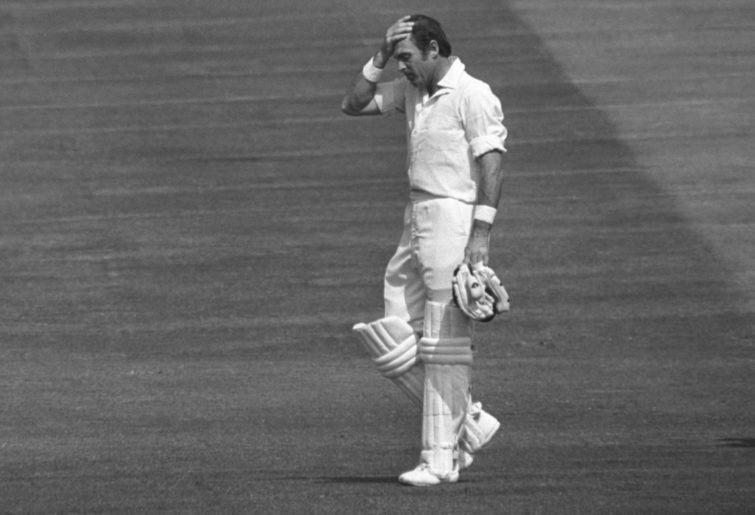

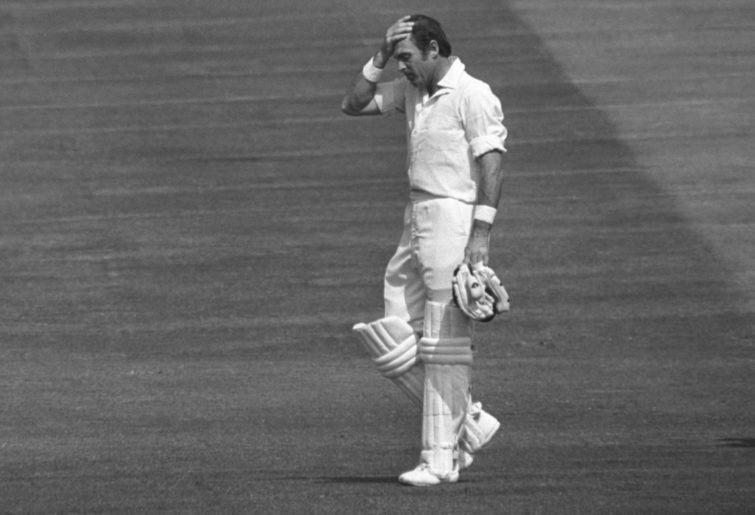

(S&G/PA Images via Getty Images)

Attacking openers have since become more common with contributing factors including covered pitches, one-day formats, power bats, shortened boundaries, protective equipment and chief executives’ pitches made to last.

Hayden, Warner, Virender Sehwag, Chris Gayle and Sanath Jayasuriya are among the fastest-scoring batsmen of all time, each exceeding 60 runs per 100 balls. Victor Trumper is the only earlier opening batsman with a similar scoring rate.

However their ability to quickly put a team in a dominant position has always been offset by the risk that early dismissal exposes a middle order. One in a side is ideal but two are unusual. Trumper and Reg Duff, and Hayden and Langer, are rare examples of successful pairings in which each partner had a career scoring rate in excess of 50 runs per 100 balls.

The most effective duos have instead tended to comprise a steady scorer and a more rapid one. Sutcliffe had Jack Hobbs, and Desmond Haynes had Gordon Greenidge.

Woodfull’s average innings of 46 runs lasted 135 deliveries, enabling long partnerships with faster-scoring teammates such as Don Bradman and Stan McCabe.

In contrast, Warner’s average one lasts only 72 deliveries and he often dominates a briefer partnership then exposes incoming batsmen to a newer ball, fresher bowlers and more responsive pitch.

(Photo by Cameron Spencer/Getty Images)

So how do we compare opening pairs from different eras and of different styles ? I suggest these criteria.

a. Average runs per partnership

A straightforward measure, but one big stand can skew the figure. For example a stand of 250 and four zeros means four failures in five innings, but still yields an average partnership of 50.00.

b. Median partnership score

A median or middle score is the figure that a pair achieved in at least half of its partnerships. A captain and his number three batsman would probably prefer five consecutive 50-run partnerships than the same aggregate comprising successive stands of 0, 0, 0, 0 and 250. While Michael Slater and Greg Blewett enjoyed a respectable average partnership of 45.95, half of their stands realised fewer than ten runs, and they were a great example of a boom-or-bust pairing.

