Ahead of the 2022 NRL season, the only major alteration to the rules was a tweak to the six-again, restoring penalties for infringements within 40 metres of the ball-handling team’s own tryline, and bringing NRL rules closer to those of the UK Super League.

This rule adjustment comes from the ingenuity of coaches to exploit the deficiencies of the six-again rule, which was introduced two years ago.

I had predicted the introduction of the six-again to replace penalties from within ten metres for some time before its introduction to the NRL and should have written about it then.

Instead, I held off for more data, which has been pivotal in my analysis but has perhaps prevented me from gaining the status of rugby league clairvoyant.

If I’d published then, I might have been called a mind-reader, as was the case when colleagues contacted me after years of listening to my whinging about the old rules governing mutual infringement before the spectacular, avoidable blunder we saw in the Roosters’ win over Canberra in the 2019 grand final.

But having decided to wait, I’m content to provide the origins and analysis.

Looking back, the purpose of the six-again was to reduce interruptions in play and ‘speed up’ the game.

While I reserve the right to be pedantic and say that this actually doesn’t speed up the game in a literal sense, as nobody is running any faster nor is the game less than the regulation time limit, it does certainly maintain a greater amount of uninterrupted movement and fluidity of the ball in motion within the 80 minutes.

I have refereed both rugby league and touch rugby league (TRL), and it was there that I was introduced to the concept of a six-again-like rule from within eight metres. Here, when coming from the touch (would-be ruck), a player must retreat to the eight-metre line but may do so in any straight line.

If the player wants to do so diagonally, that’s fine so long as they hold their line and/or stay out of play.

If the player does not, then a zero tackle is awarded on the fly without stopping play, in the same method we now award the six again, a ‘seven again’ if you would.

But that got me wondering where this strange rule came from.

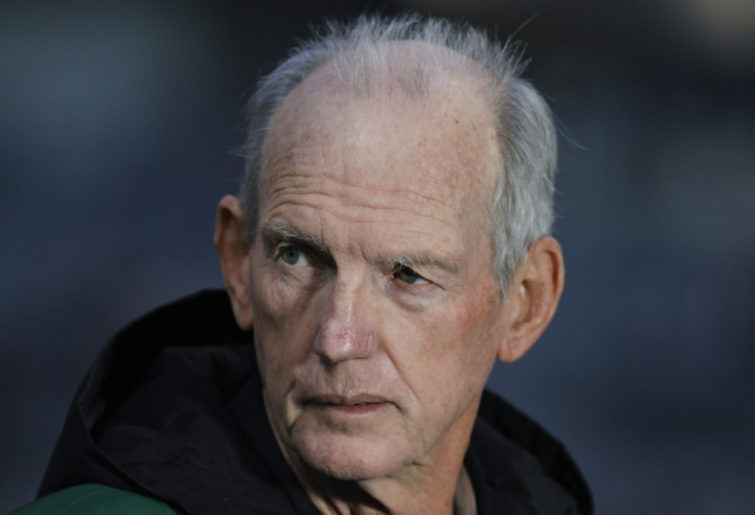

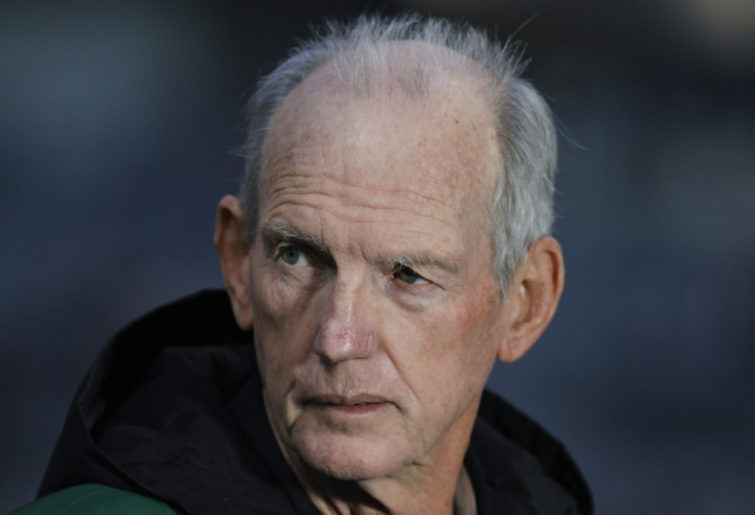

I asked Roy Masters what he thought was the earliest version of this in the NRL and he cited Wayne Bennett’s comments made ahead of the 2012 Indigenous All Stars match, which were widely publicised at the time, with many suggesting that they would be adopted in the not-too-distant future.

