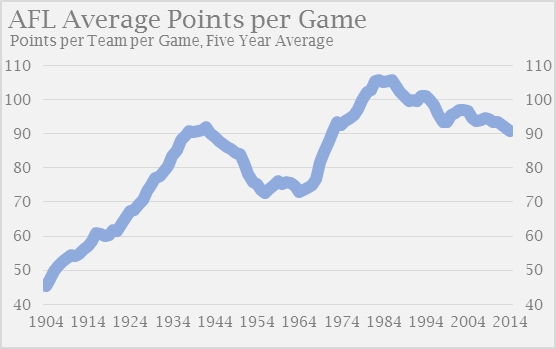

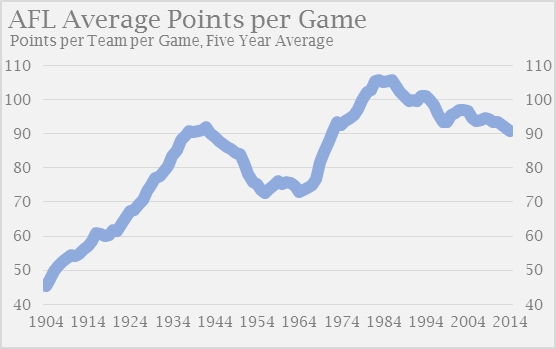

What would you say if you found out that last season saw the fewest points per game scored in the AFL since before man landed on the moon?

Bob Skilton – some say the game’s best ever player – was running around for some mob called South Melbourne. Carlton won the premiership, and there was not one, but two Carlton Mid subs available. But there was no interchange bench; that came in 1978. It was 1968, and in that season teams scored an average of 82.0 points per game in a 20 game season. In ’69, points per game jumped to 97.

Last year, the average AFL score was 86.9 points per game. Just to ram it home: that was the lowest since 1968.

It was one of the storylines of the year. Ugly Footy was in vogue. The punters were concerned there were more blowout games. Rolling mauls more suited to Brumbies and Waratahs were growing more common. There was speculation that umpires were granting fewer free kicks. But more than anything, it marked the continuation of a trend which gripped the AFL over the past decade – or more, if you believe the numbers.

Since peaking in 1987, the average points per game in the AFL has been on a tortuous decline.

Its difficult to pinpoint exactly what’s going on, but in more recent times an educated guess would suggest it is the influence of Paul Roos at the Sydney Swans upon his ascension to the throne in 2002. The Swans had, at the time, the ignominious honour of ‘longest premiership drought’ of active teams, if you include the years the team was based in South Melbourne.

Roos brought the concept of team defence to the AFL, and put hard work, selflessness and grit at the top of his list of recruitment priorities. Upon winning the Premiership in 2005, the brass at AFL House had the cojones to criticise the Swans’ playing style.

The Roos brand has taken hold amongst the AFL like a rouge passionfruit vine: Ross Lyon, John Longmire and Roos himself are head coaches in the AFL, while the game is populated by a plethora of assistant coaches that have ties to the ’05 Swans. Lyon in particular is known for a defence-first game style – more so at his previous head coaching position at St Kilda than at Fremantle – while Roos has presided over the two worst offensive seasons of any team in the past decade throughout his tenure at Melbourne.

