Alternate histories are all over YouTube, and some of them are quite credible and therefore fascinating.

What if Germany, upon conquering Western Europe, including France, had pressed on in the second half of 1940 and launched Operation Sea Lion (the plan to invade, conquer and occupy Great Britain)?

What if the Confederacy had won the American Civil War? How long would slavery have then lasted in those southern states with the ever-advancing mechanisation in agriculture?

There are many others.

Have you ever given any thoughts to alternate histories in the cricketing world? I have. Here are a few.

1. Eddie Paynter does not rise from his hospital bed in Brisbane, February 1933

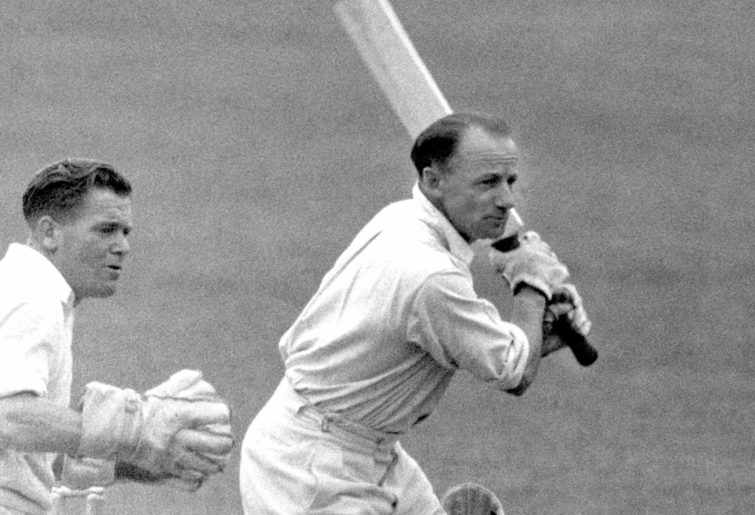

For those who don’t know the specifics, this was the fourth Test of the bodyline series, and England led 2-1 going in. Australia batted first on a flat pitch and for a rare time in the series, bodyline was tamed on the first day.

A first day stumps score line of 3 for 251 actually amounted to a mini escape for England, as the home side had been one for 200. On the second day, the English bowlers hit back to restrict Australia to 340, Don Bradman adding only 5 to his overnight 71.

The previous day, Eddie Paynter had collapsed in the excessive heat and been taken to Royal Brisbane Hospital, a bit over six kilometres from the Gabba. Since 1933, a much closer public hospital has been built, the Princess Alexandria in a neighbouring suburb of Annerley.

From 0 for 114 in reply, England suffered a mini-collapse to 3 for 157 with both openers, Douglas Jardine and Herbert Sutcliffe as well as star batsman Walter Hammond all gone. They further slumped to 6 for 216, the Australian spinners Bill O’Reilly and Bert Ironmonger were running riot.

It was at this point that Jardine summoned Paynter from his hospital bed and for those that don’t know, he earned the heartfelt admiration of the home crowd by batting four and a half hours for an unconquered 83, in heat and humidity just as oppressive as the previous day, to take England into a slender lead of 16 on first innings.

Then Australia folded for 175, Harold Larwood having rediscovered his mojo to snare the key wicket of Bradman for 24 to finish with 3 for 49 from 17 and a bit overs, and England knocked off the 160 required with just four wickets lost to take the Ashes with a Test to spare. Paynter hit a six to secure victory.

But what might have happened had Paynter remained in hospital for whatever reason? Perhaps Jardine yielded to Plum Warner’s express orders forbidding it, or maybe Jardine never came up with the idea, or what if Paynter just didn’t feel he could do it. What if the taxi didn’t get back to the Gabba in time, or even hospital staff refused to allow him to leave?

(PA Images via Getty Images)

Well, it’s a reasonable assumption that the English tail would not have withstood the rampant Aussie spinners for long, so a lead of 100 or more would have been on the cards.

More importantly, the Australian team would have spent four fewer hours in the field in those extreme weather conditions, and the English bowling attack would have had four less hours to put their feet up.

One would also have to think that the home crowd warming completely to Paynter during those four and half hours at the crease would have completely demoralised the Australians, who up until that point had enjoyed nothing but partisan condemnation of the England team as a whole due to the controversial tactics of Larwood and the support pacemen.

So, in the alternate scenario, with Paynter’s innings never happening, and a forced closure by England at 9 down and the aforementioned hypothetical lead of over 100, the Australian batsmen come out and put the England bowlers to the sword and run them completely ragged.

By batting for a couple of days in the exhausting heat and the strain is too much for Larwood, who instead of breaking down in the subsequent dead rubber in Sydney, breaks down here instead. So, the two teams go to the final Test in Sydney at 2-2 with Larwood either not fit to take the field, or is forced to play under a fitness cloud and breaks down after just a few overs.

If Larwood hadn’t played, England would also be without his 98 as night watchman, and of course Bradman makes a double ton, and Stan McCabe repeats his heroics of the first Test at the same ground, only this time he has a much easier time of it without Larwood.

So, then the only question remains, would Len Hutton have retried the same tactics 22 years later with Frank Tyson and Brian Statham at their peaks? If Australia had gloriously trumped England in 1933 in this alternate history, then they might not have been whinging so much, and bodyline might not have been so hastily banned.