c. Value of partnership to team

As with individual innings, circumstances are important. A sizeable response to a first-innings deficit is far more valuable than one that builds on a big lead, or in a match destined to be a high-scoring draw. In summary, some runs have more value than others.

d. Strength of opponent

It’s useful to consider the quality of opposing bowling attacks, as well as performances relative to middle-order teammates and other countries’ batsmen. Australian batsmen prospered following WWI and WWII when England, South Africa and latterly India were rebuilding, and more recently during the late 1990s and early 2000s. In contrast they struggled in England prior to WWI, and during the 1950s against England, and between the late 1970s and early 1990s against West Indian and other strong pace attacks.

(Photo by Rebecca Naden – PA Images/PA Images via Getty Images)

e. Consistency

The ultimate test of a pair is performance over a long period, against a variety of opponents and in different conditions. To date only 19 duos have batted together 20 times, and only six of those have done so 40 times.

f. Match conditions, technological aids and player development

This criterion is particularly difficult to quantify.

Before WWI, sixes were often scored as fives or even fours. Before the 1940s, pitches were uncovered. Before the 1970s, protective equipment was minimal and outfields were slower. Before the 21st century, bats were less powerful and unroped boundaries were more distant.

However over time new deliveries have been invented, no-ball and LBW laws have been amended, pace bowlers have become fitter and stronger, fielding standards have risen, DRS has been introduced and opponents now feature greater fast-bowling depth.

g. Frequency of sizeable partnerships

Like median scores, this is an accurate measure of a pairing’s reliability. Over 144 years, pairings have averaged a century stand every 12 attempts and a 50-run partnership every fourth innings. The best of them have done so twice as regularly as that.

h. Combined individual batting averages

This is a useful measure of the likelihood of at least one of the pair amassing a large individual score. Hayden and Mike Hussey, Woodfull and Bill Ponsford, and Hayden and Simon Katich are the only three pairs in which each batsman averaged at least 50.00 when opening.

However such pairings do not guarantee success. Hayden and Mark Taylor amassed only 132 runs in ten attempts with an average partnership of 13.20, a highest stand of 35 and a median partnership of just seven.

So after considering all of these criteria, which pairings should be considered Australia’s best?

First: Bill Lawry and Bob Simpson

July 1961-January 1968, innings 62, average 60.94, median 39, highest 382

By almost every objective measure, Lawry and Simpson are Australia’s finest combination. Had Simpson not retired aged 31 and at the height of his powers, the duo could have continued for many more years. In their first match together, they shared a 113-run stand. Their very last partnership was worth 191 runs.

They were the only pair to endure for more than six years. They have the highest average partnership of any duo that has shared more than 16 innings. They achieved half-century stands more frequently than any other combination that faced more than 28 innings. Their combined batting average as openers of 102.66 has not been exceeded by any other duo that has shared more than 22 innings. And no other pairing that has opened more than 31 times has a higher median partnership figure.

(Photo by PA Images via Getty Images)

Their individual performances compare very favourably with those of other batsmen of the same era. They were the best-performed opening batsmen of the period, in which only Ken Barrington outscored Simpson. And they did so without protective equipment, power bats and shortened boundaries, and without playing against Bangladesh, New Zealand (against whom Slater-Taylor stands averaged 95.00, and Hayden-Langer 73.16), Sri Lanka (against whom Slater-Taylor and Hayden-Langer stands averaged 76.50 and 59.00 respectively) and Zimbabwe (against whom Hayden scored 380 in one innings).

Both of them could score quickly at times. Their nine century partnerships and a further five in the 90s included an Australian-record 382 in Bridgetown in 1965-66 at a rate of 3.21 runs per over, 244 against England in Adelaide in 1965-66 at the equivalent of 3.44 runs per six-ball over, and 191 against India at the MCG in 1967-68 at an equivalent of 3.88 runs per over.

While not every country’s fast-bowling attack during 1961-1968 was challenging, the leading wicket-takers against Australia nevertheless did include Fred Trueman (second), Peter Pollock (fourth), Joe Partridge (fifth), and Brian Statham (eighth) while Wes Hall and Charlie Griffith led the attack against which they scored 382.

The pair also produced some of its best partnerships after Australia had conceded a first-innings lead. They included stands of 113 in the face of a 177-run deficit at Old Trafford in 1961 after which Richie Benaud famously spun Australia to victory, 115 in response to a 61-run shortfall in Kolkata in 1964-65, and 120 when replying to a 200-run deficit against England at the MCG in 1965-66 to help secure a draw.

