Part 1 listed ten things that will never happen again in an Ashes contest.

Part 2 continues the exercise, with another ten named in reverse order of occurrence. The most recent took place just 30 years ago, while the oldest dates back to 1887.

The WACA, 1990-91

This was the last Ashes match with a rest day. Each subsequent one has been scheduled for five consecutive days. The last in England with a rest day had taken place at the Oval during the preceding series, in 1989.

Rest days used to be social occasions that players eagerly anticipated. They were an opportunity for wine-tasting in South Australia’s Barossa Valley, a cruise on Sydney Harbour, or a round of golf. They took place on Sundays, even when the match had commenced only the preceding day. Nowadays programs are tight, and Sundays are for revenue rather than worship and rest.

(Adrian Murrell / Getty Images)

Arguably the most noteworthy one of all took place during the 1954-55 series’ third match. After two days’ play the home side had reached 8-188 in reply to England’s 191. The pitch was already badly cracking, which didn’t augur well for Australia successfully chasing a fourth-innings target.

However when the teams returned to the ground on the Monday morning, they found that all cracks had mysteriously closed. It was alleged that in the early hours of the rest day, the pitch had been watered. Both the Victorian Cricket Association and the Melbourne Cricket Club denied any such illegal action, claiming that the pitch must simply have sweated under its covers.

The improved pitch ultimately didn’t affect the match’s result. Frank ‘Typhoon’ Tyson took 7-27 to dismiss Australia for 111 in pursuit of its target of 240.

For pedants, the MCG’s subsequent Ashes match of 1994-95 did include a day off. The game commenced on Christmas Eve, paused for Christmas Day, and then resumed on Boxing Day.

The Oval, 1977

This was the last Ashes match in which no batsman wore a helmet. The following year Graham Yallop wore one during a Test in the West Indies, understandably given that he’d suffered a fractured jaw at the hands of Colin Croft when Australia played Guyana.

There are many famous instances of injuries to helmetless batsmen. In Adelaide in 1932-33 during the Bodyline series, Harold Larwood fractured Bert Oldfield’s skull. In the Centenary Test at the MCG in 1976-77, Bob Willis broke Rick McCosker’s jaw.

At the SCG in 1970-71, John Snow struck Graham McKenzie in the face then Terry Jenner in the head. The consequent crowd unrest prompted England skipper Ray Illingworth to lead his team from the field and by doing so risk forfeiting the match.

Helmets have been accused of affecting batsmen’s techniques. They have been blamed for the front-foot press, the playing of hook shots off-balance, and the practice of ducking bouncers rather than moving inside them or swaying out of their line.

Notwithstanding that criticism, helmets haven’t removed all risk from batting. Geoff Lawson used one without a grille at the WACA in 1988-89, and a Curtly Ambrose delivery fractured his jaw. Tragically Phil Hughes paid the ultimate price in a Sheffield Shield match at the SCG in 2014-15. More recently Will Pucovski and Ravindra Jadeja have been concussed.

Old Trafford, 1964

This was the match in which Australian off-spinning all-rounder Tom Veivers returned innings figures of 95.1-36-155-3. Only the West Indies’ Sonny Ramadhin, with 98 overs at Edgbaston in 1957, has bowled more in one innings.

Veivers was one of a number of slow bowlers tried with limited success during the post-Richie Benaud era. In 21 matches he just took 33 wickets at an average of 41.66, with a strike rate of one wicket per 127 deliveries.

Australia led the series 1-0 at the time, and if it did not lose this game it would retain the Ashes. It duly won the toss, batted first and scored 8(dec)656 from 255.5 overs.

Bill Lawry and Bob Simpson added 201 runs for the first wicket. Simpson recorded his first Test century then extended it to 311.

