First, it was COVID-19. Now, it is COP26. Neither a worldwide pandemic, nor a global conference on the planet’s future have been able to slake the thirst of the so-called ‘developed’ nations for fossil fuels.

The Earth is still a long way from turning green. Burnt umber is a far more likely colour for the future landscape we will all have to inhabit.

In the far smaller biosphere of rugby, Ireland have quietly been creating their own brand of green energy, one which resulted in their third win in the last five matches over the All Blacks on Saturday afternoon at the Aviva stadium in Dublin.

While New Zealand supporters may argue that the All Blacks won the one that really mattered – the 2019 World Cup quarter-final in Chōfu – it is still a record of which the other home nations, and more recently Australia, will be envious. Wales have been waiting for the last 68 years for even the slightest whiff of a victory.

Behind the scenes, Andy Farrell and his backroom staff have been busy transforming the true blue of Leinster into the evergreen of Ireland. There were no less than 12 starters from the Dublin province featuring in the teams which Faz and Co. sent out to play Japan and New Zealand over the past fortnight. If there is a provincial side anywhere in the world equipped to play international football, it is Leinster.

What does ‘green energy’ really mean in rugby? It means keeping the ball whenever possible and not giving it away for free. It means husbanding your resources and wringing out every drop of potential for constructive work on attack with ball in hand.

It is a lesson the great Australian teams of the Rod Macqueen era in the early noughties had learned deeply, all the way down to their bootstraps. You keep the ball, you wear down the defence and you probe patiently, waiting for the gaps to appear.

Let’s take a deep dive into the stats comparing the performances of those two traditional possession-based powerhouses this autumn – Ireland and Australia. Over the two games so far:

• Ball-in-play time averages over 35 minutes for Ireland, but only 30 minutes for the Wallabies

• Ireland average 153 ball-carries for a massive total of 879 metres per game; for Australia read 66 carries for 430 metres

• Ireland win 68 per cent of their ruck ball at lightning-quick (0-3 second) speed, at a 95 per cent retention rate; for Australia, that percentile drops to 49 per cent at 92 per cent.

• Ireland average 38 passes by their forwards, the Wallabies only 22 passes per game.

Ireland have enjoyed 62 per cent domination of possession and 67 per cent territory, and an average of 22 minutes of attack over their two games; for Australia read 44 per cent possession, 46 per cent territory and just over 13 minutes spent on attack.

So how do the Wallabies regain their true birth-right in the professional era, and become one of the ball-control giants of the global game? The way Ireland went about their business in the win over the All Blacks gives more than a few important clues.

Leinster insist that all of their forwards are able to handle the ball, pass it and make decisions about how to use it. They require that all their players are able to make those decisions close to the gain-line, in the teeth of defensive pressure. They also require huge work rate on (same-way) attack across the whole width of the field, with a demand that ball-carriers always have multiple options at their disposal on every phase of attack.

If you can do all of that consistently, you can force defences to work harder for longer, and place them under stress. Ireland’s opponents have had to make an average of over 200 tackles per game, Australia’s only 80.

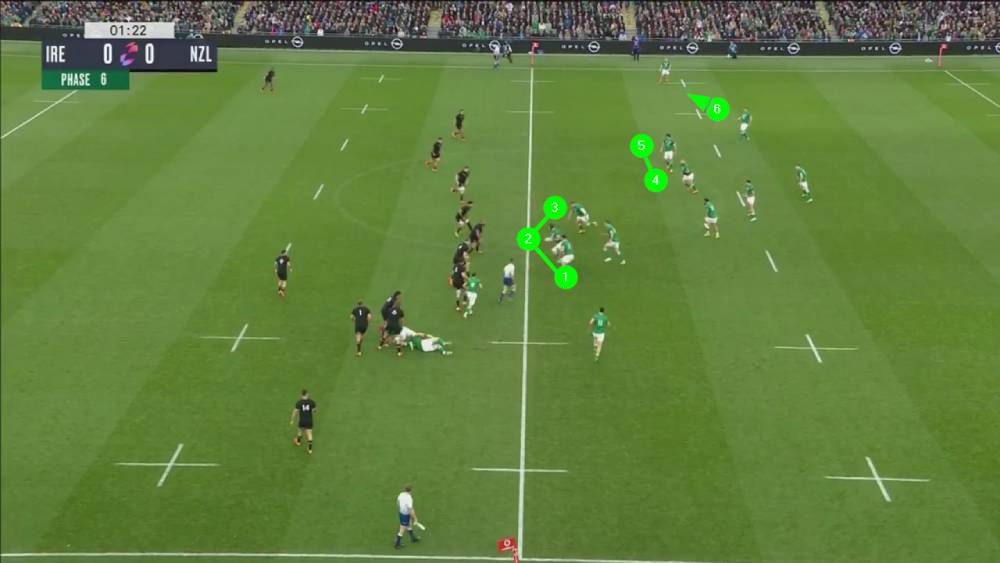

Let’s take a look at some instructive passages of play from the game in Dublin. Where Australia have only managed one sequence of seven-plus phases in their two tour games so far, Ireland put together eight sequences against the All Blacks alone. The men in green were unafraid to play out of their own exit zone:

The handling and decision-making are all being made by Irish forwards in this sequence. First hooker Ronan Kelleher picks the intercept off his laces, then loose-head prop Andrew Porter and second row Iain Henderson decide between them on the timing of play at the base of the ruck. Finally, number 8 Jack Conan is unafraid to make the extra transfer to the man outside him when he sees James Ryan in a better position to make yardage.