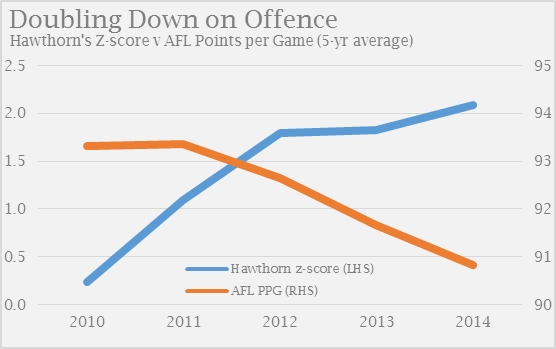

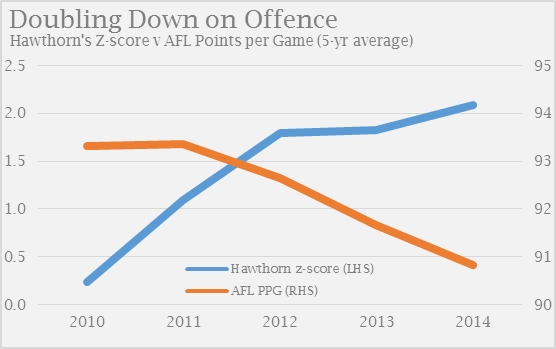

But defence is boring so lets change tact. If last season was the lowest scoring AFL season in ages, are we giving Hawthorn’s 2014 premiership, and their past few years of output, the right level of reverence?

Hawthorn: Doubling down on offence

Rather than follow the trend of putting defence first, Hawthorn’s scoring colossus hints that doubling down on offence may be the path to AFL success.

Everyone knows Hawthorn are a juggernaut. Since winning their 2008 Premiership, the Hawks have been at or near the top of the tree every season except 2009, and have made the top four in each of the past four seasons. Over that stretch, the brown and gold have recorded a z-score (head here for a primer) of +6.8, meaning their offensive output has been ranked first or second every year.

Sure, that’s impressive, but what’s even more impressive is Hawthorn’s z-score rating on offence has improved every single year since 2010, at a time where offensive output is becoming more and more difficult to generate across the AFL.

That’s not to say Hawthorn don’t have a sound back half of the ground – far from it. They ranked sixth in defensive points per game last year, and were around a goal a week better than average last year at that end. Alistair Clarkson’s Belichickian tactic of rushing behinds in the 2008 Grand Final (11 in total – almost one-in-five of Geelong’s inside 50s in the game ended in rushed behinds!) was the major contributing factor to the 2009 rushed behind rule change. But when you think Hawthorn, you think scoring.

Last season is a case in point. They lost one of the best offensive players of this generation, to their arch rivals no less, and were more potent scorers without him than with him.

Hawthorn kicked 367.256, for a crude accuracy rating (so, not including shots that missed everything – us mere mortals don’t get those numbers) of 59 per cent. If you take the finals out of the equation, the Hawks went just a shade under 61 per cent.

The Hawks kicked almost twice as many goals – no joke – as Melbourne (190). They were a full seven percentage points more accurate than the next best team, West Coast, but took almost five shots more per game than the AFL average (28.3 v 23.8). A z-score of +2.1 puts their 2014 season in the same league as Geelong’s run-and-gun machine during their premiership run.

Small tangent: Developing an Offensive Efficiency Rating

Check out some other relatively crude numbers for Hawthorn last year:

| Stat |

Hawthorn |

Average |

Hawthorn’s rank |

| Inside 50s |

55.4 |

50.2 |

#3 |

| Scoring Shots per Inside 50 |

0.495 |

0.461 |

#2 |

| Crude Accuracy |

60.70% |

53.80% |

#1 |

Each number tells a story. Not only did Hawthorn manage to get the ball inside 50 at a very good clip, once they got it in they scored just under half of the time. And when they scored, more often than not it was a goal. It’s useful, to be sure, but I’m not satisfied with useful.

What about if we tried to tell a single story instead?

Combining those three numbers in an equation, and regressing to the average across the AFL, yields what I’d like to call a team’s Offensive Efficiency Rating (OER).

This stat gets a team’s offensive output down to one number, combining its ability to get the ball into the scoring zone, its ability to score once there, and its crude expected points per scoring shot (again, unfortunately we can’t get numbers for out of bounds, smothered attempts and the like).

A contact in the AFL told me that around 85 per cent of scores happen from shots inside the 50-metre arc, and that over the long run no team shows an ability to consistently outperform or underperform in that metric.