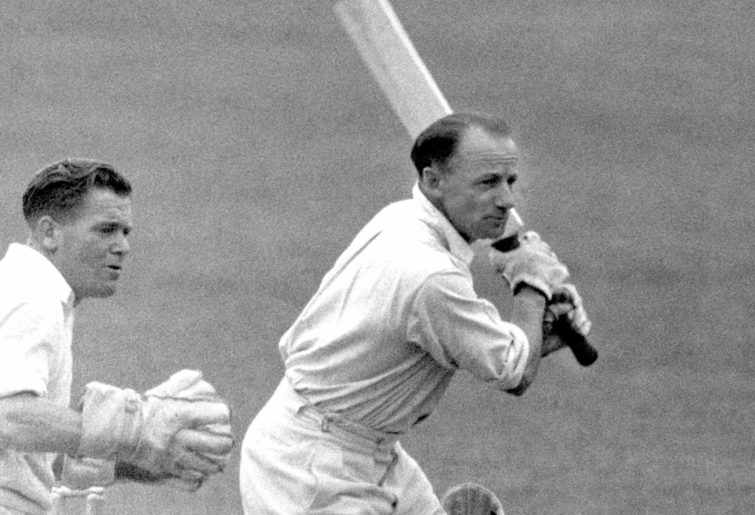

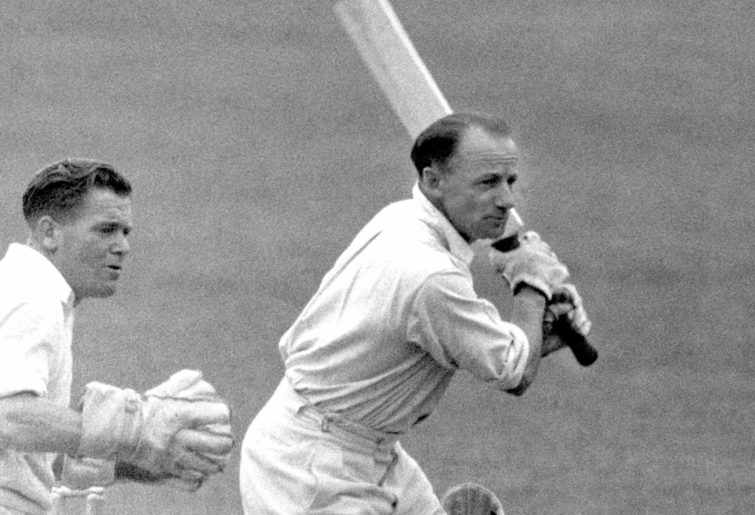

(Photo by Don Morley/Allport/Getty Images/Hulton Archive)

He was on the field for the entire match bar 16 minutes. English debutant Tom Cartwright bowled 77 overs to take 2-118.

With any hope of victory gone, England batted even more slowly to total 611 from 293.1 overs. The innings lasted 15 hours and 14 minutes, during which Australia delivered 19.1 overs per hour.

Ted Dexter and Ken Barrington added 246 runs for the third wicket, scoring 174 and 256 respectively. Graham McKenzie took 7-163 from 60 overs, and Neil Hawke delivered 63 overs to take 0-95.

At today’s over rates, Veivers would have to bowl unchanged for two days and then a further hour to deliver as many balls. Jim Higgs did subsequently bowl the equivalent of 80 six-ball overs in an innings, against England at the SCG in 1978-79.

England tour to Australia, 1954-55

This was the only tour by England to include a match against a country team in every mainland state. Its overall schedule was extremely leisurely by modern standards. A sea voyage was followed by five months in Australia and one month in New Zealand, and then another voyage home. Each Test even comprised six days’ play, with a duration of just five hours daily.

The program included matches against Western Australia Country in Banbury, Queensland Country in Rockhampton, New South Wales Country in Newcastle, South Australia Country in Mount Gambier, and Victoria Country in Yallourn. There were also games against Tasmania and a Prime Minister’s XI. They can’t have done the team much harm, as it retained the Ashes.

Since then the number of such matches has gradually fallen, to the point of them becoming the rare exception rather than the rule. Many factors have increasingly limited visiting sides’ willingness to undertake long tours and play second-class games.

One factor has been increased demands on players during Australian summers. Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka and Zimbabwe have been admitted to Test cricket. India, New Zealand, Pakistan and South Africa have expanded their calendars. Domestic Twenty20 leagues proliferate.

Another has been the increasing commercialisation of the game. No board will ever prioritise a time-consuming up-country match over a broadcast and ticketed white-ball international game. It’s now reached the point where a touring side will prefer a practice session to a minor match.

Trent Bridge, 1938

This was the last Ashes match in which three members of a bowling quartet were specialist wrist spinners. The players in question were Bill O’Reilly, Chuck Fleetwood-Smith and Frank Ward. The trio was supported by paceman Ernie McCormick and all-rounder Stan McCabe.

The selection tactic did not pay off. England’s opening batsmen shared a 219-run first-wicket partnership, and the home side scored 8(dec)658. O’Reilly’s figures were 3-164, Fleetwood-Smith’s 4-153 and those of Ward 0-142. Ward, a former club-mate of Bradman, had gained selection ahead of Clarrie Grimmett for both the tour and the preceding series of 1936-37.

(PA Images via Getty Images)

Fortunately for the visitors McCabe then played a magnificent innings of 232. While his team did not avoid following on, it was able to force a draw after Bill Brown and Don Bradman scored second-innings centuries.

