The 12th edition of the British and Irish Lions touring New Zealand in 2017 has most of the elements of an almost mission impossible attached.

In the 38 Tests played between the two sides since 1904, New Zealand have won 29, the Lions have won six, and there have been three draws. New Zealand has scored 634 points to the Lions’ 345. Of the 11 editions in the series, New Zealand has won ten and the Lions one.

That outlier triumph was in 1971. One of the great rugby teams in the history of the game, the 1971 Lions were stacked with once in a lifetime players like Willie John McBride, Gareth Edwards, Barry John, Mike Gibson, Gerald Davies, and JPR Williams. The team’s coach was Carwyn James, the finest coach of the amateur era, with Danie Craven and Fred Allen.

Against relatively mediocre Test sides, which included seven new All Blacks and the retired Brian Lochore called up to Test duties on a day’s notice, this great Lions team won a tight series two Tests to one.

To find out why touring New Zealand in the quest to win rugby Tests is such a challenging expedition, even for the cream of British and Irish rugby talent, we need to go back to the first Test in the series, New Zealand versus Great Britain, played at Athletic Park in Wellington on 13 August, 1904.

The rush up to Athletic Park

Like pilgrims to a sacred site, thousands of people – mainly men – travelled great distances by train and boat to be at Wellington’s Athletic Park for the first ever Test played in New Zealand on August 13, 1904, between the national team, in its black uniform, and the Great Britain team, playing in a jersey of red and blue stripes.

There was a national realisation, an almost instinctive understanding from every level of society, that this match was an historic occasion. And so, in weather that was appropriately and unseasonably golden, the bleak field carved from hills that rolled down to the coastline of Cook Strait became a cathedral of rugby.

Let’s board the Mararoa with 370 other passengers as she leaves Lyttelton – the port of Christchurch in the South Island, for Wellington – on the Friday night before the Test, to get a sense of the high expectations and anxieties ordinary New Zealanders felt before the coming Test.

The ship is crowded – “overflowing”, according to a press report – but no one is complaining. There is no care for anything but football. The cabins are full, as are the smoking room and salons. The passageways on all the deck levels are packed. As the ship makes it smooth way through unusually tranquil waters between the South and North Islands, the constant thud of the engines lulls passengers into a fitful sleep.

By five o’clock in the morning, a couple of hours out from Wellington harbour, the ship is alive again, as passengers eat a hearty breakfast.

After a gliding run through the bending canyons of hills that surround one of the world’s most beautiful harbours, the ropes are thrown from the wharf. Passengers scramble down the gangways to the shipping office to book a place for their return trip later that day. Others race to the ornate Wellington railway station building nearby to buy a pork pie and a lemonade.

Then, as if “pursued by seven devils”, the mass of passengers make their hectic rush up to Athletic Park.

The Mararoa steamship. (National Library NZ/Flickr)

You-be-damnedness New Zealand men of destiny

The New Zealand team had been in training for a week. According to a press report, many critics wanted the players to come together at the beginning of August to “play a series of practice matches for the purpose of acquiring combination, which it is suggested is their weak point”.

The most brilliant rugby tactician in New Zealand, Jimmy Duncan, the originator of the five-eighth system of back play, was the coach. In an interview given before the Test, Duncan explained why he believed his team would win.

“I have given them my directions. It’s man for man all the time, and I have bet Gallaher a new hat he can’t catch Bush. Bush has never been collared in Australia, but he’ll get it on Saturday. We are going to stick to our own 2-3-2 scrum formation, and I think we can win.”

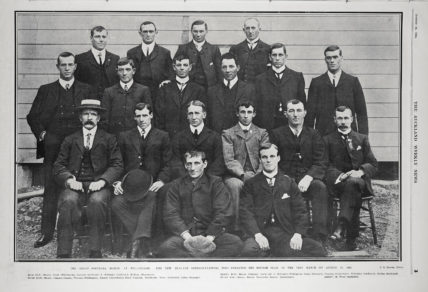

A photograph of the team before the Test shows a confident group of close-cropped, straight-backed men in three-piece suits that seem too small for their swelling chests. They are shaven except for Duncan and manager W. Coffey, who sport fierce moustaches, and hatless except for Duncan (a boater) and a dapper Billy Wallace, who is holding his bowler on his knees.

