A lucky captain can call upon four Test-class bowlers, or at least a genuine fifth bowler who doesn’t weaken his batting line-up.

For any other skipper, part-timers must suffice. Following my article on tail-enders’ batting, this one will focus on batsmen’s bowling.

In the current era such a player is rarely entrusted with ten overs in an one-day match or even four in a Twenty20 game. The stakes are too high, conditions too favourable for willow-wielders, and apparently batting now too demanding to allow secondary employment.

But in past eras, many batsmen bowled regularly at grade and state level, and respectably in Test matches. They enabled pacemen to rest, and the wickets that they took were just as valuable as those taken by specialist bowlers.

Until the 1970s, formats encouraged batsmen to hone their wrist-spinning skills. The limited-overs game’s subsequent rise then made a fifth bowler essential rather than optional. However he was almost always a medium-pacer such as Simon O’Donnell, Tom Moody, or a Waugh.

During the 1990s, things changed again. A dominant four-man attack was built around Glenn McGrath and Shane Warne. Part-timers became less needed, rarely practised due to risk of injury, and only occasionally played and bowled in club and domestic cricket. Support staff with ball-launchers replaced them in the nets. The Waughs, Moody, Greg Blewett, Ricky Ponting and Damien Martyn bowled less and less.

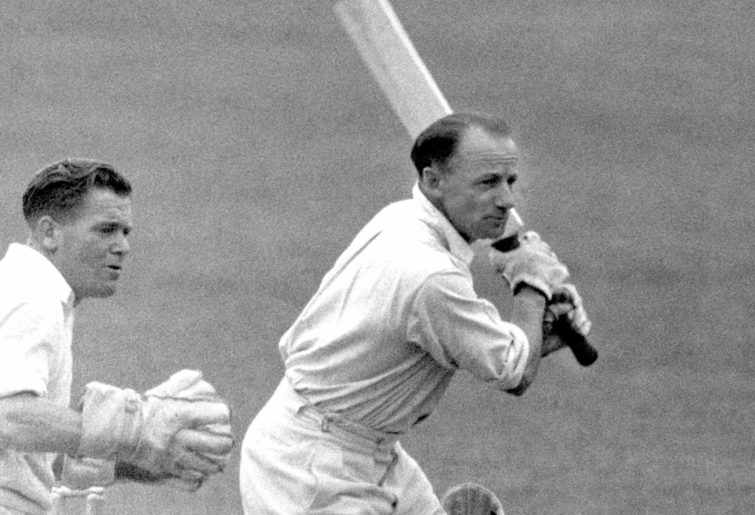

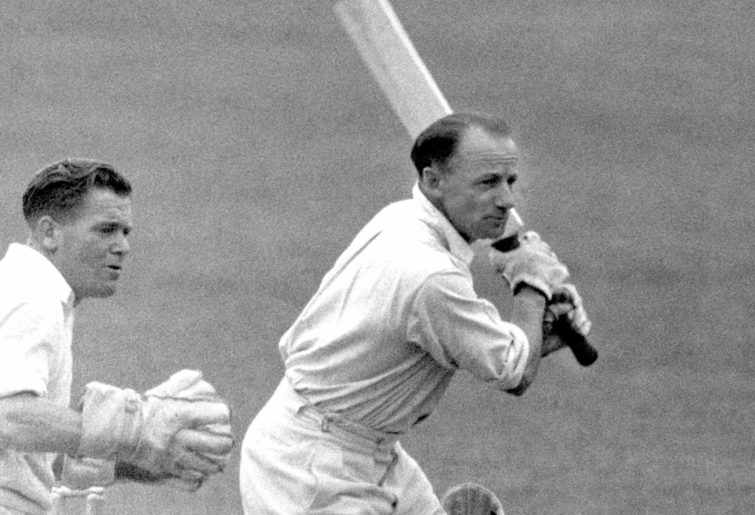

Admittedly the risk of injury is real. At the Oval in 1938, Don Bradman sprained an ankle while bowling leg spin, and was carried from the field. Finally deeming the home team safe from defeat, captain Wally Hammond declared at 7-903 three overs later. Bradman was unable to bat, and Australia’s humiliating defeat by an innings and 579 runs helped sow the seeds for his obsessive leadership of the Invincibles ten years later.

(PA Images via Getty Images)

Part-timers and genuine all-rounders

Who have been Australia’s most successful part-time bowlers? To answer the question, I’ve set (admittedly subjective) criteria to differentiate between genuine all-rounders, bowling all-rounders, and batsmen who bowled.

