The many coloured inks of the 18 signatures on the Australian ‘team sheet’ have long dried. The signatories have all passed on but for the youngest member of the side.

But the stories around those 56 days on the voyage and the 112 days of brilliant cricket (of the 144 days spent on tour in Great Britain), have become the stuff of lore, taking on a life of their own in the telling and re-telling over the past 69 years.

It has often been asked, was the 1948 Australian side the best Test team of all time?

Were they better than Clive Llyod’s West Indies of the 1980s which boasted the jaw-dropping exploits of Vivian Richards, that were all but overshadowed by the most fearsome battery of fast bowlers cricket has ever known?

Were they better than Steve Waugh and Ricky Ponting’s Australia of the Nineties and Noughties, who beat all comers?

Were they better than Warwick Armstrong’s 1921 side which hammered the English on that tour when nothing that the home team did could stop the juggernaut?

Those are debates that will go on forever, and there will never be a clear answer, and indeed there should not. For greatness does not need to be counted in the singular.

What is not open to debate is that on the 1948 tour of Great Britain, the Australians under Donald Bradman played 31 first-class fixtures and three other games across the length and breadth of England and Scotland, and did not lose a single match. They thus became the first Test team to tour Britain and not lose a match, earning themselves the sobriquet of ‘The Invincibles’.

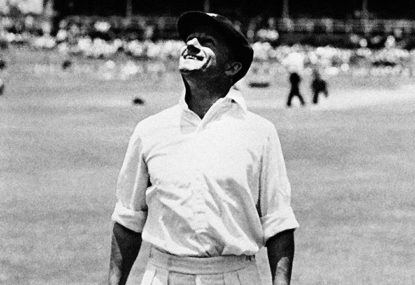

In the Summer of ’48, Don Bradman, at the age of 40, led a team of players across the oceans with intent, with resolve, with enormous talent in their ranks, and with the dogged will to win all that they could.

They showed the world that, at least for that wonderful post-war summer, they were truly Invincible.

[latest_videos_strip category=”cricket” name=”Cricket”]

After years of destruction and loss of human life, and in a Britain where the populace continued to face rationing, this Australian team brought back the joy of cricket at its very best. Bradman had announced before the tour that it was going to be his last and, combined with the Australians’ swashbuckling style on the field and the swagger on and off it, this was a breath of fresh air to the thousands clamouring to get into the grounds to witness history being made.

While the result of the tour was not uniformly pleasing to the peoples of the two nations, the quality of the cricket was of the highest order.

