This article completes this series, with a final ten instances.

The previous Part 1 and Part 2 listed 20 other things that will never happen again in an Ashes contest.

Perhaps in 50 years’ time cricket followers will look back and marvel that it was once played for five consecutive days, in daylight hours, on natural turf, with a red leather ball, between teams of 11 players wearing white, in five-game series.

England tour to Australia, 1979-80

This is the only series in which the Ashes trophy was not awarded to the winning side. It’s also the only stand-alone series since 1896 that comprised just three matches, and the sole instance of series hosted in consecutive summers.

1979-80 was the first Australian season following World Series Cricket. By then both Kerry Packer and the Australian Cricket Board conceded that an ongoing dispute would be in neither party’s interest. Negotiated outcomes included broadcast rights for Channel Nine, WSC players’ eligibility for Australian and state sides, and a hastily-rearranged program that required an India tour’s postponement.

England agreed to a short series, but refused to contest the Ashes given that 12 months prior it had retained the trophy by a 5-1 margin. Its team included WSC player Derek Underwood.

(Photo by S&G/PA Images via Getty Images)

The West Indies agreed to a short series similarly, and also participated in Australia’s first one-day tournament. The overall program was haphazard. The host played alternating Tests against each opponent, and blocks of one-day matches between games.

England’s refusal proved to be wise. Although the home side won each match by a comfortable margin, it would not reclaim the trophy until 1982-83.

Other parties continue to promote a World Test Championship in which each nation would play three-match series home-and-away against each opponent. However tradition and commercial interests make Ashes series in that format extremely unlikely.

Headingley, 1975

This is the only match to have been abandoned due to vandalism. The pitch was sabotaged with both the series and the game delicately poised.

It was the third match of a four-game series which Australia was leading 1-0. England scored 288 then dismissed the visitors for just 135. A further 291 by the home side created a daunting 445-run lead. The odds favoured a series-levelling England win and a six-day decider at the Oval.

By stumps on the match’s fourth day, Australia had reached 3-220 and required a further 225 runs. Rick McCosker and Doug Walters were undefeated on 95 and 25 respectively.

Unfortunately when ground staff removed the covers the following morning they found that overnight, holes had been dug in the pitch just short of a length, and then engine oil poured into them. The lone security guard had seen and heard nothing.

Both captains agreed that conditions were unplayable, and the game was declared a draw. Australia therefore retained the Ashes with one match still to play.

As it turned out the match would probably have been drawn anyway, because rain fell from lunchtime onwards. McCosker did score his maiden century on the following Test’s first day. Walters lost a rare opportunity to play a match-winning innings in England.

Campaigners for the release of convicted robber George Davis claimed responsibility for the damage. His brother was jailed for 18 months for the act. Davis was later freed from his 20-year sentence, only to be jailed again after re-offending, and then for a third time for yet another crime.

Such lack of security will never recur. Security teams, floodlights, fences, alarms and full-square pitch covers now ensure that an event as lucrative as an Ashes match cannot be prevented from taking place.

The Gabba, 1958-59

This is the match that featured the slowest individual half-century of all time. The batsman responsible was the aptly-nicknamed England all-rounder Trevor ‘Barnacle’ Bailey.

The game was the first of an eagerly-anticipated series. England was arguably the strongest team in world cricket, and had won each of the three preceding Ashes series. The home side was on the rise, and Richie Benaud was leading it for the very first time.

(Photo by Ryan Pierse/Getty Images)

England laboured to 134 from 59.4 eight-ball overs, equivalent to a scoring rate of just 1.68 runs per six-ball over. Australia replied with 186 at a speed that was only marginally quicker.

When the visitors batted again, Bailey was promoted to number three. He responded with an innings of 68 that was even slower. It took him 458 minutes and 427 deliveries. He reached his half-century in 357 minutes from 350 balls. His innings contained just four boundaries.

None of Bailey’s top-order teammates scored significantly faster than him. As a result their side made only 198 at a scoring rate equivalent to 1.24 runs per six-ball over. England was able to set the home side just 147 for victory which it reached for the loss of two wickets.

Unfortunately the series failed to live up to the hype, at least in terms of attractiveness of style. Not only were scoring rates generally low, but each match day featured only five hours of play.

The game’s first four days yielded only 142, 148, 122 and 106 runs in turn. It should come as no surprise that Bailey batted for the entire fourth day, scoring just 41 of those 106 runs made from the equivalent of 92 six-ball overs.

Such scoring rates are unthinkable today, even in rear-guard attempts to draw with no prospect of victory. Contemporary techniques, tactics and power-bats will always ensure that any player good enough to bat for a day or longer will always score at least 100 runs in the process.