Genuine all-rounders capable of being selected as either batsman or bowler are ineligible. That rules out Keith Miller, Monty Noble and George Giffen, but no-one else. Bowlers who rarely if ever batted in the top six are also ineligible. So by a process of elimination, a part-timer is one who fulfils the following criteria.

a) Averaged fewer than 20 overs or 1.5 wickets per match. This eliminates Warwick Armstrong, Ken Mackay and Greg Matthews, and every bowling all-rounder.

b) Bowled in fewer than three quarters of opponents’ innings. This excludes Shane Watson, Andrew Symonds, Mitchell Marsh and Stan McCabe, who almost always bowled.

c) Was mostly used only after at least four other bowlers had been tried. This rules out Greg Chappell, Doug Walters and Charlie Macartney. Admittedly this disadvantages those whose teams regularly included only two pacemen.

The best part-timers

Bob Simpson

62 matches, 1957-68 and 1977-78, 4869 runs at 46.81, ten centuries, highest score 311

Simpson is one of Australia’s greatest ever opening batsmen and slip fieldsmen, and most successful coaches. He was also a very useful leg spinner. Based on the above criteria, he is his country’s finest part-time bowler to date.

He took 71 wickets, from an average of 19 overs per match. He achieved those figures despite bowling in only 84 innings, and being one of the first four bowlers used only 15 times. His career strike rate was 96 balls.

(Photo by Don Morley/Allport/Getty Images/Hulton Archive)

Restrictions on his use included a leg-spinning captain in Richie Benaud, and a succession of wrist-spinning teammates including Lindsay Kline, Norman O’Neill, Johnny Martin, Ian Chappell, David Sincock, Peter Philpott, Keith Stackpole and Johnny Gleeson, and later Tony Mann and Jim Higgs. As noted earlier, the pre-ODIs generation was a productive one for that style.

It also didn’t help his cause that his teams included so many capable all-rounders including Benaud, Mackay and Alan Davidson. As a result they could include more than four front-line bowlers without dangerously weakening their batting.

At Old Trafford in 1961, Simpson helped restrict England’s first innings to 367 with figures of 4-23 after being the fifth bowler used. Despite conceding a 177-run first-innings deficit, Australia retained the Ashes with a remarkable win. He also took four catches and scored a half-century.

At the SCG in 1962-63, he was the fifth bowler used in England’s first innings and took 5-57 as it slumped from 3-201 to 279 all out and ultimately lost. His 91 and three catches also played no small part in the victory.

In his last match before retiring from international cricket for ten years, he captained Australia against India at the SCG in 1967-68, and used himself only as the sixth bowler in each innings. Despite that he still took 3-38 and 5-59 in a 144-run win, while also snaring five catches.

