“There are three kinds of lies: lies, damned lies, and statistics,” said the famous American author Mark Twain. Without any evidence at all, I choose to think that he did so immediately after watching a game of cricket in 1895 during his travels across Australia, as part of his worldwide speaking tour.

Part 1 analysed the quality of wickets taken by Australia’s leading 50 bowlers of all time.

It concluded that not only is it misleading to compare bowlers from different eras on raw statistics alone, but that it also can be to compare ones from the same era, and sometimes even teammate s.

That analysis found that opponents’ tailenders were dismissed most often by Australia’s slow bowlers and especially by leg-spinners, with Stuart MacGill, Shane Warne and Ashley Mallett particularly effective.

It also found that a number of pace bowlers with outstanding records against recognised batsmen dropped down the list of leading wicket-takers once lower-order ones were also included, with Jeff Thomson particularly affected.

In Part 2, I have expanded the exercise to include the 100 leading bowlers from other nations. The outcomes were almost identical, apart from wrist-spinners rarely featuring among other countries’ leading slow bowlers.

Overall, for the vast majority of bowlers, between 26 per cent and 31 per cent of the batsmen who they dismissed were tailenders. Those who took more were almost always slow bowlers, while those who took fewer were generally faster ones.

And clearly the more lower-order batsmen a bowler dismisses, the better his aggregate, average and strike rate will be.

Those who benefitted most from bowling to tailenders

The great English left-arm finger-spinner Wilfred Rhodes (for whom tailenders comprised 40 per cent of 127 wickets) is the only bowler with a higher proportion than MacGill, Warne and Mallett.

(Credit: Swamibu/CC BY-NC 2.0)

That level remained constant from his debut batting at number 11 in 1899, to when he bowled less regularly and with Jack Hobbs formed an outstanding opening batting pair during 1910-1921, finally retiring aged 52 after recording match figures of 2-39 from 44.5 overs in Jamaica in 1930.

He remains the most prolific bowler of all time, with 4204 first-class wickets.

Harbhajan Singh (36 per cent of 417 wickets), Lance Gibbs (36 per cent of 309) and Aubrey Faulkner (35 per cent of 82) round out the top-seven. Harbhajan was one of many skilled Indian off-spin bowlers, and his country’s most-frequent taker of tailenders’ wickets.

Gibbs bowled in the same style for the West Indies between 1958 and 1976. Faulkner was an outstanding South African all-rounder during the Golden Age of Cricket who bowled wrist-spin when the method was still in its infancy, and whose teams often contained four exponents of the craft.

Pakistan’s Wasim Akram (35 per cent of 414 wickets) takes eighth position in the list, and is the only faster bowler to feature in the top-12. At home, that figure rose to 39 per cent.

As his skills included pace and late reverse swing, it’s easy to understand him bowling regularly to tailenders, especially whenever he captained himself.

On a per-match basis, the leading removers of lower-order batsmen are England’s George Lohmann (2.06 wickets), Australia’s Clarrie Grimmett (2.03), Sri Lanka’s Muttiah Muralitharan (1.95) and England’s Sydney Barnes (1.93).

However, each also dismissed very high numbers of recognised batsmen, keeping their proportions of tailenders’ scalps low as a result.

(AP Photo/Eranga Jayawardena)

Those whose statistics suffered the most

Derek Underwood (for whom tailenders comprised only 24 per cent of 297 wickets, from 86 matches) is arguably England’s best-ever spin bowler. However, those figures do not do him justice.

In particular, his figure away from home (just 15 per cent of 152 wickets taken) is incredibly low for any type of bowler, let alone a slow one.

Although Underwood dismissed a recognised batsman 29 times more than Gibbs, his overall career total was 12 fewer than the latter’s then-world record 309. Had he dismissed lower-order batsmen with the regularity of other spinners, he would have gained at least another 40 wickets.

And had he not participated in World Series Cricket and rebel tours to South Africa, his final tally would have been higher still, and more accurately reflected his status in the game.

Harold Larwood (for whom tailenders contributed just 19 per cent of 78 wickets) is another all-time England great whose statistics appear underwhelming at first glance. A detailed look reveals why. In 1928-29 on his first tour to Australia, only 22 per cent of his 18 wickets were tailenders.

In his 11 other matches before he returned four years later, only one of his 27 wickets was of a lower-order batsman. Either he was kept fresh for recognised batsmen, or it was considered unsporting to bowl him at tailenders, or conditions genuinely better suited other bowlers.

Whatever the reason, the tactics for his use changed radically during the Bodyline series. England captain Douglas Jardine ruthlessly attacked all batsmen, and Larwood’s 33 scalps for the series included ten tailenders.

That average of two per match has been exceeded over an entire career by only two bowlers: Lohmann and Grimmett. It contrasts starkly with his previously sparing use against lower-order batsmen.

