Canis lupus: the gray wolf. When I dream of being a beast, I am a wolf running down prey.

They live and hunt with a pack but spend long periods alone. They howl to the pack: to let them know where they are; to control territory. But sometimes they howl for fun; just to be a wolf.

Here we are at the end of this mad series, having discovered history’s and Australia’s current rugby mastiffs, monks, bouncers, bank robbers, bears, jockeys, singers and fishermen. What about our last player, the man at the back, in acres of space, looking up at the sky more than any other, so often evolved from a position elsewhere, conspicuous in error, and feted as hero, too?

The fullback: known only as fullback in all nations (to be precise, “el fullback” in Argentina). Like the gray wolf, he moves about fifteen kilometres a day, and if you have ever been to a Test match live containing feral Willie le Roux or rabid Stuart Hogg, you know they can howl.

Tom Wright is considered the favourite to wear the No.15 jersey for the Wallabies. (Photo by Mark Nolan/Getty Images)

Lone wolf Tom Wright had a howler in the last match of the Brumbies’ season, tossing bones all over the show, and running into trouble at the end, throwing the identity of the least certain Wallaby position into even further doubt, but when Eddie Jones named his squad, there was the fierce lad on the sheet, with no obvious alpha dog threat, at least no healthy competitor.

The fullback must chart his own course more than any other player: the core skills and rush defence and line speed duties and rigorous attendance to task or the positioning of other players is so intensely confining that they scarcely see space through the match. Fullbacks roam.

But back to wolves. The largest wolf population in Europe is now in northern Spain, in the Pyrenees, where their roaming instincts do not often put them in contact with humans; in the foothills of the Pyrenees live the Basques.

This week in a hydrangea-draped Biarritz backyard at dusk as I picked bones out of my mouth, I was asked by Basque rugby player, a flank in a nine’s body: “How do you call zis?”

“Bones,” I muttered, using rosé to wash a stuck one down my gullet. The sea bream was dense and juicy; barbequed in salt and topped by herbs. No sauce spoiled it and clearly no fillet either.

He dissolved into laughter. “Fish have no bones!” The French word for a fishbone is “arete” (the end or edge). ‘Espinas,’ in Spanish, or thorns.

The Basques have backbone, but their history on the edge of Europe has had plenty of thorns. They occupy the salty forearm of Spain as it folds into the hairy bicep of Bayonne and Biarritz.

How do you get your own country? First, make sure it is at least 12 nautical miles from any existing countries. The Basques did not find that spot. Instead, like Wright wandering into a Chief turnover machine, the restless Basques stumbled from the Caucasus or Caspian across Europe until camped along wet peninsulas on the Bay of Biscay, known to the Romans as pesky seafarers (“Vascones”) doomed to fight a perpetual war of resistance against Visigoths, Franks, Normans and Moors; they even cut Charlemagne’s army to pieces at Roncesvalles (the Moors being the beneficiary of the enemy of my enemy ethos).

Only in 1937 were Basque lands finally subdued, except for the separatist claims of the hard-line “military” wing of the Euzkadi Ta Azkatasuna. In Spain, their comunidad autónoma preserves their unique language: it is the only European tongue not Indo-European. These lone linguistic wolves love to use x and z in their words: they must be Scrabble threats at the end of the game.

Also, the Basque tongue loves to compound nouns to form new words, as in bizkar-hezur or ‘backbone,’ which has allowed it to thrive when other conquered dialects died and is a good fit for their hybrid style of cooking.

On the Spanish side of Basque Country, San Sebastian seems to have a top chef for every 20 inhabitants. In truth, this small city of blessed bays founded by shipbuilders has 16 Michelin stars (a ratio of 12,000 people per star compared to 112,000 people per star in London). Basques do pintxos, not tapas; it must have an x.