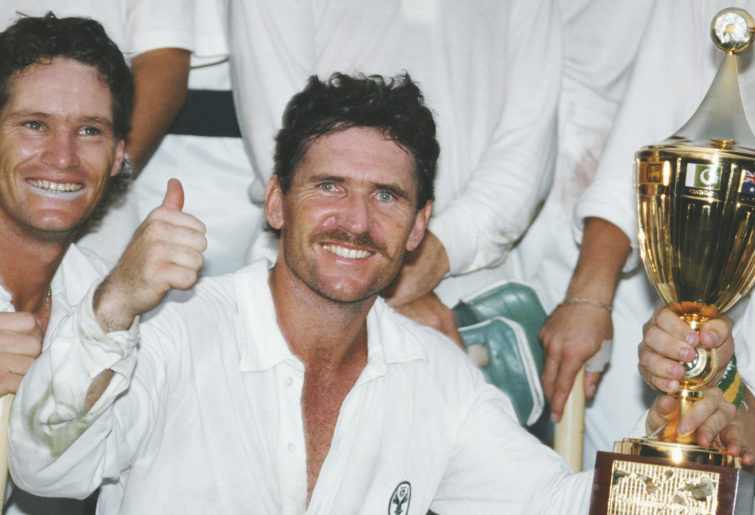

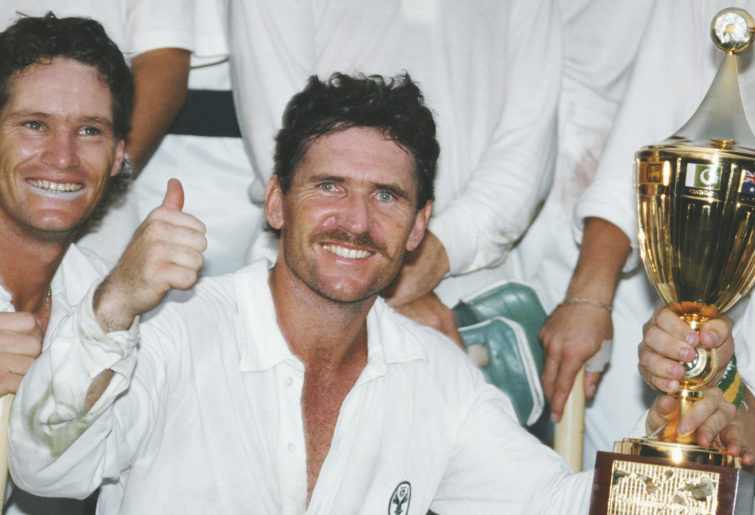

Allan Border

156 matches, 1978-1994, 11,174 runs at 50.56, 27 centuries, highest score 205

Modern great Border led by example with the bat and as captain, but was a reluctant left-arm orthodox spin bowler. He bowled in only 98 innings, took a wicket in only 22 of them, and averaged fewer than five overs per match. He took 39 wickets in total, with a career strike rate of 103 balls. His claim to fame as a bowler is based on one outstanding performance.

At the SCG in 1988-89, he almost single-handedly demolished the West Indies with 7-46 as the fifth bowler used, followed by 4-50 as his team’s sixth one. He also scored 75 and 16 not out in a comprehensive victory over a seemingly unbeatable opponent. Prior to the match, his career tally had been a mere 16 wickets from his first 100 games.

(Photo by Allsport/Getty Images)

Another noteworthy performance was in Georgetown in 1990-91. He introduced himself as the innings’ sixth bowler, and bowled 30 overs to take 5-68 in a West Indies total of 569. His first wicket came with the home side’s score at 1-307, to break a 297-run stand between Desmond Haynes and Richie Richardson.

Bob Cowper

27 matches, 1964-1968, 2061 runs at 46.84, five centuries, highest score 307

Left-handed batsman Cowper was a member of Simpson’s teams, and they complemented each other well. His straightish off breaks yielded 36 wickets at a strike rate of 83 balls. He delivered an average of 18 overs per match, and had a reputation for breaking partnerships.

Against India at the Gabba in 1967-68, he was the sixth bowler used in each innings and bowled 54 eight-ball overs to take 3-31 and 4-104. He also scored 51 and 25, in a match that Australia won by only 39 runs. The visitors were 5-310 chasing 395 before Cowper and Gleeson removed their tail.

The following week at the SCG he was promoted to fifth bowler and took 1-21 and 4-49, to go with personal scores of 32 and 165. Australia won again, defending a target of 341.

At Old Trafford in 1968, when England batted first he was the fifth bowler used and took 4-48. Combined with 2-82 in its second innings, 37 runs and two catches, it gained him the man of the match award in a comfortable win.

At only 29 years of age he retired from cricket to pursue a business career, later becoming a multi-millionaire and moving to Monaco.

Michael Clarke

115 matches, 2004-2015, 8643 runs at 49.10, 28 centuries, highest score 329 not out

Clarke, like Border before him, was a reluctant left-arm finger spinner. He bowled in only 65 innings, and took a wicket in only 17 of them. While averaging fewer than four overs per match, he still took 31 wickets at a very respectable strike rate of 78 deliveries.

His first noteworthy performance took place in Mumbai in 2004-05. To that point he had bowled just one over in Test cricket. On a poor pitch he was tried after four specialist bowlers had failed, and took 6-9 to trigger an Indian collapse from 4-182 to 205 all out. Unfortunately Australia then lost by 13 runs when chasing a mere 107 for victory.

(Nicky Sims/Getty Images)

At the SCG three years later India appeared to have forced a draw by reaching 7-210 with a handful of overs remaining. Clarke was introduced as the sixth bowler, and took 3-5 from 1.5 overs as Australia won with nine minutes of play remaining. Unfortunately the result was overshadowed by poor umpiring and player behaviour.

He made his last major contribution four years later in Roseau as captain, when the West Indies chased 370 for victory. He introduced himself as the fifth bowler in only the 16th over, and immediately dismissed Kraigg Brathwaite. His figures in a 75-run win were 5-86 from 23 overs, the most that he had ever delivered in a single innings.

Steve Waugh

168 matches, 1985-2004, 10,927 runs at 51.06, 32 centuries, highest score 200

An outstanding captain and batsman, Waugh is a difficult player to categorise. His overall career statistics belie any claim that he was a genuine all-rounder. Injuries, captaincy, a quartet of dominant bowlers and a desire to excel as a batsman minimised his contributions with the ball.