Last season, Hawthorn’s OER came in at +29.7, implying Hawthorn were almost 30 per cent more potent than the average 2014 AFL offence. They were a clear first, too: second place went to Port Adelaide at +15.4, and Adelaide was in third at +14.8. Remember how I was jumping all over Melbourne? They came in, unsurprisingly, 18th at -29.5.

OER correlates perfectly with a team’s total points scored over the course of the year (a fancy way of saying it is essentially the same number presented a different way), but it gives us additional insight into a team’s scoring mechanics.

What leads to an above average AFL offence, statistically speaking? Is it the ability to get the ball inside 50 more often? Is it scoring accuracy? Is it finishing?

We can also use OER to answer predictive questions. For example, what if North Melbourne improved its goal-kicking accuracy to league average? (Its OER would improve from +6.8 to +8.8, lifting the Roos to fifth on the OER rankings last year).

It takes three numbers and gives us greater insights into one number, and helps us answer questions of both the quantity and quality of a team’s offence. When it comes to Hawthorn last season, there’s only one answer: why not both?

Hawthorn’s 2014 Grand Final opponent, Sydney, had an OER of +12.2. The Hawk’s demolition job of what was the second best team on the ladder showed just how significantly they are reshaping the offensive side of AFL football.

The zone offence: A case study

It’s the 13-minute mark of the first quarter, and Dan Hannebery has just missed a running goal. Grant Birchall kicks in to Jordan Lewis around 20 metres out to the right hand side of the goal square. Lewis looks up, and nothing is available – Hawthorn available, anyway – so he puts the ball to a pack on the skinny side wing as is the custom.

No one takes a mark, and Rhys Shaw picks up the spoil and hoiks the ball right into the danger zone: just inside the 50-metre arc, dead centre of the ground. Players converge from every angle, and there’s a clear view of Birchall setting himself to bring the ball to the deck.

Grant Birchall during Hawthorn’s 42-point win over Fremantle Dockers in Round 4 (Photo: Michael Willson/AFL Media).

To the right of my upscaled standard definition view of the game, you get just the smallest of glimpses as to what’s about to unfold. As 17 players converge on the danger zone, one slips to the fat side of the ground. We find out soon enough its Brad Hill making a break for it.

Birchall looks up, shielding his eyes from the blazing sun as he tracks the ball and surveys the scene. His team’s quarterback Luke Hodge gets to the attacking side of the forming pack – but on this occasion he’s not required.

After a tough spilled pack mark by Lance Franklin, Birchall brings the ball to ground, passing to Hodge as Hill makes his move.

Matt Spangher ends up with the ball, passing it to Ben Stratton who wheels about 90 degrees on his left, putting the ball about 10 metres ahead of the path of a now striding Hill, with Lewis Jetta in hot pursuit. As Bruce exclaims in his usual way, the camera pans to a ground level view of the action.

We expect Hill to blaze away and take Jetta on. Instead, Hill takes a step, and sells the deftest piece of candy. Jetta isn’t buying, but the ruse is enough to allow Hill the space to take half a step and get back to his preferred.

Some 40 metres ahead of the action, one of the best field kicks in the game, Matthew Suckling, has slipped his man as he leads out of the Hawthorn forward 50. Or so it seems.

Rewind back to the Shaw inside 50, and you can see a third man start running forward just as Hodge feeds the ball out to Spangher. It’s Suckling. Suckling takes the easiest of uncontested marks right on the tip of the centre square, looks up and sees a running Paul Puopolo.

The Nugget marks out in front, and kicks true.

The rest is history. Puopolo’s goal tied the scores at eight, where they remained until half way through the quarter. Scores again tie at 14. From then, Hawthorn add almost four points for every one Sydney manages to scrape together between just before quarter time and half way through the third, and the Grand Final is over.