Packs of bearded Basques with packs of cigarettes wedged in their back pockets go from pintxos bar to pintxos bar, wolfing down octopi and squid resting precariously on toast, adorned with unidentified eggs. This social tradition of going from one place to another in a growing group is called txikiteo.

In my rugby teams we always called that a pub crawl or a booze gauntlet, but the food was shit.

Who is the most famous Basque sportsman?

Goalkeeper Iker Casillas kept goal for Spain 167 times and holds the record for most clean sheets in several competitions; excellent at the core skill of goalkeepers and rugby fullbacks of howling at their mates. If acting is sport, Basque Javier Bardem would be up there. Creative golfer Jose Maria Olazabal could win even driving into the jungle because his hands were so good. Rugged Imanol Harinordoquy, Basque-speaking native of Bayonne, was one of the best number eights.

But we will anoint Serge Blanco, French fullback and the Pele of Rugby, as the best Basque back of all time; he was born in Caracas to a Basque mother and raised in Biarritz. His 93 caps were won in an era before Test centurions had happened and scored 233 points with his inventive brand of counterattack: flamboyant and devastating in space, as Wallaby great David Campese can confirm.

Serge Blanco is one of rugby’s greatest fullbacks. (Photo by Russell Cheyne/Getty Images)

Encapsulating what a fullback must and should do is difficult. There is a theory that a 15 is the alter ego of the coach, because he is a coach on the pitch, and has the most time to enact and calibrate the pretty plans. Thus, we can see Rassie’s naughty nature in Spiders le Roux or Gazza Willemse; the wild side of Gregor Townsend in Hogg; Warren Gatland’s prickly nature in Liam Williams; Fabian Galthie’s deadly calculus in Thomas Ramos; and Andy Farrell’s focused equilibrium in Hugo Keenan.

Look at run metre statistics: fullbacks lead most competitions because they have a free 10 yards on the catch. The metres made chart for the Six Nations featured Keenan 562 metres and 11 broken tackles, Ramos’ 502 metres (13 broken tackles), and Steward’s 453 metres (12 broken tackles). A hundred of those metres for each is likely in open space; contrast Antoine Dupont busting 17 tackles in just 256 metres of carry.

But making the wrong choice on kick long, kick up, kick on the angle, pass the buck to a mate, or go on an expedition to be snaffled or not. No other player has this freedom and fate.

In this year’s Six Nations, Steward conceded four penalties, Ramos five, and Hogg lost five turnovers. If you want to know why Ireland won, these three figures will take you a long way.

When kick tennis ensues, fullbacks also pad their kicking metres because they get the full windup and can even employ an old school spiral, like Hogg is fond of, until it fails, inevitably when Scotland can least afford it. Ramos kicked an almost unbelievable 1,354 metres in the 2023 Six Nations, or 270 metres per Test. The French system depends on the Ramos backbone.

The understated Hugo Keenan has emerged as one of the best fullbacks in the world. (Photo by David Rogers/Getty Images)

When pundits speak of a spine in rugby, they include the fullback. The story goes: give me a great hooker, excellent numbers 8-9-10, and a 15 of the highest quality, and I can win with 10 decent players everywhere else. We can quibble about the absence of a strong four, but the point is everyone puts 15 in the spine. The vital factor of a strong fullback remains: the wolf at the backdoor. The distance on his kicks. Knowing where our territory begins and ends.

Being able and willing to go all 80 and never switch off every time. Fullbacks are favourites of fans. JPR Williams herky-jerky motion, Christian Cullen’s blistering pace, Andy Irvine’s smooth speed, Don Clarke’s unerring boot, Scottish hero Gavin Hastings, the ebullient Israel Dagg, lightning Jason Robinson, and dogged Leigh Halfpenny are all easy to conjure in the mind’s eye. Tom Kiernan of Ireland, Gareth Thomas of Wales, and George Nepia of New Zealand also merit mention. Fullbacks are less cookie cutter in today’s rugby than any other slot. Elegantly languid Freddie Steward keeps leaving it late to take the ball, but beat the man, and then settle down for the ruck. He seems unhurried, but perhaps too insouciant to spark English dreams of glory. Similarly lanky Jordie Barrett hits kicks so high it seems they will never come down, but he keeps toying around with playing inside centre as when he took a burger into the wrong Dunedin flat to eat. His failure to spot an outside man in space in the Hurricane exit from the finals: food for thought.

