'An iconic roster': LeBron, Steph, KD headline all-star cast for Team USA's shot at Olympic glory

LeBron James is going back to the Olympics for the first time in 12 years. Steph Curry is headed to the games for the…

For the best part of 50 years Australia punched above its weight on the world stage in sport. That all changed at Montreal in 1976.

The country’s sporting failure led to significant changes.

Australia was left behind, failing to realise that sport had shifted from the amateur endeavour where Dawn Fraser, Murray Rose and Shirley Strickland succeeded to the fully professional world that culminated in the first ‘McDonald’s’ Olympics of 1984.

America saw where the world was headed and reacted in 1972 after ‘just’ 33 gold medals at the Munich Olympics where the Soviet Union embarrassed the world power with 50. The United States’ 33 gold was 12 short of the 45 it won at the 1968 Olympics.

As a result of Munich, the United States Sports Academy was set up by Dr. Thomas P. Rosandich with a focus on proper coaching, medical support to reduce injuries and delving into sports science.

Australia’s eight gold medals at 1972 was considered a success. It was an increase from five in 1968. However, three of those gold medals came from teenage sensation Shane Gould and six out of the eight were all from the swimming pool.

It masked the fact that Australia was not succeeding in other sports and had too many eggs in one basket.

By the time 1976 came around, other countries had fully embraced sports science and the importance of funding sport.

As we know a large part of East Germany and the Soviet Union’s success was through cheating by doping athletes, but it shouldn’t be overlooked that they had the right systems to have athletes with any sort of ability in the first place.

This came from the basics of teaching all Olympic sports at schools to subsidising sports clubs.

In contrast, minimal funding was given to sport in Australia. There had however been national fitness initiatives as early as the 1940s. Sports academic John Bloomfield had urged and recommended the ‘development of programs in areas such as sports management, coaching, talent identification and sports science and medicine’ in 1973.

Like a scene out of the ABC show Utopia, feasibility studies were commissioned and the idea of a national sporting institute was endorsed – but that was about the extent of it.

The Whitlam government started to give out government grants but its time in office had come to an end. The total government funding for the 1976 Australian Olympic team was just $250,000.

It took the disaster of 1976 for the country to realise how desperately a sporting overhaul was needed.

Why was it so bad?

For a start, Australia didn’t pick up a single gold medal for the first time since 1936. Even New Zealand claimed two. Australia finished 32nd on the medal table, just ahead of Iran and Mongolia.

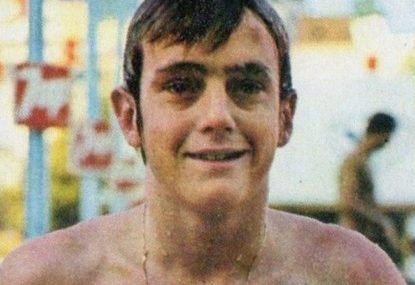

The sum total of the 180 athletes was one silver medal to the men’s hockey team and four bronze medals: in team equestrian, two in sailing and just one in the pool with Steve Holland coming third in the 1500-metres freestyle.

In short, it was an embarrassment to a sporting nation, even if that sporting nation was small by population. There were protests in the streets and the Malcolm Fraser-led liberal government was forced to re-evaluate its decision to cut sports funding when it came to power in 1975.

It didn’t help that Australia’s failures were magnified with live television coverage of the Olympics for the first time.

Steve Holland lamented that he didn’t have a proper gymnasium to use, and was training in a sub-standard 25-metre pool. He saw the strength of the USA swimmers as they powered to the gold and silver medals at the end of 1500 metres.

Holland’s time was at world record pace but that was forgotten in the wash-up.

“No one gave us any money or anything,” Holland said in a Timeframe TV interview.

“There was nothing. What we did was for Mum and Dad, slaving their guts out working to try and keep me at world standard.”

“I still broke the world record. Still got the bronze, but it was considered a failure.”

Sprinter Raelene Boyle was disqualified in the semi-final of the 200 metres for false starts, which ended the disaster of Montreal.

“We were working jobs and being athletes, whereas the rest of the world were just being athletes,” Boyle said.

After Montreal, assistance and cash was funneled to the Australian Olympic Federation while the Brisbane Commonwealth Games to be staged in 1982 became a priority for funding.

The famous ‘Life Be In It’ campaign went nationwide to encourage all Australians to be active.

Finally, in 1981 the Australian Institute of Sport (AIS) was established. Its goal was to nurture Australian talent and inspire ordinary people to emulate elite athletes.

Despite being based in Canberra, 800 athletes applied for the initial intake.

For those who claim sports funding doesn’t make a difference, one only has to look at Australia’s rise in the winter Olympics. After Australia’s winter Olympic program was fully funded for the first time, Australia went from having zero gold medals in its history to five with at least one gold in three consecutive games (2002, 2006, 2010).

According to a 2012 Crikey article, the price of each summer Olympic gold medal now equates to roughly $50 million.

The funding model has since changed from how the AIS was originally set up with individual sports now in charge of their own destinies. It’s led to accusations that too much money is being spent on elite athletes and not enough on finding and supporting emerging talent through scholarships.

Those who are critical might point to Australia’s failure in the pool in 2012 with just one gold at London (how much of that was due to a discipline problem is another story).

However, Australia scored seven gold medals elsewhere. Seven gold medals against athletes that all see sport as a job and a business.

Steve Holland felt like the 1976 team were the sacrificial lambs to prove once and for all that amateurism wasn’t sustainable for the expectations Australians had of its Olympians.

Whatever happens at Rio, Australia’s athletes will know they were given the best possible chance to succeed thanks to the investment in their sport from a sport-loving nation.