Imagine we have an object about the size of a dining table weighing 200 kg and it needs to be moved. There are 11 men of average strength in the nearby vicinity.

Do we need all 11 to lift the object? If not, how many will be needed? What if there are only five such men nearby, will they all be needed? What if there were only two men, but were both capable of summoning extra strength neither had previously believed they possessed?

A team’s batting innings is a bit like that. Sometimes all 11 batsmen are needed to reach a certain total, sometimes a mere two or three of them is sufficient, depending on the intensity level of the situation. The times when only a small number of batsmen are required to get the job done are much lower intensity than the high-pressure occasions when all 11 are needed.

Rarely will everyone in a line-up fire in the same innings, and this fact of cricketing life requires someone somewhere among the batsmen to have their day and respond successfully to the high pressure of their batting colleagues failing on any given day during the critical phases of a match.

In Melbourne against the West Indies on 26 December 1981, Greg Chappell, Allan Border, Graeme Wood and Bruce Laird all failed, requiring Kim Hughes to stand up. Had he not done so, then it is an almost certainty that the lower order would not have found the grit to hang around and support him to turn a 60 or 70 total into 198.

Those 100 unconquered runs of Hughes’ that day were as priceless as any 100 runs ever scored in the history of Test cricket, far more priceless, for example, than any of the 775 scored by Lara across a mere two innings, ten years apart on the same ground, the Recreation in Antigua.

Those 100 runs by Hughes were more valuable than any of the 204 runs Bradman scored beyond lunch on that first day at Headingly in 1930.

There are many examples of runs made by one particular batsman being more valuable than an equal or even greater number made by another somewhere else on a different day. In a Test where all 40 wickets fall and one team wins by a small run margin, then every single run scored in that Test has value.

The same applies to a Test where 38 or 39 wickets fall and one of the team prevails by a mere wicket or two. However, in a Test where one team wins by either runs or wickets, and loses only 12 or 13 of their 20 wickets in the process, then certain runs made by their batsmen begin to diminish in value, simply because they didn’t require all of their line-up to contribute, so therefore, the pressure or intensity gradually evaporated.

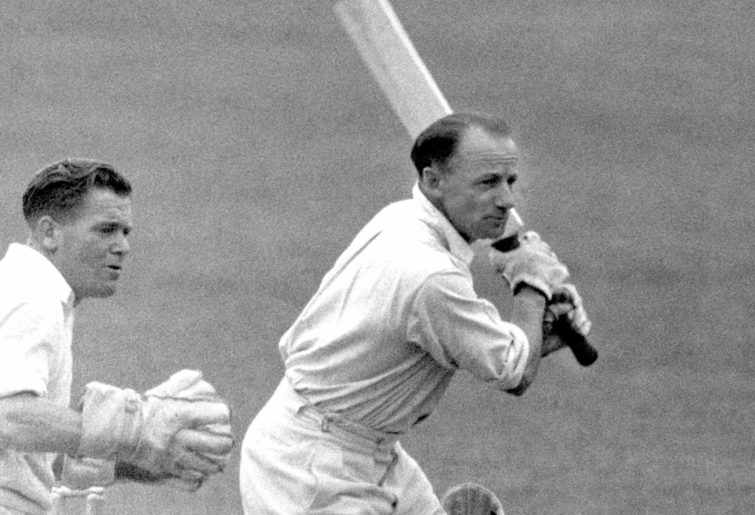

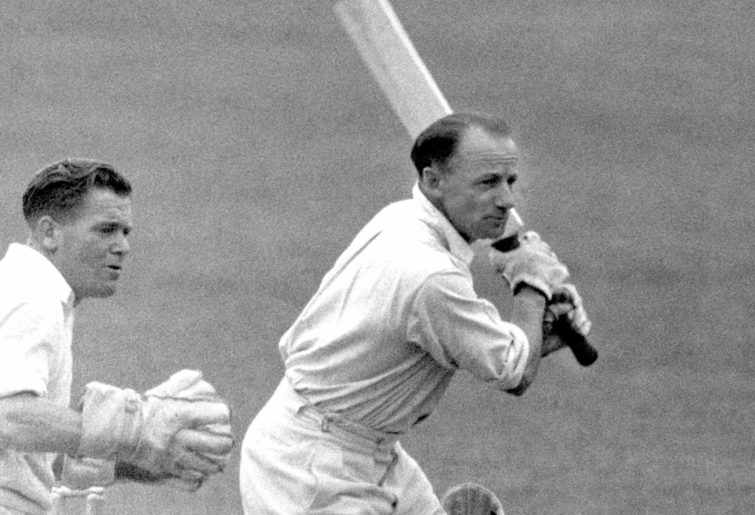

How much are runs worth? (PA Images via Getty Images)

This brings us to the concept of runs of lesser value or even, on occasions, totally meaningless runs. The terminology ‘meaningless runs’ does not mean that runs didn’t need to be scored by the team as a whole, but rather, the pressure valve was released to very low or zero intensity so that such runs being scored became a certainty.

