Sometimes a game of footy is more remarkable for how one team lost it than how the other team won it.

And Friday night at the MCG is about as textbook an example as you will find.

Melbourne, for the second final in a row, were the better team for the majority of their semi final against Carlton. Yet for the second week in a row, and the fourth final in succession since their 2021 premiership, they have had their hearts broken and dreams dashed on the big stage in utterly brutal fashion.

This week wasn’t down to wayward kicking inside 50 to wreck general dominance in every other area – nothing so trivial as that. This was a case study in a team shooting itself in the foot so many times that by the final siren there were no toes left to blow to kingdom come.

It was Kysaiah Pickett giving up a shot at goal with the dumbest of free kick reversals in the first quarter – how the Demons would love that shot now? It was in the countless silly 50m penalties committed to give the Blues free access out of their defensive half without a struggle. It was in the reprehensible kicking for goal once again, particularly from within 30 metres of the big sticks, where a scoreline of 4.6 brought the lion’s share of the pain of their 9.17 final scoreline.

Most of all, it was in the final five minutes when, despite all of those previous disasters, it looked like the Demons, through sheer force of will and the magnificence of Steven May, had still done enough to stave off a Blues team that looked for all money down for the count.

Enter Max Gawn for the first: with Clayton Oliver going for broke with a set shot from outside 50, it wasn’t a Blue set of fingers getting the decisive touch to the ball, but rather his own skipper thwarting what would have been the clutchest of sealing goals.

To be fair to Gawn, at least he flew for the ball. It was baffling to see Bayley Fritsch actually walk out of the goalsquare as the ball was coming in; it was his man, Brodie Kemp, who leapt from the side and must have spooked Gawn enough for him to try and keep it alive rather than merely body Weitering away.

Fritsch, as well as Joel Smith, watch harmlessly from close range as Oliver’s kick carries right to the goal line: get both of them to the ball and doing their job of bodying their defenders away, and it probably gets home.

Still, for all that, Pickett’s blunder a few minutes later may have been even worse.

Kozzie had had the most fascinating way: he produced about 40 per cent of the Dees’ dumb stuff, with two 50m penalties for encroaching into the protected area, that free kick reversal for jumper-punching Mitch McGovern, some poor set-shot kicking, and a high bump on Cripps that would have cost him a preliminary final even if the Dees had held on.

But his move to being the deepest man in attack was a masterstroke by Simon Goodwin, both in getting his danger at ground level as close to goal as possible, while also removing at a stroke his tendency to cheat by calling for the ball running back towards goal from higher up the ground rather than leading back up at the footy.

Anyway, with two minutes and 17 seconds on the clock, Pickett equals a one-on-one contest with Alex Cincotta, is first up and to it, and gets as his reward the most precious commodity of all in a final: a second of time.

Three metres clear of Cincotta, on the half-forward flank, Pickett has two options: he can spin around and handpass to Christian Petracca, screaming for the footy just behind him in equal amounts of space, with a raking right foot perfectly suited to the occasion.

Or, even better, he has Ed Langdon all by himself running towards goal: turn into space, and Pickett has more than enough skill to find him, with the Blues’ deepest defender in Adam Saad a long way off.

He does neither. Without even looking inboard, Pickett chooses the third of two options: on his non-preferred foot, still going towards the boundary line, he snaps over his shoulder, his only thought for the big sticks.

Pickett is skilled enough that the snap comes close enough to be denied by the post, but it was still a horrible, low-percentage decision with two infinitely better options there for the taking. If he passes to Langdon, not only does the wingman have a shot from 20 metres out with little angle to speak of – yes, that’s still danger given the way the Dees kicked all night – but a guaranteed extra 30 seconds off the clock.

Still, the Dees should have been saved by their defence. When Jake Lever, with 100 seconds left on the clock, takes his sixth and most significant intercept mark at half-back, moments after a superb spoil to defuse another dangerous situation, they should have been able to negotiate the final stages.

They’d take less than 30 seconds to blow it.

Lever, unlike most of his teammates in those fateful final minutes, does everything right: he takes his full time, goes as long as he can, and as close to the boundary as is feasibly possible without sacrificing territory.

But the structure he is kicking to is horribly flawed.