Second: Michael Slater and Mark Taylor

June 1993-January 1999, innings 78, average 51.14, median 30, highest 260

Slater and Taylor began their combination with 53 innings at an average of 62.51, and ten century stands including three in the fourth innings of a match.

As right-hander and left-hander, and aggressor and steady partner, they complemented each other perfectly. Their pairing commenced after Slater outscored Hayden in a virtual bat-off during the 1993 Ashes tour and played a large part in Australia dominating three Ashes series and finally regaining the Frank Worrell Trophy.

(WILLIAM WEST/AFP/Getty Images)

The pair claims second place in a close field, with the strength of opposing attacks a major consideration. The leading ten wicket-takers against Australia during 1993-1999 included seven high-quality opening bowlers in Darren Gough (first), Allan Donald (second), Courtney Walsh (third), Dean Headley (fourth), Curtley Ambrose (fifth), Andy Caddick (eighth) and Wasim Akram (ninth).

The duo invariably started series well. Their highlights included 260 at Lord’s in 1993 in their second match together, 176 in Rawalpindi in 1994-95, and 208 against England at the SCG in 1994-95 when chasing 449 for victory. The Gabba was the venue for partnerships of 99, 109 and 97 against England and Pakistan during 1994-95 and 1995-96, while the WACA yielded stands of 198 against New Zealand in 1993-94 and 228 against Sri Lanka in 1995-96.

Unfortunately their final 25 innings together yielded no further 100-run partnerships and an average stand of only 27.96, and their pairing ended with Taylor’s retirement at only 34 years of age.

Third: Matthew Hayden and Justin Langer

August 2001-January 2007, innings 113, average 51.88, median 31, highest 255

Australia’s most prolific pair enjoyed great initial success with 158 at the Oval in their first partnership, followed by four double-century stands at home during their next ten innings. They scored at an average rate of 3.80 runs per over. They were particularly productive in matches’ first innings, in which they recorded eight 100-run partnerships from 34 attempts with a median stand of 49. Against South Africa at home in 2001-02, they recorded 200-run partnerships in consecutive matches. It is no coincidence that while Hayden and Langer were prolific, Australia was dominant.

However a few factors count against a higher ranking. Many of their larger partnerships were achieved against relatively weak Indian, New Zealand, Sri Lankan and West Indian attacks, often at home. Among the ten leading takers of Australian wickets during 2001-2007, the only faster bowlers were Andrew Flintoff (second), Steve Harmison (third), Makhaya Ntini (fourth), Matthew Hoggard (fifth) and Jaques Kallis (eighth), not all of whom opened the bowling.

In summary, the early 21st century was a great time to be a top-order batsman. Eight of them averaged higher than Hayden’s 50.73 during the same period, including teammates Hussey and Ricky Ponting with 79.85 and 70.96 respectively. And for comparison purposes, Hayden had achieved little success when given opportunities during the preceding Slater-Taylor era, averaging only 21.75 himself over three series when batting with either of those partners.

(Photo by Hamish Blair/Getty Images)

Perhaps Gideon Haigh put it best at the time, writing in 2004 that “When Matthew Hayden made his Test debut ten years ago, he immediately had his hand broken by Allan Donald. Restored to the Test side two years later, he was humiliated by Curtly Ambrose and Courtney Walsh. After such an initiation, no wonder he feasts on the likes of Andy Blignaut and Sean Irvine.”

Like Hayden-Slater (but unlike Lawry-Simpson) the pair’s form eventually waned. Their final 22 partnerships yielded no century stands and an average of only 37.40. Hayden in fact enjoyed statistically more prolific pairings with Hussey (an average 65.43 runs) and Jaques (71.27) than he did with Langer.

Fourth: Geoff Marsh and Mark Taylor

January 1989-January 1992, innings 47, average 45.00, median 21, highest 329

This combination makes the shortlist due to the nature of the bowling attacks that it defied for three years. In most eras, only four to six of the ten leading wicket-takers against Australia were opening bowlers. But during this period, the 13 most successful bowlers were (in order) Malcolm Marshall, Curtley Ambrose, Courtney Walsh, Kapil Dev, Angus Fraser, Patrick Patterson, Devon Malcolm, Wasim Akram, Philip de Freitas, Manoj Prabhakar, Gladstone Small, Neil Foster and Danny Morrison. No slow bowlers, and few easy runs.