The period was a lean one for faster bowlers in Australia. Between 1935 and 1938 only McCormick was regularly selected. Fortunately in the post-WWII era it could call upon Ray Lindwall, Keith Miller and Bill Johnston.

Australia will never again field a team containing three specialist wrist spinners, anywhere in the world and particularly in England. However in Chattogram in 2017-18, it did defeat Bangladesh by seven wickets with a side that included finger spinners Nathan Lyon, Stephen O’Keefe and Ashton Agar.

The SCG, 1932-33

This was the last match in which a player aged 50 participated. Bert Ironmonger was a left-arm medium-slow bowler who had lost a forefinger in an industrial accident, and spun the ball off its remaining stump. Australian captain Vic Richardson wrote that, “On a wicket that assisted him or a crumbly or wet wicket he was well-nigh unplayable.”

In this match, the last of the Bodyline series, he took 0-64 and 2-34 in an eight-wicket loss. His greatest claim to fame from the game was taking the catch that dismissed England’s nightwatchman Harold Larwood for 98. Given that Ironmonger was a poor fieldsman who took only three catches in his entire Test career, Larwood was desperately unlucky to not achieve a century.

Ironmonger was nicknamed ‘Dainty’ due to his awkwardness in the field and with the bat. Questions over his bowling action contributed to his non-selection for the Ashes tour of 1930. Having made his first-class debut in 1909-10 aged 27, he continued for a further 26 years until 1935-36 and the age of 53.

He was the leading bowler in both the Sheffield Shield and the Melbourne club competition in 1914-15. From that time, he always understated his age by four years. However he did not gain a permanent place in the Victorian team until 1927-28 by which time he was aged 45.

Ironmonger then debuted for Australia against England in 1928-29 at the age of 46. In 14 matches he took 74 wickets at an average of 17.97. His best match figures were 11-24 against South Africa at the MCG in 1931-32, and 11-79 against the West Indies at the same ground in 1930-31.

The MCG, 1928-29

This was the only Ashes match that lasted eight days. In ideal batting conditions it was to be played to a result, with a rest day after the match’s second day, and each day’s duration only five hours. An earlier game in the series had lasted seven days. From 1882-83 until 1936-37, every match in Australia was a timeless one.

The visitors scored 519 and 257, to which Australia replied with 491 and 5-287 to win by five wickets. The two sides delivered 707.2 overs at an average over rate of almost 21 overs per hour. By comparison, currently a Test is scheduled to last just 450 overs.

Highlights included centuries to Australia’s Bill Woodfull and Don Bradman, and England’s Jack Hobbs and Maurice Leyland. Woodfull faced 381 deliveries during his innings of 102 which included only three boundaries.

(Photo by S&G/PA Images via Getty Images)

The second day’s play yielded 186 runs from 101.1 overs, the fifth 142 runs from 86.3 overs, and the seventh 166 runs from 94 overs. The match’s first two innings lasted almost five days in total.

After the match, the English team made a four-day rail journey to Perth where it played a game against an Australian XI. It then embarked on a four-week journey home first by sea, then by rail overland across France, then by sea again.

It’s easy to understand why players, broadcasters and administrators have abandoned match and tour arrangements such as these.

Old Trafford, 1921

This was the last Ashes match in which a bowler delivered two consecutive overs. The player in question was Australian captain and anti-administrator Warwick Armstrong.

The occasion was the second day’s play of the series’ fourth Test. England chose to bat first and the Wisden Almanack described neatly what happened next:

“An unfortunate and rather lamentable incident occurred during the afternoon. At ten minutes to six, with the total at 341, Tennyson came out on to the field and declared the innings closed, being quite forgetful of the fact that under Law 55, as amended by the MCC in 1914, he had no power to do so.

“The first day having been a blank, the fixture became a two day match and the declaration could not be made later than an hour and forty minutes before time, so Tennyson was just an hour too late. It was strange that no one in the pavilion remembered the existing law sufficiently well to save him such a blunder. Armstrong signalled to his men to remain on the field, but eventually they as well as the umpires followed Tyldesley and Fender to the pavilion.

“A little argument soon put the matter right, play continuing after an interval of a little more than twenty minutes. The general confusion led to another breach of the laws, for on a fresh start being made Armstrong, who had bowled the last over, sent down the next.”

Interestingly, this would not be the last such incident. When England played in Wellington in 1950-51, the home team’s leg spinner Alex Moir delivered the over immediately before the tea interval on the match’s last day, and subsequently also the first over after the interval.