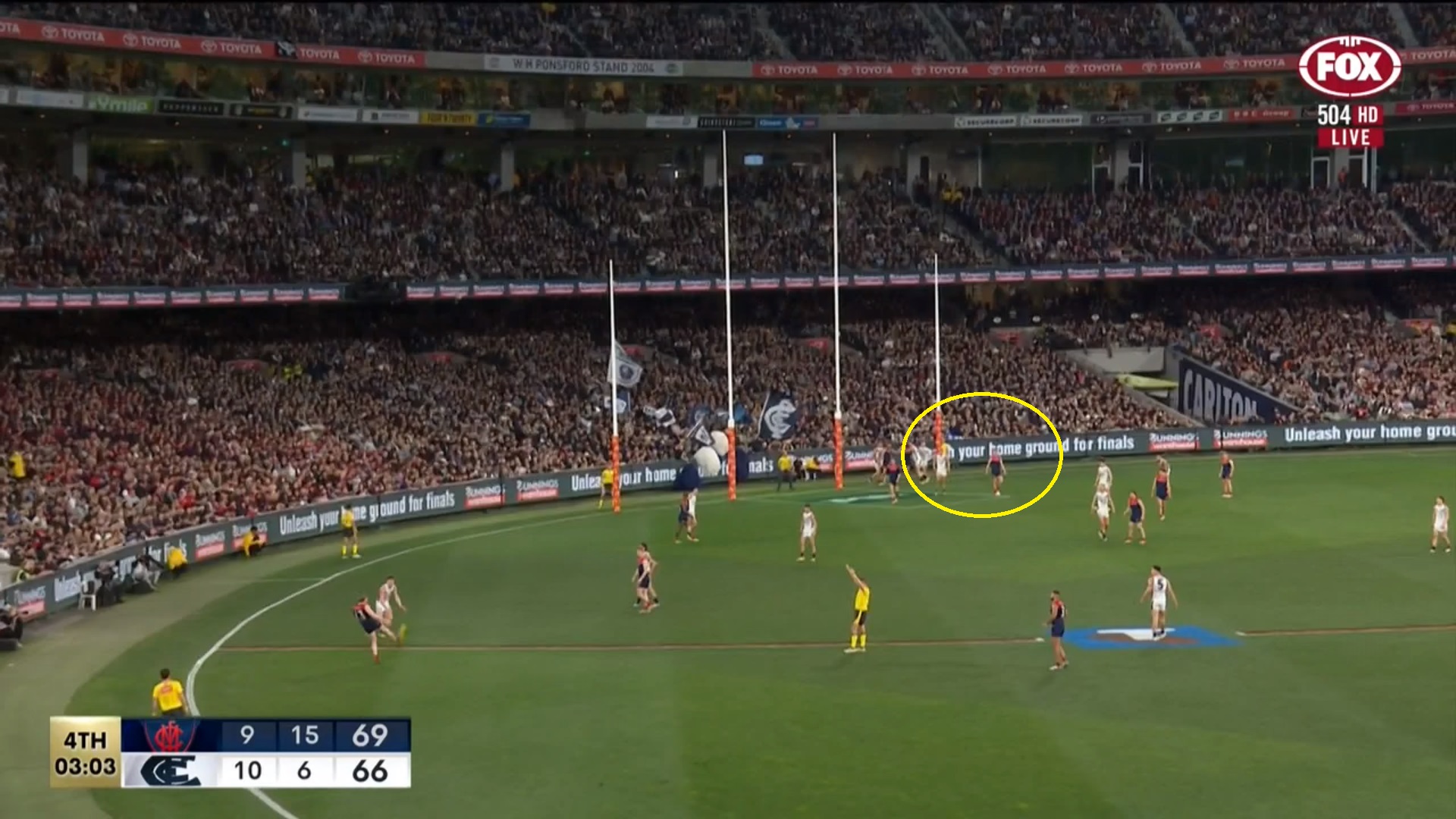

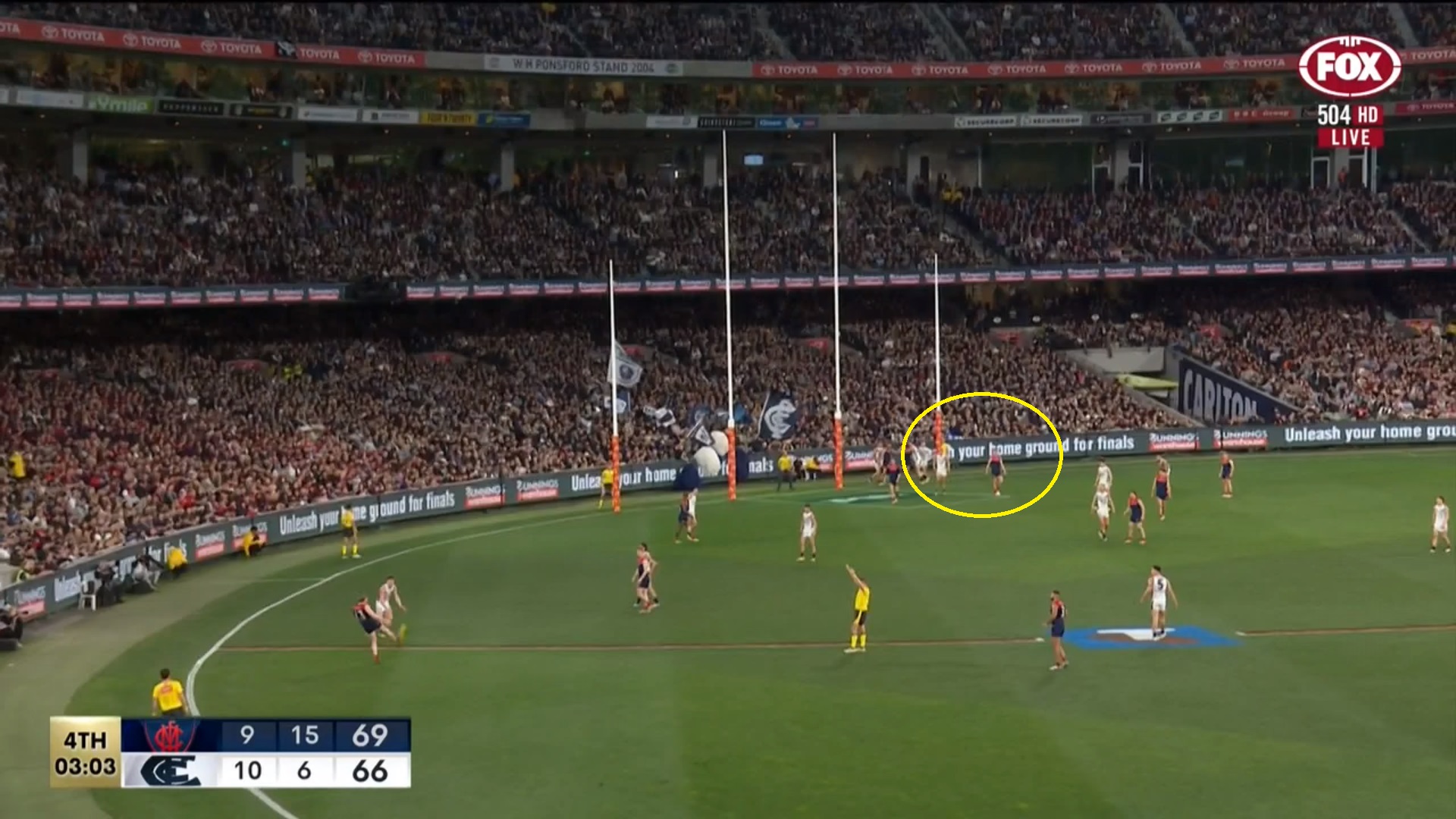

The two major issues are this: Gawn, whether knackered or not switched on, is caught woefully out of position – inexcusable given how long Lever took to soak up time after his mark – and as a consequence doesn’t even reach the contest. He’s the Demons’ best contested mark by a street: if he takes a big grab there or even gets enough hands on the ball to force it over the boundary line, they win the match.

The other issue is, just behind him, the Blues have their extra man – Fritsch has been moved as the loose behind the ball – into the centre corridor. They must roll the dice, and they know it.

Considering no Gawn, it’s a minor miracle that the Dees both bring the ball to ground and win the loose footy when it gets there; that, too, should have been enough. Jack Viney, wonderful all evening, bounces off a tired Cripps and into a fraction of space: the Dees have the footy, and with it surely territory to follow.

