So posits ‘The Broarzilian’ – Tim Barnett during regular proceedings – in this inaugural piece of his furious, spurious World Cup series.

We scan our calendars to find those hallowed places: where sport and synonymy mix. We relish a British Open from St Andrew’s, a Cup final live from Wembley, or a world championship darts final shot at Winter Gardens, nudging Blackpool Pier.

So we’re entitled to be giddy, because we contemplate the richest connotation of them all. Humanity hasn’t devised any more synonymous exhibition than a football World Cup in Brazil. Not the round-ball coming home, perhaps; but when it goes the place where everybody knows its name.

Contrive any mind game you may (bring your apitos if you must) – just get your head there – because Christ the Redeemer’s on it; squirming with desire and squinting at the ready.

Albeit he depicts a demonstrably stoic fellow; one hopes South America’s textile magnates have weaved up a size-appropriate hanky as contingency. Because whatever conventional discourse, jaded punditry, or your favourite amenable bookmaker might infer, he’s bound to need it. The Redeemed Ones will not produce a series denotable by triumph. And there are holes that ought be picked; starting at the back.

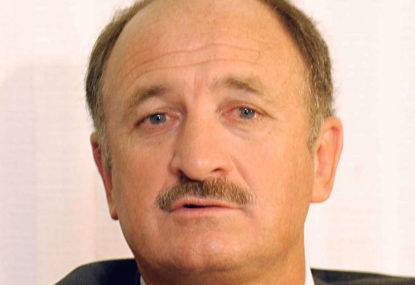

Brazilian boss Luiz Felipe ‘Big Phil’ Scolari looks set to stick Julio Cesar amidst the onion bag; furnishing the veteran stopper with the loyalty he might expect. But Cesar presents with a recent career trajectory to render Meatloaf ebullient.

To survey his last four seasons – between posts and atop benches – is to contemplate an ordeal; from Inter Milan and glove-flapping culpability for Brazil’s World Cup 2010 quarter-final loss via West London to Toronto in exile.

That’s ‘West London’ as in Queen’s Park Rangers (not Chelsea), and that’s Toronto as in the MLS frontier franchise peddling the soccer gospel to North American heathens.

But Cesar’s evangelism is the furtive sermon of the missionary yearning elsewhere’s plusher carpets. The shot-shopper resorted to Canada in February 2014 as a QPR loanee: following the profligate Londoners’ Premier League relegation and his personal version to the League Championship’s spartan benches. Even unconverted North Americans realise there’s only room for one ‘goal-tender’ in a team, and it wasn’t Julio Cesar.

That A Selecao’s primary custodian confronts a native World Cup campaign after his South African trauma, 2011 Copa America ignominy, and twitchy afternoons sidelined in Doncaster and Barnsley disaffects nearly all except Scolari; who has proffered his anointment.

Big Phil would know he’s potentially one glove-flap away from an exigent dilemma; with Botofago’s popularly-endorsed Jefferson busting bladders for inclusion. Either way, the onion bag seems accessible.

Notwithstanding the keeper conundrum, Scolari’s duress remains in calibrating a midfield battery stacked with commercial endeavour and disparate stars. His critics can’t cite indecision – one wouldn’t omit ex-lynchpin Kaka, PSG’s Lucas Moura or Liverpool pair Lucas Leiva and Coutinho without clarity of purpose – but the reticence remains. Reckoning with his second stint in command, Big Phil could testify as to a Brazilian coach’s untenable drama; to produce teams that swagger and succeed, that dance, beautify and punish.

Theirs is a footballing culture to mock professional sport’s furtive notions of result-based practice and unconditional victory. Winning ugly isn’t an option; but Scolari’s preferred configuration offers functionality before fantasy.

