It may be just an urban legend. Then again, there may be a grain of truth behind the Devil’s Triangle, the patch of water in the North Atlantic where several ships and planes have mysteriously disappeared, with no apparent explanation. In an age wedded to empirical proofs it remains an anachronism, a stubborn mystery.

The Devil’s Triangle for the Tier One coaches at the Rugby World Cup, will lie in their selections at number 10, 12 and 15. Get that wrong, and you can forget about your ambitions to lift the Webb Ellis trophy.

It is the patch of choppy, unforgiving rugby water where Eddie Jones finally disappeared out of sight with England only a few months ago. He has to rise from the land of the dead – or the merely the forgotten – and get those picks right for Australia to have a shot at winning ‘Bill’ in October.

Jones inherited a good combination back in 2016, in his first World Cup cycle with England. George Ford and Owen Farrell were already in the squad, fast friends since their school days together in Wigan and sharing an instinctive rapport both on and off the field. Add in first Mike Brown then Elliott Daly behind them, and Manu Tuilagi at centre, et voilà. That was a recipe that could, and maybe should, have won a World Cup four years ago.

Things fell apart for Eddie when he discarded Ford and installed Marcus Smith with Farrell in the twin play-making roles. It was a combination which never threatened to fire and Jones’ successor Steve Borthwick had seen enough of it after just one game in charge in the current Six Nations.

Eddie Jones may have returned to the other side of the world but the same issues still dog him like a foreboding mist of uncertainty, all the way back to the land of his rugby birth.

Can Quade Cooper return to full fitness in time for the World Cup? What is status of Samu Kerevi, now that he has refused a quartet of potential deals with the Australian Super Rugby franchises in order to stay in Japanese League One? Who is the likeliest lad to play full-back? All of these questions remain up in the air, skirting the Devil.

Australia’s closest rivals New Zealand have gotten their house in order by picking the trio of Richie Mo’unga, Jordie Barrett and his brother Beauden at the back. Their provinces are fully in synch and the Hurricanes will very likely select Jordie at number 12 in this season’s Super Rugby Pacific competition. As head coach Jason Holland commented recently.

“He [Jordie] is training for 12 at the moment for us mainly, so he’s probably a midfielder in our eyes at the moment unless other circumstances force him to play out the back,” Holland said.

“We pretty much do whatever we think is the best thing for the boys, and there’s nothing coming from ‘Fozzy’ to say ‘you have to play anybody anywhere.’

“They’ve obviously got their preference around where they see guys, and maybe we’re a bit closer together in our thinking now around Jordie.

“We can do what we want, but we’ll continue to have conversations with the All Blacks’ coaches.”

Ireland are settled with Johnny Sexton, Robbie Henshaw/Bundee Aki/Stuart McCloskey and Hugo Keenan. France can improve effortlessly when Jonathan Danty and Melvyn Jaminet rejoin one of either Romain Ntamack or Matthieu Jalibert. South Africa already has improved by moving towards the two Damians, Willemse and De Allende in midfield, with either Willie Le Roux or Cheslin Kolbe at fullback.

He may not have a Sexton to hand, but Eddie Jones urgently needs to find his sextant in order to navigate around the pitfalls of the Devil’s Triangle. The bare truth is that the twin playmaker system at numbers 10 and 12 is dead in the water at the top level – unless you happen to discover a pair with the uncanny understanding of a Ford and a Farrell.

All of Australia’s biggest rivals later in the year will primarily feature a lot of sheer size and power at number 12, but with more than just a frisson of triple threat. The very best of the best will feature a handful of back-line players who can all kick, run and pass effectively and take pressure off the main playmaker.

That is the current template, and it is why Australia needs all of Cooper, Kerevi and either Tom Wright or Reece Hodge in the same starting axis together, if they are not to fall further behind their main rivals.

