It’s a mystery the Australian team wasn’t arrested by Indian authorities. They didn’t even try to hide their actions.

In full public view, again and again, the Aussies committed larceny in a foreign country. It started small, as it so often does with criminal action. Then, with each successful theft, their confidence grew and they became more and more brazen. The time for petty crime was over. So the Australians set about planning the greatest robbery in the history of ODI cricket.

One run. Three runs. Seven runs. Seventeen runs. Eighteen runs. Those were the narrow margins of five victories that helped a motley Australian team steal the 1987 World Cup. The side won two other matches and they were the only victories which were mildly convincing. Both came against minnows Zimbabwe.

Unproven. Inexperienced. Bereft of form and momentum. Australia had nothing going for them.

There were only eight teams involved and Australia, in the years leading into the tournament, had been comfortably worse than four of them. They had no right to make the final, let alone win it.

In the three years prior to the 1987 World Cup, Australia ranked just fifth for ODI win-loss records, and wern’t anywhere near fourth. Against those four better-performed teams – West Indies, Pakistan, England and India – they had a pitiful win-loss record of 17-28.

Allan Border’s men entered the World Cup on a run of five consecutive losses. They had also won just five of their previous 20 ODIs in Asia before heading to India and Pakistan for cricket’s showpiece event.

They had neither good long-term form, nor reasonable recent results. They were devoid of both an experienced line-up and a team studded with exciting young stars.

Captain Border aside, the remainder of the squad entered the tournament having played, on average, only 22 ODIs each. Incredibly, three Australians made their ODI debuts on the way to the finals.

Unproven. Inexperienced. Bereft of form and momentum. They had nothing going for them.

Have a look at the pre-World Cup ODI records of each of the 14 players Australia used in the tournament, starting with the XI that won the final:

David Boon

26 years old: 1280 runs at 33

Boon had made a reasonable start to his one-day career but had yet to produce a breakthrough performance against one of the powerhouse ODI teams.

Geoff Marsh

28 years old: 1179 runs at 32

Marsh, too, had been reasonable but had struggled against the pace-heavy attacks of the West Indies, Pakistan, England and New Zealand, averaging just 26 versus those teams from 24 matches.

Dean Jones in action with the bat. (Chris Cole/Allsport)

Dean Jones

26 years old: 1424 runs at 41

Jones was a rising star with huge promise. But even he had question marks over his ODI game, having averaged just 26 in his 12 matches away from home.

Allan Border (c)

32 years old: 3969 runs at 32

Comfortably Australia’s most accomplished ODI cricketer yet, with an average of 32, Border still didn’t rank among the truly elite ODI batsmen of this era.

Mike Veletta

23 years old: 5 runs at 2.5

A speculative pick, greenhorn Veletta had played only two ODIs prior to the World Cup.

Steve Waugh

22 years old: 928 runs at 34, 41 wickets at 30.

At just 22 years old, Waugh was already arguably Australia’s best ODI cricketer thanks to his tremendous all-round value.

Simon O’Donnell

24 years old: 552 runs at 24, 43 wickets at 33.

Hard-hitting all-rounder O’Donnell had been solid at home but had laboured badly in eight matches overseas, averaging 16 with the bat and 42 with the ball.

Greg Dyer

28 years old: 51 runs at 51

A very recent addition to the ODI team, Dyer was a decent gloveman but a limited batsman who would go onto finish his 23-match ODI career averaging just 15 with the blade, often hidden away down the order at eight.

Craig McDermott

22 years old: 43 wickets at 37

He might have been fast, aggressive and talented, but McDermott appeared too raw for international cricket at this stage. He had floundered in his six matches in Asia, averaging 65 with the ball.

Tim May

25 years old: debutant

May made his ODI debut at the World Cup and would go on to average a lofty 45 with the ball across his 47-match career.

Bruce Reid was Australia’s top bowler before the ’87 World Cup. (Adrian Murrell/Allsport)

Bruce Reid

24 years old: 40 wickets at 30

With 33 caps to his name at this stage, Reid was Australia’s most accomplished one-day bowler. Yet he still had fewer wickets in the format than Nathan Coulter-Nile currently does.

Then there was the leftover trio who, while not picked for the final, played in earlier stages of the tournament.

Tom Moody

22 years old: debutant

Another speculative pick who made his debut over in India, Moody had only eight List A matches to his name when he was named to the squad.

Peter Taylor

31 years old: 13 wickets at 31

New to international cricket despite his age, Taylor had been a shock selection to make his debut for Australia nine months earlier.

Andrew Zesers

20 years old: debutant

The Australian selectors really were just taking long shots in this tournament. Zesers had played only seven List A matches and was barely out of his teens.