His medium-pacers yielded 40 wickets in his first 24 matches, only 26 more victims in his next 41 games, and then a mere 26 wickets from his final 103. He took 92 wickets with a strike rate of 84 balls, and averaged eight overs per match. However he didn’t bowl at all in 11 series including the Ashes of 1994-95 and 2001.

In Adelaide in 1993-94 after scoring 164, he was the sixth bowler used in South Africa’s first innings and took 4-26 from 18 overs to inspire a comfortable win. At Cape Town six weeks later, he was the fifth bowler introduced and took 5-28 from 22.3 overs, as well as scoring 86 in another win. Later in the same series in Durban, his 3-40 from 27.2 overs as the fifth bowler used restricted South Africa to 422, and his innings of 64 further helped to force a draw.

(Credit: Ben Radford/Allsport/Getty Images)

The more-than-part-timers

Deciding whether a bowler is a part-time one is an inexact science, and these three players could be considered unlucky to have missed the shortlist.

Doug Walters

74 matches, 1965-1981, 5357 runs at 48.26, 15 centuries, highest score 250

Cavalier batsman Walters took 49 wickets and averaged eight overs per game, delivering out-swingers with a low-slung action. He enjoyed a reputation as a partnership-breaker, and his career strike rate of 67 balls was outstanding.

Counting against his designation as a part-timer is the way in which he was used. In 72 innings he bowled first change 24 times, and second change a further 18. That included the first 13 innings in which he bowled, and later 12 consecutive innings in which he bowled during 1973 and 1974. Contributing to that strategy was the regular selection of a pair of spinners, leaving him as his team’s third fastest bowler.

Subsequently Australia fielded a three-man pace attack drawn from Dennis Lillee, Jeff Thomson, Max Walker and Gary Gilmour. Greg Chappell became the preferred support bowler and an ageing Walters bowled less regularly.

While he didn’t remove top-order batsmen particularly frequently, the ones that he did dismiss were often well set. They included three who had reached three figures, and a further nine who had passed 50.

His best figures were 5-66 against the West Indies in Georgetown in 1972-73 when bowling second change. He took four wickets in an innings on three other occasions, including 4-53 against England at the MCG in 1965-66 after being the third bowler used.

Greg Chappell

87 matches, 1970-1984, 7110 runs at 53.86, 24 centuries, highest score 247 not out

Captain and all-time great batsman Chappell inherited Walters’ role. He took 47 wickets and delivered an average of 11 overs per game, bowling medium pace with an upright action. Like Walters, initially he was often used as a front-line bowler.

During the 88 innings in which he bowled, he took the new ball twice, and was introduced at first change or second change 49 times. It’s difficult to imagine someone of his type doing that nowadays. A career strike rate of 111 balls suggests more of a holding role than a strike one.

(Photo by Matt King – CA/Cricket Australia/Getty Images)

His best innings figures were 5-61 against Pakistan at the SCG in 1972-73 when introduced at second change, 3-54 against New Zealand at the same ground a year later after opening the bowling following an injury to Max Walker, and 3-49 in Karachi in 1979-80.

Charlie Macartney

35 matches, 1907-1926, 2131 runs at 41.78, seven centuries, highest score 170

Aggressive top-order batsman Macartney was also a fine left-arm orthodox spin bowler. He took 45 wickets, and delivered an average of 17 overs per game for a wicket every 79 deliveries. He achieved his greatest successes prior to WWI, later focusing instead on his batting.

Reflecting the era’s strategies and pitch conditions, he took the new ball in 15 of the 45 innings in which he bowled, and in 30 of those innings was one of the first four bowlers used. His best figures were a match-winning 7-58 and 4-27 at Leeds in 1909 as an opening bowler, and 5-44 at Cape Town in 1921-22 after being introduced as first change.

Part-timers take many forms

Perhaps unsurprisingly, relatively few batsmen have bowled medium pace. It’s a strenuous activity, unlike standing in the slip cordon. Apart from those named earlier, the only others worth considering were Tom Horan, Jack Ryder, Sam Loxton and Greg Blewett.

Many have bowled finger spin with Darren Lehmann and Marcus North also enjoying success. In Colombo in 2003-04, left-armer Lehmann added to his innings of 153 with 3-50 and 3-42 from third change to cement his man of the match award in a 121-run win. Against Pakistan at Lord’s in 2010, off spinner North took 6-55 when used as sixth bowler in a 150-run win notable for the debuts of Tim Paine and then-specialist spin bowler Steve Smith.

