It’s that time of year again. Queensland have walked away with yet another State of Origin victory and every man and his dog is laying into New South Wales over various perceptions as to why and how they lost.

While there have been many specific criticisms raised, there was one that seems to raise its head year after year and it’s difficult to ignore. No, it’s not Mitchell Pearce. It’s an issue far broader than one contentious selection. It’s the perceived great cultural divide between the two states.

It’s the difference between the ingrained collective attitude dwelling within the Queensland camp that allows them to overcome adversity year after year and the questionable mental fortitude of a Blues, who appeared unstoppable until it really mattered.

NSW “just don’t get it” and they’ll never succeed until they do. Well, that’s the theory anyway.

The problem is that while this is a simple criticism to put forth, no one can seem to agree what ‘it’ is. Is it desire? Effort? Leadership? Experience? The fabled Queensland Spirit? Does ‘it’ even exist?

In reality, trying to gauge the influence of Queensland’s supposed cultural superiority on Origin and whether or not NSW can emulate or counter it is a far more multifaceted issue than the throwaway line of “not getting it” implies. Where do you even begin?

First things first, culture does not win games. It may come as a shock to some, but players and coaches are what win games and if Queensland didn’t have the players available to remain competitive, any cultural advantage wouldn’t be worth a damn. But we’re talking about two teams that pluck their players and coaches from the same competition in the same country.

Players from both sides come through the same systems together with many playing side-by-side for their respective clubs. There should be a much more even share of series wins then currently stands and for a long time it was decidedly more even. Over the 26 years immediately preceding this Queensland “dynasty” the split was dead even.

Since then, Queensland have had a strangle hold over the series and it can be easy to forget that this current period of Queensland dominance covers essentially a third of Origin’s existence. That’s a sudden and dramatic change in fortunes.