How? That surely is the key word bouncing around your head after scanning that squad. How is it possible for an out-of-form team brimming with rookies and strugglers to win a World Cup? Away from home, no less.

Australia began their 1987 World Cup with the greatest of escapes. Their first match was in Chennai against India, who were the defending World Cup champions, having upset the mighty West Indies in the 1983 final.

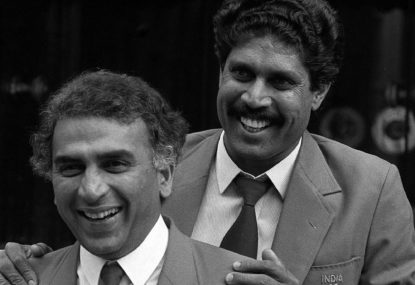

The hosts boasted a strong batting line-up built around two of the greatest cricketers in Indian history, champion all-rounder Kapil Dev and legendary opener Sunil Gavaskar.

Complementing them in the top seven were a host of other players who would end up having fine ODI careers. Among them were elegant strokemaker Mohammad Azharuddin, aggressive all-rounder Ravi Shastri, powerful hitter Navjot Sidhu, and reliable middle order accumulator Dilip Vengsarkar.

Against this long and talented batting line-up, Australia needed to post a good total after being asked to bat first. They were handed a terrific platform by Boon (49) and Marsh (110), who put on an opening stand of 110. Then Jones came to the crease and batted with characteristic verve, motoring to 39 from 35 balls. With Marsh batting almost all the way through the innings, Australia got a final push from Waugh (19* from 17 balls) as they finished with 6-270.

That was a massive score in the era, equivalent to 350-plus in modern times. India didn’t care. They cantered towards the target on the back of swift scoring by Sidhu (73 from 79 balls), Kris Srikkanth (70 from 83 balls) and Gavaskar (37 from 32). At 2-207, just 64 runs were needed at well below five runs an over. Australia looked gone.

Sunil Gavaskar and Kapil Dev were cornerstones of the Indian team of the ’80s. (Photo by PA Images via Getty Images)

Then along came McDermott. The young paceman snared four wickets in quick time and suddenly India were 6-246 with Dev their only remaining recognised batsman. The Indian superstar guided them to within 15 runs of victory, with four wickets still in hand, before the hosts imploded.

Dev was the first to go, then India gifted Australia two wickets via run outs. It all came down to the final over. Two off two was the equation when Waugh ran into bowl at number 11 Maninder Singh. The delivery rattled the stumps, deflated a nation and handed Australia an unlikely win.

Australia got some respite in their next match against the minnows of Zimbabwe. Border (67), Marsh (62) and Waugh (45*) made runs, O’Donnell (4-39) and May (2-39) took wickets and Australia won by 96 runs.

Then came a battle against New Zealand and another thrilling finish. Inclement weather saw this match reduced to 30 overs a side after first being pushed into a reserve day. Border’s side adapted extremely well to these unique circumstances, batting first and sprinting to 4-199 at a run rate of 6.63, which was scorching back in the 1980s. Boon (87 from 96 balls), Jones (52 from 48) and the skipper himself (34 from 28) were all impressive.

The Kiwis faced a stiff task. Yet this challenge looked far less intimidating after they had bolted to 0-83 in the 12th over. When that opening stand was broken, Kiwi maestro Martin Crowe tore into the bowlers, hammering 58 from 48 balls.

Once more the match hung on the final over. Once more Australia were the underdogs. Once more Waugh came to the fore. The young Aussie all-rounder had to defend seven off the last over, with Crowe at the crease.

He might have retired from cricket as a top-order batsman, but Steve Waugh was a clutch bowler in the earlier days of his career. (Mandatory Credit: Mike Hewitt/Allsport)

Crowe gave himself room, looked to loft over cover but was dismissed by a great running catch by Marsh in the outfield. The very next ball, a yorker castled Kiwi keeper Ian Smith. Waugh finished the job by collecting the ball in his follow-through to run out Martin Snedden at the non-striker’s end and then conceding just two runs off the final three deliveries. Australia again had got out of jail.

Next up was a rematch against India, who this time comfortably won by 56 runs. Australia now needed to win their next two matches to be assured of making the semi-finals. The first of those fixtures was yet another heart-stopper against the Kiwis.

Australia batted first and made a good score of 8-251 on the back of 126* from Marsh, who was having a phenomenal tournament. In response, New Zealand were doing it easy at 3-173, needing just 79 runs to win.

This time, it was the golden arm of Border which intervened. The Australian skipper had barely bowled all tournament but took the ball himself and grabbed two quick wickets to spark a Kiwi collapse of 7-61.