Penalty Ireland.

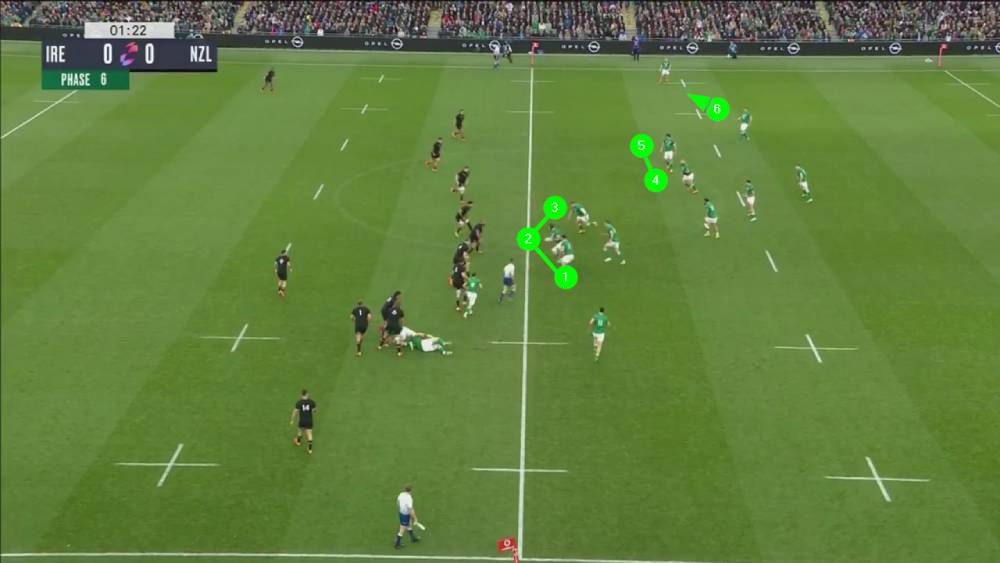

The men in green were able to maintain impressive attacking shape as they played out from their own 22m line:

That was after eight phases had been constructed, and 18 passes made. Both the structure and the connectivity between forwards and back is close to the ideal:

Only one player is consumed in the ruck, there are six forwards interacting with four backs to the wide of the field, and Johnny Sexton is playing as close to the forward pod in front of him as humanly possible.

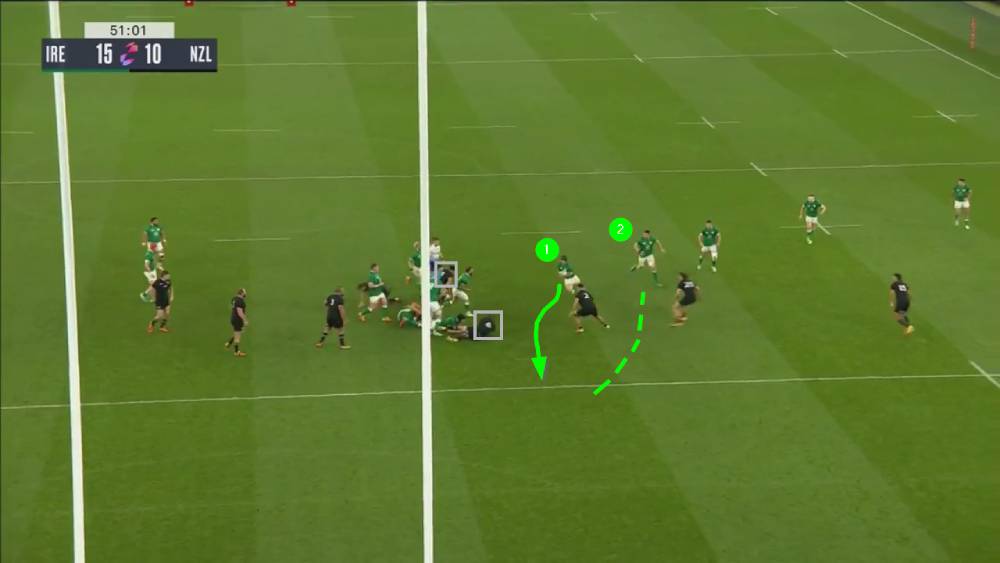

The view from behind the posts reveals further subtleties:

The first ball-carrier (number 6 Caelan Doris in the black hat) ensures that he swerves towards the inside shoulder of the defender in front of him before delivering the ball out the back to Sexton, and all of the attackers outside the veteran Ireland number 10 draw their men before unloading. The second pod of forwards are real threats to receive the ball before it is ever moved wide, so the overlap play succeeds.

