The recent Roar article ‘Lies and damn lies: cricket’s debatable statistics’ had me enthralled and sufficiently motivated to weigh in with my two bob.

I have always been fascinated by the polarising cricketers, those who spark polemics among the cognoscenti. I am thinking of Adam Voges, Dean Jones, Bill Ponsford and Matthew Hayden.

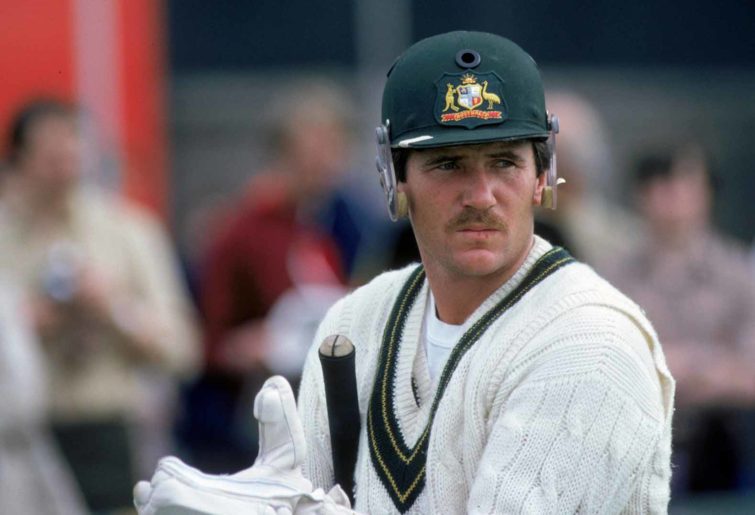

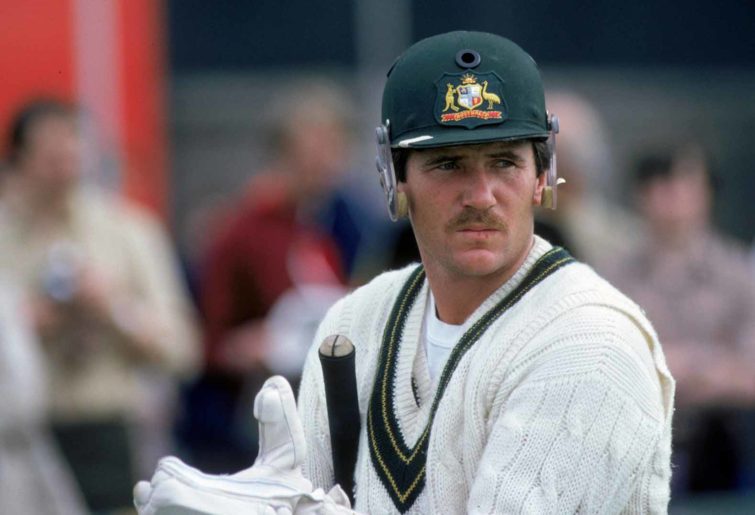

To me, the burly Queenslander is overrated and I am amazed how often his name appears in an Australian all-time XI. This is not to say that Hayden was not a very good player, he certainly was. Among his achievements, most compelling was his performances on the subcontinent, where he demonstrated a superb technique for dealing with the Indian spinners.

Another positive was the skill to concentrate for long periods, Hayden’s record of turning fifties into hundreds is ample proof and his conversion rate of 51 per cent (30 from 59) is among the game’s best.

The biggest problem that I have with Matthew Hayden is his record against high-quality pace. His performances against Curtly Ambrose, Ian Bishop, Courtney Walsh and Allan Donald leave much to be desired: 497 runs at 24.8 is a very poor return, especially given that Australia actually won nine of these 12 contests.

In the Ashes of 2005, I looked on with dismay as the destroyer from the previous series struggled with the reverse swing of Andrew Flintoff and Matthew Hoggard. The contrast with his demolition of Zimbabwe was like night against day, and I cannot escape the conclusion that Hayden’s rise to prominence, circa 2001, coincided with the retirements of the great quicks from the 1990s.