Australia reaching 599 in Peschawar in late 1998 only required six of their 11 players to achieve it. Therefore, reaching 599 was so certain that it only really needed any of their main batsmen, on average, to contribute about 80 each, so any runs scored beyond that rough figure by any individual batsman are of gradual and greatly diminished value.

In pursuit, in order to get within 19 runs of Australia’s mammoth total, Pakistan required 10 of their 11 batsmen, so therefore, all of their runs scored have equal value. Ijaz Ahmed’s 155, Saeed Anwar’s 126 and Inzamam-ul-Haq’s 97 were all worth that precise value, whereas Langer’s 116 and Taylor’s 334 had limited real value too far beyond that aforementioned 80.

An upward adjustment can naturally be made for the fact that Slater, Mark Waugh and Steve Waugh made only 45 between them, with Ponting undefeated on 76 at the declaration and 28 extras.

So, if we assume that Healy and the bowlers would probably have been good for at least about 100 runs, then Langer’s 116 are all valuable, while Taylor’s (334) ceased to be of any real value too much beyond about 200.

There are a multitude of situations where additional runs scored by a particular batsman begin to reduce in value and even on occasions cease to have any real meaning whatsoever in terms of a genuine direct contribution by that batsman to the team’s success or failure. Here are a few.

Lost causes in fourth innings run chases

A good example is the deciding Test of the 2009 Ashes at the Oval. Australia were so far behind in the game, due entirely to simply not scoring enough in their first innings, that a victory target of 546 was simply unachievable.

To make matters worse, a draw was also, for all intents and purposes, out of the equation because two whole days remained.

If a team bats for two days in the 21st Century, then they are going to make close to 550, and yet no team is ever likely to successfully chase down anywhere near that many in the fourth innings. So, with defeat a forgone conclusion, nothing any batsman subsequently did, could have any possible meaning in terms of influencing the result.

Mike Hussey’s 119 and Rick Ponting’s 66, for example, were 185 runs as meaningless as any batsmen could ever score. There have been many such examples through the history of Test cricket, and there will be many more in the coming future.

Ricky Ponting in 2006. (James Knowler/Getty Images)

Chasing down a small target in fourth innings

When Joe Burns hooked a six to reach 50 and simultaneously finish off the first Test victory against India in Adelaide last summer, we all rejoiced and felt sure he had turned the corner and was set for a productive summer.

However, they were 50 runs as meaningless as any runs could be because it would be pretty hard for an entire line-up to mess up a run chase of only 90.

Had Burns been out for a duck, then the other five batsmen in the line-up would only have needed to contribute 10-15 runs each to get Australia home. There have been many such 10, 9 or 8 wicket victories in targets up to about 200 and there will be many more to come.

In the second Test in Melbourne, with the pressure back on due to openers needing to make their mark on the first morning of the match, Burns once again failed, unfortunately.

Setting a massive target with a third innings declaration

A great many centuries scored in the third innings of a match are made in declared totals of 1 to 3 wickets down for anything upwards of 200. A perfect example is Justin Langer’s unbeaten even 100 in the third innings of the first Test of the 2006-07 Ashes in Brisbane.

Australia made 1 for 201 before sending England back in and the 160 Langer and Ricky Ponting made between them also falls into the category of runs as meaningless as any individual batsmen will ever score.

If the match situation dictated that Australia were only going to need to score 200 in their second innings, then it made absolutely no difference whether they got to that 200 nine down or with their openers still together. In the circumstances of that actual match, reaching 200 in their second innings was a certainty for Australia, so there was zero pressure on any batsman to score 100 or 60 or anything in between.

As long as each of the seven batsmen counting Gilchrist averaged about 25 each, then they were always going to be able to set England what they wished to set them.

In that particular match, Ponting’s 196 was of course the backbone of the massive first innings total of nine declared for 602, but Langer’s own 82 was also of much greater value to the team’s fortunes than his token century in the second innings.

In fact, Hayden’s 37 on the first morning of the series was of much greater value to Australia’s fortunes in that series than Langer and Ponting’s collective 160 second innings runs.

Drawing after wiping off a first innings deficit or expanding on a minimal lead

Three instances spring instantly to mind: the third Test in Durban between Australia and South Africa in early 1994, the third Test at Edgbaston of the 2009 Ashes, and the fifth Test of the 2005 Ashes at the Oval.

All three instances involved the side batting in the third innings needing to get far enough into a lead in order that their opponent would not have enough time left in the match to chase down any target set should the side batting third end up getting bowled out.

Only in the 2005 example did the side batting third actually get bowled out. All three instances involved runs having priceless value up to a certain point beyond which they were subsequently safe from defeat.

Given that all were identical situations, it is only necessary to dissect one of them and I will choose the Oval 2005 one. Australia’s last chance to win the match was undoubtedly when England lost their seventh wicket 205 ahead with 52 overs left in the match, allowing for a change of innings deduction of three overs. They needed to get those three wickets super quickly without England extending that lead too much further.

Ashely Giles hung around for a partnership of 109 with Kevin Pietersen to make the match safe. However, the match was well and truly safe for some time before Pietersen was finally dismissed, 8th out with the lead stretched to 314. When England were finally bowled out, Australia needed an impossible 342 off 18 overs.