The Oval, 1938

This is the last timeless Ashes match. It saw one team make a record score, one batsman do likewise, and one bowler concede a record number of runs.

Australia led the series 1-0 after two games had been drawn, and the match at Old Trafford washed out without a ball bowled. With its outcome still undecided, the last game was to be played to a result. Ironically it lasted only four days.

England batted for 335.2 overs and almost three days to score 7(dec)-903. It declared shortly after Don Bradman was carried from the field injured. That total stood as a record until Sri Lanka’s 6(dec)952 against India in Colombo in 1997.

Len Hutton scored 364 after surviving a straightforward stumping chance on 40, and being caught from a no-ball when on 153. Arthur Wood replaced him at the crease with the score 6-770 and the comment, “Aye, I’m just man for crisis”. That record has subsequently been broken first by Garry Sobers and then by Brian Lara, Matthew Hayden and Lara again.

(Photo by S&G/PA Images via Getty Images)

Left-arm wrist spinner Chuck Fleetwood-Smith bowled 87 overs to take 1-298, still the most runs ever conceded in a single innings. Three bowlers have subsequently delivered more balls in one innings, but none of them were as expensive.

Australia made its replies of 201 and 123 with only nine batsmen, following injuries to Bradman and Jack Fingleton. The visitors lost the match by an innings and 579 runs.

A few months later Durban hosted the last ever timeless match. It ended in a draw after ten days’ play and two rest days. The England team had to return home on the last available passenger liner, despite its score being 5-654 and only 42 runs short of a 696-run victory target.

Cricket will never again experience a timeless Test. Some administrators are now lobbying for four-day ones, with a few such games having taken place recently.

Lord’s, 1930

This is the match in which one side scored 800 runs yet lost. In just four days the game yielded 1601 runs from 505.4 overs.

By the end of the first day England had scored 9-405 from 123 overs, with KS Duleepsinhji having made a magnificent 173. The home side was well-placed, or so it appeared at the time.

24 hours later, Australia went to stumps at 2-404. The second day’s play had produced a total of 424 runs from 134.4 overs. Don Bradman, playing a Test at the home of cricket for the first time, was undefeated on 155.

On the third and penultimate day Australia continued batting at the same rate, and England bowling its overs just as quickly. Bradman extended his score to 254, an innings he considered the finest he ever played.

The visitors eventually declared at 6-729, to which the home side replied with 2-98 by stumps. During another eventful day, 141 overs yielded 423 runs for the loss of six wickets.

Australia won the match late on the fourth and last afternoon, but not without a scare. England reached 375 in its second innings for an overall lead of 71, thanks to skipper Percy Chapman’s swashbuckling 121. The visitors then slipped to 3-22 with Bradman’s wicket one of those to fall. It reached its target without further loss, after a day that provided 349 runs and 11 wickets from 107 overs.

Matches like these certainly ensured that spectators in the 1930s got value for money. Nowadays four days of Test cricket will yield at most two thirds this number of overs, and three quarters this number of runs, despite up to 30 additional minutes of playing time being added to each day.

(Photo by S&G/PA Images via Getty Images)

Adelaide Oval, 1928-29

This is the match in which one player bowled 124.5 overs to take 13 wickets and deliver a 12-run victory on the seventh day of a timeless Test. The win also gave the away side a 4-0 series lead.

The player was England’s left-arm orthodox slow bowler JC ‘Farmer’ White. Great stamina aside, his strengths were accuracy, flight and changes of pace.

The match was evenly-contested throughout. England batted first and scored 334 with Wally Hammond’s share an undefeated 119 and Clarrie Grimmett taking 5-102. Australia responded with 369 thanks to debutant Archie Jackson’s sublime 164.

The visitors then added a further 383 as Hammond continued his brilliant series with a marathon 177 from 603 balls. The home side ultimately fell just short of its 349-run victory target.

In Australia’s first innings which lasted 160 overs, White’s figures were 60-16-130-5. All five of his victims were top-eight batsmen including Jackson, Alan Kippax and captain Jack Ryder.

In Australia’s run chase, which lasted 151.5 overs, White’s figures were 64.5-21-126-8. The home side had been well-placed when it needed just 41 runs to win with four wickets in hand. However Jack Hobbs ran out Bradman, and White took the other three wickets as England got home with 12 runs to spare.

White’s total match figures were 124.5-37-256-13. He bowled 40 per cent of his side’s overs, and took all but six of the 19 wickets that fell to bowlers.