There are myriad players with the characteristic of scoring heavily when the going is good and then underperforming when things get tough. Half a dozen names come directly to mind: Adam Voges, Michael Clarke, Usman Khawaja, Graham Yallop, Bill Ponsford, and Matty Hayden.

(Lindsey Parnaby/AFP/Getty Images)

I like to call these players with the tide batsmen (WTT). Most cricketers have an element of WTT. For example, it is very common for batsmen to score their hundreds in an innings where at least one other colleague did the same. For Hayden, 60 per cent of his hundreds were like this (18 of 30), and for the others: Voges 80 per cent, Clarke 68 per cent, Khawaja 63 per cent, Yallop 75 per cent and Ponsford 86 per cent.

Nearly every player inflates their numbers to some degree. No one would question the value of Steve Smith to the Australian side but even he has made 14 of his 27 centuries in the manner described.

The big problem I have with using career batting average as a marker of a player’s ability is that this metric is easily influenced by large scores and not outs. Take a look at the highest scores made by Australians in Test cricket: 380 Hayden, 335* Dave Warner, 334* Mark Taylor, 334 Don Bradman, 329* Clarke, 311 Bob Simpson and 307 Bob Cowper.

Hayden and Warner made their scores against pop-gun opposition while Taylor, Simpson, Cowper and Bradman feasted on wickets so placid that their own bowlers stood very little chance of claiming 20 opposition wickets. The poor bowlers get such a raw deal by comparison. What is their equivalent of the 335*?

No matter how well they perform or how favourable the conditions, they are limited to just ten wickets, which they must share. This is why the bowling statistics are so much more accurate and reliable. When a guy average six wickets a match at something under 30, then no one can question their value and match-winning ability. It is very hard to inflate these numbers in the way batsmen can.

Of course, the best time to deliver a big hundred is when your team is in trouble. What could be more pleasing and valuable than Mike Hussey’s 134* at the SCG against Pakistan? Batting third, Australia trailed the visitors by as much as 206 at the half-way mark before Hussey, capably supported by Shane Watson (97), steered Australia to a highly commendable 381. Mitchell Johnson, Doug Bollinger and Nathan Hauritz then completed one of the most stunning comebacks in history.

(Photo by Tom Shaw/Getty Images)

Unfortunately for Australia, innings like Hussey’s are as rare as hen’s teeth. Recently, Roar guru matth examined the performances of Australian batsmen according to match outcome (win/loss/draw) and if I remember correctly, his method was to compare averages in each of the three categories. In the comments that followed, matth suggested refining the lost match category by omitting scores made in the game’s first innings. The idea being that at such an early stage, batsmen could have little or no idea that the match was about to head south.

Therefore, I have decided to run with his design but also introduce a modification of my own. If you are to study performances in circumstances where the match is going badly, doesn’t it make sense to include games that were heading south but eventually won? Should not Hussey’s 134* be included as a backs-against-the-wall performance?

The most objective way to achieve this, as far as I can see, is to look at the match situation at the halfway mark. If a team trails by 100 at this point, and goes on to win, then this match should be included. This event is rare. From 125 decided games, Australia has managed to win 12 and only three of these were against England.

Here are the results for 13 of our greatest batsmen in matches that were lost (excluding the game’s first innings), plus any of those 12 games where Australia won after they had trailed by 100 at the halfway mark.