If Larwood had taken tailenders’ wickets in a proportion typical for faster bowlers (between 25 per cent and 30 per cent), then he would have realised at least 15 more wickets during his 21 matches, and at a better strike rate and lower average cost.

Finally, as a group, India’s opening bowlers fare particularly badly in any analysis of takers of tailenders’ wickets. Clearly being able to swing a new ball at medium-pace isn’t a skill that its captains have valued highly, late in an innings on the sub-continent.

Zaheer Khan (only 20 per cent of 311 wickets), Ishant Sharma (24 per cent of 303), Jagaval Srinath (24 per cent of 236), Karsan Ghavri (19 per cent of 109) and Irfan Pathan (19 per cent of 100) each usually surrendered the ball to a teammate who could turn it.

A country-by-country round-up

England

In the absence of good wrist-spinners, the most prolific takers of tailenders’ wickets have generally been finger-spinners.

In addition to Rhodes, leading left-arm slow bowlers have included Tony Lock (33 per cent of 174 wickets), Hedley Verity (33 per cent of 144), Johnny Briggs (33 per cent of 118) and Bobby Peel (29 per cent of 101).

However, England does feature a small number of faster bowlers with good records against lower-order batsmen. Ian Botham (31 per cent of 383 wickets), Fred Trueman (32 per cent of 307), Steve Harmison (32 per cent of 226), Barnes (28 per cent of 189), Lohmann (33 per cent of 112) and Tom Richardson (28 per cent of 88) also enjoyed regular success at the ends of innings.

India

As alluded to above, the role of dismissing lower-order batsmen has fallen almost exclusively to slower bowlers. Its few faster bowlers of quality have rarely gained late-innings hauls.

The leading bowlers have instead been Anil Kumble (32 per cent of 619 wickets), Harbhajan Singh (36 per cent of 417), Ravi Ashwin (33 per cent of 409), Ravindra Jadeja (33 per cent of 220), Erapalli Prasanna (31 per cent of 189) and Srinivas Venkataraghavan (35 per cent of 156).

Pakistan

As identified earlier, Wasim Akram (35 per cent of 414 wickets) is the highest-ranked fast bowler of all time, in terms of dismissing lower-order batsmen.

His best-performed compatriots are modern-era spin bowlers Abdul Qadir (33 per cent of 236), Yasir Shah (32 per cent of 235), Saqlain Mushtaq (35 per cent of 208) and Saeed Ajmal (34 per cent of 178).

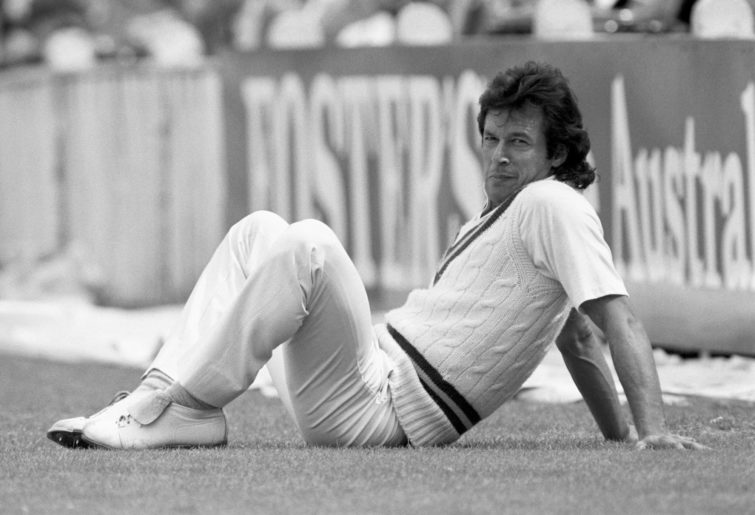

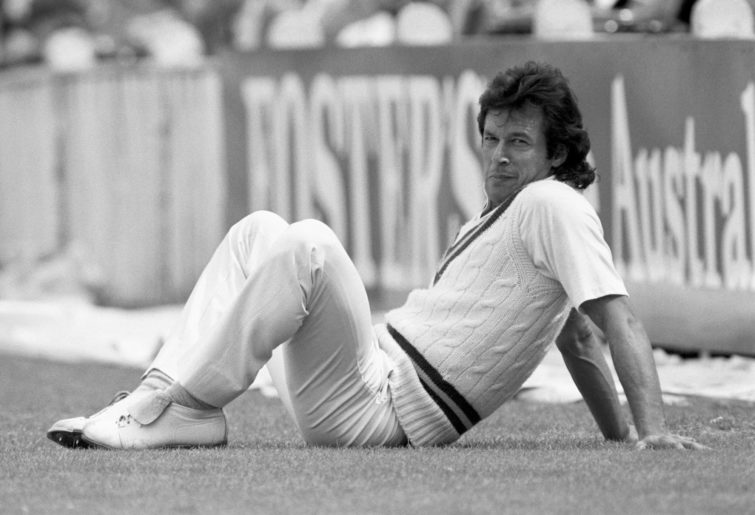

Conversely, attacking wrist-spinner Mushtaq Ahmed (only 24 per cent of 185) was not a prolific remover of tailenders. This may have been due to competing for opportunities with Shoaib Akhtar and in particular his captains Wasim Akram, Imran Khan and Waqar Younis.