Is busy Damian McKenzie even now, even after the beauty of his flyhalf 2023, a 15? He can be jammed when first receiver, but in space, he does have a way of separating himself.

Hogg is the gnashing, emoting symbol of Scotland’s “greatest generation” who seems to have lost just as many matches as he won with moments of madness. Of all the top fullbacks, he resembles Wright the most, except he is faster and kicks further.

Scotland’s Stuart Hogg (L) has a maverick element to his playing style at fullback. (Photo by Paul Devlin/SNS Group via Getty Images)

Irish hero Hugo Keenan might be the tidiest 15 of all: try to find a moment in any recent game where Keenan is out of position. Whether he can run as fast as some or leap as high: not as important as his understanding of where he should be. Jock Campbell of the Reds fits into the Keenan mold, but obviously without the white fang belligerence Eddie Jones likes.

Speaking of junkyard toughness, Liam Williams supplanted the more traditional kick-first Leigh Halfpenny at the back for Wales, and as long as he is on the pitch, his team has a puncher’s chance. I have never witnessed, live, a more talkative, cocky player (who backs it up, I will add).

When we had Eddie Jones on our podcast, he mentioned French backstop Ramos specifically: the sickening sound on his clearance kicks is the soundtrack that keeps Romain Ntamack safe. He also kicks for poles, which is a skill many fullbacks have carried for their teams.

For the Springboks, who often mandate 9-10 play more strictly, and need a spark from the back, Damian Willemse has replaced le Roux as the first-choice Bok magician, which brings up another issue: how many fullbacks can easily slot into other positions at will.

And then there’s Australia. The unknown.

