Aussies leapfrog India in rankings despite neither team playing, Starc returns to form in IPL

Australia have reclaimed top spot in the ICC's Test rankings, replacing India. Despite not playing since winning 2-0 in New Zealand in March, Pat…

Sponsored

Anyone who’s played any level of sport knows at least one of them. Someone who’s a lovely person off the field, but as soon as they step onto it, it’s another matter entirely.

For all its reputation as the gentleman’s game, cricket is full of notable characters who regularly caught a healthy dose of white-line fever.

Here, in no particular, are three notable ones to hail from these shores.

Mitchell Johnson

Who better to start with than Mitchell Johnson? The mild-mannered, affable commentary you’ll hear him contributing on the radio these days is a far cry from the fearsome fast bowler whose bowling was so terrifying it ended careers.

The 2013-14 Ashes will always be remembered as Johnson’s series, and not just for the 37 wickets at an average of under 14. Although they were pretty damn good.

No, it is the manner in which the then-moustached left-armer bowled. Having previously been thrown into international cricket purgatory, then sidelined further by a toe injury, Johnson returned to Ashes cricket with a display of menacing pace.

Used perfectly by captain Michael Clarke in short, sharp spells, Johnson was able to clock 150 km/h with alarming frequency, and at great accuracy. At such speed, his bouncer was lethal, and left some of England’s finest batsmen with scars both physical and mental.

“I felt I was being questioned as a man,” Johnathan Trott – who’d scored a lazy 445 runs at 89 on his previous trip to Australia – recalled. “I felt my dignity was being stripped away with every short ball I ducked or parried. It was degrading. It was agony.”

Kevin Pietersen was of much the same frame of mind, even if he put it a little less eloquently in his autobiography.

“Lunch? No thanks. I was sitting there thinking, I could die here in the f—ing Gabbatoir. How could Trotty, this calm, collected mate of mine, play like that? Get hit like that? Get out like that? I was petrified.”

Trott pulled out of the tour straight after the first Test due to a stress-related illness. Off-spinner Graeme Swann retired from international cricket after the third. Stuart Broad almost had his foot broken by a Johnson yorker. Pietersen played his last-ever Test that series.

And it wasn’t just England who the Queenslander picked on. Just ask former South Africa captain Graeme Smith, who had his hand broken by Johnson twice in one series.

(Photo by Robert Prezioso/Getty Images)

Dennis Lillee

From one quick to the next, Dennis Lillee was for so many years the Australian fast bowler.

A terrible back injury which almost ended his career prematurely forced him to embrace a more guileful, crafty approach in his later years, but when he first emerged in the early 1970s, Lillee was a nasty prospect for opposing batsmen – even one as exceptional as Sir Garfield Sobers.

The West Indian legend, the greatest all-rounder in cricket history and one of the finest ever left-handed batsmen, had the unenviable task of facing off against a young Lillee for the World XI in 1972. In the second ‘Test’ (technically just a first-class game), he lasted two balls, as the Western Australian picked up career-best figures of 8-29. The next match, he was gone first ball.

Lillee, however, had drawn Sobers’ ire.

“Every time I walked into bat, Dennis seemed to present me with these short-pitched deliveries. And I was getting a little bit fed up of it,” Sobers said in the wonderful Cricket in the ’70s documentary.

“I went in the dressing room that evening to sit next to Ian [Chappell]. I went to carry a message so that Dennis could hear.

“So I sat next to Ian and I said ‘Ian, you got a man in here called Lillee.’ You know, I was getting back to the old days when they used to call cricketers by their surname.

“I said ‘You got a man in here called Lillee, and every time I got into bat I seem to be getting these short-pitched deliveries. I just want you to tell him, or to let him know, that I can bowl short, I can bowl quick, and I can bowl bouncers too. So he better watch out.'”

Dennis Lillee: so good he was given a statue. (Image: Flickr/zoonabar CC BY-SA 2.0)

As Chappell said, irritating one of cricket’s greatest ever players wasn’t the brightest idea. Lillee was duly bounced out by Sobers when he batted next, before the West Indian went onto score what Sir Don Bradman called the greatest innings he’d ever seen played in Australia: a majestic 254 in the second innings.

Not that it stopped Lillee’s uncompromising bowling. Later that decade, this was how he summed up his approach to batsmen:

“I’m trying to scare him, trying to probably hurt him more than anything else. But I don’t want to cause any permanent damage or anything like that, it’s just a matter of trying to hurt him at the moment, perhaps in the ribs or the leg or something like that so that he at least knows you’re around and that he’s a bit wary about getting behind the next one.”

He also decided it was a good idea to kick Javed Miandad, and threw something of a tantrum when told he couldn’t use his infamous aluminium bat.