| Batsman |

Matches |

Runs-dismissals |

Average |

Scores above 150 |

% above peers |

|

Star |

Peers |

Star |

Peers |

|

| VT Trumper |

16 |

1122-18 |

3228-130 |

62.3 |

24.8 |

214*, 185*, 166, 159, sticky wicket 74 |

151% |

|

| DA Warner |

26 |

1614-41 |

4833-209 |

39.4 |

23.2 |

|

70.10% |

| DG Bradman |

12 |

916-20 |

2834-102 |

45.8 |

27.8 |

167 |

64.60% |

|

| AR Border |

47 |

2072-61 |

8605-356 |

34 |

24.2 |

152* |

40.50% |

| SR Waugh |

36 |

1396-42 |

6184-251 |

32.2 |

24.6 |

|

30.90% |

|

| ME Waugh |

29 |

1115-39 |

5006-197 |

29.2 |

25.4 |

|

15.50% |

| ME Hussey |

19 |

854-26 |

3811-131 |

32.9 |

29.1 |

|

12.90% |

| SPD Smith |

27 |

1185-41 |

5485-210 |

28.9 |

26.1 |

|

10.70% |

| ML Hayden |

20 |

902-29 |

4124-141 |

31.1 |

29.3 |

|

6.30% |

|

| MJ Clarke |

31 |

1171-47 |

6022-227 |

24.9 |

26.5 |

|

-6.50% |

| RT Ponting |

35 |

1217-47 |

6455-232 |

25.9 |

27.8 |

|

-7.40% |

| GS Chappell |

19 |

723-27 |

3938-130 |

26.8 |

30.3 |

|

-13.00% |

|

| WH Ponsford |

10 |

268-15 |

2428-87 |

17.9 |

27.9 |

|

-56.20% |

Mindful to avoid a charge of subjective judgment (or damned lies), I will not attempt to draw any conclusions other than to elaborate on this particular approach and provide further detail on each of the great Australians.

Although this catch-all method of data collection is free from subjectivity, this is also a drawback. For one thing, approximately 20 per cent of scores collected in this way do not actually belong in a study of this kind. Sometimes, a team will lead until well into the second innings before collapsing to defeat.

Moreover, there are times when the position is so poor as to be beyond salvation. Chasing 650 with more than two days remaining, for example. I know from the career of Trumper that three of his 16 matches belong in one of these categories. Nevertheless, these glitches are relatively small and do not favour any particular player.

(George Bedlam, National Portrait Gallery)

Although Ponsford, Chappell, Ponting, Clarke and Hayden did not show any great proclivity for the come-from-behind situation, each has an impressive record in the first innings and through their front-running performances contributed greatly to their team’s success. A low ranking in this study just means that coming from behind was not their forte.

Nevertheless, each had at least one performance worthy of recognition. Ponsford’s day came in the famous Bodyline Test at Adelaide, when Harold Larwood was skittling the Australians like he was in a game of ten-pin bowling. Ponsford’s 85 was probably his bravest innings and made in a team total of just 221.

The classy Greg Chappell’s best effort arrived in 1977, during the disastrous tour of England. Leading an untested, rag-tag side, and with the spectre of World Series Cricket looming, Chappell showed peers the right way to play ‘deadly’ Derek Underwood on a turning Old Trafford deck. Despite his sublime 112, England still cruised to a nine-wicket victory.

Some may be surprised to see Ricky Ponting so low in these rankings but his great reputation was forged through fantastic first innings dominance.

(James Knowler/Getty Images)

However, credit where credit is due, Ponting played a tremendous captain’s hand to rescue the Australians in their first ever Test on Bangladeshi soil. His watchful and undefeated 118 secured a narrow three wicket win against the underrated minnows.

Actually, Ponting’s greatest on-the-ropes effort does not appear in this analysis. His masterly display in the third Test of the 2005 series led to a stalemate but Ponting’s 156 was the only thing that stood between a rampant England and victory.

I am disappointed with the record of Michael Clarke, at least as far as rescue acts are concerned. From 47 such innings, he passed 80 just once and was a perennial under-performer. Clarke’s best, 136 in the fourth Test of the 2009 tour, came when Australia faced a victory target of 522. Coming in at 3-78, which soon become 5-120, I am yet to be convinced that this hundred was anything more than the final thrusts of a dying fish.

Matthew Hayden’s greatest rescue effort was delivered in Sri Lanka, during the memorable 2003-04 tour. Australia began the series dreadfully as Muttiah Muralitharan ran amok with figures of 6-59. After the locals had posted a respectable 381, Australia was faced with the alarming deficit of 161.

Enter Matthew Hayden. Four hours later, the tables were turned on Murali and although Damien Martyn and Darren Lehmann also made hundreds, it was Hayden’s 130 that set the tone for the innings and possibly the series. Also noteworthy is the 72 he scored in the come-from-behind victory against Bangladesh, described above.

Steven Smith reminds me of Ricky Ponting in the way he performs so much better in the game’s first half. It is staggering to learn that just four of his 27 hundreds were produced in the team’s second innings.