England improved from Scotland to Italy in the Six Nations by the simple expedient of shifting Owen Farrell to 10 and bringing in a player with more physical presence (Bath’s Ollie Lawrence) alongside him. Steve Borthwick’s men looked more purposeful and better-structured than they had done in round one, with Lawrence’s gain-line wins in the first period tipping over into full-blown line-breaks in the second:

The triple threat handymen are all in evidence in that first clip, with centre Henry Slade passing to Lawrence on first phase, and Farrell still available to put the searching kick through on second. Lawrence makes a seismic, Kerevi-like impact on Tommaso Allan in the second example, running straight through the Italian outside-half from a lineout.

If Lawrence has shown the hand of 12-on-the-run with England, the man outside Finn Russell, under-rated Sione Tuipulotu, advertised what is possible on the pass and the kick north of the border. Tuipulotu was born in Victoria and played three seasons with the Melbourne Rebels between 2016-2019 before moving to Glasgow, and qualifying via residency for Scotland:

Many attacking teams currently like to forefront their number 12 on the first phase from set-piece, but Tuipulotu handles the role with a more lot nuance and genuine feel than most. In the first example he is looking back towards Russell before dishing the ball short to his centre partner Huw Jones versus Wales. In the second, he uses the running threat he presents to force the Welsh defence to stop and think before giving the ball to Finn and Blair Kinghorn in space.