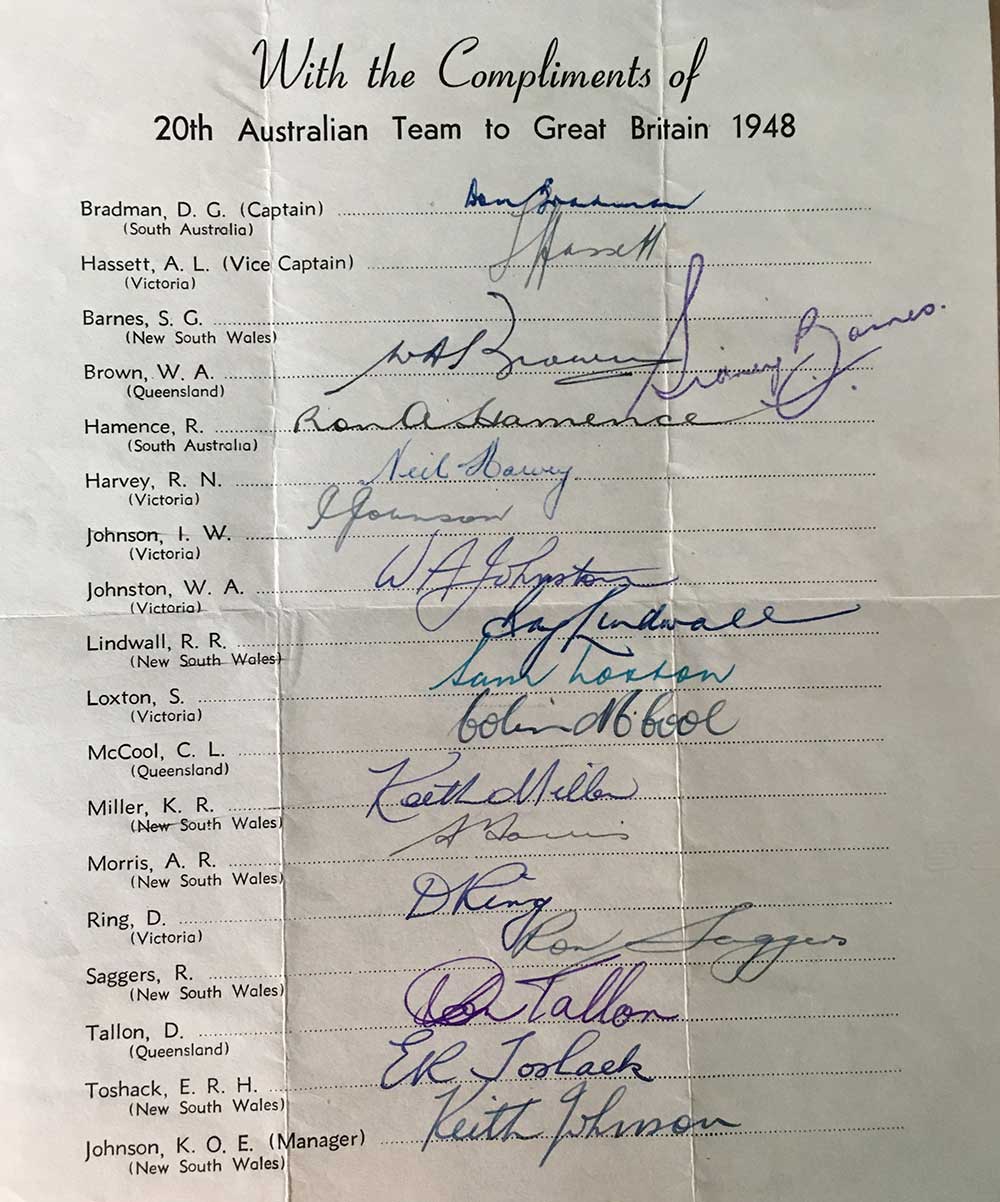

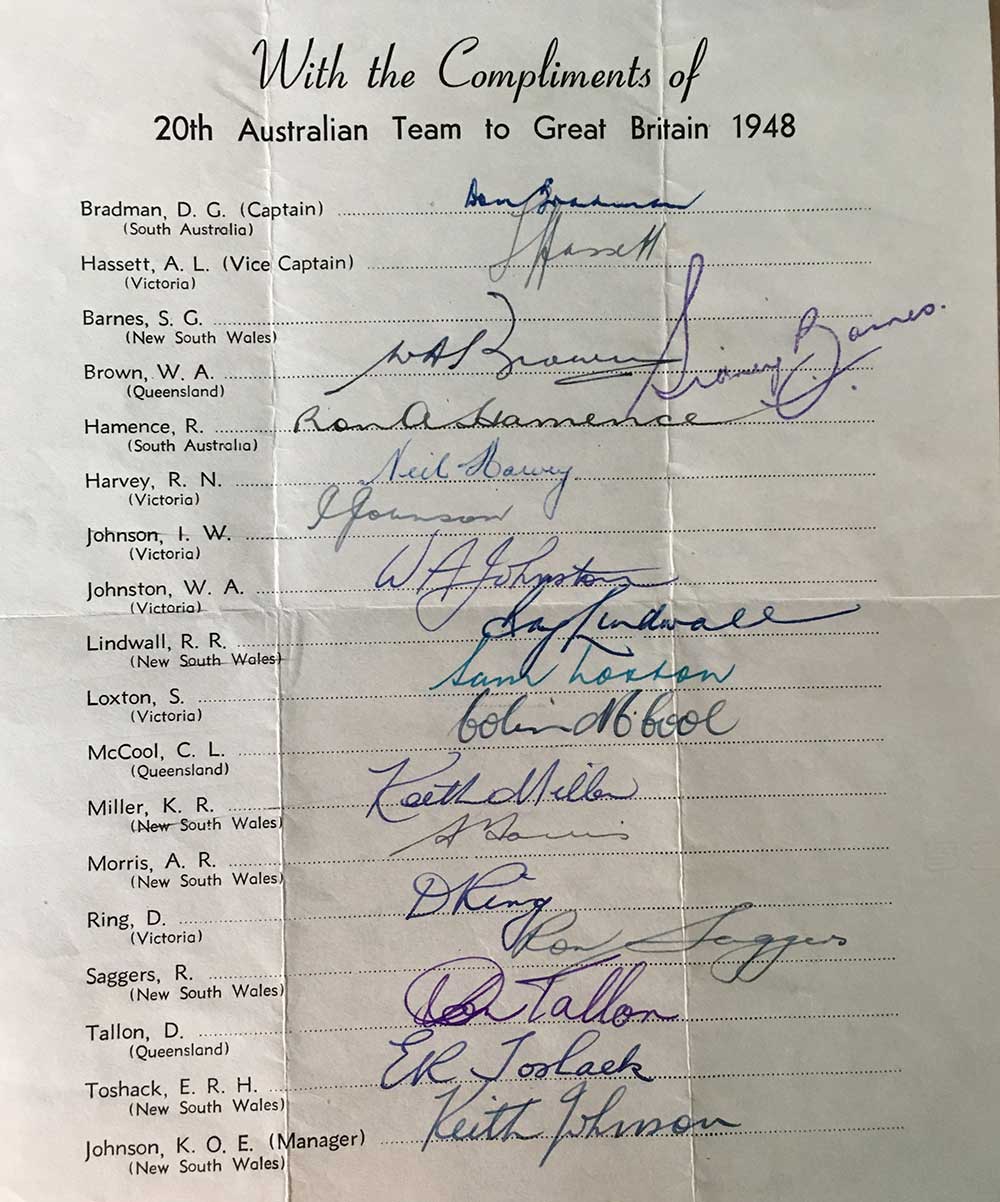

The 1948 Australian team, besides Bradman, comprised Lindsay Hassett (vice-captain), Arthur Morris (co-opted selector), Sid Barnes, Bill Brown, Ron Hamence, Neil Harvey, Ian Johnson, Bill Johnston, Ray Lindwall, Sam Loxton, Colin McCool, Keith Miller, Doug Ring, Ron Saggers, Don Tallon, and Ernie Toshack.

Other than the 26 of the 31 first-class matches, they won four of the five Tests (drawing the third at Manchester thanks to rain) by, successively, eight wickets, 409 runs, seven wickets, and an innings and 149 runs. Bradman and his batsmen failed to make 200 only twice on the entire tour, while his bowlers dismissed the opposition for less than 200 an astonishing 37 times, and seven times for under 100. They scored more than 350 twenty-four times, while the highest score against them outside the Tests was 299 by Nottinghamshire.

Bradman’s men won half their 34 matches by an innings. The team’s 50 centuries were shared by 11 players, seven of whom passed 1000 runs.

Those are staggering numbers, for any team, under any circumstances. When it is achieved on a single tour over a three month period, it is truly astounding. It is little surprise the team earned the Invincibles tag.

It is also no surprise therefore that something like the side’s official team sheet, which is a single sheet of paper autographed by this incredible team, should be a treasured item.

Frank Keating, writing in Cricinfo almost 20 years ago, described how as a ten-year-old in 1948, he sent off his autograph book to Don Bradman with a request to sign and mail it back to him:

“I posted my autograph book off to Worcester, with an SAE for safe return. It contained a few Gloucestershire heroes from the summer before, and I addressed it to Mr Donald Bradman himself. By return came a single sheet. The whole touring party had signed. What awestruck privileged joy.”

I can fully appreciate how he felt, for I felt that joy and thrill in no small measure when I received my own copy a few weeks ago in the post, even if mine was not despatched to me by The Don himself.

Keating wrote:

Half-a-century on, I see them still, headed by the captain’s neatly rhythmic joined-together writing: ‘D. G. Bradman’- both full-stops meticulously in place. I drooled over the neat upright ‘W. A. Brown’ and the cack-handed, more squiggly ‘A. R. Morris’ and his fellow leftie apprentice, schoolboyish ‘Neil Harvey’.

School-masterly and precisely formed was ‘R. A. Hamence’, but ‘Colin McCool’ and ‘D Ring’ were almost illegible hieroglyphics, as you might expect from leg-spin tweakers.

And the mesmerising all-rounder hero stood out, of course, seeming to sign ‘eith iller’ in a readable sub-copperplate, and then adding the capitals K and M in a couple of gorgeously bold and flowery flourishes.

The two wicket-keepers’ hands were both trim, straight-forward and standing up: ‘Don Tallon’ and ‘R. A. Saggers’.

All is not as it seems however, as far as this particular set of autograph sheets is concerned.

If one looks a bit closer, the mercurial Sidney Barnes’ signature does not quite appear next to his name, nor exactly on the ruled line it is supposed to be confined to, and seems almost printed on the paper.