The number of overs bowled by White has been exceeded only twice, each time by a few balls in a drawn game. England’s Hedley Verity did so in Durban’s timeless Test in 1938-39, and the West Indies’ Sonny Ramadhin at Edgbaston in 1957.

Such figures will never be approached again, due to time-limited matches and lower over rates. However just a few months ago Afghanistan’s Rashid Khan did manage to deliver 99.2 overs against Zimbabwe in Abu Dhabi.

A visiting team will probably never again take a 4-0 lead in a series, either. The current lack of warm-up matches in either country prevents any side from acclimatising and finding form before commencing a Test series.

The Oval, 1926

This is the match in which a team selector was recalled aged 48 after a five-year absence, and delivered an Ashes-winning performance. The player was legendary English all-rounder Wilfred Rhodes.

He had debuted as a spin bowler 27 years previously, so long before that WG Grace was a teammate and Victor Trumper an opponent. Between 1909 and 1921 he instead was a specialist opening batsman.

England had not defeated its opponent in any of their preceding 19 matches. Australia had won 5-0 in 1920-21, then 3-0 in 1921 and most recently 4-1 in 1924-25.

The 1926 series was level at 0-0 after four games, thanks to wet weather and the three-day match format. With the series still alive and the final Test to be a timeless one, the home side’s selectors took a risk.

(Photo by Ryan Pierse/Getty Images)

They persuaded Rhodes to make a comeback in his original role of bowler, rather than his subsequent one of batsman. This despite him having taken only 17 wickets in his 28 games since 1909, and not having represented England at all since 1921.

England’s gamble paid off handsomely. He returned figures of 25-15-35-2 and 20-9-44-4. England won the match by 289 runs, and so recovered the Ashes.

All six of his wickets were of recognised batsmen. As well as clean-bowling ‘The Unbowlable’ Bill Woodfull he dismissed Bill Ponsford, Warren Bardsley and Herbie Collins, and Arthur Richardson twice.

Rhodes later played one last series in the West Indies in 1928-29 when England toured there and New Zealand simultaneously. He was aged 52 at the time.

Selector and opening batsman Cyril Washbrook enjoyed a similar experience in 1956. After five years’ absence he was recalled at the age of 41 to play against Australia at Headingley, and scored 98 in a memorable win.

Despite Australia’s occasional struggles during the past decade, it’s most unlikely that selectors Trevor Hohns, Mark Waugh and George Bailey ever seriously considered a return to the field of play.

The Oval, 1909

This is the match in which the most prolific wicket-taker of all time commenced his second career as a successful opening batsman. The player was Wilfred Rhodes, the left-arm finger spinner whose career tally of 4204 first-class wickets will never be broken.

Rhodes made his debut at Trent Bridge in 1899. He opened the bowling in each innings, taking 4-58 and 3-60. Batting at number ten, he scored a modest six runs.

The then specialist bowler played the first of many famous innings, albeit a brief one, at the Oval in 1902. Batting at number 11, he and George Hirst scored the 15 runs required for a thrilling one-wicket victory. Hirst’s apocryphal welcome to Rhodes was: “We’ll get ‘em in singles”. More expectedly he also took 7-17 at Edgbaston, 5-63 at Bramall Lane, and 4-104 and 3-26 at Old Trafford.

Rhodes then gradually worked his way up the order, until in the 1909 series’ final game he scored 66 at number three followed by 54 opening the innings. He then established a highly-successful combination with Jack Hobbs, England’s finest ever batsman.

The pair opened together 36 times between 1910 and 1921, and those partnerships yielded 2146 runs with an average stand of 61.31. Eight of their stands exceeded 100 runs. They included partnerships of 323 and 147 in Australia in 1911-12, and 221 and 159 in South Africa in 1909-10.

Of all opening pairs to have batted together more than 27 times, only Hobbs and Rhodes’ successor Herbert Sutcliffe has a higher average partnership.

As Rhodes’ batting assumed more and more importance, he bowled less and less often. However he never lost his skills with the ball, as shown by his performance at the Oval in 1926.

It’s impossible to envisage any modern player successfully transitioning from Test-level specialist bowler to Test-level opening batsman, let alone doing so over a 30-year period.

Bramall Lane, 1902

This is the only Test match that took place at the ground. Australia therefore has a permanent undefeated record there, after winning the game by 143 runs.