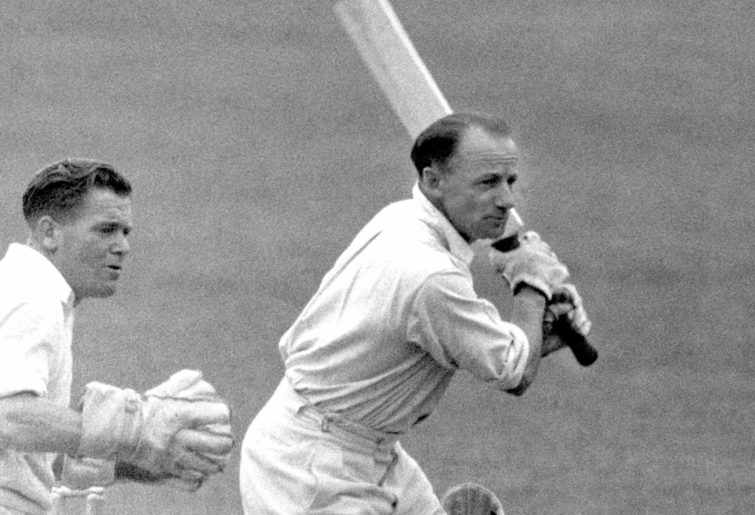

The MCC in Australia. The ‘Bodyline’ tour. Bradman’s first test duck comes in the 2nd test at Melbourne. Clear bowled by Bowes’ first ball. Australia went on to win the match. Mandatory Credit: Allsport Hulton/Archive

2. South Africa do not have their 20-year period of shunned isolation

Just Nuisance can correct me if I’m wrong, but I believe South African domestic cricket jumped right into the limited overs format quicker than all countries other than England.

I know that Graeme Pollock’s 222 was the first ever List A one day double ton – by quite a few years if I’m not mistaken – and I believe it was before 1975. The South African team that had assembled by 1970 were not chokers.

Apart from blowing Australia away in 1971-72, they would also almost certainly have won the inaugural World Cup.

The way the 1975 and 79 World Cups were organised, East Africa would have missed out in 75 and Canada in 79 because of South Africa’s non-isolation. Sri Lanka remain, and still gain Test status in very early 1982.

So, in that inaugural World Cup, nothing changes in the other group, with West Indies still finishing on top, and Australia second. However, South Africa finish on top of their group, England now second rather than first, and New Zealand don’t make the semis.

So now, the match ups are West Indies versus England which the flamboyant calypsos win to still advance to the final. The other semi-final is now between Australia and South Africa.

At Headingly, Gilmour does not run riot, but rather is seen off by Barry Richards after losing his opening partner for only 24 (off 42 balls) – Just Nuisance will have to tell us who Richards’s opening partner would have been, but I am sure he would have been worthy. Was this before Jimmy Cook’s time?

Anyway, Pollock, at first drop rather than second in one day cricket, smashes an unbeaten 164 off only 143 balls, and Richards finishes unbeaten on 146 off 184 balls at the end of 60 overs, South Africa totalling 347 counting extras, which would then stand as an ODI record until the 1987 World Cup when only 50 overs are played, and the West Indies blast 5 for 360 against Sri Lanka.

Pakistan making 5 for 338 at Swansea in 1983 would not be a record, and South Africa would not be in that group because Zimbabwe were in the other group with Australia, India and the West Indies.

Anyway, in response to the Saffie imposing total in that 1975 semi-final, Australia start brightly and Greg Chappell bats well, until, on 65, and just hitting his straps, a very clever fly slip field placement off either Peter Pollock or Mike Proctor brings his undoing. Walters bats well to entertain the crowd, but Australia never look like getting the runs thereafter.

In the final, the West Indies still bat first and Clive Lloyd still bludgeons a century and they still total 291 off their 60 overs. However, in this alternate history, 292 now becomes the highest successful one day chase in history to this point as Richards, 95, once again combines with Graeme Pollock, 87, and Mike Proctor finishes it off with a whirlwind 59 off only 41 balls.

Australia still unleash Lillee and Thomson in the mid-1970s against England and the West Indies, but South Africa dominate world cricket until world series cricket, but the West Indies win the 1979 World Cup. In the second tournament, Canada is not there, so South Africa find themselves in the same group as Australia, England and Pakistan.

South Africa are beaten by Pakistan in that particular group round match and hence finish second to England and then lose the semi-final to first placed West Indies from the other group, and the West Indies, of course are now on the ascendancy post world series cricket. The final between England and the West Indies runs its natural course.

3. Lance Klusener does not have the brain fade in the 1999 World Cup semi-final

This returns to actual history to that point, ignoring alternate history number two above. After smashing the first two balls of the 50th over for 4, to draw scores level, and then conceding a surprising dot ball off the third, Klusener initiates a midwicket conference with Donald, who the Australians could not get at in any way, unless he is out of his crease with the ball in play.

The plan is to only do what they actually did (come sixth and final delivery), if the fourth and fifth balls are dots. Klusener having cleared his head, South Africa get home and play Pakistan in the final, Pakistan of course having triumphed over New Zealand a day or two earlier in the first semi-final.

Now, here’s where it gets interesting … If South Africa wins the final, I win $5,000, no joke, and if Herschell Gibbs makes 121 or more in the final, I win an additional $3000 on account of him being the tournament’s top run scorer … the only batsman anywhere near the run tally 121 in the final takes him to are both long since out of the tournament i.e. Sourav Ganguly and Rahul Dravid …

Alas, this was 1999, and alternate history three is completely independent from alternate history number 2, so there are only two possible outcomes for the final in this alternate history: either South Africa choke in the final, or Pakistan throw the final, and that would have depended on the requirements of the relevant sinister bookies of the time.

I will look at more alternate cricket histories in a day or so, depending on the response to these ones, but if you have any of your own, please feel free to describe them in the comments.