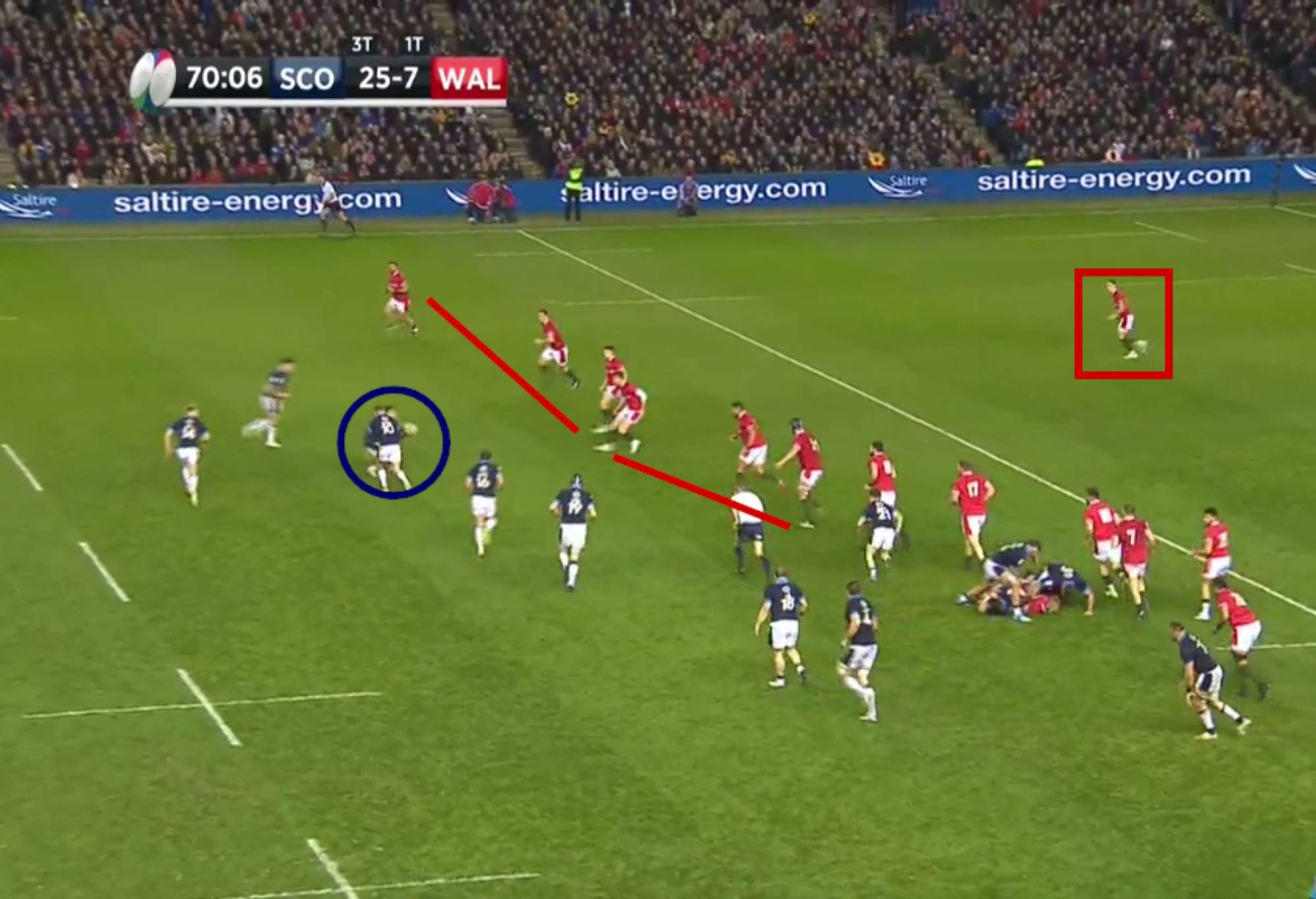

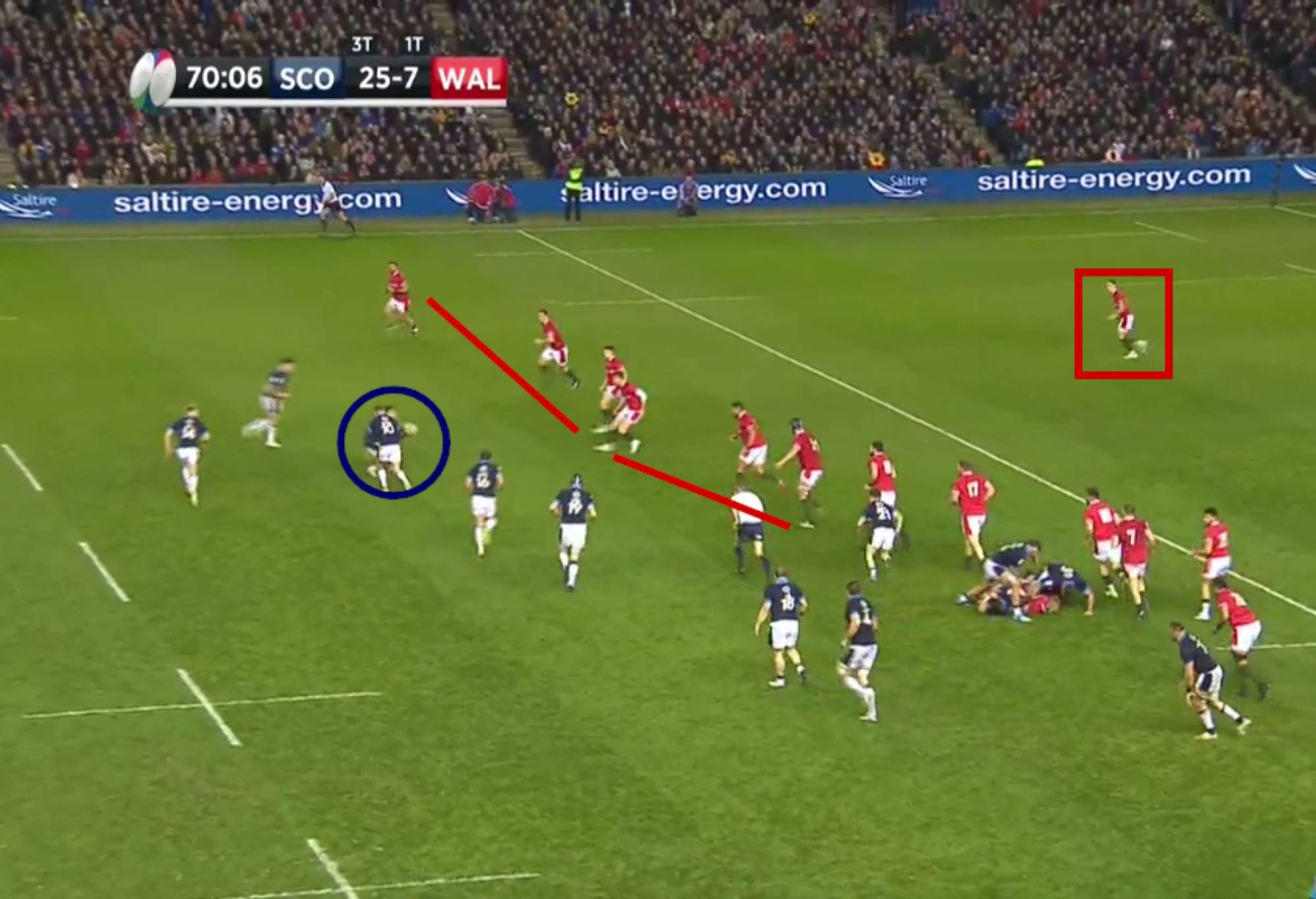

The point of this role reversal was revealed late on in the Welsh match:

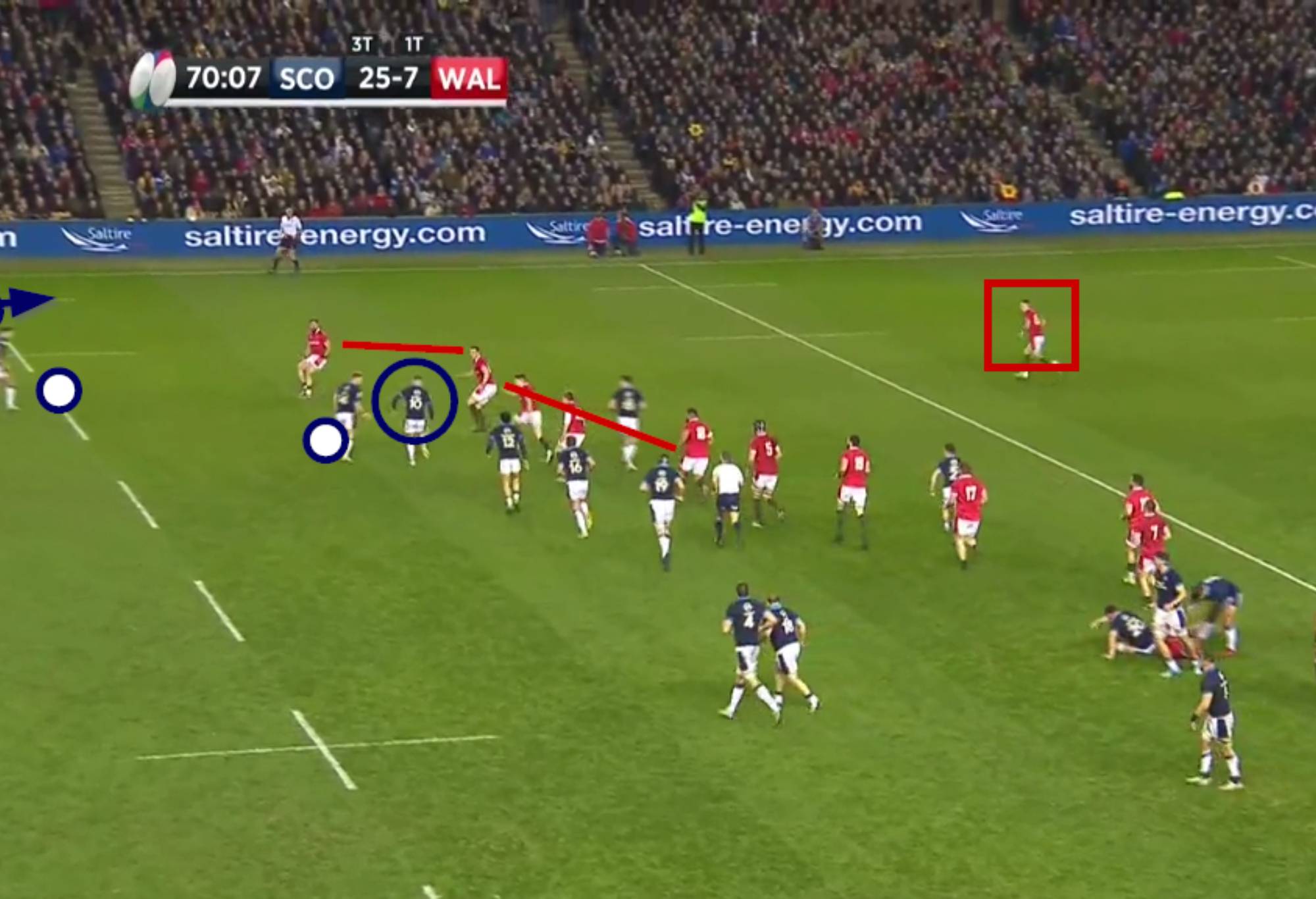

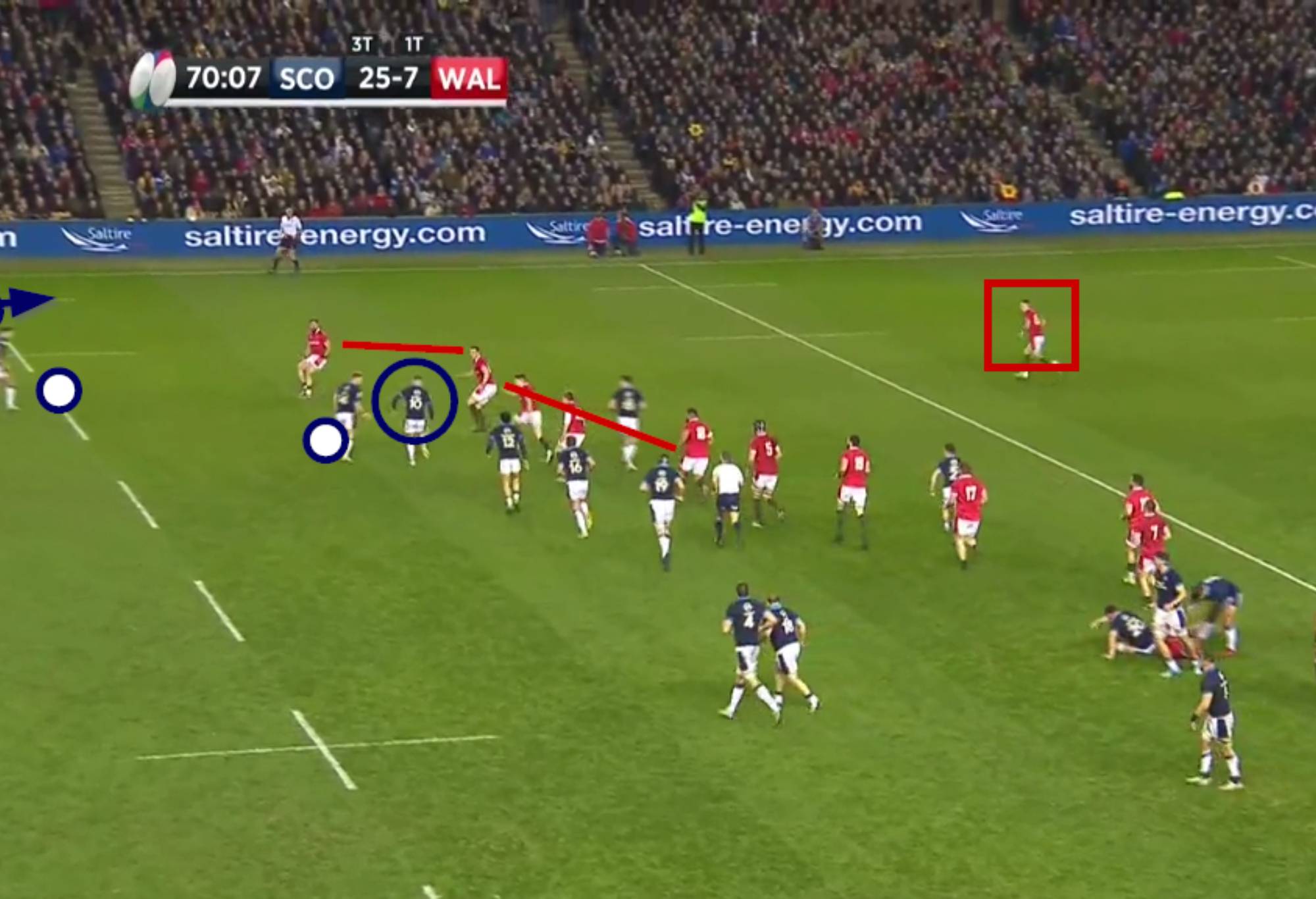

Sione stays square to the defensive line while pulling the ball back for Russell to deliver a deadly kick-pass to Duhan Van der Merwe on the Scotland left wing. Why kick off the second rather than the first pass? These two screenshots will help explain the subtlety:

If the kick comes off first receiver, the Welsh defence is still in a line, able to shoot up or double back and cover the space behind it. The second touch places Finn Russell closer to the target area on the left side-line and pulls the two Welsh defenders on the outside further up, making the turn-and-recovery that much more difficult.

Tuipulotu demonstrated his dexterity in the third prong of the triple threat during the first half against England:

With Russell running the shallow wrap behind him and an empty England backfield in front, the Australian-born Tongan puts a deft kick through for Huw Jones to touch down for the score.

Another Australian inside centre currently plying his trade in Europe had a big say in two of Clermont Auvergne’s tries against Leicester in a recent Heineken Champion’s Cup match:

That is ex-Brumby number 12 Irae Simone, twice popping up near the right touch to deliver killing offloads to his support. The first try should be marked “Made in the Southern Hemisphere”, with ex-Waratah Alex Newsome dropping the first pass on to Simone’s bootlaces and Argentine wing Batista Delguy up in support to receive the offload and dot down.

Summary

Given the way the game is currently being played at the top level, you do not need twin playmakers in the backline, and you certainly do not need them at numbers 10 and 12. You do need as many triple threats as you can muster, with the majority of backs able to run, pass and kick with almost equal facility.

That is why New Zealand have been able to move a man who was hitherto regarded exclusively as a fullback (Jordie Barrett) to second five-eighth with such obvious success. Jordie can run with power, but he can also pass, kick and act as a second fullback with his brother on defence.