And, as always with Barnes, there is a story behind it.

As Keating explained, and contemporary accounts testify, “on the liner Strathaird coming over, captain Bradman and manager Keith Johnson, both hot on PR, had given each player a huge sheaf of these blank sheets headed by the Australian crest and told them to sign each one and then pass them on. In all, 5000 were filled.

“It was a fearful chore, and only the ferret-sharp Barnes had been ready for it. Before embarking he had made a rubber stamp bearing his signature, and when his turn came, he apparently paid a pocket-money pittance to a youthful shipmate to stamp his 5000.”

What is delightful about this little shenanigan, is that, while none of the 5000 ‘team sheets’, including the ones owned by Frank Keating and myself, have Barnes’ actual signature, its mere absence and substitution by a rubber stamp, cleverly inserted, in some strange way, makes these sheets even more unique.

Poetic as Keating’s eloquence is however, what I see on that parchment is a bit different from what he observed.

Where he saw Bradman’s “neatly rhythmic joined-together writing”, I see the bold stroke of the pen that is still solidly imprinted on the page, put there by that same supremely firm right hand which guided the bottom of the bat as the ball sped to all parts of the ground while The Don accumulated his 50,371 runs.

On that last tour, Bradman scored 2428 runs in the 23 first-class matches that he played, at an average just below 90, with 11 centuries, leaving plenty of memories for his fans to cherish.

Where he saw the great Keith Miller, “adding the capitals K and M in a couple of gorgeously bold and flowery flourishes”, I see the image of my favourite dashing war hero running in, gripping the red cherry firmly in his right hand as he prepares to hand out some ‘chin music’ to the next, hapless batsman.

Miller, with his barrage of short-pitched bowling, helped subdue Len Hutton and Dennis Compton, England’s best batsmen, and took the wind out of the English sails. He made life so difficult for Hutton, that England dropped him for the third Test. In all first-class matches on the tour, Miller took 56 wickets at 17.58 and scored 1088 runs at an average of 47.30.

After Bradman, the firmest hand on that page is of the man who opened the bowling with Miller, a bowler I would have given anything to be able to see perform at his peak. His Ashes opponent, John Warr, held that “if one were granted one last wish in cricket, it would be the sight of Ray Lindwall opening the bowling in a Test match”.

In that 1948 series, Lindwall took 27 wickets in Tests, 86 on the tour. Jack Robertson, a Middlesex opener good enough to play for England, ended in hospital with a broken jaw. Compton was carried off, in the middle of a courageous 145 at Old Trafford, after trying to hook a no ball.

A cricket writer in England said of Lindwall, “Most of his cricket was played at the highest level, on the best wickets and against strong opposition. His skill, unaccompanied by histrionics, was something for the connoisseur to savour.”

And then there is Keating’s “schoolboyish” signatory, Neil Harvey. At 19 years of age, Harvey was the youngest member of the touring party, and at the time, the youngest Australian to have scored a Test century, when he made 153 against India during the previous Australian summer.

Speaking about Harvey’s selection, Bradman had uttered these prophetic words, “He has the brilliance and daring of youth, and the likelihood of rapid improvement.”

I wonder, as the youngest member of the squad, and his junior by some 13 years, was Harvey the “youthful shipmate” that Keating refers to, who was made to apply the “Sidney Barnes” rubber stamp 5000 times during that 28-day voyage? If that was indeed the case, it is a bizarre twist in the tale.

Harvey had to wait until the fourth of the five-Test series before he could get into the Test XI, and making place for him was an injured Barnes!

Harvey scored 112 in a first innings counter-attack to keep Australia in contention after they had suffered a top-order collapse. Harvey then hit the winning boundary in the second innings, as Australia took the match with a Test world record successful run-chase of 3-404.

He retained his place for the fifth Test, ending the series with 133 runs at a batting average of 66.50.

The members of that 1948 team, but for Neil Harvey, have all passed on, as sadly has the brilliant Frank Keating. The tales of The Invincible tour will, however, continue to be told long after the current keepers of the few surviving team sheets, including myself, are gone.

And coming generations of cricket fans will continue to react with awe at the achievements of that group of brilliant cricketers who brought back the simple joy of enjoying cricket to a world torn apart by war.

In the meantime, for the coming decades, my personal piece of Invincibles history will adorn my study wall, telling me stories of that magnificent summer of 1948.