Nicholas Stöckling

new author

Roar Rookie

Fellow Aussie-Croat Zeljko ‘Spider’ Kalac bluntly summed up his long-time friend’s predicament: “There was no way you could say no, mate.”

Viduka’s prodigious skill and absurd goal tally had reverberated back to his parents’ homeland.

Here was a child of Croatia worth claiming. His reputation with Melbourne Croatia in the National Soccer League (NSL) was such that in 1995 the founding Croatian President, Franjo Tuđman, came literally knocking on his door for a meeting at the Viduka household.

Nationalistic spirit imbued, patriotic obligations detailed and the most sought-after player in Australia was signing for Dinamo Zagreb in barely post-war Yugoslavia. A proud son of Croatian immigrant parents, Viduka clearly felt familial and community pressure to sign for this nascent club.

The integral role ‘ethnic’ clubs such as Melbourne Croatia played in introducing and accepting post-war immigrants into the Australian bubbling melting pot was crucial for recent arrivals like the Vidukas.

Football was the focal point for the diaspora. Fundamental in acclimatising Croatians, Greeks, Italians, Serbs, Jews, Hungarians and many other communities into their new homeland. These were the vital lifelines to the old country for generations of Australians.

Indeed, Viduka’s deep affection for Melbourne Croatia and his joy in representing his Croatian heritage on the pitch is a lingering memory for those who witnessed his early exploits. This was his club. He belonged. And prospered.

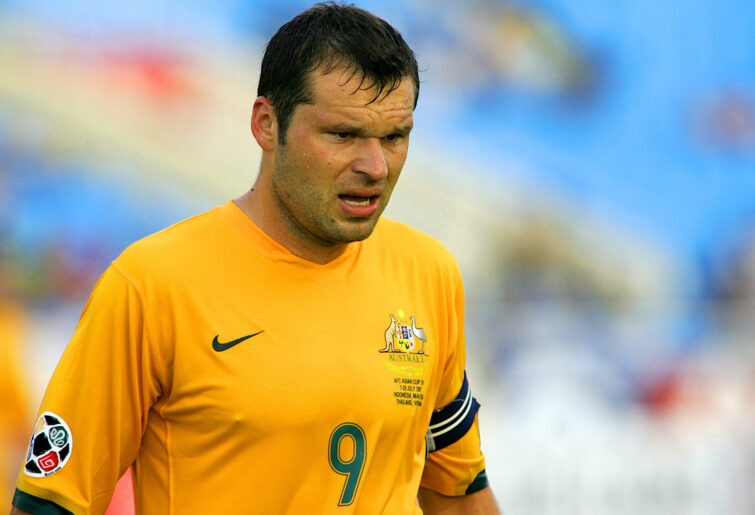

(Photo by Koji Watanabe/Getty Images)

NSL Player of the Year. Young Player of the Year. Top goal-scorer. Twice. In his first two seasons.

Never before in Aussie soccer had a young man shown so quickly just how much better he was than those around him.

He was already a complete player. This led to an agent feeding frenzy in Melbourne’s Sunshine North. This frenzy also followed him when he represented the Young Socceroos abroad.

The question was: should he move to Europe now or last week?

Those who witnessed the stunning arrival of the teenage big man, with the footballing intelligence and skillset laughingly beyond his years, were not surprised that his time in Oz was up.

His choice of destination, while understandable, was nonetheless at a lower level than many had hoped or envisaged.

Borussia Dortmund beckoned. Offers came from Spanish giants. Yet it wasn’t the Bundesliga, nor La Liga. His next move was to the Croatian first division. The Prva HNL. The Viduka family’s roots dug deep.

A new country and, yes, in many ways a new culture greeted Viduka when he landed in Zagreb. Immediately and correctly the President claimed credit for the signing. The rise continued. More stunning goals, celebrated in the same manner with a kiss on the same Croatian flag emblem, albeit on a different shirt.

Dinamo Zagreb 5, Partizan 0. UEFA Cup runs, Champions League matches. Three doubles in three years. A goal every two games. Best ‘foreign player’ in the national league.

The intimate connection between politics and football is well understood. It is, however, difficult to imagine a country or a time where the two were more symbiotic. The birth of Croatia as a nation is intrinsically attached to football.

Players were seen by some as representative soldiers for a burgeoning Croatia. Boban’s jump kick on police is said to have ignited the war of independence and has entered nationalistic folklore. Football is integral to the Croatian story.

Stadiums are often where minorities beckon nationhood. Where cultural songs, freedom of expression and patriotic instincts find their voice. This was undoubtedly the case with Dinamo Zagreb in communist Yugoslavia. A place where patriotism and culture merged with war memorial. Potent and combustible.

Such was the climate that the young man from suburban Melbourne found himself in. He was barely 20. Yet he was now a symbol. A figurehead in a deeply complex time. Viduka has since stated he was not at all prepared for war-ravaged Zagreb.

This was a land of profound hope and deep trauma.

Viduka was Tuđman’s boy. Linked and forever connected to the President. Thus, the President’s continued popularity was essential for Viduka’s acceptance and support in the stands.

As the Bad Blue Boys Ultras’ support for Tuđman gradually dissipated the cheering for Viduka also subsided. Then the hostility began. Those associated with the President began to feel this dissent. On the pitch, for Dinamo fans, Viduka became an outlet upon whom they could vent their anger.

The raw reality of politics’ deep influence in football became evident to Viduka towards the back end of the 1997-98 season.

On the pitch he continued to perform. Scoring both goals in the flare-illuminated smoke of the eternal derby against Hajduk Split. He remained the focal point of the attack. Battering headers amongst balloretic pivots. But it wasn’t enough to assuage the fanatics.

His was a burden too heavy to remove. He was too closely aligned with the President.

The chorus of insults, savage and direct, started to follow him away from the Maksimir, Dinamo’s home ground. The weight of his association to the President was such that the vitriol became contagious.

Away matches offered no respite. Despite an irresistible goal-scoring performance at the Stadion Poljud (Hadjuk’s home), the entire stadium, home and away fans, taunted the young Viduka.

“President’s pet, president’s pet”.

The chant that had hitherto been heard only in home matches, now menacingly sounded also on the team’s travels. Uniting enemies in collective song.

His race was run. His return to his parents’ homeland was over. For now. His decision to leave brought with it more angst. Hatred, in fact. His car was vandalised. He was spat on in the street.

Keeping the oldies happy and returning to his roots at the behest of his people’s first President changed him. A country transitioning from communism to democracy transformed the carefree boy into a wary adult.

He was now a hardened professional who had revelled in the utter adulation of the most zealous of fans. But the acclamation was over. The dream had soured.

The deep personal impact of the gradual loss of support along with the subsequent malice came to a

effect all facets of his life in Zagreb. He had no choice but to go.

As Viduka himself succinctly concludes, “It wasn’t football, it was politics.”