A number of other pairs achieved higher average partnerships, but none for so long and against bowling of such quality. The combination built on Marsh’s with David Boon, and was subsequently surpassed by Taylor’s with Slater. Interestingly while Marsh averaged a very modest 33.55 himself, he shared average opening stands of 46.77 with Boon and then 45.00 with Taylor.

There are other pairings that make us ask what might have been.

Nowadays a successful pair can anticipate batting together for many years and sharing the crease more than 100 times, just like Hayden and Langer. That was not always the case, as these examples show.

Reg Duff and Victor Trumper

January 1902-June 1905, innings 29, average 34.50, median 20, highest 135

Duff and Trumper was Australia’s first great combination, in its first great team, although by modern standards their statistics aren’t outstanding. They achieved three century and four half-century stands, and 966 runs in total. No previous duo had batted together more than 13 times, or yielded more than two 50-run stands, or amassed more than 285 runs in total. Additionally England’s attacks for its home series of 1902 and 1905 were arguably two of their strongest ever.

(George Bedlam, National Portrait Gallery)

They were also Australia’s fastest-scoring opening batsmen until Hayden nearly 100 years later, an asset when pitches were uncovered and overseas Tests were only three days long. Their partnerships included 135 from 157 balls in 78 minutes at Old Trafford in 1902 when Australia won by only three runs, and 129 from 175 balls in 88 minutes in Adelaide in 1903-04.

Their record would have been greater still had one of them not batted down the order in ten innings for tactical reasons, and if Duff had conquered his personal demons. Unfortunately he was an alcoholic who after scoring a century in his last Test aged only 26 died in hospital of a heart attack aged 33.

Sid Barnes and Arthur Morris

November 1946-August 1948, innings 13, average 54.31, median 38, highest 126

But for WWII, this pairing would have been far more prolific. Barnes made his debut in 1938 aged 22, while Morris scored a century in each innings of his first-class debut in 1940-41 aged only 18. Assisting the duo’s success was a lack of genuine fast bowlers in the England and India attacks of the period.

Their last two stands were 122 and 117, at Lord’s and the Oval respectively. Their combination would have continued after the Invincibles tour but Barnes’ rocky relationship with the Australian Cricket Board led to him never playing again. He was named for a Test as late as 1951-52, but the ACB refused to ratify his participation.

Colin McDonald and Arthur Morris

December 1952-May 1955, innings 15, average 63.27, median 55, highest 191

Morris’ early retirement at the age of 33 ended this combination. It commenced at home against South Africa, and concluded in the West Indies. In between against England in 1953 and 1954-55, the selectors instead tried Les Favell, Lindsay Hassett, Graeme Hole and Bill Watson with limited success against Trevor Bailey, Alec Bedser, Brian Statham, Fred Trueman and Frank Tyson.

(Credit: Swamibu/CC BY-NC 2.0)

Matthew Hayden and Phil Jaques

December 2005-January 2008, innings 11, average 71.27, median 69, highest 159

Hayden enjoyed success with many different partners, and statistically his most productive stands were with Jaques. Only two of them ended before reaching 48 and they were especially successful against Sri Lanka and India at home. Hayden’s retirement, Jaques’ back injuries and the selections of Katich and Langer restricted opportunities for the pair to bat together more often.

Phil Hughes and Simon Katich

February 2009-March 2010, innings 11, average 60.40, median 55, highest 184

Hughes and Katich were born 13 years apart, and each spent much time in the middle order or with a different first-wicket partner. When they did open together against South Africa, England and New Zealand they enjoyed great success. However they were quickly separated after Hughes’ debut series, and Katich’s career ended nine months later.

Simon Katich and Shane Watson

November 2009-December 2010, innings 28, average 54.39, median 47, highest 182

Katich and Watson opened together for only 13 months, but only six other duos were more prolific. Their first stand was 85 at Edgbaston, and their last 84 against England in Adelaide. In between the pairing yielded 174 and 132 against the West Indies in Adelaide and Perth, and 182 against Pakistan at the MCG. Katich never represented Australia again after injuring his Achilles tendon during that Adelaide match, despite playing at first-class level for a further three years.

Chris Rogers and David Warner

1 August 2013-25 August 2015, innings 41, average 51.32, median 27, highest 200

This combination ranks fourth in runs scored, and fifth in innings played. Unfortunately it didn’t commence until Rogers was aged 35, and ended when he retired two years later due to injury and age. Twenty-three of its partnerships took place against England, and it was also productive at home to India, and away to Pakistan and South Africa. The pairing was generally fast-scoring with Rogers’ own strike rate a healthy 50.60 runs per 100 balls. A high number of brief stands among many big ones contributed to a low median partnership figure.