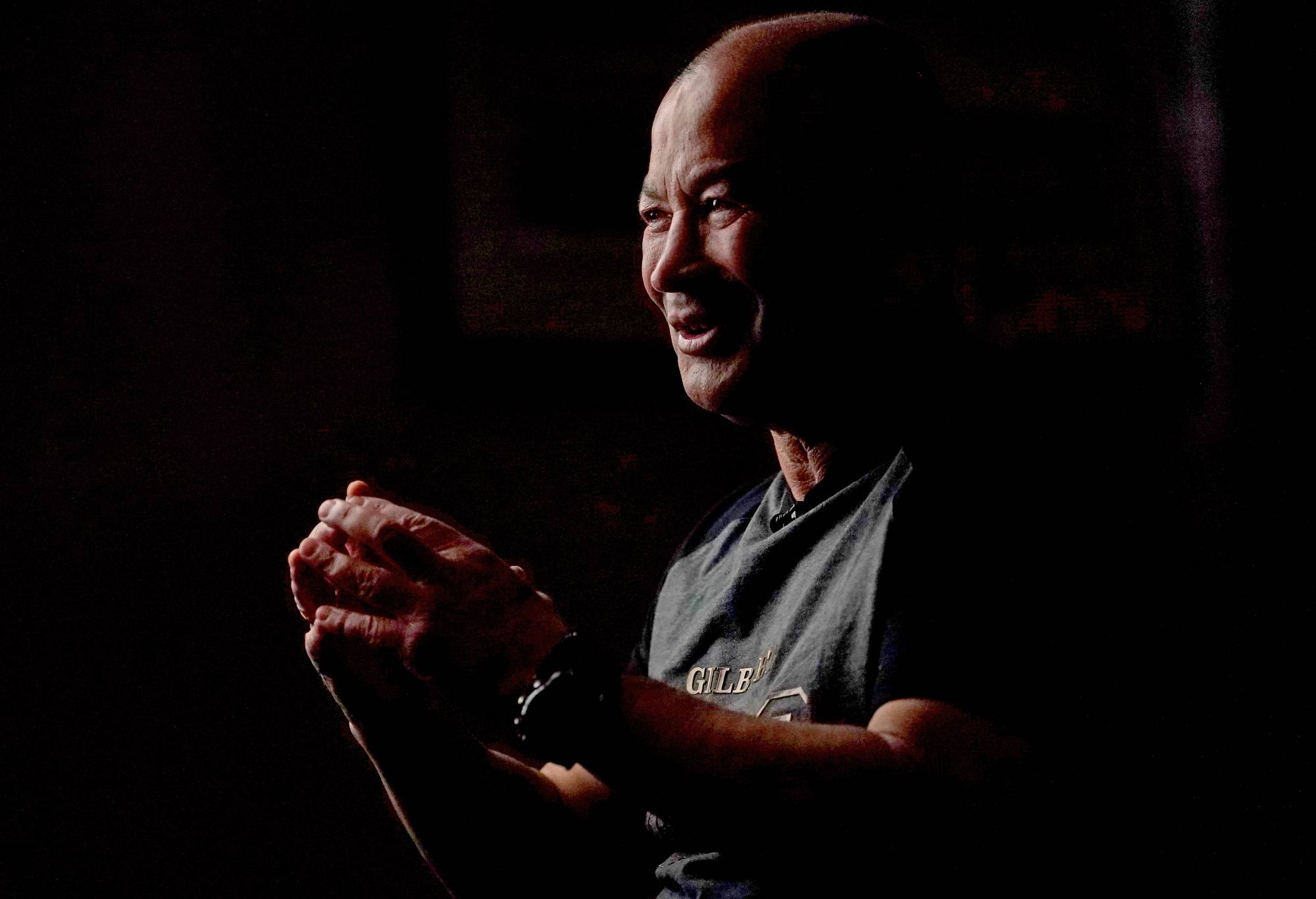

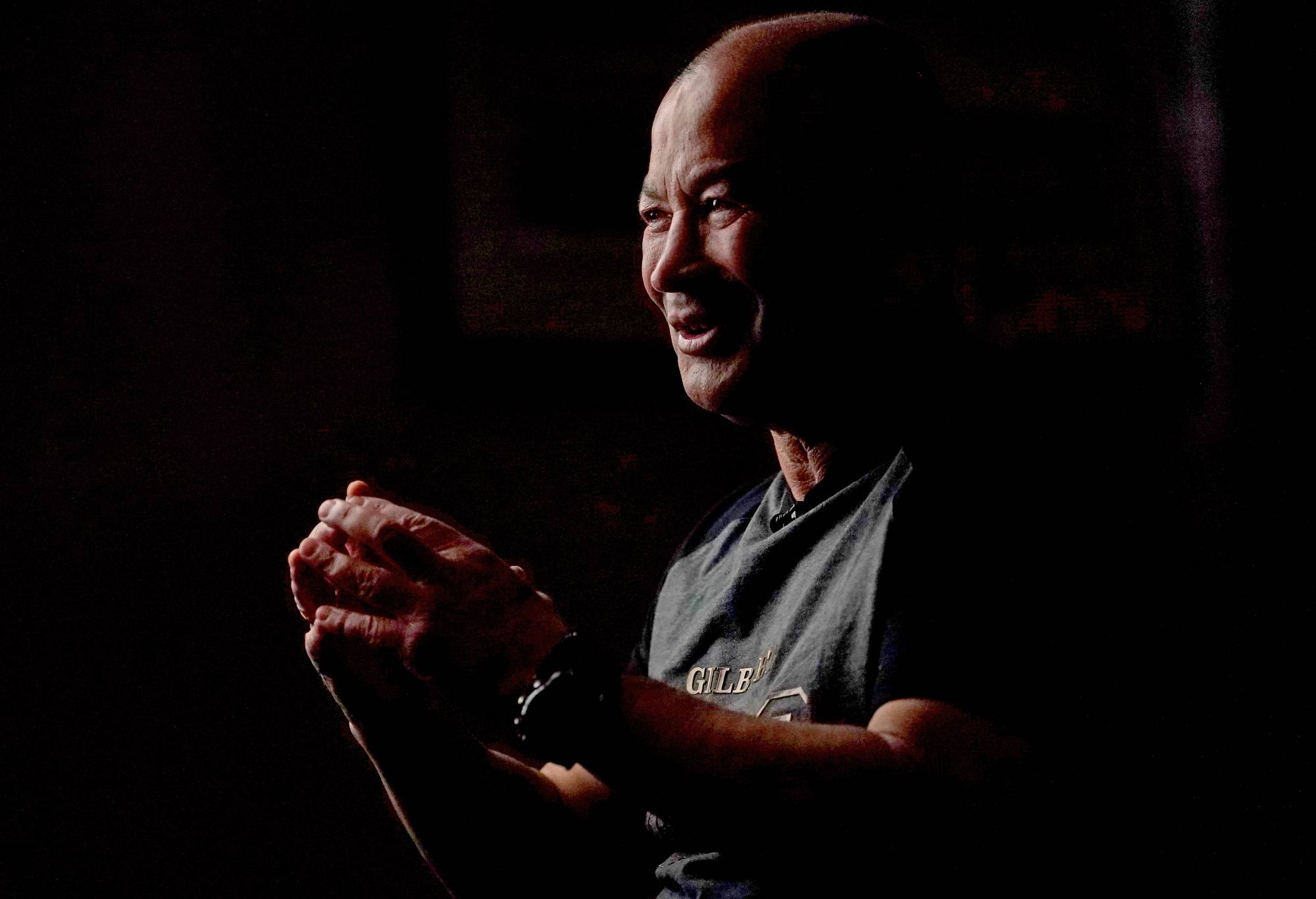

Barbarians coach Eddie Jones during a press conference at the Royal Garden Hotel, London. Picture date: Wednesday May 24, 2023. (Photo by Adam Davy/PA Images via Getty Images)

Earlier this year, Jones said Wright “has the ability to be the world’s best fullback.” He added: “That’s the challenge for him, how much more can he find?” If Joseph Suaalii was taken aback by Jones’ faith in Wright, one should point out Wright was a schoolboy prodigy in both codes, too, making five appearances for the Manly Warringah Sea Eagles in 2018.

Australian fullbacks have often been code jumpers. League convert Mat Rogers, a 45-cap Wallaby who scored 14 tries and kicked 46 goals after Waratahs coach Bob Dwyer (“Honestly, he could wear jumpers 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, or 15”) shifted legend Matt Burke in 2002 to accommodate the switch. In 2003, Rogers was number 15 in the World Cup final; with one missed pass to his mate Lote Tuqiri, a poor chip into touch on attack, a massive Garryowen, strong 40 metre clearances, a mark, and finally, quiet competence on a day when a spark was needed.

Is Wright the new Rogers? Wright divides public opinion in a way Jones may recognise. His good moments are big. His errors are large, as well. A couple of mistakes by a fullback, a charge-down or kick out on the full or missing a read or tackle or getting jackaled on an ill-advised runback: cost a team five points more easily than any other position’s mishaps.

The plus side of 2023 for Wright was confidence. He ran 178 times for a Super Rugby Pacific leading 1,855 metres and 13 precious line breaks. The minus came in the finals, when up against Shaun Stevenson – the Kiwi Wright – he was outshone and badly. He was turned over at a crucial moment, unforced, and did not inspire his teammates with confidence by trying first round antics in a grim semi-final.