When only 40 overs of playing time remained, England were already 250 ahead, with Australia still needing three wickets, so by this point England were safe from defeat. From that point, probably about the final 30-35 of Kev Pietersen’s astonishing 158 runs fell into the category of diminishing value to outright meaningless.

Kevin Pietersen (Photo by Tom Shaw/Getty Images)

Lost causes in insurmountable deficits on first innings

There is no better example than the recently concluded Test between England and India. When you trail by 345 runs at the end of only the second day, then you have no hope of even drawing the match.

In the extremely unlikely event that you will then score 500 in your second innings, that only leaves your opponent still less than 150 to chase, with plenty of time to do it – any grandiose ideas of victory will only have you in the territory of needing a miracle along the lines of either Headingly or Edgbaston in 1981.

Joe Root was on about 40 or 45 when England reached 250 in their first innings, already 172 ahead. Only six times has a team won a Test after trailing by 200 or more, and I would imagine not a hell of lot more occasions with a deficit in the 170 – 200 range.

Although some of Root’s recent Test hundreds have come in situations of genuine pressure, this was not one of them. Going in with the lead already nearly 100, the first 40 – 45 of his 121 runs were in the low intensity region, the last 75 – 80 about as meaningless as runs come.

Even if Root had done a Victor Trumper and just teed off from the moment he went in and made a quickfire 30, the remaining eight batsmen counting the tail would have had less than 100 to make between them to get the total to 300, which is still a lead of 222. Then India’s 2nd dig of 278 would have left them needing a mere 57 to win.

I know people’s hopes start to rise in such situations where a team reaches 2 for 215 as India did. However, such rising hopes usually turn out to be like a mirage to a thirsty traveller in the desert, because in such situations, sooner or later, the scoreboard pressure begins to tell and a collapse is never that far away.

It is not especially common in such situations for teams to mount one long, large partnership after another to even stave off defeat, let alone miraculously turn the match on its head.

It goes without saying, that all runs scored in India’s second innings were always going to be completely meaningless to influencing the match result.

(Photo by Stu Forster/Getty Images)

Large totals after bowling a side out dirt cheap in first innings of match

As all matches dissected thus far have been post 2000, I thought I would find an example further back in the distant past. At the Oval in 1948 Australia bowled England out before lunch on the first day for 52 and then made 389 in reply, Arthur Morris making 196, opening the innings and being eighth out with the score on 359.

Bradman’s famous duck was made in as pressure less a situation as there could be in a Test match, going in at the fall of the first wicket with his team already leading by 65.

Additionally, we can estimate that roughly the last 70 – 75 of Morris’s runs held absolutely no value to influencing the actual result of the match, and the team innings would have already reached little or no intensity once the total was not too far past 200.

Mammoth first innings totals declared with a fair amount of wickets still standing

In late 2003-04, even without McGrath, Australia did not need to score 735 to defeat Zimbabwe, even by an innings.

Zimbabwe probably batted out of their skins to even total 560 for their two innings, so let’s cap Australia’s total at that. Against Zimbabwe’s attack, a tail of Andy Bichel, Brett Lee, Jason Gillespie and Stuart MacGill plus extras could easily have contributed 100 runs.

The other six batsmen apart from Hayden contributed 337, none failing, all getting starts with scores ranging from 26 to 113, so 123 would have been enough from Hayden to ensure an innings victory. Therefore, more than 250 of Hayden’s 380 runs in that innings can be considered completely meaningless.

Finishing off

None of the examples I have given was with any intention to disparage any particular player/s as even the very batsmen down the years have made their fair share of low value to completely meaningless runs.

I just wonder who would end up being who, if we did stats for players counting only their averages, fused together with speed of scoring, from runs scored only in genuinely meaningful situations.

Another rich source of meaningless runs is big innings played in high scoring draws in which neither side’s bowlers ever looked remotely likely to be able to take 20 opposition wickets. A certain 216 in Adelaide, or an unbeaten 203 in Perth would be perfect examples there.

Finally, it is also worth pointing out that bowlers can also take their fair share of meaningless wickets. If a side batting first is 5 for 500 mid-way through the second day of a test, and a declaration imminent, then a hattrick at that precise point in proceedings to finish with 6 for 146 makes no difference to the future outcome of the match.

Eventually developing into a genuinely fine bowler for Australia, Merv Hughes’s 13 for 217 against the West Indies in Perth back in 1988-89 was essentially a meaningless bowling performance.

His first innings haul of 5 for 130 was a stock, rather than strike performance, while his 8 for 87 in the second innings no doubt had some of the ‘benefits’ of the opposition endeavouring to push their scoring rate along to set up a declaration. McGrath’s 5 for 115 off 19 overs in the second innings of the third Test at Old Trafford in 2005 falls into the exact same category.

The third innings of a Test match, when the side who batted first is comfortably in front in the match, can often rather resemble the second half of the team batting first’s innings in a limited overs match. There are often cheap wickets to be snared which in actual fact do next to nothing to stifle the opposition’s surge towards victory.