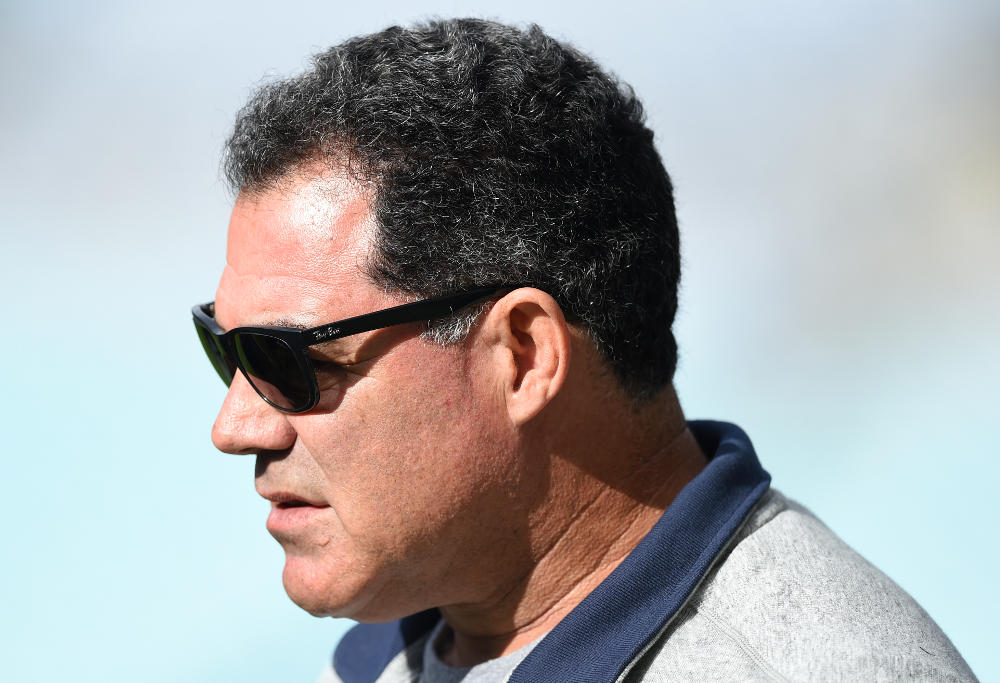

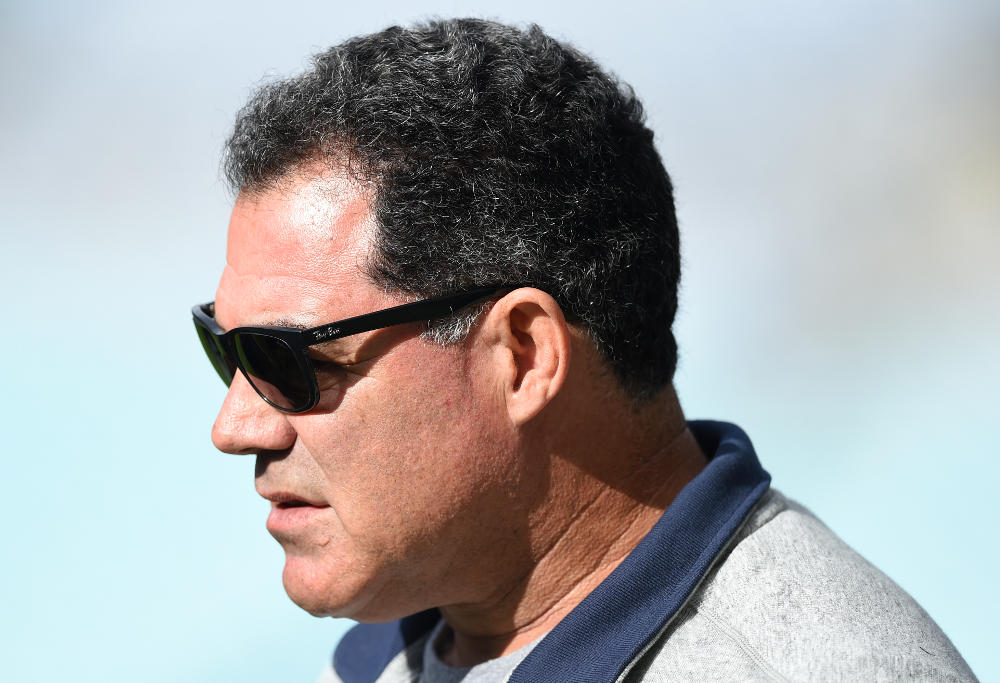

(AAP Image/Darren England)[/caption]

(AAP Image/Darren England)[/caption]

So, what happened? It’s not as if Queensland suddenly stumbled upon a miraculous source of new players while NSW stocks dried up. And history shows that on average the Blues have emerged victorious once every series throughout this dynasty. It stands to reason that if you are capable of winning once every year you should be capable of winning two games and taking out a series more than once over a 12 year period. Right?

It’s here where the “culture” argument begins to gain traction. With all other factors being relatively even, the culture behind the teams seems to be the only real difference between them.

Now, when I talk about culture I’m not referring to some intangible never-say-die spirit that apparently all Maroons naturally possess. I’m talking about how the history of each team has influenced the organisation behind the scenes and the effect that has on on-field results.

Clearly, 2006 was a turning point between the states, but to get a true understanding of their respective cultures we need to go right back to the beginning. Despite how it’s sold, Origin has never been about NSW versus Queensland – the real rivalry has always been between the NSWRL and the QRL and that’s what allows the mate against mate concept to work.

The Maroon players in the inaugural Origin didn’t truly hate the players they were lining up against but they sure hated what those players represented once they pulled those blue jerseys on. The hate, or more accurately the resentment, developed over years of the NSWRL poaching players developed by the QRL with pokie money that the QLR simply couldn’t compete with.

The BRL (the QRL’s premier competition) was constantly treated as an inferior competition despite the players it produced and to this day BRL statistics and results are not included in official player records of the day.

And so, while being derided as a non-event south of the border, the Maroons went into the first State of Origin with no lack of motivation. Finally able to represent their state on an equal playing field the Maroons went on to win a commanding 20-10 victory in a far more brutal and intense match then the Blues were expecting.

Quite simply, the Maroons took the game far more seriously than the Blues did. For the Blues, origin started that night, but for the Maroons, that game was just their first opportunity they’d been given to rise against the perceived self-serving oppression they felt under the shadow of the NSWRL. While Origin essentially started as just another rep game for the Blues, victory for the Maroons was about so much more then a result – it was a declaration of resistance and a restoration of pride for the QRL and by extension the entire state.

This has been the core difference to how the two states viewed the series since its inception. With NSW pride wounded by the northern upstarts they quickly bought into the concept and the all or nothing gladiatorial like contest made winning Origin a matter of state pride in its own right for all involved.

That core difference shaped how both sides have approached origin since then, particularly with their selection policies. NSW used the annual city-country game as a selection trial and this ensured that there was always a focus on having the best players, so the passion and pride players felt for their state was intermingled with a sense of personal achievement.

While Queensland still had access to elite players in key positions, they could not boast the same quality across the board as the Blues and NSW went into most games with the best team on paper – even if those of us hailing from north of the border have never put much stock in the written word.

(AAP Image/Darren England)

This meant that the Maroons were much more reliant on the team’s ability to work as one than individual brilliance. To add to that, Queensland still hated what those Blue jerseys stood for and instilled that hate into new players coming through, further unifying the group against a common enemy.

This focus on standing up to what the Blues represented rather than results themselves led to the Maroons getting a reputation for never giving up, which in turn resulted in some miracle come from behind wins against all odds.

The thing is, for all the motivational surplus which drove Queensland to dominate the first decade of Origin, in the 16 years from 1990 to 2005 Queensland only won four series, though two draws also allowed them to retain the shield. Culture simply does not win games by itself and the Blues may have been late to the party but they soon developed their own successful culture around their own state pride with their own version of the hate.

With the Maroons prized culture matched by the Blues own desire for success, the Blues superior playing roster was starting to pay dividends. While the Maroons remained competitive, the professionalism with which NSW approached Origin ensured that the weight of possession was in their favour.

