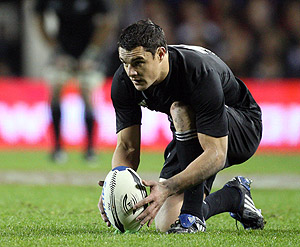

All Blacks five eighth Dan Carter lines up a kick at the goal during the Rugby Union Bledisloe Cup Australia v New Zealand rugby test match at Eden Park in Auckland, New Zealand, Saturday, August 2, 2008. AAP Image/Photosport, Andrew Cornaga

There has been an erudite and fascinating discussion taking place on The Roar about my use of the words ‘first five-eighths’ to describe the position on the rugby field of the player standing directly outside the halfback.

This discussion has encouraged me to write this article, setting out my thoughts on what should be the proper names for the positions on the rugby field.

First, though, the issue of the first five-eighths.

Several Roarers have suggested that if the term is to be used at all, it should be in the singular – five-eighth. Another point that has been made is that the term is a New Zealand usage and is not really applicable for the rest of the rugby world.

In matters like this, I invariably go to my bible: Keith Quinn’s ‘The Encyclopedia of World Rugby’ (ABC Books, 1993).

Quinn is a veteran and a most accomplished New Zealand rugby broadcaster and writer. He is a stickler for accuracy, as you can hear with his commentaries on the IRB Sevens, where he is precise in the pronunciations of the names of all the players.

The section in his Encyclopedia that is relevant is entitled: FIVE-EIGHTHS.

So my spelling is correct.

Quinn notes that this positional term is used almost exclusively in New Zealand. It originated with the 1903 All Black captain, Jimmy Duncan. In other countries, the terms are ‘stand-off’ ‘fly-half’ or ‘outside half.’

The point here is that most of the positional terms relate directly to some rugby theory.

With the five-eighths term, Quinn says that in the 1900s, the player furthest behind the forwards was the ‘fullback.’ Those halfway between were ‘halfbacks.’ The players between the halfbacks and the fullback were the ‘three-quarters.’

Duncan, according to Quinn, pulled a player from the forwards and stood him a little way from the halfback. This player could bring the ball back to the forwards, or pass it on to the three-quarters.

As the player and later players (under the two five-eighths system) stood between the halfway and the three-quarters, it was mathematically logical, Quinn suggests, to call the position the ‘five-eighths.’

In Australia, a different theory of linking the backs and forwards prevailed.

I call the theory, the 3 Fives: the tight five (props and second rowers), the linking five (the three loose forwards and two halves) and the attacking five (centres, wing and fullback).

These theories had an impact on how various positions were played.

In New Zealand, for instance, the running halfback of the Ken Catchpole, John Hipwell, Nick Farr-Jones and Will Genia style, is frowned on. Sid Going is about the only great New Zealand running halfback.

The typical great New Zealand halfback, like Chris Laidlaw or Dave Loveridge, is first and foremost a passer.

The New Zealand theory is that the two five-eighths set up the plays for the outside backs.

In Australia, Wales and South Africa, the two halves set up the plays for the outside backs.

Australia and South Africa tend to play an inside and outside centre system. There is little difference in the way the two positions are played. Both are running and tackling positions, rather than passing positions like the second five-eighths.

So Australia’s greatest inside centre Tim Horan (who was a poor passer, something the New Zealand system would not tolerate) played in much the same direct fashion as Australia’s greatest outside centre, Trevor Allan.

The Welsh/British centre system had further complication, which is now less frequently used, of pairing a particular centre with a particular wing, in a sort of left-centre and right-centre system.

When we get to the forwards, we find similar sorts of differences between the various countries.

Quinn, in his section on FLANKERS, talks about the New Zealand system of ‘blindside flanker’ who always packs on the narrow side and plays a ball-winning and tackling role, and the ‘openside flanker,’ generally a smaller, faster player who plays the role of the ‘fetcher,’ as the South Africans call the position, attacking the opposition halves and snaffling all the loose ball that is available.

The theoretical basis of this system was once described to me by Vince Paino, an old coach in Wellington, some decades ago: “The pace of the backs is the pace of the slowest back. The pace of the forwards is the pace of the fastest forward.”

There is a further complication in all of this, however.

Australia (before George Smith and Phil Waugh) and South Africa even today, play left and right flankers, rather like the left and right centres. It was extremely rare in South African rugby in the past for teams to have small, fast ‘fetchers.’

Even today, despite the advent of Heinrich Brussow (who plays a typical New Zealand openside flanker’s role), the Springboks will go into Tests with the massive, abrasive Shalk Burger or Juan Smith (great players, both of them) as their ‘fetcher’ flanker.

Because of this left and right flanker terminology and a traditional mindset about the need for a huge pack, the South African system does not encourage the development and selection of out-and-out fliers.

In Australia, the position which is called ‘lock’ in the rest of the rugby world is called the ‘second row.’ You will hear SANZAR referees (except the Australian referees) say to the packs as they get ready for a scrum: “Locks get down.”

Quinn says that the term ‘lock’ comes from the New Zealand 2-3-2 scrum, where the middle man in the scrum locked on to the two flankers.

The logical Australians seem to have applied the term – and this makes sense – to the last man in a 3-4-1 scrum, who ‘locks’ it together.

We are now in a position, I think, after this brief history, to have a go at answering the question that leads this article, and to set out the names that, in 2010, seem to be appropriate for the various positions in a rugby team.

The IRB in 1993, in fact, issued an edict setting out an international nomenclature: loose head prop, tight head prop, hooker: left lock, right lock: left flanker, right flanker: number 8: scrum half, fly half: left centre, right centre: right wing, left wing: fullback.

Some of these positional terms stand up. But some of them reflect an out-moded British nomenclature (as you’d expect from the IRB in 1993) that is not even used in British rugby circles these days.

Working from the props downwards, as it were, there is the question of ‘lock’ or ‘second row’.

As lock is used exclusively in South Africa, New Zealand and Britain, I think it should be the standard term.

The left and right flankers terminology is out-dated. The standard term should be openside flanker and blindside flanker, with an acknowledgment that in South Africa the openside flanker wears the number 6 jersey, unlike the rest of the world where he wears the number 7 jersey.

With the lock moving up in the scrum, as it were, the terminology of number 8 makes sense to me to replace the Australian ‘lock’ term.

The scrum half and fly half descriptions could be modernised to halfback and number 10.

I would point out that ‘Number 10’ is the title of a fascinating book about the history of great – number 10s – written by my favourite sports writer, The Guardian’s Frank Keating. Scrum half and fly half have a rah rah roar to them that is out of place in the era of professional rugby.

Number 10, like number 8, is a generic term that does not have baggage from the past.

It’s time, too, to drop the arcane New Zealand five-eighths nomenclature and replace it with the more modern inside and outside centre.

So, here is the Zavos rugby positions nomenclature: loose head prop, tight head prop: hooker: locks: blindside flanker, openside flanker: number 8: halfback: number 10: inside centre, outside centre: left winger, right winger: fullback.

But don’t hold me to this nomenclature.

I’m sure to lapse into old habits from time to time, a bit like a number 10 who is told not to kick but every now and again just boots the ball away out of habit.