With that close win and a far more comfortable victory over Zimbabwe a few days later, Australia were in the semi-finals. It seemed, though, after qualifying for the knockout stages via three very narrow wins, that their well of fortune was due to run dry.

Australia were faced with tackling a gifted and in-form Pakistan team on their home turf in Lahore. The second-best team in the world after the West Indies, they had cruised into the semis with five consecutive wins followed by a close loss against the Caribbean kings, who had a disappointing tournament, crashing out before the semi-finals with just three wins to their name.

Pakistan had two of the world’s best ODI batsmen in Javed Miandad and Saleem Malik, one of the greatest all-rounders in history in Imran Khan, and two born wicket-takers in Wasim Akram and leg-spinner Abdul Qadir. They were a truly formidable unit.

Australia batted first and once again their top order of Boon (65), Marsh (31) and Jones (38) did a good job, steering them to 2-155. Then Veletta played one of two crucial knocks in the knockout stages. To that stage of his ODI career, he had just 48 runs at an average of 12. Against Pakistan he doubled that total in one innings, clipping 48 from 50 balls to help his side post a daunting total of 8-267.

In response, Pakistan got off to a horrendous start, slipping to 3-38, only for Miandad (70) and Khan (58) to drag Pakistan back into the match with a 112-run stand after Australia had one foot in the final.

At 6-212, the hosts needed 56 to win from 37 balls. Miandad remained, and with him Pakistan’s hopes. Or at least they did until McDermott once more swung a match with a decisive spell. After Reid had removed Miandad, he took three wickets inside two overs, including the final dismissal as Pakistan fell 19 runs shy of victory.

Australia, quite extraordinarily, were in the final. It had taken four anxiety-inducing wins to get there.

In front of a mammoth crowd at Kolkata’s colossal Eden Gardens, England were the last opponents remaining, riding high after beating the Windies twice in the group stage.

Border won the toss and decided to bat first, following the formula that had got him and his to the final. Once more Australia’s top order delivered, guiding them into a solid position at 2-151.

It had been slow going, however, for Boon (75 from 125 balls), Marsh (24 from 49) and Jones (33 from 57). Aware the innings needed some impetus, Border sent out McDermott at the fall of the second wicket as a pinch hitter. The bowler duly whacked 14 from eight balls before Border, Veletta and Waugh combined to wallop a further 81 from 66.

Veletta had produced a stunning knock of 45* from just 31 deliveries, an innings of extraordinary pace in that era. Australia had stunned England by adding 65 from the final six overs, a late push which hauled themselves to a good total of 5-253.

Gatting followed through with the reverse sweep, got himself into a tangle and coughed up a catch to Greg Dyer, and with it, the World Cup.

Solid as the target that been set was, England had this tricky chase well under control at 2-135 with Bill Athey (58) and skipper Mike Gatting (41) bolted to the crease. Then came one of the most infamous brain fades in cricketing history.

Opposed to the modest part-time finger spin of his opposite number, Border, Gatting decided to try a reverse sweep. Had he left the ball go it would have been a rank leg-side wide. Instead, he followed through with this audacious stroke, got himself into a tangle and coughed up a catch to Greg Dyer, and with it, the World Cup.

England did not concede. A sprightly innings from Allan Lamb (45 from 55 balls) kept them firmly in the contest. Then a cluster of boundaries from Phil Defreitas (17 from ten balls) brought the Old Enemy to within striking distance of a famous win. When he launched McDermott for a towering six over long on, followed by a chipped boundary over midwicket, just 20 more were needed with a ball and two overs left.

But the wicket of Defreitas by Waugh was too much for England to handle. They lost by eight runs.