(Mike Egerton/PA Images via Getty Images)

Smith best backs-against-the-wall effort is not included in this data set because the team won after trailing by 90, rather than at least 100. With this game included, Smith’s outperformance percentage moves to 19.2.

Few people will forget his 142 at Edgbaston in the first Test of the most recent series. Coming in at 2-27, and following on the heels of his first innings 144, Smith set about the England bowlers with his typical mix of quirky leaves, full-blooded drives and flicks through midwicket. If ever a contest was won singlehandedly, it was this Test at Birmingham. His other hundred came in 2016 against Sri Lanka when, together with Shaun Marsh, he put on 246 for the second wicket. Sadly, a fourth innings collapse meant the Sri Lankans took the series 3-0.

Apart from his spectacular and match-turning 134*, Mike Hussey’s next best effort was against England in the final Test of the 2009 series. Needing a world record 546 for victory and the Ashes, Hussey, Ponting, Watson and Simon Katich helped Australia to the promising score of 2-217 before Ponting and Clarke were run out.

Hussey fought on to be the last man out for a courageous 121. Another fighting effort of 90, against India in the final Test of the 2008-09 series kept Australia in the hunt after the locals began with 441. Although the visitors folded in the fourth innings to go down by 172 runs, Hussey had kept Australian hopes alive until well into the final day.

When you think of Mark Waugh and his most laudable innings, the mind is transported back to Port Elizabeth and the second Test of the 1996-97 series. After a paltry first innings of 108, in reply to South Africa’s 209, the visitors looked dead and buried. Rubbing salt into the wound, Adam Bacher and Gary Kirsten put on 87 for the first wicket before a remarkable collapse left the visitors with an unlikely 271 for victory.

(Steven Paston – EMPICS/Getty Images)

Waugh entered the fray with Australia teetering at 2-30 and fashioned a glorious 116, punctuated by 17 boundaries and a marvellous six, to give the Australians a two-wicket victory. The value of his innings can be measured by the size of the game’s second highest score – 55.

Ten months later, Waugh gave the Proteas further nightmares after his unflinching, six-hour 115* robbed the visitors of a drawn series. Another fine hundred against Mushtaq Ahmed, with his mix of leg breaks and googlies, kept Australia in the third Test in the summer of 1995-96. Unfortunately, on the spin-friendly SCG surface, no other Australian reached 60 and the Aussies went down by 74 runs.

Stephen Roger Waugh represents one of our finest backs-against-the-wall batsmen. Over a long career, his outperformance ratio of 30.9 per cent is remarkable and from 1993 onwards, the figure was 40 per cent. Waugh’s best match saw him deliver a pugnacious, undefeated double of 122 and 30 in a heartbreaking 12-run loss to England in Melbourne in 1998.

His 102 against the Poms in 2003, where his hundred come off the last ball of the day, kept Australia in the fight before Michael Vaughan’s 183 nailed our coffin shut. More typical though, was the defiant 40 or 50, where Waugh would remain unconquered.

Six times he was left stranded as the batting crumbled around him: 67* and 42* versus India; 60* versus South Africa; 30* and 42* versus England, and 45* versus the Windies. Arguably, Australia’s best interests may have been served if Waugh had batted higher than number five.

Defiance and the name AR Border go hand in hand. For those of who watched Australia’s struggles through the mid-1980s, Border was often the only thing standing between dignity and humiliation. In decided matches, Border is one of six Australians to have scored 150 after their team trailed by 100 at the change of innings.

(Adrian Murrell/Getty Images)

His 152* against Richard Hadlee at the Gabba could not save Australia from an innings defeat, by it did restore pride and hope. Border actually made four hundreds in these situations: 105 versus Pakistan, chasing 382 for victory; 126 versus the mighty West Indies, to give Australia a lead of 235; 124 in reply to India’s 237, in the match where Kapil Dev stole the game with 5-28 on the last day; and the 152 versus the Kiwis.

During the World Series Cricket saga, Border produced an undefeated double of 60 and 45 as Australia surrendered the Ashes. And four years later, he was left stranded on 62 with Australia just a heartbreaking four runs from victory. But Border is perhaps best remembered for an ability to snatch a draw when everything looked hopeless.