Dave Gallaher, the hardman wing forward and a Richie McCaw forebear, stares intently into the camera with a hand resting casually in his pocket.

It is a photograph of a group of men who fear no one, and who believe in themselves and their destiny.

The New Zealand rugby union side before their first Test against Great Britain. (Public domain image/Wikimedia Commons)

There is a contrast, even at this early stage in the development of the rugby game, between the cold-eyed scientific approach of the New Zealanders and the British method of public-school enthusiasm and little else (“Play hard, shove hard, ground your man, tackle low, no talking”), which marked the preparation of the locals and visitors.

The British players and administrators regarded the use of a coach, like Duncan, as an unsporting gesture that brought with it the taint of the professional into rugby.

For New Zealanders, right from the beginning of their rugby, coaching by former players skilled in the arts of the game was regarded as a necessary, even essential, part of any team preparation, whether at club or Test level.

It was the obvious way for a team to be prepared, and the bedrock of all the successes New Zealand teams have had for over 100 years. Combinations on the field did not come through serendipity, they had to be worked up before the match so that a rugby side became a rugby team.

And the New Zealand game, unlike the British game, was based on combinations, trying to use all 15 players on the field. A year after their first Test in 1904, the New Zealanders – now dubbed the All Blacks – enthralled crowds and experts through Britain and France with their expansive, ‘all backs’ game.

This inclusive style was grounded in the rugby truth that 15 players with skills and combinations will usually defeat a side playing eight forwards with only shoving skills and seven backs with no muscularity or physicality in their play.

A champion team, the New Zealanders reckoned right from the earliest days of rugby in the country, will always beat a team of champions.

The inclusive style, too, was grounded in the national belief that every person was as good as anyone else in any area of national life. New Zealand rugby teams, from school to Test level, have always included players from every class, ethnic group and walk of life, all playing together as a team.

A champion team, the New Zealanders reckoned right from the earliest days of rugby in the country, will always beat a team of champions.

This inclusive ethic meant national teams were and still are genuinely representative teams, from the first Test side in 1904 with its Maori, native-born and overseas-born (Dave Gallaher) players, to the teams that will play Tests against the 2017 British and Irish Lions.

Maori, for instance, had the vote in 1867, the year after the wars over land and sovereignty, between some of the major tribes and the government authorities, had ended. It is no accident, then, that the captain of the 1904 New Zealand side was a Maori, Billy Stead – a five-eighth regarded still by rugby historians as one of the greatest All Blacks, “a scoring machine, steadiness itself, a good tactical kicker, superb handler and of unruffled temperament”.

And it will be no accident that some of the more dynamic players for the All Blacks in the 2017 series will be second-generation Polynesians, a reflection of the fact that Auckland now is the biggest (in terms of population) Polynesian city in the world.

In 1904, Edith Lyttelton, under the pseudonym of GB Lancaster, wrote a remarkable short story, Hantock’s Dissertation, which reveals perfectly the sensibilities at play in the first Test at Athletic Park. The point of the story was to expose the differences between New Zealand life and life in England at the time, and how these differences were creating different types of people in the two countries:

“‘Why,’ said the Man from England promptly turning in his chair, ‘can’t a colonial say “sir”, or touch his hat, or take his hands out of his pockets when he’s talking to his betters?’

“Hantock replies: ‘Respect is outward acknowledgement of superiority … That’s English, and we have sloughed it pretty completely … Suppose a man can cut out a steer, or wheel a mob with the skills of a general … Your colonial reverences that man, whatever his birth – but that doesn’t make him take off his hat to him … And yet there are some idiots who imagine that a colonial is merely a transplanted Englishman. He isn’t anything like it … a colonial is not a product of civilisation, he is a product of the soil … There you get the keynote, then -in the land. You’ll see the New Zealanders in the rivers. They tear out a way for themselves, slap ahead, and ride down to the sea with a reckless you-be-damnedness that is entirely their own.'”

