I’m struggling to reconcile the leeway Nathan Buckley has enjoyed in the media.

In each of his first six years as coach, the club declined. In the latter four of those six, Collingwood missed the finals. In Buckley’s seventh year (2018), he coached Collingwood to a grand final loss, but since has gone backwards again.

Defending Buckley, Kane Cornes said that the AFL system got rid of coaches too quickly. Ten years is too quickly? Really? Others urged Collingwood to re-sign Buckley because he is the “best available”. Well, that’s true if you limit the pool exclusively to current coaches with long-term experience who are uncontracted.

Some might argue that Buckley’s predecessor, Mick Malthouse, was given a similar license. Malthouse also got ten years at the club despite the lack of a flag and was then re-signed for two more under the succession plan.

But after leading Collingwood to successive grand final losses in 2002-2003, Malthouse proactively spearheaded a rebuild, missed the finals just two years, and then guided Collingwood to finals 2006-2009 (with preliminary finals in 2007 and 2009), culminating with their premiership in 2010.

His coaching record each season (the position listed after finals) was 15th (from 16th), ninth, second, second, 13th, 15th, seventh, third, sixth, fourth, first and second.

Buckley’s has been third, eighth, 11th (from 18th), 12th, 12th, 13th, second, fourth, sixth and this year a bottom six-position looms.

How do those form lines compare?

Of course, you can’t make just straight comparisons. Eras are different. Circumstances are different.

However, there are factors that you can take into consideration in measuring a coach’s worth, and whether the club should persevere with them or should begin to look elsewhere.

In my opinion, there are enough concerns that exist about Nathan Buckley and his coaching that would worry me – and I know worry other supporters – moving into the future.

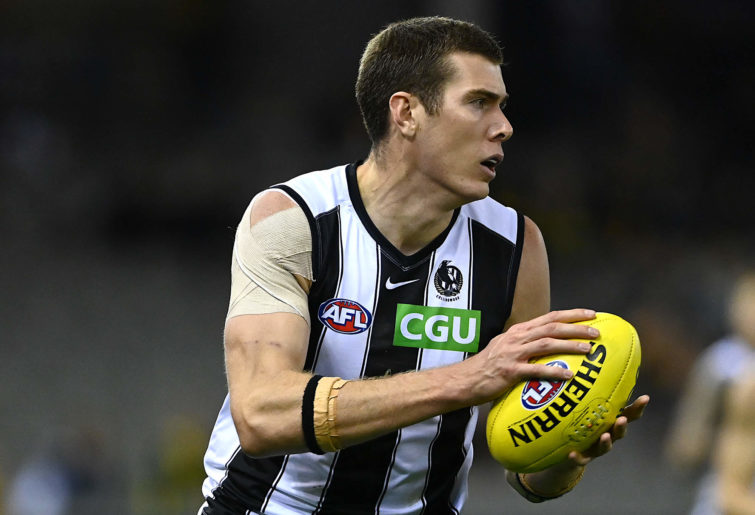

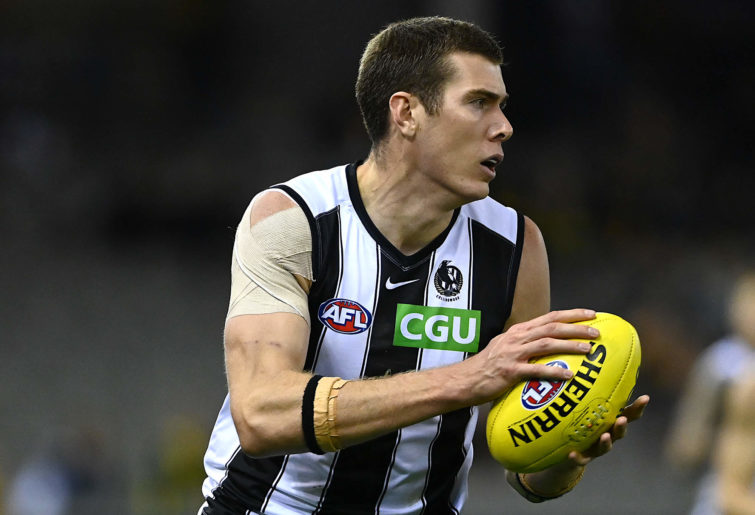

(Photo by Quinn Rooney/Getty Images)

1. The game plan

The biggest one.