A holding compact of Tottenham’s Paulinho and Wolfsburg workhorse Luiz Gustavo (or Manchester City’s Fernandinho) should operate behind Chelsea charmer Oscar – who seemed trammeled toward the end of an arduous club campaign under (Blues manager) Jose Mourinho’s auspices. The whizkid’s credentials survive any cheapjack dissection – he’s quick, dual-footed, technically pure and industrious – but Brazilian World Cup campaigns have failed behind superior creative facilities.

And the alternatives don’t beguile. Chelsea’s box-to-boxers Ramires and Willian prosecute game-plans more often than they tear teams asunder, and Inter Milan’s Hernanes might lack the requisite esteem to earn Scolari’s commission. Comparisons to Canarinho midfields-past – steered by Gerson, Socrates, Zico or Dunga – or the potent adaptability as supplied by Germany, France, or class-littered Spain don’t bear generosity.

Whatever they design implicates Neymar, the Barcelona starlet tipped by the mould that’s begat every native striker-superstar since Pele. The preposterous narrative that is a Brazilian World Cup edition pegs him more than anyone. Not that he seems reluctant: Kanye West would sneaker-gaze his way through an audience with the menino.

But consider the terms by which he swans upon his platform.

Scolari typically deploys him in an interchangeable wide role – with license to maraud and centralise – relying on his speed and service as well as his goals. Ostensible target-man Fred will deflect traffic into his (and counteractive attacker Hulk’s) path all day, but the gaffer expects reciprocation whenever possible. And critically, Big Phil’s uncomfortable shifts have occurred when Neymar has shirked the extent of his task; opting for mazy, vanity-stricken channels unto the goal box instead of touchline occupation.

Notwithstanding the overlapped terror meted out by fullbacks Dani Alves and Marcelo, the prodigy owes collaborative width to a system readily diffused without it. Brazil will lean upon his aptitudes, but Neymar is a sponsor to conflict: between a whiteboard’s imprimatur and the samba drums’ lascivious throb, impelled through nationally-collected lust as they are.

Popular appraisal has him lashing miracles as they swoon by installment – just as Ademir, Pele, Romario and Ronaldo supplied them – and he will be desperate to oblige. But Scolari’s is his prerogative. Although history records twenty-two year-olds reckoning with more, Neymar’s suitability for task cannot be presumed.

And what of the arena. Upon the relevant final whistle – and cessation of the throbbing – reviews might avoid pitch-bound dissertation altogether. Brazil is aching, and seminal voices cite globalised economic imperatives for the poverty and deprivation millions placate by love of football.

To kick and dance favela life away is one thing – thwarting societal disintegration as soccer has and does – but to convince FIFA to set its gluttonous banquet amidst the indigence is another. Lethal steel glistens upon every civic space and boulevard by founded reason. The dissidence is nascent, sincere, and recorded with conviction: it deems football’s governing body as rapacious as any neo-liberal, pan-global entity presenting itself for plunder and the domestic government like so many craven curs.

Protestors will make their message throughout – and the Brazilian national team, replete with its absconded, commercially-saturated, hyper-celebrities – is as odious a brand as FIFA’s sundry corporate partners. The fulmination is for anyone they suspect unavailable for post-carnival clean-up duty; and the IOC will know the experience before flame kisses cauldron for Rio de Janeiro’s 2016 Olympics.

But that will seem like fury distilled. Because this is a football World Cup: acquitted by competition, infused by essence. Brazil doesn’t concede dominion; they merely let it out; and orthodoxy ought resume under Christ the Redeemer’s nose. However. There are Julio Cesar’s capricious gloves, a discernible midfield, and the volition of an arrogant tournament-debutante to survive and overcome. And then there’s the party host; crying by the punch.

Good luck, ‘Phil’ Scolari.

The Broarzilian bought the Jules Rimet Trophy at an Ipswich garage sale in 1989, snipping change from a twenty. He wears a Jorge Campos-signed Mexican national goalkeeper’s jersey as a pyjama top. In addition, he regularly emulates Gheorghe Hagi’s 1994 World Cup goal versus Colombia in his back yard, except for the part in which the ball hits a designated target.