That quality of you-be-damnedness was at the heart of the New Zealand play against Great Britain in 1904, has been in all the Tests played by the All Blacks since then and, certainly, will be during the Tests against the 2017 Lions.

The ‘Minister for Rugby’ has his say

The image of a river in full torrent, smashing over rocks and slipping over its banks, provides a perfect metaphor for the New Zealand Prime Minister in 1904, Richard John Seddon, known throughout New Zealand as the ‘Minister for Rugby’.

Although born in England, with some years spent working in Melbourne, Seddon identified with and helped to create the raw-boned democracy that emerged in New Zealand in the 1890s and has flourished since. He learnt his politics on the wild West Coast, where he became the MP for Westland in 1890. Three years later he was Prime Minister. He died in office in 1906.

A man of commanding presence – in appearance somewhat like WG Grace, with a swelling belly, a handsome face bearded like a grandee – with an imposing manner and endless energy and curiosity, Seddon set the mould for the populist New Zealand politician type that includes Sir Robert Muldoon, Norman Kirk and, more recently, John Key, another ‘Minister for Rugby’ in the Seddon manner.

Richard John Seddon, New Zealand’s Prime Minister during the first ever Lions tour. (Public domain image/Wikimedia Commons)

Help for rugby by a New Zealand politician was not a new thing in 1904. In 1870, the Prime Minister, Julius Vogel, allowed James Munro and his players from Nelson a free passage on the government steamer Luna to play their historic first rugby match in Wellington against a team of locals.

This concession by Vogel set the standard for New Zealand politics, that rugby and government help for the game was a surefire way of establishing public support.

Seddon knew this, intuitively. He knew, too, that rugby could be the epitome of the inclusive New Zealand ethic he was trying to create with his pioneering social welfare programs, including giving the vote to women in 1893.

The popularity of rugby in New Zealand at the time was such that by identifying his government with its spread and success, he was harnessing goodwill for his reforms. As historian Jock Phillips notes: “Seddon was too crafty a politician not to ride on the coattails of rugby.”

“The colonials may be relied on to show the mettle of our pastures”

On the Thursday before the first Test, Prime Minister Seddon invited the British team to a reception at Bellamy’s, the bar and eating place in the Parliament Buildings, setting a precedent that was followed for visiting international rugby teams throughout the game’s amateur era.

A photographer was present to take pictures of the visitors with the Prime Minister. Seddon’s gravitas in the photographs is deceptive. He had been receiving deputations and was running late. He swept into the reception “with an almighty rush” and surprised a journalist from the local Evening Post by grabbing his hand, shaking it vigorously, and welcoming him to New Zealand.

He also welcomed an artist from the New Zealand Free Lance, a weekly newspaper, “with immense enthusiasm” and asked: “Had a pleasant trip?”

In his speech of welcome, Seddon remarked that the last British team had been captained by a Seddon (enthusiastic cheers). They often had scrums in Parliament, many tries and often a goal (laughter). He would say nothing of offsides, though (cheers).

“A country whose youth takes kindly to rugby produces a finer and better manhood than it would were ping-pong their form of physical effort.”

The New Zealand rugby team, playing without numbers on their jersey, he continued, represented an affirmation of the egalitarian “one-man, one-vote” system (cheers).

This point about the link between democracy, on and off the field, was taken up in a long editorial published on the morning of the Test in the New Zealand Times. The editorial had the banal heading: ‘Today’s Engagement’.

Visitors from England to New Zealand, the editorial noted, “have always been struck by the popularity of rugby in the colony”. Competent judges were gratified to see “the competency” shown by the players. And Maori, like Pakeha, had been enthusiastic about the game: “Such sterling players as Ellison, Wynyard, Gage, Hiroa, Taiaroa, and the Warbucks, for instance, will long be prominent in the history of New Zealand football.”