For Queensland something had to be done and Mal Meninga was brought in to turn things around. As one of the founding Origin players, his first objective was to re-establish the Queensland Spirit.

Now, their culture still lived, the players still bled Maroon, hated the Blues and never gave up, but what had changed over time was how that manifested itself in their approach to Origin. Meninga knew that if Queensland were going to turn the tide back in their favour, the spirit in which they had been playing Origin needed to be present in all facets of their preparation for Origin.

Just like in that first game back in 1980, they had to take Origin more seriously then NSW. Mal had turned the Queensland coaching job into a full-time position.

(AAP Image/Paul Miller)

And so the “Queensland Spirit” became the foundation on which everything else was built upon. Their attitude towards training and their preparation as a whole had to reflect this. The Emerging Origin Camps and pathways set up in previous years to keep Queensland competitive were used to identify the talent and, more importantly, the character of players coming though and their fit into the Maroons systems.

Mal’s first series as coach saw an influx of new blood with ten debutantes identified through those pathways, many of whom went on to become part of the core of the team for the next decade.

Former Origin players were brought in to instil and nurture the Maroons culture and history into new and current players alike and it was the legacy of these players that the Maroons were tasked with keeping. Darren Lockyer, already a veteran Maroon and then captain, has been quoted as saying that he never truly got origin until his time under Meninga.

However, Meninga also knew that to ensure Queensland’s culture never began to fade again it had to be enforced, players had to be held accountable on and off the field and no player was above the team.

A perfect example of this came after the 2009 series. After winning the first two games to take out a historic fourth series a number of players, including star half-back Johnathan Thurston were more focused on celebrating than preparation.

Thurston has since related how after losing the last game the then captain Lockyer let him have it for letting himself, his teammates and his state down and that from then on he had to take every chance he got to make things right. Even in a dead rubber after a record four series there was no room for complacency in the Queensland camp.

Incidentally, the next year was a Maroon whitewash. It wasn’t their culture that was winning games – that had existed while they were losing, it was how they used the culture they had developed over the years to shape their organisation and this cultural shift in the Maroons camp was an overwhelming success.

However, unlike in the formative years of Origin, The Blues response to the Maroons success compromised their own culture and in turn their ability to compete for their states pride. Their culture wasn’t dead, their players still bled Blue, but a culture built on success was starting to fade on the back of repeated defeats and infighting was starting to surface.

It took five years of defeats for the NSW establishment to decide that coaching NSW was a full-time role, at which point they began adopting many of the same systems that had helped the Maroons to success.

Their attempt at this approach was fundamentally flawed and often misapplied. You can’t just copy policies and systems that have been built around a culture that’s the polar opposite of your own and expect it to work.

A prime example is the way city-country gradually stopped being a legitimate selection trial in favour of a pick and stick policy.

The issue here is that for Queensland it’s not so much a policy as a necessity and in general is more a result of screening and priming players though the emerging squads to ensure their viability. It’s no coincidence that rookie players seem to fit into the Maroons team so effortlessly.

In a state with an abundance of quality players, sticking with certain players like Pearce, regardless of results just comes across as jobs for the boys, which hardly encourages others to engage in the competition for spots that once ensured their overall quality.

(AAP Image/Dave Hunt)

With the focus being on sticking with players, a chronic lack of accountability can begin to permeate the playing group and by extension the coaching staff which results in potential issues not being addressed when they do win and can manifest itself in poor on-field discipline when things don’t go their way.

Here’s the thing – sticking with players isn’t a bad idea, but each states reasoning behind doing so differs enormously. For Queensland, it’s a policy that’s been built around the culture they’ve created and is heavily reliant on the application of said culture to ensure that it doesn’t become a weakness.

NSW on the other hand simply adopted it because it seemed to work for Queensland, with no cultural backdrop to pin it on. They’ve slowly replaced the culture they enjoyed with a desperation for success that has lead to looking for quick fixes and shortcuts.

Despite all this, NSW has still proven that they have the ability to convincingly defeat Queensland. Through sheer ignorance to the issues holding them back, NSW has repeatedly stumbled onto the professionalism and accountability needed to get over this Maroon side, as evidenced by this series.

Unfortunately, also evidenced by this series is their inclination to slide back into detrimental habits learnt over this period. NSW saw Game 1 this year as the culmination of their plans to topple the Maroon juggernaut when it really should have been viewed as the spark to ignite their own cultural shift.

If NSW truly want to turn things around they need to go back to what their initial success was built on and the culture that enabled.

They need to start at the top and underpin every decision they make on the professionalism and accountability that once made the advantages they enjoyed a bridge too far for Queensland. When they look to what Meninga accomplished they should focus on emulating the processes that lead to the creation of the systems the Maroons enjoy rather then look to copy the systems themselves.

The Maroons culture isn’t inherently superior to the Blues’ culture, it’s simply different and NSW need to embrace that and build on it.

Culture doesn’t win games, but using it to focus your efforts is a massive advantage.

(AAP Image/Darren England)[/caption]

(AAP Image/Darren England)[/caption]