Up north, Ireland with Johnny Sexton, Scotland with Finn Russell and lately England with Owen Farrell, all profit from their status as undisputed kings of the playmaking at number 10, with others able to contribute from numbers 12, 13 and 15 when the king is temporarily removed from the board.

What does it all mean for Eddie Jones’ Australia? The Wallabies have only one true king at number 10 in Quade Cooper, with a number of pawns behind him who might one day ‘Queen’ in their development. They have strength in depth at number 12, with the outstanding Samu Kerevi supported by the likes of Lalakai Foketi and Hunter Paisami.

They have Len Ikitau at number 13, possessing some of the left-side ball-handling and kicking qualities of a Henry Slade, and far more physicality than the Exeter man. With no time left to develop Jordie Petaia as a fullback in time for the World Cup, the choice should by rights lie between the two players who fit the modern profile best, Reece Hodge and Tom Wright.

Wright is the better runner and can connect his wings on the counter. Hodge can play a bit of 10, he has the physicality and directness of a centre, he can catch, tackle and owns the biggest boot in Australian rugby. You do not win 63 international caps in six different positions for nothing, even if the player himself continues to be cruelly under-rated in his own homeland.

To an outsider, the choice would be a simple one: Quade, Samu and Reece, with Tom on the bench. With the status of the first two murky due to a mix of injury and overseas unavailability and the third often disregarded, Eddie Jones is entering the Devil’s Triangle again. It was the same void into which his selections, and ultimately his job disappeared without a trace in England. Wallaby supporters can only hope that the hand they see above the waves is not drowning, but waving this time around.