The colony awaited the result of the “pending engagement” with the eagerness it evidenced during the Boer War: “That this should be so is gratifying. No one will deny the impact the manly pastime has upon its followers in teaching self-control and unselfishness … A country whose youth takes kindly to rugby produces a finer and better manhood than it would were ping-pong their form of physical effort.”

The editorial ended on a chord of emphatic nationalism that would have pleased Seddon: “Young, vigorous and ambitious to win, the colonials may be relied on to show the mettle of our pastures.”

“We were playing for the Championship of the World”

The rush to get to Athletic Park had never been seen before in New Zealand for a rugby match.

The electric trams used to take people to the ground for the first time proved to be “inadequate” to cope with the crowds. Cabs, buses, and express vehicles of every sort were pressed into service. By the time the gates were opened at 11am, the crowd was already several thousand strong, the size of a “very respectable attendance at an ordinary first class match”.

By 1pm, the ground was packed, with about 20,000 people banked in “uncountable confusion on the four sides of the ground”. To put these numbers into a context, the crowd was bigger than that for most rugby internationals played in the United Kingdom.

Moreover, in 1904, only two cities in New Zealand, Auckland and Dunedin, had over 25,000 people living in them. There were probably more people crammed into Athletic Park for the Test than actually lived in Wellington at the time!

A reporter made a judgment that remains true of the ground until it was dismantled about 20 years ago: “As we feared, the Athletic Park, which had never had its capacity tested before, was not large enough.”

This is a judgment, too, that will be made of Eden Park in Auckland, and Westpac Stadium in Wellington, where the Tests in 2017 will be played.

A photograph of the crowd on the hill, taken at 1pm, shows it to be tightly packed on top, along its sides and on its lower levels. Only the middle portion of the bank, which was “actually a steep drop was bare of people, although some braves had dug their heels into the sheer clay face to entrench their position on it”.

Another photograph, taken not long before the Test started, shows an elegant crowd in the grandstand. A Union Jack is hanging in the background. The ladies are arrayed in their best dresses and large hats. The men, including Prime Minister Seddon, James Carroll (a Maori, deputy Prime Minister and Colonial Secretary) and the Governor-General, Lord Plunket, are in suits. The captain of the touring party, David ‘Darkie’ Bedell-Sivright, who was injured, sits in the front row, wearing a top hat.

At 2:45pm, a big black banner with a silver fern leaf was raised beside the entrance gate. Just before 3pm, the New Zealand team, clad in their black uniforms, walked slowly onto the field. Jimmy Duncan, dressed in white, strolled out with them to give his players some final advice.

Then the Great Britain side filed out, to the strains of the song ‘Red, White and Blue’.

The New Zealanders welcomed their opponents with “three, short, snapping cheers”, and the British replied with the “long, drawling cheers that a colonial team never uses”. Then the two teams walked towards the grandstand and cheered the governor.

The New Zealanders won the toss and, showing tactical sense, decided to play with the wind, a light northerly, and with the sun on their backs. As the teams took up their positions, and it became apparent that the British were facing the elements, the knowledgeable crowd broke out into cheers.

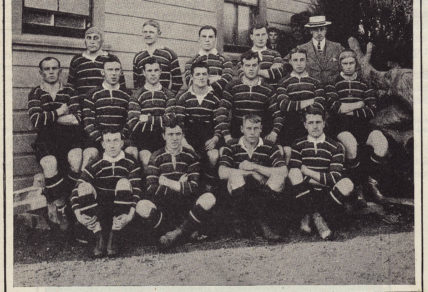

The Great Britain team which toured New Zealand in 1904. (Public domain image/Wikimedia Commons)

A match report indicates that the New Zealanders had trained to use the wind first if they won the toss: “Britain kicked off … Wallace returned with a punt to the NZ side of halfway .. Stead went after the ball and gave it another kick into touch at Britain’s 25 flag … Then came the first run of the NZ backs. Woods and McGregor dashed away, but they were chased straight across the field to the opposite touchline … The NZ rearguard was now bending itself to business … There was premature cheering but because the ball was forward – the try was not a try …

“A scrum was formed and for a breach NZ was given a kick and as Wallace made his preparation his own men spoke anxiously to him, ‘Put it over Billy,’ they said. The crowd was silent but an instant later a disappointed cry was raised as the kick failed. ‘I couldn’t see the posts, I was shaking all over,’ Wallace said after the game.