In just over 14 seconds at that 13 minute mark, Hawthorn turned a 50:50 situation on the narrow side of the ground into what felt like a set play.

Except it wasn’t. It was one piece in Hawthorn’s Grand Final exhibit of the zone offence.

What does that mean? Well in the same way that Clarkson and Co. introduced the concept of zoning in defensive schemes in 2008, they have now thrown the traditional emphasis on structures on the offensive end out the window.

Their game is all about flexibility: one minute it’s Hill running on the wing, the next it’s a series of 15-metre chips, the next its a deliberate backwards chain of handballs to create a cross field uncontested marking opportunity. But it always ends the same way, with the ball in the hands of someone that can do damage within 80 metres of goal.

That 14-second stretch was repeated a number of times on the last Saturday in September: Hawthorn continued to push the ball, at every opportunity, to that 30-metre long zone just outside of the 50-metre arc.

From there, spaces were opened up inside 50 for just one or two players to lead into, with a third option – generally a tall and a couple of smaller blokes, perched in the goal square creating space. More often than not it’s a relatively short kick inside 50 to one of the three sharpshooters – although if you can’t kick you don’t play for Hawthorn so again it doesn’t really matter who’s on the end of it.

In cases where the defence flooded back, Hawthorn brings in the bodies and relies upon its surgical kicking skills to create set shot opportunities.

You hear coaches talk about the number of entries that get inside 30 metres as a benchmark. Hawthorn’s offence is built on using the whole 50-metre arc, and it’s a nightmare to contain. Everything is based on maximising percentages, and in my mind it’s why Hawthorn has been able to buck the low scoring trend that has taken hold in the AFL.

The Grand Final was a demolition job of the highest order (as fellow Roar expert Sarah Olle elegantly espoused last week), and the guy at the centre of that first decisive attacking blow, Hawks captain Luke Hodge was a deserved winner of the Norm Smith Medal.

The AFL’s first, and probably best, quarterback (a midfielder that generally plays just behind the contest, but that can play anywhere when required), imposed himself on the game, and personified the zone offence developed by Clarkson: 35 touches (including 21 kicks), 12 marks, four inside 50s, and a bunch of hit outs, spoils and a couple of goals for good measure.

In that 40-minute winning stretch, Hodge did it all, including beating Sydney’s only four quarter player, Franklin, in a deep one-on-one contest at the end of the first half.

It was a complete game – if such a thing exists in the AFL – and to me reopened the 2001 draft debate for the first time since Chris Judd’s move to Carlton.

Changing of the 2001 Draft guard?

We’re rapidly running out of inches, so I’ll skip the histrionics and move straight to the facts: who’s the best of the 2001 draft class is one of the AFL’s more hotly contested debates.

Luke Hodge was taken at number one in the 2001 AFL draft, with Luke Ball taken at two (by St Kilda) and Chris Judd’s at three (by West Coast). Talk about nailing your picks, guys.

For a long time it was a three-way contest, but over the years it became a dual between Hodge and Judd; and Judd is leading on points in the seventh round.

Two Brownlow medals, with different clubs, a premiership with West Coast early in his career, higher disposal average than the other two, more inside 50s, and highlight reels like this.

At the peak of his powers, Judd was without doubt the best midfielder in the competition, possessing a turn of speed and ability to break tackles that hadn’t really existed in the AFL before. His exit from West Coast kicked off a precipitous decline for the Eagles – although cultural problems did their part, too.

But Judd’s move to Carlton in 2008 hasn’t proved as lucrative, and it’s all but guaranteed Judd will end his career without adding to his premiership tally. The Blues peaked in 2011, and have put together three middling seasons since; Cam Rose reckons middling is best case scenario this season, and I agree with him.

Judd’s last few years have been wrecked by injuries, which have seen his statistical output dwindle to that of a role player, rather than the unstoppable force he had been in earlier years. And that, friends, is why I think it’s time to reopen the debate.