Outside of 2018, Collingwood have played this short, indirect, glacial gameplan that keeps numbers behind the ball to minimise opposition damage. Common issues have been skill errors, poor decision making, lack of midfield synergy, atrocious forward entries (which has hurt every forward who’s played under Buckley) and (ironically given it’s such a defensive gameplan) vulnerability on the counterattacks.

We can’t just point at personnel as being the sole reason for the problems. We’ve seen seasons where personnel were available. I’d wager these issues were there in 2012-13 when Buckley had that premiership list, and they again resurfaced in 2019 and 2020. They ran rampant from 2014-17.

Football is about evolution. Premiers are often clubs that find an edge. Richmond’s done it with their chaos football. Bulldogs did it with their frenetic handball and slingshot counter-attack. Hawthorn did it with their precise kicking and rolling zones. Geelong did it with their globetrotting football.

(Photo by Quinn Rooney/Getty Images)

And Collingwood’s still trying to make something work that never has with any great consistency, and just isn’t that successful.

The one exception was 2018, when they went fast and direct. It’s a concern that they’ve never rediscovered, reproduced or even seemed keen to emulate that 2018 methodology, despite the evidence that it’s the one season they were a far better team than they ever were in the other nine.

So do I have confidence Collingwood will find a new game plan or that fast, wonderful 2018 football?

Based on the overwhelming evidence? No.

They prefer this game plan that tries to save matches and minimise damage rather than taking the game on and trying to make something happen.

2. Positional choices

A big query on Buckley’s teams have been selections – teams that have been top-heavy, or favoured certain players and readily dismissed others. You’d query that a number of games were lost at the selection table.

An extrapolation of this is where players play.

While players have to be versatile, and sometimes availability or a team’s needs may demand stopgap measures, there are choices Buckley and his assistants have made that raise queries.

Here’s a simple example from the game against Sydney: Buckley used Steele Sidebottom and Josh Daicos as centre-square midfielders.

Josh Daicos had a breakout season in 2020 as a winger. During the start of this season, he found himself being used as a defensive half-forward, while Jack Madgen was played as a winger. Both those were odd choices.

(Photo by Quinn Rooney/Getty Images)

Daicos is 178 cm and 76 kg. His strength has been his neat skills. Being used in the middle, he’s out-bodied and put in situations where he’s harried and it’s impacting his disposal. The same occurred to Adam Treloar during his time at Collingwood – a situation that Western Bulldogs’ coach Luke Beveridge has rectified by getting Treloar more on the outside.

Steele Sidebottom is 184 cm and 85 kg, and is another player recognised for his skills. He’s never been a bustling, physical, aggressive midfielder.

Now midfielders don’t necessarily all have to be beasts like Patrick Cripps. Taylor Adams is only 181 cm and 83 kg. But his DNA is to attack the contest and either fight for the ball or try to ensure that an opponent doesn’t win it. Adams plays with the fanaticism of a soldier diving on a grenade – exactly what you want at stoppages.

And midfielders do come in all shapes and sizes. In most cases, though, they’ll have a certain skill that’ll help them thrive in congestion, if not strength and/or bulk, then speed or x-factor.

In the case of Sidebottom and Daicos (and Treloar before them), they would seem better suited to wings where the ball could be fed out to them, and they could use their skills to construct offensives. That’s a means of maximising their strengths. Similarly with their running and endurance – they’re perfect linkers. But the way they’ve been used depreciates their strengths without genuinely gaining anything else from them to compensate.

If Jack Magden were to be trialled as a mid, given he’s 192 cm, 98 kg and has a certain aggression, he would seem ideal to be played in the centre where these traits would be assets.

Another example is Mason Cox: given his height and that he’s proven he’s a threat when the ball is delivered quick, it would seem logical to play him out of the goal-square and get the ball in there as fast as possible.

Instead, Collingwood allow him to be dragged up the ground, where his lack of agility and speed is exposed on the counter.

(Photo by Adam Trafford/AFL Media/Getty Images)

3. A lack of evolution

Something that’s been widely discussed is replacing the assistant coaches around Nathan Buckley.

Collingwood did this in 2018. Somebody credited with revolutionising Collingwood’s structure and gameplan was Justin Longmuir, which Brayden Maynard attested to in an article that Jake Niall wrote for The Age in September 2018). So while scuttlebutt and speculation is dismissible, substantiation from a player is not.