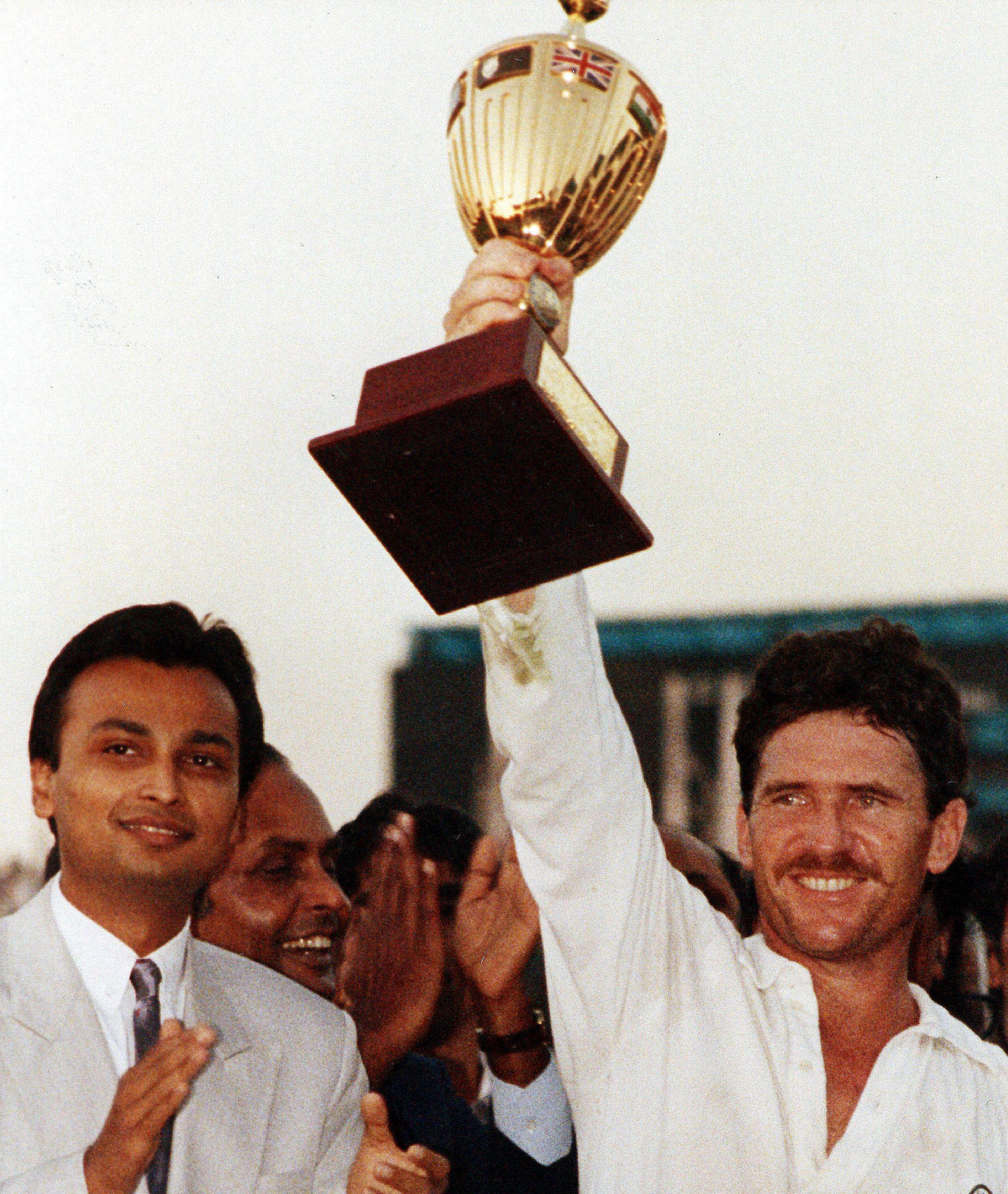

You would imagine the Australians, having engineered a shock World Cup win, the country’s first, would have erupted into rapturous celebrations. Instead, their on-field reaction was muted. More than anything, the Aussies looked exhausted, having scratched and scraped and scrounged for yet another victory. It seemed the collective impact of five nerve-racking wins had finally caught up with them.

Even more than you might imagine, this win was of enormous significance. Australian cricket had just gone through one of the darkest periods in its history during the early-to-mid 1980s. Not only had the ODI team been a shambles for years, but so had the Test lineup.

In the five years prior to the World Cup win, the Test side had won just nine out of 45 matches. Suddenly, with this unexpected Cup triumph, a blinding light was illuminating the end of a long, dark tunnel.

Immediately Australia’s fortunes turned around in both formats. They became a commanding ODI side, with a 35-14 win-loss record across the three years which followed. In that same period they also improved hugely as a Test outfit, winning nine of their following 14 five-day matches and shocking England once again, this time by thumping them 4-0 in their own backyard in the 1989 Ashes.

The 1995 Test win over the West Indies in the Caribbean is widely considered to mark the start of Australia’s famous golden era, during which they ran roughshod over world cricket for more than a decade. The genesis of this era, however, can be traced back to the 1987 World Cup.

Australia entered that tournament with their reputation in tatters after years of woeful performances in both formats. They emerged from it as a cricketing nation reborn.

Written by Ronan O’Connell

Ronan has been a reporter for 15 years and now travels the world as a photojournalist, contributing words and images to more than 70 magazines and newspapers across the US, Europe, Asia, Middle East, Canada, Australia and New Zealand. He’s on Twitter @ronanoco.

Design and editing by Daniel Jeffrey

Image Credit: All images are Copyright Getty Images unless otherwise stated.

Final image of Allan Border lifting the World Cup is credit: AP Photo/Sondeep Shankar.