His unconquered double of 98 and 100 against the Windies at Port-of-Spain was like Mount Everest alongside the next best (48). Another 163 saved our bacon against India in the summer of 1985-86. During his best patch of 20 Tests, Border outperformed peers by 60.9 per cent.

It seems incongruous to place David Warner ahead of Don Bradman and I am unwilling to do so. For one thing, Warner has starred in a team that is yet to win a series in England, Sri Lanka or India. The average of Warner’s peers is comfortably the lowest in this list (23.1), behind Border and Trumper. So this is a case of outperformance in a mediocre side.

David Warner (Mike Egerton/PA Images via Getty Images)

That said, Warner has three memorable performances to his credit: fourth innings centuries against New Zealand (123*) and Bangladesh (112), where Australia fell agonisingly close each time, and a typically belligerent 97 in reply to South Africa’s 242.

Furthermore, it is Warner’s consistency that is most conspicuous and I note that from 42 innings, Warner has 14 scores between 41 and 77. Although somewhat counter-intuitive, it is actually better to score 160 followed by three ducks, than to score 40, 40, 40 and 40.

Remember, these are situations where the team is in trouble and scores of 40 or so will rarely cut the mustard. Nevertheless, in a come-from-behind situation, this dashing opener deserves a place among Australia’s top three.

It is not often that Don Bradman has to settle for second place but his greatest work was always in the mode of a front-runner. Be that as it may, he has two brilliant performances to his credit.

His 167 against South Africa in 1931 is the second highest score made by an Australian when trailing by 100 or more. Faced with a 160-run deficit, his 274-run stand with Bill Woodfull (161) broke the back of the visitors and ensured a comfortable win.

In some ways, Bradman’s hundred in the Trent Bridge Test of 1930 was an even greater performance. On a pitch that encouraged bowlers throughout, and where no other player would reach 79, his 131 (off 287 balls) was a masterpiece in concentration and brought the Australians surprisingly close to victory (they fell 93 runs short). From 20 innings, Bradman also made four half centuries (82, 71, 66 and 58) to outperform peers by almost 65 per cent.