Luke Hodge has maintained his output over the years, while the scheme and role he plays in has made him an increasingly effective player. He’s been central to three premierships in the time since Judd’s last, and won two Norm Smith medals seven seasons apart for good measure. Last season, Hodge put up his best year of disposals and marks, and amongst his best inside 50 tally.

Hawthorn’s zone offence scheme, which places emphasis on outside running, kicking for advantage and ensuring the team takes the most efficient path to goal, has seen Hodge evolve into an undisputed champion of the game as his career has progressed.

Carlton’s focus on the old way has contributed to Judd’s move from demigod – one of the best ever – to merely an undisputed champion. In this respect, I think it’s time Judd vs Hodge was settled more in favour of the two’s original draft order; with Ball a close(ish) third.

Can anyone challenge, or emulate, Hawthorn in 2015?

Well that was a fun tangent, but back to the real stuff: is Hawthorn’s scheme strong enough to stand the test of time? And are there any teams that can challenge them this season?

Football is constantly evolving. Just think back to Geelong’s premiership run for a proof point. Mark Thompson had Geelong playing a run-and-gun offence built on speed, quick ball movement, and the handball – the Cats executed five freaking thousand handballs in 2008, around 40 more per game than the next most handball happy side that year and a ridiculous 80 more than average.

The West Coast-Sydney rivalry is another point in the game’s evolution. Pagan’s paddock. The flood. Zones. Torps. One of the AFL’s most endearing characteristics is it isn’t static.

So it’s fair to assume there’ll be some catch up over the coming seasons. Are there any other standout candidates?

The fact of the matter is Hawthorn have built something most sides will find it really challenging to emulate. Of last year’s top eight, you’d argue the Dockers and Sydney place emphasis on the Roos model, with a few tweaks.

Geelong pursue the Geelong model, although have reduced their handball use to something closer to average.

The Roos are doing their own thing that doesn’t quite meet the same offensive level of the Hawks, but that also doesn’t quite match the hardness of your Swans and Dockers-type line ups.

And we know what the yellow and black are shooting for.

Port Adelaide come to mind, but they are less polish and more grunt. And motivation.

Astute readers will note the missing team: The Essendon Bombers.

Essendon were 12th on the points for ladder last season with a top four defence (yes that’s right) leading them to 12 wins and a ninth-placed ranking on the simple ratings system I introduced last week. The Bombers were also first in total kicks (225.0) and second on kicking differential (+21.0) – Hawthorn was second and first, respectively.

Now, everything Essendon comes with a whopping big asterisk right now, but of all of last year’s top eight sides the Bombers look the most Hawthorn-like.

Not necessarily in game style – Mark Thompson brought an added element of running play to the team last year, and it worked – but in personnel. Essendon have been one of the more active sides in free agency since its introduction, adding Brendon Goddard, Paul Chapman and Adam Cooney in each of the past three years. Goddard was the most astute addition: he’s Essendon’s quarterback. Chapman gives them forward half nous, and Cooney will do the same.

Their 10-man engine room is full of big bodies, led by Brownlow medallist Jobe Watson. Their ball users are dynamic, perhaps not quite as dynamic as Hawthorn, although I’d take Dyson Heppell over most in the Brown and Gold.

The loss of Patrick Ryder really hasn’t been given the attention it deserves (although it’s hard to top the number one story at Essendon), and the Bombers will be looking for Joe Daniher to take a giant leap this season. It might be a little bit of a stretch, but Essendon have the cattle to play the Hawthorn brand should they wish.

Despite all of this, Essendon had an offensive efficiency rating of -3.7 last year. This ranked 12th, and was owing to the Bombers’ below average scoring rate per inside 50 and crude scoring accuracy.

There’s a reason why Hawthorn are Hawthorn, and everyone else isn’t. Playing Hawks footy isn’t easy, and it’s why Hawthorn are deserved flag favourites for season 2015.