Even more interestingly, until 1889 it was in fact legal to bowl two consecutive overs in a match. At the time, the laws of cricket stated that, “The bowler may not change ends more than twice in the same innings, nor bowl more than two overs in succession”.

Statistician and historian Charles Davis has established that the practice occurred “at least two dozen times”. Most notably, Australia’s Fred Spofforth did so in each innings at the Oval in 1882, when the visitors’ seven-run victory prompted the creation of the Ashes.

Old Trafford, 1896

This was the match that yielded a record-breaking number of runs and overs in the three days available, and two legendary English players’ finest performances. The series heralded the beginning of the golden age of cricket.

The days witnessed 366, 386 and 321 runs respectively. The average over rate was equivalent to almost 22 six-ball ones per hour, by comparison with today’s 13 to 14. No modern match features such outputs of activity.

Australia scored 412 then dismissed the home side for 231 and enforced the follow-on. England improved to total 305 in its second innings. The visitors’ victory target was 125, which they achieved for the loss of seven wickets.

Tom Richardson was England’s hero. In Australia’s first innings he delivered 68 of the 170 five-ball overs bowled, to take 7-168. During the first day’s play, he bowled the equivalent of more than 50 six-ball overs.

In the last-day run chase he then bowled unchanged for more than three hours. Of that innings’ 84.3 overs, he delivered all 42.3 from one end, and almost inspired a remarkable come-from-behind victory as Australia slumped to 7-100 with 25 runs still needed.

(Photo by Ryan Pierse/Getty Images)

He is one of England’s greatest cricketers. In a 14-match career he took 88 wickets at an average of 25.22. That tally included 11 five-wicket hauls and ten wickets in a match four times. In the preceding Test he had taken 6-39 and 5-134 to spearhead a win.

When Neville Cardus named his six greatest cricketers for the Wisden Almanack’s centenary in 1963, Richardson was among them. The others were WG Grace, Victor Trumper, SF Barnes, Jack Hobbs and Don Bradman.

Teammate Kumar Shri Ranjitsinhji had waited seven years to qualify to play for England. The conservative Marylebone Cricket Club then declined to select him for the preceding Lord’s match on the basis of his colour.

The Lancashire County Cricket Club had no such qualms. ‘Ranji” agreed to play as long as the Australians did not object, and as long as the selection committee’s decision had been unanimous.

In his team’s first innings he batted cautiously to score 62 as the side conceded a 181-run deficit. When the team followed on he scored a brilliant and chanceless 154 not out in 185 minutes, with 23 boundaries.

He is another of his country’s greatest players. In 15 matches he scored 989 runs at an average of 44.95, with two centuries and six fifties. In all first-class cricket he amassed 24,692 runs at 56.37 including 72 hundreds. He is credited with perfecting the leg glance, late cut and back-foot defence.

The SCG, 1886-87

This was an Ashes match with three unique or extremely rare instances. Firstly, it was the last Test match for the only cricketer that played both for and against each side. Secondly, it was the last time that a team member acted as an umpire during the match. And finally, a player in it took a crucial catch while acting as a substitute fieldsman for the opposing side.

England-born Billy Midwinter represented Australia in what are now recognised as Test cricket’s first two games, in 1876-77. For the four-match series of 1881-82 he switched sides to England. In 1882-83 when the Ashes were contested for the first time, he returned to the Australian side. When the teams met again in 1884 and 1886-87, he played a further five times for Australia.

Midwinter played a total of 12 matches across five different series. The inaugural Test match proved to be his career highlight, with figures of 5-78 and 1-23 crucial to a 45-run victory. This game ten years later, his last, was a forgettable one with just one wicket and scores of one and four.

England batsman William Gunn deputised for umpire John Swift on the match’s fourth day, due to Swift’s unavailability. Gunn had scored nine and ten earlier in the match, and the visitors did not need him as a bowler when Australia batted. The home side resumed its innings at 5-101 in pursuit of 222 for victory, and was dismissed for 150.

Perhaps Gunn had to adjudicate on a few appeals by his teammates, given that the five wickets to fall included two catches by the wicketkeeper as well as a run-out. Subsequently England would bring a qualified umpire with it on each of its tours, who could officiate with a local one in each match.

Great Australian bowler Charlie Turner was the player to field for England. After being dismissed with his team’s score on 121, he returned to the field and only eight runs later caught out teammate Reginald Allen. It’s reasonable to assume that Turner was only acting as a substitute fieldsman for England, because Gunn was umpiring at the time.

The day’s events indicate a lot about cricket’s administration and conventions of the period. It’s amusing to imagine a current player taking part in any of them.

Watch out for Part 3 next week, with a final ten stories from the Ashes archives.