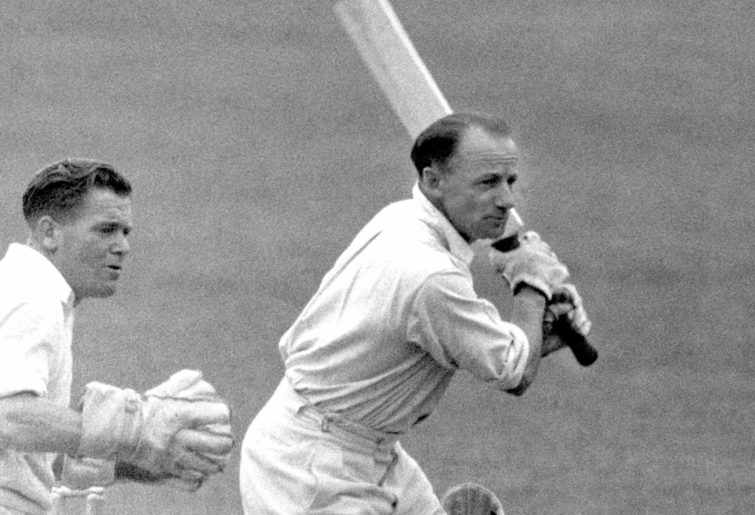

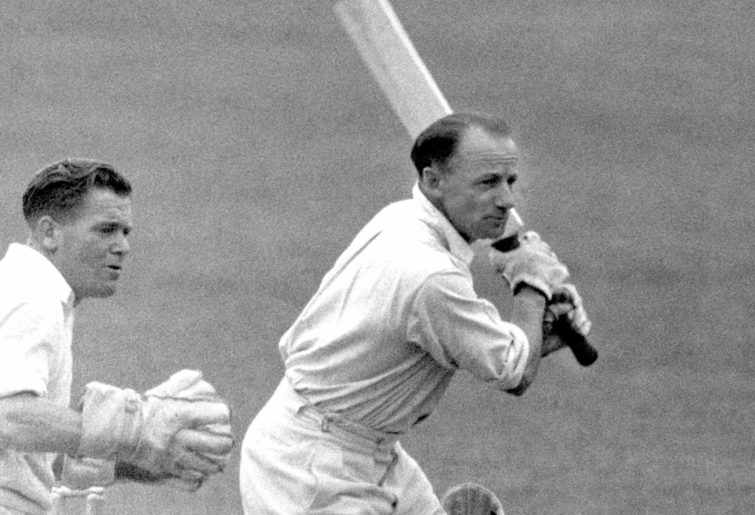

(PA Images via Getty Images)

By a country mile, Victor Trumper is Australia’s greatest backs-against-the-wall cricketer. He is as far ahead here as Bradman is in the regular averages. Twelve of Australia’s greatest batsmen, those featured in the table, had a combined 436 innings from which they registered two scores of 150 (Border and Bradman), or roughly one every 220 attempts. This gives you a sense of just how difficult it is to score 150 against the tide. And yet, from 20 attempts, Trumper did it five times.

At Sydney in 1903, his undefeated 185 converted a 292-run deficit into a lead of 193. When a catch went down at 4-82, the Poms looked vulnerable but they rallied to win by five wickets. Even so, most Englishmen agreed that if someone had stayed with Trumper, the match would probably have been lost.

Then in the very next game, Trumper was at it again. Batting first, England reached the comfort of 2-221 before rain turned the pitch into a quagmire. Their eventual 315 all-out meant Australia needed 116 to avoid the follow-on, a very tall order in the conditions.

Undaunted, Trumper came to the rescue, scoring 74 out of an Australian total of 122. On this diabolical surface, Trumper moved from three to 50 without giving a chance but at 7-93 the situation looked desperate for it seemed Trumper would again be left without a partner. In the slogging that followed, Trumper gave three chances before being last man out. Despite rolling the tourists for 102 in their second attempt, the wicket never recovered and Australia went down by 185 runs.

Four years later, Trumper’s 166 turned a 144-run deficit into a lead of 278. England fought stoically but eventually had to surrender 49 runs short. The second Test of 1910-11 was almost a carbon copy. From a total of 327 all out, Trumper’s 159 transformed a 158-run deficit into a lead of 169, at which point the inexperienced South African’s lost their nerve to capitulate by 89 runs.

Adelaide was the venue for the next match and this time the Proteas began with an overwhelming 482. Only Trumper’s 214* kept Australia in the hunt (next best was 54) but eventually they had to concede just 38 runs short of the required 379. Throw in a 63, 50 and sticky-wicket 35 and we have all of Trumper’s great get-up-off-the-canvas scores.

|

1901-02 |

1902 |

1903-04 |

1905 |

1907-08 |

1909 |

1910-11 |

1911-12 |

| Lost matches (three-day) |

|

2 |

|

13*, 11, 30 |

|

1 |

|

|

| Lost matches (timeless) |

2, 34 |

|

185*, 74, 35, 7, 12 |

|

63, |

|

214*, 28 |

2, 1*, 28, 5, 50 |

| Won after trailing by 100 |

|

|

|

|

166 |

|

159 |

|

It is worth mentioning that in the 22 innings in which he played, no other Australian reached 100. Also significant is that three-day Test cricket does not lend itself to authentic come-from-behind situations. In matches longer than three days, Trumper has 1065 runs at 76.1.

His scoring rate may also be of interest – 72.5. Finally, by his standards, Trumper had a poor final series (86 runs at 21.5). Before this, and after 14 years of Test cricket, Trumper was outperforming peers by 216 per cent. For that reason, when his team was on the ropes, Trumper’s wicket represented the equivalent of at least three specialist batsmen.

Of course, there is much more to batting than just the come-from-behind situation, and I would much prefer a player who dominated in the first innings. Nevertheless, it is worth asking if it is even possible for another cricketer to bat as well as Trumper did.

I hope this story gives others the chance to regard Trumper the way I regard Trumper, and the way a dozen former Australian captains have regarded Trumper.