“Down field the NZ forwards went but a British illegality stopped them, and a second kick in front of the posts was entrusted to Wallace. For the second time he missed an easy chance …

“A fifth chance was missed by Tyler and the crowd was loud with expressions of condemnation, but the crowd changed their murmurings to cheers when a minute later Britain committed another breach and this time Wallace kicked the goal. New Zealand 3 – Britain 0.”

A photograph of this first successful goal by a New Zealand player in a home Test shows the ball soaring high above the crossbar, but just sneaking inside the left-hand post. Wallace is looking anxiously up, as is the holder of the ball (an indication that the wind was quite strong) and several other New Zealanders, one of whom is raising his arm in triumph while one of the props, some metres behind Wallace, is successfully steering the ball through the posts with extravagant body language.

The match report continues:

“What a scene it was. Thousands and thousands of hats and handkerchiefs waving wildly, and twenty-thousand throats hurrahing! That was three minutes before half-time … Britain kicked off from the halfway, and without warning down field dashed Morgan … in the ensuing scramble a free-kick was given to Britain. The angle was difficult, but Harding booted the ball clean through the posts … Britain 3 – New Zealand 3.

“It was only natural that the play should be at time of the deadly kind,” Jimmy Duncan explained after the match.

“It has been a fast spell, and with the exception of two or three flashes, all in favour of New Zealand.”

In their huddle during the halftime break, the New Zealanders decided, like so many All Blacks teams would do in the future, to keep the pressure on in the forwards, to play a tight, swarming, driving game and for the backs to run at their opponents.

As Duncan explained afterwards, “It was only natural that the play should be at time of the deadly kind. You know, we were playing for the championship of the world, and there could no ‘beg pardons’.”

The crowd was not as assured of a successful result as the players. There was, according to one reporter, a “timid” feeling among the spectators, brought on by the fear that the British had held back some of their tricks.

The match report for the second half continues:

“The ball was thrown to the British backs. As it came to Bush he dropped it like a shot on his toe, the next instant it soared past the posts. It was too close to be pleasant … The black backs attacked again, pass after pass, short and sharp, and then McGregor, on the wing got it at last. Six feet from the line he dived over, setting out a scene of excitement rarely seen in Wellington. New Zealand 6 – Britain 3 …

“Morgan took a shot at goal from a penalty, but he missed the kick badly … And when O’Brien missed a high kick, there was nobody to stop Nicholson, who came up fast, from getting the ball. He gave it to Harper, and then sent it to McGregor. The Wellington sprinter finished off a splendid run by scoring near where he had crossed the line before. Again the crowd cheered itself hoarse and waved its handkerchiefs. New Zealand 9 – Britain 3.

“Wallace had another shot at goal unsuccessfully, and the game ended as the ball bounced into touch near the half-way flag. The great crowd rushed the field and cheered.”

Robert ‘Dick’ McGregor, the scorer of both tries for New Zealand, was carried off the field through a crowd that had surged in a triumphant mass across the grass arena.

“Rugby is king in New Zealand”

As the New Zealand team was driven down the hill from Athletic Park back into town, all restraint was thrown aside by the spectators. From streets, cabs and cars, and from house-tops and through open windows, there came a babel of cries: “Good old New Zealand!”

The secretary of the NZRFU later supplied figures showing that the total paid attendance was 21,932. It was estimated that another 5000 lined the hills outside the park. The NZRFU cleared 1760 pounds as its 60 per cent of the gate. A portion of this money was set aside to send a New Zealand team to Britain the next year, thereby helping to meet the 3000 pounds guarantee for that tour.