(Photo by Mark Evans/Getty Images)

That turned out to be almost a decade, but in this time TRL adopted the rule and kept it alive.

I emailed Tom Longworth, the Managing Director of TRL and the person who wrote the rule in that code, and he replied, “we brought it in at the same time/year as the NRL.”

Unfortunately, records of the rule book are no longer available from that era but the answer is conclusive that it was not TRL that invented the six-again concept, but it was TRL who embraced and maintained it in the eight years where the NRL let it lie dormant.

In my research for the Tom Brock Bequest into the Americanisation of sport in Australia, I was reminded that one code keeping alive an idea from another is not that unusual.

An 1800s version of the play-the-ball was part of pre-split rugby but was abandoned in 1878 until reintroduced in 1906 by the Northern Union (rugby league), yet it was still used in the way Canada played rugby.

To clarify, Canada continued to call its competition ‘rugby’ long after it had not only maintained the play-the-ball, but innovated the flat-line scrummage, aka ‘scrimmage’.

Moreover, this is led to the US and Canadian gridiron developing the snap, which was a play-the-ball with the foot before it became via the hand, much like we see in today’s Super League, where players roll the ball without an attempt to heel it back.

Eventually, this did go through one more change in the North American gridiron games and has remained relatively consistent as the snap we know today.

Now, with respect to the latest NRL tweak to the rules, the question is whether blowing a penalty can succeed as a compromise in ‘speeding up the game’ while ensuring that teams do not game the system by accepting the six again while the team with the ball is back up against their tryline early in the count.

Without knowing, it seems that deciding on the 40m line as the cut-off is consistent with other NRL rules – the 40-20 for example – in that this part of the field is still seen as a no-man’s land where the ball-handling side does not have a meaningful advantage.

It also coincides with being outside of the part of the field known as yardage, an area where the ball-handling side is conservative in running more hit-ups with less passing out wide while the opposition is especially aggressive attacking for the ball.

Factoring in the average metres per carry over a set of six, one can argue that a penalty is in alignment with the aforementioned position/possession values described above and why awarding the penalty is specifically from the yardage area of the field.

Unavoidably, the penalty within 40m will impact other areas of the game. The 20-40 rule has already been largely ineffective largely due to it, at best, offering the same reward as a 40-20 but with notably greater risk due to a more precarious field position.

This is not just due to the additional 20m deeper from which one must kick but also the greater likeliness of being earlier in the tackle count. Why would anybody attempt such a kick when the risk is greater than a 40-20 but the reward the same?

Now that a more valuable penalty will be called within 40m, does the 20-40 have a future in the game at all? Not unless an even greater incentive and/or risk mitigation to do so is provided; this would have to outweigh both the value of a 40-20 and penalty.

TRL’s solution has been solved differently. As less time is available to retreat from the proverbial ruck in this faster-paced game, if the player who has made the touch (or the would-be tackler leaving the ruck to get back) maintains their line of retreat and/or stays out of play, there is no issue because the ball-handling side has been given clear notice.

If the defender changes the line of retreat, which ‘shadows’ the ball carrier, there will be a zero tackle (as their six again is called) and play will continue. However, should the ball-handling side attempt to milk a penalty by running into said defender, the ball will be turned over to the opposition.

There is no correct answer in solving the gamesmanship employed by coaches and players.

One thing we always need to evaluate, however, is time. Waiting and watching is crucial and cannot be replaced by rushed decisions since there will never be enough play-the-balls and data to analyse, should we simply decide that a quick result that we believe to be correct should supersede any good data-driven research.

For now, the blunt machete cutting down the 40m line seems to be doing the job but there may come a day when the NRL will need to look for a surgeon’s scalpel to make the right incision to the game.

I do see an opportunity where the interpretation from TRL can be successfully implemented into the NRL, as it also achieves the goal of ‘speeding up the game’. But, to end on a question, will we ever be at a place where the game is fast enough?