Mat Rogers played fullback for the Wallabies in the 2003 Rugby World Cup final. (Photo by Nick Laham/Getty Images)

Stevenson did not make the All Black squad; but Wright seems to have the inside track. As Jones notes, he has the physical attributes to be an alpha, but why did he not track down and cut down forwards running free, twice? Why is he often in the wrong spot at the wrong time?

This is when instinct matters. A wolf’s territorialism and maneuvering big animals into kill spaces passed to canines in the form of a livestock herding instinct, which can operate almost uncannily to see space before it exists. But also, a wolf gave a dog devotion to the cause.

A great fullback can be relied on to see it all before it happens. This is when conversion hurts. It is difficult to play fullback in a World Cup knockout match. You are all alone and every kick is your concern. You are all alone.

One of Australia’s finest fullbacks, Israel Folau (73 caps and 37 tries) never truly mastered the kicking game.

Even fullbacks who always played Union were often positional converts: le Roux went ten-wing-fullback and played fly-half in Japan this season under Steve Hansen. The Barrett brothers both started elsewhere in schools before being in an unlikely duel with Will Jordan for the new, controversial All Black fullback jersey. But we can say now that all four of these men are Test level fullbacks.

Utility man Reece Hodge would bring a second goalkicker with him into the 15 jersey. Ben Donaldson is named in the squad and feels like a fullback more than a fly-half at Test level; but maybe neither.

So, when we think of mastermind Jones, do we see Wright’s wrongs, Hodge’s utility, or Donaldson’s brooding brows?

In the “wings” wait Andrew Kellaway, Jordan Petaia, and Mark Nawaqanitawase, who can play at the back, and all bring merits, particularly Petaia, in a ‘smash and grab’ job.

Or it more of a process of elimination: the most traditional of 15s — Jock Campbell — was too vanilla? The fullback should work with the two wingers to make up a back three that can cover all of the pitch and not allow any opportunities. Are Campbell or Kellaway better at that than Wright? Are they more scalpel than sledgehammer; more Michelin than burger?

Could Jock Campbell make a late charge to wear the No.15 jersey for the Wallabies? (Photo by Xavier Laine/Getty Images)

But we are not discussing who should be fullback from 2024 to 2027. The only focus is on beating Wales and Fiji, England or Argentina, and two of the top four teams in the world. Jones has made a rod for his own back by saying a trophy is all that matters; given the favourable draw.

Which Wallaby is capable of that, as a fullback? Who has won World Cups as 15s? What can we extrapolate from that list?

Working backwards, in 2019, much-maligned le Roux conclusively out-dueled Elliot Daly on the day, after outpointing Welsh and Japanese stars. If Jones thinks a lot of that day, and he says he does, he will not pick a Daly type, who struggled with high balls. In 2015 in London, tidy Ben Smith shaded big Folau. In 2011, Dagg just about outdid Maxime Medard. In France in 2007, using a Jones attack plan, it was the well-coiffed Percy Montgomery denying League convert Robinson. In 2003, Josh Lewsey took care of Rogers. In 1999, impeccable Burke bested Xavier Garbajosa, who was just axed by Lyon as a coach after only one season of strife. In 1995, the ‘Rolls Royce of Fullbacks’ Andre Joubert was a wee bit better than the Maori constable, Glen Osborne. In 1991, the good doctor, Marty Roebuck took on losing fullback Jonathan Webb. In the first edition, the great Irish immigrant All Black John Gallagher (41 caps and 252 points) broke Blanco’s big Basque heart.

What can make of all that? There were more exciting fullbacks than the nine winners, but the tenth is likely to fit neatly into that group of 10 later this year. One would bet on Ramos over Hogg, no matter how much more exciting the Scot is; similarly, Keenan appeals over McKenzie.

The Wallaby 15 should be more Burkean than Israelite, a wolf connected to his pack and his ancient roots, and ready to fight like a Basque for territory, but win the Cup by not losing.