At the after-match function, Bedell-Sivright told the gathering that a New Zealand team would hold its own against most of the clubs sides, but would struggle to defeat combined sides like Devon.

As it happened, Devon were the first opponents of the 1905 All Blacks. It is hardly any wonder, given Bedell-Sivright’s rather arrogant assessment of the limitations of the New Zealanders, that the 55 – 4 scoreline to the All Blacks was not believed when it was telegraphed through to the Fleet Street newspaper offices in London.

Sir Terence Power McLean, New Zealand’s greatest rugby writer, in one of his last books, The All Blacks, was unequivocal about the importance of the victory at Athletic Park: “It was, without doubt, the most significant result in New Zealand rugby history. The kids from the waybacks had beaten their masters, fairly and squarely.”

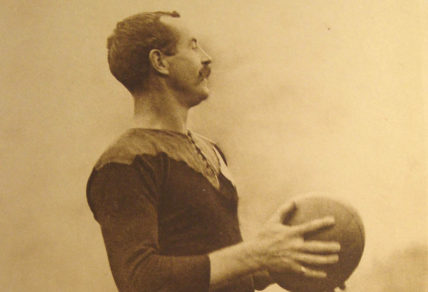

Dave Gallaher, who captained the 1905 All Blacks on their tour of great Britain. (Public domain image/Wikimedia Commons)

The result was celebrated as a victory for the game and the nation. This was the time when the New Zealand passion for rugby and an equally ferocious obsession with winning had its birth.

The passengers on the Mararoa, on their way back to Lyttelton on the Saturday night return voyage, “cheered themselves hoarse” and “shook hands with everyone around them”. Later on, even though they were tired “they wanted little sleep, so they talked football and football and more football, and ultimately found themselves in Lyttelton once once more.”

The weather had been beautiful, the sea smooth, no one was sick and “they had seen the greatest match in the history of New Zealand, and New Zealand had won!”

As the result of the match was telegraphed through to the country’s post offices, there were spontaneous celebrations. “A deafening roar rent the air” at Dunedin when a crowd of 3000 was told the final result. At Timaru, the posting of the result was “the signal for cheers”. Outside the newspaper office at Gisborne, “the Maoris were very excited, and gave a spirited haka.”

The Evening Post, in its reports on the following Monday, was flushed with pride in the victory. It enthused over “the great match” and suggested that “never have the shifting fortunes of the game been followed with so eager a gaze. And never in these parts has a result been so eagerly awaited even in remote hamlets, with such breathless interest.”

In a memorable phrase, the editorial put the first home Test victory by a New Zealand side into its true and last context: “Rugby is king in New Zealand”.

Upane! Upane! Upane! Ka Upane! (Together! Together! Together! All Together!)

In 1904, New Zealand had a population, according to the census, of 888,200 people. About 45,000 of the population was Maori. Prime Minister Seddon told an audience at Lawrence, a small town west of Dunedin, that for the first time since the early 1880s, there were more births in New Zealand, 13,301, than deaths.

The census noted that there had been an upsurge in births in the Maori population. In the years after the end of the New Zealand Wars, between the settler government and a number of the Maori tribes that were determined to retain their land, there had been a decline in the Maori population. Sociologists argued that the task of government in New Zealand was “to smooth the pillow of a dying race”.

The race did not die. It revitalised itself. The Maori birth rate increased.

This had an important consequence for rugby. Maori had an affinity with the game. Rugby’s cleverness, its muscularity and the notion that it was warfare involving cunning tactics on defence and attack on a playing field were all aspects that appealed to Maori.

The Lions will be confronted with the most storied and successful international rugby team in the history of the game.

A sign of this love for the game was evidenced by the fact the first ever major overseas rugby tour was made by a Native side (which included a couple of Paheka) to Australia, Great Britain and New Zealand in 1888-89.