Except Viney, a left-footer, is tired enough and unrefined enough on his non-preferred to make the mistake that begins the flow of bloopers: he snaps on the run, and can’t clear Weitering, all of 15 metres away.

It’s the most excusable of the Demons’ howlers in those final five minutes – it’s the only one which is a proper error of skill rather than thinking – but it throws up all manner of possibilities. Why didn’t Viney handball to Petracca, once again ignored despite being in space just next to him, and on his right side to boot? Why did Viney look to screw the ball back inboard, rather than hoofing it as far as he possibly could?

For whatever reason, as soon as Viney gives the ball up, the Demons are in serious trouble. With eyes only for the corridor, Weitering looks up… and sees two Blues by themselves in there, the one loose from before and an extra who has held his space when his Demons opponent – I think Kade Chandler? – sucked in too close to the previous contest.

It causes chaos, and the beginning of an overlap that would take the Blues to the match-winning goal. Lachie Hunter needs to leave Sam Docherty, who he’d been guarding throughout that play, to stop Ollie Hollands from marking and using that outnumber to go straight up the guts. It leaves Docherty free, but at least Hunter’s intervention has forced him wider.

Then Judd McVee makes another howler: he has had a great debut season, but showed all the inexperience of one so young with how he approached the next contest.

Hunter, five seconds earlier, had done what McVee should have: seconds before Hollands’ mark, he had decelerated, enabling him to stand the mark rather than go flying past, forcing Hollands to go back (or in this case, across) and take his kick.

McVee doesn’t do this. With all the enthusiasm of youth, he sprints for the free Docherty, arm outstretched for the game-saving spoil… and arrives a second too late. Worse still, he has committed the cardinal sin in such a situation – he has failed to take any body at all with his spoil, and in so doing both taken himself out of the contest and left Docherty free to run on.

If McVee finds body, or slows up beforehand to guard the mark, then Docherty’s kick comes from 85 metres out rather than 60.

It’s the difference between exploiting a Demons backline that has somehow fallen to pieces, and being unable to clear May in the first place.

Because May, and Lever too, have set up assuming that’s how far Docherty will be kicking from. The moment McVee overcommits, instead of having a precious extra second to set up, steel himself, judge the ball in flight and take another colossal intercept, May is found caught in no-man’s land at half-forward: not close enough to Docherty to smother or stop him getting within 60 to kick, which is what he must do when it becomes clear no other Demon will get to him, and not far back enough to help what comes next.

Docherty’s kick clears five Demons, and it becomes clear in mid-air that something has gone horribly, horribly wrong. With 66 seconds on the clock (an appropriate number, as it would prove), it becomes clear that the Blues have a dream scenario: an extra player, free, in the goalsquare.

God knows how Blake Acres found himself as that man – with shoulder buggered, he had unsuccessfully tried to smother the Lever kick that started this whole chaos, and it seems he took a risk by running back to the goalsquare, probably as soon as Weitering intercepted.

Whatever the case, the tired legs of Alex Neal-Bullen and Ed Langdon, both present for that fateful stoppage on the wing when Viney turned it over, have only carried them to the 50m arc, a good 30 metres from Acres, by the time he marks.

Through all this, it becomes painfully clear that Gawn is knackered: as the play continues, the Dees’ best bailout option to guard space in defence is stuck, walking slowly along the wing, with the Dees’ defensive 50 wide open. Had he found the strength to get back there, Acres would surely not have marked.

Honestly, the most appropriate reflection of this game was that Acres stuffed up as well: from 15 metres out with little angle to speak of, the set shot was simple, and he had the chance to, with 62 seconds left, wipe half of them or more off the clock by going back to take his kick.

He plays on, and very nearly enters the eternal Hall of Shame by scuffing the dribble kick and almost hitting the post. He doesn’t, though. Only one team would butcher this match.

And just to add one final lashing of disaster to the piece, with 25 seconds to go, the Dees win back possession from the last ball-up of the game. McVee goes inboard to Tom Sparrow, just on the Blues’ side of the centre, and needing to go straightaway and as long as he can.

He makes to go sideways to open up the corridor, sees Tom De Koning bearing down on him from behind, hesitates, and in that fraction of a second lets Adam Cerra close enough to make the smother that would cruel their last chance.

That’s how you lose a semi final. That’s how you blow up a premiership campaign.

That’s how you piss a season down the drain.