At Suncorp Stadium on Friday night (when else would it be) the Panthers, rank outsiders with the bookies and most rugby league viewers, were locked at four-all with their much-fancied opponents, the Broncos.

The young Penrith team, bolstered by the surprise inclusion of star playmaker Jamie Soward on his return from injury, were within striking distance of a much-needed victory away from home.

I’ve officiated in NRL games at that famous Brisbane stadium and it’s not like the old ‘Sandcorp’ days, where the surface deteriorated with every step. Some years ago you could have arranged a game of fairies versus leprechauns and they would have made the surface shift like a dune at Wanda beach.

Not so in season 2015. I ran touchlines there in NRL matches at various times for seven years and the ground underfoot is now what you would expect from a Sunshine State icon. Far be it for me to pretend to be a horticulturalist, but it is now as firm and solid as other grounds I’ve been to north of New South Wales, namely Townsville, Darwin, Cairns and Mackay.

So you’d think someone who has played at the ground more times than I have officiated there would know a kicked ball will hit the deck and fly.

With 17 minutes to play Darius Boyd, also a surprise starter, grubbered a kick in-goal which looked like it was heading towards Caxton Street for a Fourex and a Bundy rum chaser. The ball took a bounce prior to the dead ball line and headed off towards the bar, when Penrith fullback Matt Moylan trotted over the dead ball line a couple of metres, pocketed the ball from the air and headed off towards the 20m line for a seven-tackle set.

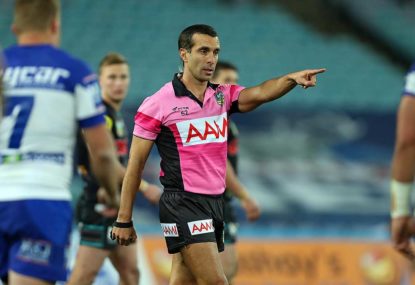

Referee Matt Cecchin is a man for whom I have tremendous respect. We enjoyed a whole finals run together in 2011 that went right through to the grand final. Cecchin halted Moylan mid-stride: no dice, fella, you’ll have to take a drop kick.

The Panthers were bemused, if not a little annoyed at the call. Because everyone could see the ball was out, Moylan was clearly out, so it’s a Penrith ball, right?

Well, no. It wasn’t. Cecchin correctly ruled a goal-line drop out.

In season 2015 unless the ball touches the dead-ball line, touch in-goal-line or beyond, you are going to need to leave it alone until it does so or risk surrendering possession, as the Panthers did on Friday night.

The law for the dead ball line is different to the law that applies to the touchline, just the other side of the corner post. Had Moylan done exactly the same thing with the kick crossing the touchline 10 metres from the tryline it would have been a Penrith scrum feed. As it stands, and has done for several years, the ball is not made dead by the attacking team if a defender plays at the ball before it naturally runs its course.

The reasoning for the application of the law this way is to give the attacking side equal opportunity with the defending side. Think about the Tigers’ try to James Tedesco in Round 8 against the Bulldogs. Kevin Naiqama was in mid-air beyond the dead ball line when he flicked it back to Tedesco to touch down for a four-pointer. More famously, the 2008 Centenary Test saw Greg Inglis dive over the line after a kick and hoist it behind his head for Mark Gasnier to claim a try.

Allowing a defender to snatch the ball in these situations denies a potential try. To give them a seven-tackle set from the restart simply isn’t equitable. The reward is preventing a try, not the double whammy of gaining possession as well.

How did we get to this point where we are seeing a rule for one part of the field (dead ball line/touch in-goal) and another for the other 200 metres of touchline that constitutes the rest of the playing field?

Well once upon a time the law was the same. A rolling ball, on its way out towards any of the lines, being picked up by a player standing outside the field meant his team secured possession. The kicking team made it out, because they were the last to touch it inside the playing field.

However, as happens so often in our great game, coaches exploited the law. Cast your mind back to the early 2000s when Brian Smith (among others) encouraged his fullback to plant one foot on the dead ball line and swipe the ball dead with one hand. A perfectly weighted grubber kick that was to sit up two metres before the dead ball line was rendered a 20m restart by the likes of Brett Hodgson and Ben Hornby. There was no reward for a terrific kick and before long every fullback and winger in the comp was doing it.

The commentators hated. The fans hated it. The referees hated it. In the end the NRL hierarchy hated it too and collectively the game wanted the practise stamped out. Gone. Cast into the Wanda sand dunes and never to be seen again.

The law-makers obliged, and the NRL referees were told to implement a different interpretation of Section 8.2 of the Laws of Rugby League. No longer shall a player reach in-goal to make a ball dead and gain the advantage of the 20m restart. Of course this didn’t extend to the touchlines, because no-one ever did it in that part of the field, so it was left out.

Thus the infamous ‘pane of glass’ was decreed and the match officials instructed to enforce it.

Pane of glass? To understand this you need to imagine a pane of glass extending vertically along the dead ball and touch in-goal-lines. A bit like an ice hockey rink, but only around the in-goal. Now if the ball was grubbered in-goal the fullback was permitted to stand outside the pane of glass and touch the ball to get his 20m optional kick. However, if he reached through the pane of glass to touch the ball he would be denied the 20m and would be forced to the goal-line for a drop out.

Simple? Well, sort of. A lot of questions remained, such as was one foot in and one out permitted as long as the ball crossed the pane of glass? What about shielding the ball and it bounces up to hit the defender? Not to mention the logic of reaching ‘through the glass’. There were a lot of what-ifs and the NRL and its referees have been grappling with this for the past decade.

Now there is no pane of glass and it doesn’t matter whether you’re out or not: if the ball hasn’t bounced its way dead via the attacking team it’s always a goal-line drop out.

Matt Cecchin would have surely preferred to have used his discretion on Friday night and judged that no attacker is anywhere near that ball and the ‘fair’ call would be a Penrith ball. Not so, unfortunately. In these decisions common sense made way for ‘consistency’ a long time ago. There is no discretion available to the officials.

For what it’s worth I suggested to Tony Archer a variation on the pane of glass that I thought the average fan would have a better chance of understanding. I called it the ‘fence line’, hoping the interpretation of the law would be a bit clearer.

Think of the dead ball line being your back fence. You own an apple tree that grows on your side of the fence and the branches of the tree extend in all directions, yielding lovely fruit. Now as I see it if your neighbour has the branches growing over his side of the fence then the fruit is fair game – he is entitled to the apple that hangs over it. Otherwise if he reaches over and takes the apple from a branch over your yard, then he’s stealing it from you.

By this understanding Matt Moylan would have been entitled to take the Broncos’ ‘apple’ on Friday night. Darius Boyd had kicked into the Panthers’ yard. The apple no longer belongs to Darius – Matt is entitled to snatch it and head out to the 20m line savouring the sweet, juicy flavour of a seven-tackle set.

However, that’s not how it is applied and the fans will have to deal with it. The game is demanding a black and white interpretation in all areas of the game and common sense, or the referee’s judgment, has been sidelined.

If you have any better ideas put them in the comments and we can discuss a solution.