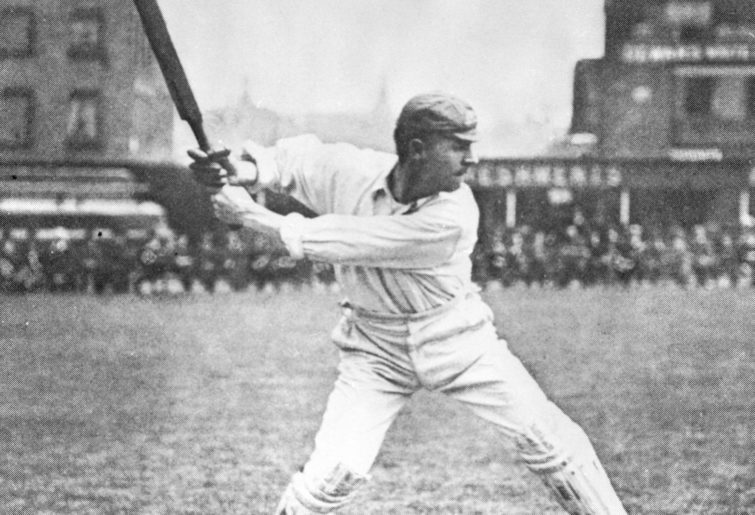

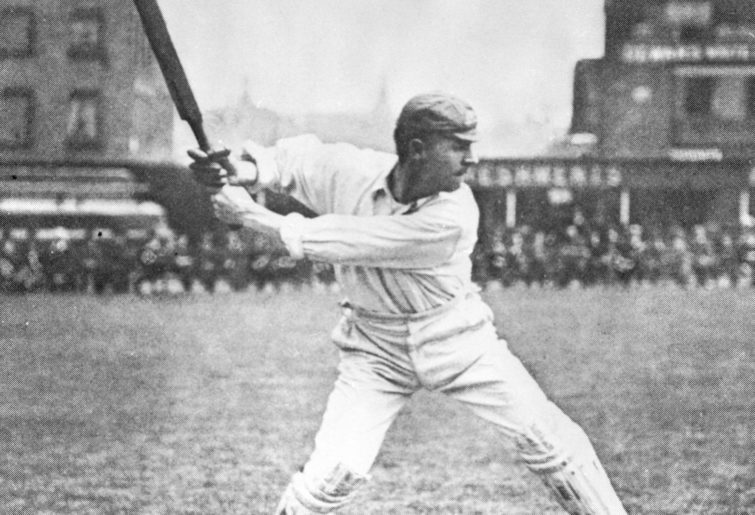

Clem Hill scored a superb 119 from 130 balls, and Victor Trumper 62 from 65 deliveries. Monty Noble took 5-51 and 6-52, and added a valuable 47 with the bat.

(Photo by Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

Reportedly the ground’s greatest shortcoming was the quality of its natural light. It was surrounded by factories, whose smoke could make sighting the ball difficult and from time to time halted play. The lack of a sight screen in front of the members’ pavilion exacerbated the problem.

The game was the third in one of the most exciting series ever played. Australia won it by a 2-1 margin in a wet summer that regularly made pitches unplayable for all but the greatest of batsmen.

The year following the game, Yorkshire County Cricket Club relocated its headquarters to Headingley in Leeds. Bramall Lane was also the home ground of Sheffield United Football Club, and hosted its last cricket match in 1973.

The SCG, 1882-83

This is the only match to have been played on four separate pitches. In addition, while it was the last game in a four-Test tour, its result did not count towards the Ashes trophy created just weeks earlier.

In August 1882 at the Oval, Australia had won a one-off match by just seven runs. The result prompted the famous obituary in The Sporting Times lamenting the death of English cricket. The announcement stated that the body would be cremated and its ashes taken to Australia.

England claimed the subsequent three-match series in Australia by a 2-1 margin. Some local women then burned a bail, sealed its ashes in an urn, and presented it to winning captain the Hon Ivo Bligh.

It was then agreed to play this additional game, and to give each captain the choice of a fresh pitch for each of the match’s four innings. The preceding game at the SCG had featured two pitches, one for each side.

The match was relatively high-scoring. England scored 263 and 197 on its pair of pitches. Home skipper Jack Blackham chose his side’s two wisely, and for good measure recorded personal scores of 57 and 58 not out. Australia replied with 262 and 6-199 to win by four wickets. However as agreed, the visitors retained the inaugural Ashes trophy even though Australia had in some eyes levelled the series 2-2.

Such playing conditions say much about pitch quality and batting challenges during the late 1800s. As does the fact that until 1893, the follow-on was compulsory for any team with a deficit of just 80 runs.

Given the era’s bowler-friendly conditions, it is surprising that this series was the one that introduced timeless Tests. They would continue in Australia and South Africa until WWII, and in England under certain circumstances.