Wrist-spinning batsmen have featured ever since Harry Trott started the trend in the 1890s, with Simpson and Armstrong the standouts. What characterises the style is better-than-average strike rates.

Left-armer Michael Bevan had a career strike rate of 44 balls, the best of any Australian who has taken more than one wicket. His 29 victims from 18 matches included 4-31 and 6-82 against the West Indies in Adelaide in 1996-97 when picked as a specialist bowler and used at first change. He also scored 85 not out from number seven in that match as Australia won by an innings and 183 runs.

Fellow left-armer Simon Katich’s strike rate of 49 deliveries places him second only to Bevan among part-timers, and third among all Australians with more than one wicket. He bowled in only 25 innings in 56 matches, and averaged only three overs per game. In his second match he took 6-65 against Zimbabwe at the SCG in 2003-04 to go with an innings of 52 in a nine-wicket win.

Trott sits fourth with a wicket every 65 balls while Marnus Labuschagne (every 68 balls), Steve Smith and Norm O’Neill (each 81 balls) have also enjoyed success.

(Photo by Francois Nel/Getty Images)

Labuschagne took 3-45 and 2-74 against Pakistan in Abu Dhabi in 2018-19, and Smith 3-18 and 1-65 at Lord’s in 2013. At Port of Spain in 1964-65, O’Neill was the eighth bowler used and took 4-41 to trigger a West Indian collapse from 3-365 to 429 all out.

Ian Chappell and Keith Stackpole also contributed leg spin, with 20 and 15 wickets respectively. And at the SCG in 1970-71 teammate Ken Eastwood was the sixth bowler tried, bowled five overs of left-arm wrist spin, and dismissed England’s first-drop batsman Keith Fletcher cheaply. Unfortunately he also scored five and zero opening in place of deposed captain Bill Lawry, and was never selected again.

The best overseas part-timers

The West Indies’ Carl Hooper and Sri Lanka’s Sanath Jayasuriya are the only part-time bowlers with better statistics than Simpson.

Off spinner Hooper played 102 matches and dismissed 114 batsmen. In Kingstown in 1997, he was the fifth bowler used and took 5-26 to trigger a Sri Lanka collapse from 2-151 to 222 all out. Combined with scores of 81 and 34, it earned him the man of the match award. He also took 5-40 against Pakistan at Port of Spain in 1992-93, when he was the sixth bowler used.

Left-arm orthodox spinner Jayasuriya has a record almost as impressive. In 110 matches he took 98 wickets. In Colombo in 2004 he was introduced to the attack only after five other bowlers had been used, and took 5-34 to reduce South Africa from 1-109 to 189 all out and help secure a 313-run victory.

The most remarkable one-off performance

Border’s achievement aside, England’s Alfred Lyttelton warrants mention. At the Oval in 1884, Australia reached 6-532. Captain Lord Harris threw the ball to Lyttelton in desperation. He removed his wicketkeeping gloves and from nine four-ball overs took 4-8 to end the innings. Having earlier bowled three overs of medium pace, his final figures were 4-19.

Making the circumstances even more remarkable, he took his wickets with underarm lobs, while still wearing his pads. For each intervening over bowled from the other end, he re-donned his gloves and resumed his place behind the stumps. He was the first wicketkeeper to take a wicket, and in fact to even bowl, in a Test match. Unsurprisingly, his figures are still the best ever by an 11th bowler.

Conclusion

Whether a bowler is a good part-timer or a modest all-rounder is a matter of opinion. Stricter criteria would have ruled out Simpson and Cowper. More leeway would have admitted Walters.

However it is clear that part-time bowlers can win matches, just as tail-enders can score match-winning runs. One in a team is almost always essential, and two are better still. They can turn a good side into a great one, especially if they can take wickets rather than just provide fast-bowling teammates with rest breaks.

Part-timers are also easier to find and develop than genuine all-rounders, who are once-in-a-generation players. Test matches played back-to-back, rest days no longer scheduled, and pacemen rotated due to workload make multi-skilled batsmen more valuable than ever.

Many players good enough to become Test-quality batsmen and fieldsmen clearly have the natural ability to also become capable bowlers. Hopefully the current duo of Labuschagne and Cameron Green will cement their places in the batting order, while also being as successful with the ball as Cowper and Simpson in the 1960s, Walters and Greg Chappell in the 1970s, and the Waugh brothers in the 1990s.