A Maori lawyer and a member of the 1888-89 Native side, Thomas Rangiwahia Ellison, proposed a motion at the NZRFU’s first annual meeting in 1891 that the black jersey with a silver fern leaf be New Zealand’s playing uniform. Ellison captained the first team to play in these colours.

The Maori influence on the All Blacks’ style of play and the impact of gifted Maori players has been a source of great strength and national pride. And it has been an important factor in ensuring that rugby is New Zealand’s national game, and its greatest passion.

Move on now to 2017. The population of New Zealand is, according to the latest census figures, 4,604,871. This population is 74 per cent European. The Maori population has dropped since 1904 in percentage terms to 15 per cent, but is still far and away the largest minority group. However, this percentage drop, which covers a massive increase in real figures, has been compensated by the 7.5 per cent of people with Pacific Islander ethnicity.

Since the 1980s, this Pacific Islander cohort has had a remarkable impact on New Zealand rugby, at every level up to the All Blacks.

The All Blacks that will face the 2017 British and Irish Lions will have a wondrous combination of Maori and Pacific Islander muscularity, size, and passion for the combat aspects of rugby centred (brown power) and the Pakeha qualities of resilience, intensity and the sort of angriness that is summed up in the phrase often used to describe New Zealand forwards: the “cranky South Island farmer” type.

So, as in 1904, the 2017 Lions will be confronted with a whole population that identifies as a rugby nation, the famous ‘stadium of four-and-a-half million people’ concept.

(Photo: AFP)

On the field, the Lions will be confronted with the most storied and successful international rugby team in the history of the game, the All Blacks.

This is a team that has played 552 Tests, won 426, lost 107 and drawn 19 for a winning rate of 77.17 per cent. The team has scored 14,924 points and conceded 7205 for a points differential of plus-7719. Out of the eight Rugby World Cup tournaments, the All Blacks have won three – in 1987, 2011, and 2015.

In the era of the current All Blacks coach, Steve Hansen, the record is even more impressive: a winning ratio of 91 per cent, with 68 Tests played, 62 wom, two drawn, and four lost, with 2356 points scored and 1077 conceded.

In 2016, the All Blacks, after achieving a record 18 successive Test victories, won the prestigious Laureus Award for Sports Team of the Year.

In May, the All Blacks were nominated for the 2017 edition of Spain’s prestigious Princess of Asturias Award for Sport. The team won the award – one of the most eminent distinctions in the Spanish-speaking world – for having become a worldwide icon in rugby, according to the award’s jury.

“The New Zealand team is the most successful team in rugby union history,” the award statement claimed. The All Blacks have shown a commitment to “such noble values as solidarity and sportsmanship.” The team is considered “an example of racial and cultural integration that has contributed to the unity of New Zealanders of different origin, symbolised in the haka, a Maori tribal dance that provides a link to their roots and ancestral heritage.”

Ka mate! Ka mate! (It is death! It is death!)

Ka ora! Ka ora! (It is life! It is life!)

Tenei te tangata puhuruhuru nana nei i tiki mai, i whakawhiti te ra! (Here is the hairy man who caused the sun to shine)

Upane! Upane! Upane! Ka Upane! (Together! Together! Together! All together!)

(AP Photo/Natacha Pisarenko)

Written by Spiro Zavos.

Spiro is a founding writer on The Roar, and long-time editorial writer on the Sydney Morning Herald, where he started a rugby column that ran for nearly 30 years. Spiro has written 12 books: fiction, biography, politics and histories of Australian, New Zealand, British and South African rugby. He is regarded as one of the foremost writers on rugby throughout the world.

Editing by Joe Frost and Daniel Jeffrey

Design by Daniel Jeffrey and James Daly

Lead image a mix of the 1904 team photo (public domain image/Wikimedia Commons) and 2017 British and Irish Lions team photo (supplied to Spiro Zavos by British and Irish Lions)

Photo of Athletic Park is credited to National Library New Zealand/Flickr