Leinster demand immense work rate from all their attackers, and left wing James Lowe spent an indecent amount of time on the ‘wrong’ side of the field:

Those kind of intrusions into the line going towards the right side-line are positively Marika Koroibete-like.

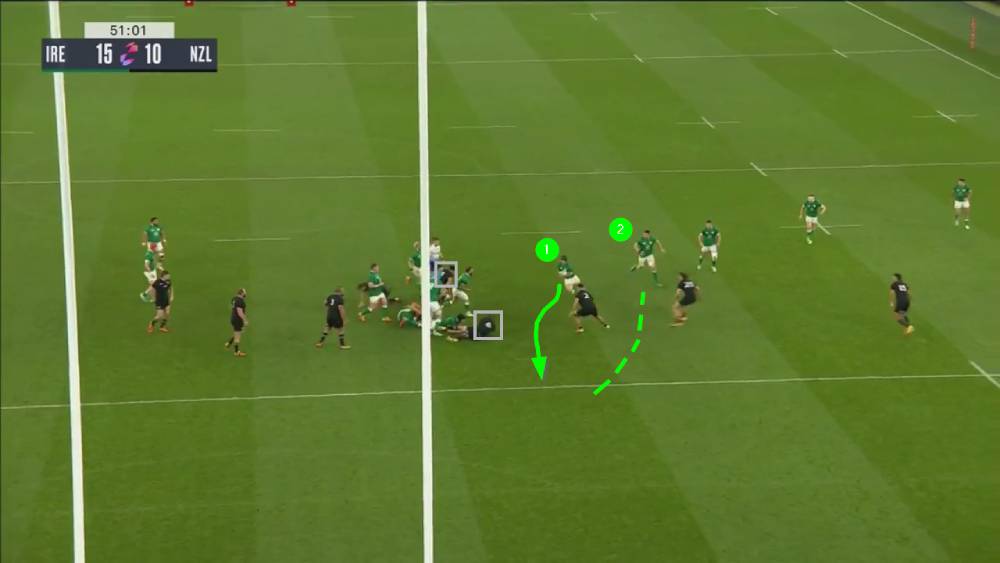

Lowe was a major influence in the right half of the field during the build-up to Ireland’s second try of the game:

Twice the Ireland left-wing handles the ball in the approach work, and Kelleher finished the job two phases later.

Lowe has even learned how to pass and release the man outside him during his stint with Leinster!

Lowe fires a bullet right down the middle of the tunnel between two All Black defenders to unleash Jack Conan on a gallop, and he’s still there in support when his Leinster team-mate is finally brought to a halt by Akira Ioane.

The work rate of the Leinster forwards in attack was truly awe-inspiring:

Look at the men who are contributing to the ball-winning in the first instance: Kelleher is throwing a lineout ball to Doris, with Conan also stationed in the front half of the line.

Kelleher has already wrapped around to make a powerful carry on second phase, while Doris and Conan have beaten their opposites (Ardie Savea and Ethan Blackadder) around the far corner on the scoring play:

Blackadder has been taken down in the cleanout, and Ardie cannot get across in time to stop Doris penetrating through the hole on Codie Taylor’s inside shoulder.

The ability of Ireland’s forward to multi-task in the manner we usually associate with the All Blacks themselves was one of the major takeaways from the game:

On the way out, we have Doris and Tadhg Furlong (who also had an outstanding game) functioning without any problem as midfield passers and unlocking the wide space on the far side. Furlong then attends the first ruck, before becoming a ball-carrying option, along with the Ireland number 6 on the way back home:

Once again, the ball is made available immediately at the ruck and the attack can continue without any loss of momentum.

Summary

The number of occasions you can say that a New Zealand forward pack has been beaten at the multiple tasks of both ball-winning and ball-using can be counted on the fingers of one hand, but that is what happened at the Aviva stadium.

On the evidence of the match in Dublin, only two or three of the New Zealand forwards would make it into the Irish pack, and the same doubts with which Ian Foster and his coaches entered the game remained at the end.

Will Brodie Retallick and Sam Whitelock make it to the 2023 World Cup, and who are their replacements if they don’t? Is the right balance in the back-row and midfield any closer to discovery? Who is the best back-up to Aaron Smith at number 9, and who should start in the halves outside him? These questions are all still alive and well.

The Wallabies will meanwhile be looking at Ireland’s ability to control their own ball, and move upfield slickly with ball in hand with a mix of envy and admiration. Australia (under Rod Macqueen) and Ireland (under Joe Schmidt) were always the flag-bearers for ball-control sides in the professional era. But if you are only building an average of 46 rucks per game (as the Wallabies currently are on tour), you are not going to create too many opportunities or score too many tries.

Historically, the best Australian teams have applied pressure on their opponents by keeping the ball and forcing them to tackle themselves to exhaustion. That’s where the Wallabies can find their ‘green energy’.

With the likes of Quade Cooper, Samu Kerevi, Marika Koroibete and Reece Hodge coming back into the equation in the backs, and Allan Alaalatoa, Taniela Tupou, Brandon Paenga-Amosa up front, there is hope.

But on the evidence of the tour so far, the hole that lies just below the top crust of blue-chippers is gloomier than an abandoned coal mine.