Fremantle appointed Justin Longmuir as coach in 2020. Matthew Boyd went with him. Garry Hocking was highly regarded, but – depending on who you ask – was either a victim of COVID cutbacks, and/or being too outspoken against the status quo. That’s meant Robert Harvey (2012-) and Brenton Sanderson (2016-) have remained.

The thought of appointing new assistants seems a tactic designed to legitimise Buckley’s retention. As senior coach, Buckley himself should be the driver of change. But from the outside looking in, it doesn’t appear that Buckley himself has sought that.

The coaches who enjoy longevity do so because their outlook on the game not only remains relevant, but also seeks an edge – just as Mick Malthouse pioneered ice-hockey-like rotations in 2007, and then developed The Press in 2010 as a means of defeating that era’s powerhouse, Geelong.

We just haven’t seen any evidence of that tactical innovation from Buckley and company, or that they even desire it.

4. Player management

When Buckley took over in 2012, he drove a cultural rebuild. Allegedly, there was a party atmosphere. But other narratives have also emerged about Buckley’s failure to connect to and deal with disparate personalities. This is a criticism that’s remained to this day, which has led to players being driven out.

Every coach will have their favourites, as well as players with whom they struggle. That’s every walk of life. We all respond differently to one another. You could point to any club and highlight examples of favourites and outsiders. But surely every attempt must be made to connect, nurture and groom (or rehabilitate) a player. That’s the senior coach’s job.

In his autobiography Accept the Challenge, Leigh Matthews talks about his time at Brisbane and how he and the sports psychologist broke players primarily into four categories and learned to handle players differently depending on which category they sat in.

During his time at Brisbane Lions during their three-peat era, Jason Akermanis’s relationship with his teammates fractured. Leigh Matthews sold Akermanis as a “consultant” to the rest of the playing group, a hired gun retained to do a job, rather than a teammate. It was a novel approach to reconcile a difficult situation during their premiership windows while retaining a valuable on-field asset.

Buckley was a brilliant player, but I never considered him naturally gifted. He was self-made, setting the bar, driving himself to reach it and then setting it higher and doing it all over. His singular focus and unrelenting drive propelled him to become one of the game’s best midfielders.

(Photo by Hamish Blair/Getty Images)

I can appreciate that he believes this attitude can be applied to everybody, and everybody will reap the rewards, but we all respond differently to stimuli. Hub life proved that. Certain players struggled to live, breathe and eat football 24/7.

It’s a coach’s job to find each individual’s specific stimuli, rather than compel everybody to unquestioningly adopt an approach that mightn’t work for them, or may even smother them. They’re not all the same, so you can’t treat them all the same.

How many players have Collingwood lost, or how many players are not producing their best, because Buckley is struggling to reach them in a way that’ll maximise their talents? And are there others who will suffer because of it?

5. Match-day coaching

Match-day coaching has rarely deviated from whatever has been prepared. The tone for so many games in the last ten years has been to stick with the status quo, even as the game is unravelling.

Lateral thinking usually comes too late and has predominantly consisted of throwing Darcy Moore forward when the margin is too big to overhaul.

(Photo by Dylan Burns/AFL Photos via Getty Images)

The fallback has often been simply to ask more of the players, but this is flawed thinking that presupposes that the players either haven’t been giving their best or that there is some untapped well of effort they can mine at will.

How often can you do this? If this is your regular contingency, how long before it drains players? How long before they have nothing left to give? Or the message wears thin? And how effective a tactic is it if the opposition are doing exactly the same thing?

Where are the moves that might ruffle the opponent’s match-ups? Where are the shifts in strategies to punch through the opposition’s tactics? Where is anything different to produce a different outcome?

We don’t get any of it.

It simply becomes about a single request: “Try harder.”

Conclusion

This is a small sampling of issues.

We’ve seen them all before. We’re seeing them now. It’s astonishing the regular media are overlooking genuine flaws in Buckley’s coaching and championing his reappointment. The evidence is there. There are nine years of it.

I loved Nathan Buckley the player. I wanted him to coach. But I’ve begrudgingly conceded he’ll never be the coach I – and so many others – expected.

Imprinted on all these queries is a simple unassailable truth: the lack of change.

Going forward, how will that offer anything but more of the same for Collingwood?