Off the field, though, it was a different story. After retiring, he was happy to pass on his incredible knowledge, becoming a vastly respected bowling coach – Mitchell Johnson was one of the many quicks who benefitted from Lillee’s tutelage.

He was also more than capable of leaving on-field battles in the middle, as Sobers attested to.

“He said to me, ‘I heard about you. I got my tail cut properly’. And I appreciated it… Dennis and I became very, very good friends after that.”

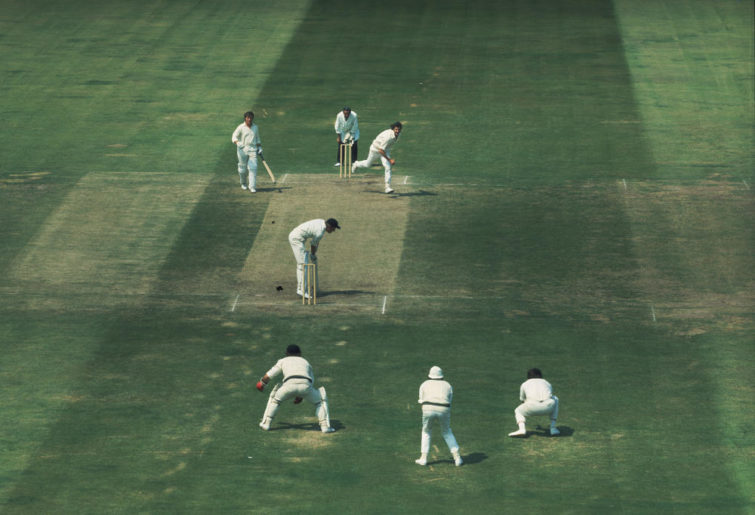

(Photo by © Hulton-Deutsch Collection/CORBIS/Corbis via Getty Images)

Steve Waugh

We need to get a batsman in here, and Steve Waugh certainly fits the bill on both fronts.

Since retirement, Waugh has been heavily involved in charitable work, both at home and overseas. The foundation which bears his name supports children and young adults with rare diseases, and he’s also been a patron of a children’s home in Kolkata, India.

Even around his aggressive, impressive Australian team, Waugh’s hard-nosed persona on the field didn’t extend beyond it, as Gideon Haigh wrote in 2000:

“Off the field, in fact, Waugh maintained an almost sunken profile. In person quite a shy and self-effacing man, he was instrumental in welcoming wives into the Australian team’s fold as a kind of civilising influence, receiving the phone call that offered him the Australian captaincy while watching Sesame Street with his daughter.”

Add in the fact he was named Australian of the Year in 2004, for his contributions to humanitarian causes and charity, as well as sport, and you have someone who scarcely resembles the hardened competitor that helmed one of the most dominant sides in cricket history.

Famous for championing mental disintegration, that hallmark of the great Australian side of the late 1990s and early 2000s, to call Waugh uncompromising would be selling him short.

Steve Waugh: Test cricket’s greatest winner. (AP Photo/Rick Rycroft)

While the approach led to astounding success – the 1999 World Cup, a world record of 16 Test wins in a row (of which Waugh led the side in 15), and a best-ever win rate of just under 72 per cent from 57 Tests as captain – it also provided some uncomfortable moments.

Take this example of Brett Lee targeting Proteas tailender Nantie Hayward in Australia’s 2001-02 series against South Africa, told in the former captain’s own words in his book, The Meaning of Luck.

“My instructions to Brett were simple: ‘Give him a couple of Short ones to see if he likes it.’ Not wanting to displease his captain, Brett’s first bouncer was perfectly executed, and it certainly gained Hayward’s attention.

“The second was just as fiery, and it had the No. 11 backpedalling away to square-leg to ensure his wellbeing. I now had two options as captain. Should I instruct Brett to bowl at the stumps and take an easy wicket, or should I inflict further mental interrogation on their bowling spearhead by requesting a bit more ‘chin music’?

“I knew the whole South African team would be watching, as they were getting ready to come out and field at the fall of the innings’ final wicket. To me, this was a golden opportunity to confirm our status as the dominant team in this series and issue a clear statement of intent, so I told Brett to direct the next bumper a couple of feet outside the batsman’s leg stump.

“The result was almost comical, as Hayward, fearing for his safety, retreated off the mown pitch and ended up metres away on the adjoining strip. The point had been made. Through the grille of his helmet, I saw a man totally rattled, unable or unwilling to take a few deep breaths and regain focus, so he could help his team get its first-innings total reasonably close to ours.”

That’s not to say Waugh’s approach was anything personal against the opponents it brushed aside. Only that, when winning held such paramount importance, things were going to get nasty every now and then. And they did.

The Bad Boys Mike Lowrey (Will Smith) and Marcus Burnett (Martin Lawrence) are back together for one last ride in the highly anticipated Bad Boys For Life, coming out in cinemas January 16. Book your tickets now!