Although Mushtaq dismissed a recognised batsman five times more than Saqlain, his overall career wicket total was 23 fewer.

Imran Khan is a giant of Pakistani cricket. (Photo by SandG/PA Images via Getty Images)

West Indies

Until the mid-1970s, the dismissal of lower-order batsmen occurred along traditional lines. Gibbs (36 per cent of 309 wickets) was the most prolific. Great fast bowler Wes Hall (only 22 per cent of 192) was, like Larwood, perhaps saved for opponents’ top-orders.

That method changed with the formation of pace-bowling quartets. The best-ever combination of Andy Roberts, Michael Holding, Joel Garner and Colin Croft made the taking of 20 wickets per match without a spin bowler not only possible, but expected.

Within that grouping, Garner (34 per cent of 259) and Roberts (32 per cent of 202) were the most regular removers of tailenders. However Croft (only 24 per cent of 125) was the pack’s unsung hero.

Per match, he took more wickets and dismissed more top-seven batsmen than any of the other three, despite the handicap of taking the fewest wickets of lower-order batsmen.

South Africa

The leading bowlers against tailenders have been paceman Dale Steyn (32 per cent of 439 wickets), off-spinner Hugh Tayfield (33 per cent of 170) and wrist-spinner Faulkner (35 per cent of 82). The opposite applies to Makhaya Ntini (only 24 per cent of 390) and Vernon Philander (25 per cent of 224).

Steyn took 49 more wickets than Ntini, and 47 of them were tailenders.

New Zealand

The most-prolific removers of lower-order batsmen have been Sir Richard Hadlee (30 per cent of 431 wickets) and Neil Wagner (32 per cent of 219).

In contrast, swing bowlers Chris Martin (just 22 per cent of 233), Richard Collinge (19 per cent of 116) and Dick Motz (23 per cent of 100) suffered from not being suited to taking wickets with an old ball, and/or bowling in weak attacks that rarely took 20 wickets in a match.

Sri Lanka

Muttiah Muralitharan (33 per cent of 800) dismissed fewer tailenders than Shane Warne, despite taking 92 more wickets in total. Rangana Herath (31 per cent of 433) inherited Murali’s role.

At the other end of the scale is medium-pacer Chaminda Vaas (only 23 per cent of 355). Herath took 78 more wickets than Vaas, and 55 of them were of lower-order batsmen.

Conclusions

Clearly, raw career statistics are not a fair means to compare bowlers, even after allowing for differences between eras. Harold Larwood, Derek Underwood, Colin Croft and Jeff Thomson are just four of dozens of examples, of bowlers whose bare figures do not reflect their quality.

Jason Gillespie and Joel Garner each took exactly 259 wickets, but Gillespie dismissed 25 more recognised batsmen. Similarly, Morne Morkel and Lance Gibbs each took 309 wickets, but Morkel’s victims included 25 more top-order batsmen.

Teammates Andrew Flintoff and Steve Harmison each took 226 wickets, but Flintoff dismissed 18 more top-seven batsmen. These are but three of many instances.

If the rankings of all-time leading wicket-takers were based only on those taken of top-order batsmen, then Anil Kumble would drop from third to fifth, Harbhajan Singh from 13th to 20th, Wasim Akram from 14th to 19th, and Gibbs from 31st to 38th.

Daniel Vettori, Fred Trueman, Dale Steyn and Rangana Herath would also fall. And in each case, his bowling average and strike rate would also suffer.

Similarly, James Anderson would rise from fourth to second, Makhaya Ntini from 18th to 11th, Malcolm Marshall from 20th to 15th, and Chaminda Vaas from 24th to 16th. Zaheer Khan, Ishant Sharma, Richard Hadlee and Curtley Ambrose would also rise. Additionally, each bowler’s average and strike rate would improve.

That’s not to belittle great slow bowlers such as Wilfred Rhodes and Stuart MacGill. Winning a match requires the taking of 20 wickets, and fielding a balanced attack is the most likely way to achieve it regularly.

If bowlers like them can end innings quickly while allowing their teammate s to rest, then they’ve significantly contributed to their side’s victories as well.

And without one a team will instead use a fast bowler like Garner, Harmison, Steyn, Merv Hughes or Neil Wagner for the same effect.

Footnote

Mark Twain was an avid baseball supporter, but also became a cricket follower. The sport was played in Connecticut, where he lived with his family, and he watched it when regularly holidaying in Bermuda.

A cricket ground in Washington D.C. is named Mark Twain Oval. And while I’m unaware of any exposure to cricket while in Australia, he did greatly enjoy attending the Melbourne Cup.